Will try to sort out mess. Would any one like to volunteer for admin privileges?

Will try to sort out mess. Would any one like to volunteer for admin privileges?

Moderation release

As a temporary fix, until Lizzie returns, anyone who is being moderated and can’t comment is invited to leave a comment here and I will approve it, hoping that it will work as a fix for all commenters in all threads. Perhaps other thread authors could also check to see if they can do the same. I note that Lamont has approved my comment in his thread but this has not stopped my comments in other threads (including my own) ending up in moderation, so maybe it won’t, but you never know!

Added in edit:

Seems that author approval releases moderated comments in that thread only. As Lizzie is, I suspect, the only one with administrator permissions, we are stuck with the status quo.

Added in edit:

Seems it is worse than I thought. Author approval is apparently needed for each comment which is really impractical. Mark Frank has already suggested continuing on his blog but perhaps we could open an ad hoc wordpress blog with shared admin among volunteers and open authorship as this seems to operate well here. The level of abusive posting (apart from one notable exception) has been minimal and I think we should err on the side of open-ness. I will try and be alert to checking moderation.

Added in edit:

Just a thought. It could be democratic with shared admin (volunteers, please) and all members having author status by default as that seems to work well here. Keeping a wordpress format should make it easy to transfer active threads if need be.

Added in edit:

The moderation glitch appears to be fixed!

Skepticism and Atheism

Since this is the Skeptical Zone, I think it is appropriate to apply a little skepticism to atheism itself. How could anyone know if they were deceived by an evil demon into believing that God does not exist? Furthermore, if a person was trapped inside a matrix of evil lies and deception, is there anyway to escape and come to know the truth about God?

Certainly it is more likely that an atheist could be deceived by an evil spirit into not believing in God, than it is that all of us could be completely deceived about everything as Descartes proposed in his Meditations. Hence, this is an argument that the atheist should take seriously.

It should also be noted that the empirical sciences are of no help here because for the deception to be successful demons could not leave behind any testable evidence. If there was proof that demons existed, that would constitute strong evidence for the existence of God. So demons must remain hidden and work through nonphysical means.

So what would the deception look like? It would begin by asserting that all knowledge is acquired through the senses with the aid of the scientific method. Scientism, materialism, and naturalism provide the foundation for the deception. Knowledge of God is ruled out a priori.

Secondly, it would promote immorality as normal. Nothing keeps the mind from thinking about God any better than the vices of greed, lust, and pride.. A culture that promotes mindless consumerism, sexual promiscuity. and narcissism is perfect for this.

Finally it would mock religion in general and seek to place restrictions on religious speech and expression. Militant secularism and freedom from religion would be promoted as necessary for a healthy society. If a person never hears about God, then it is much less likely that they will think about God or believe in God.

Since all the elements of the deception are already in place, only a fool or a willing participant in the deception would refuse to investigate the unthinkable alternative. Maybe God actually exists.

Escape from the deception can come about in many ways. The first step is for the atheist to acknowledge the fact that he might be wrong and may have been deceived.

A second step is to consider the fact that everything that actually exists either came from something that actually exists or, is self-existent and exists eternally and immutably. The material things that science studies are all made of parts that can be put together to make something and broken apart and reformed to make something new. There is nothing in the material world that is eternal or unchangeable. The universe that we know is not eternal, it came from something else. That eternal something else that produced our universe cannot itself be composed of material parts for then it would not be self-existent or eternal. It must be immaterial. The immaterial, eternal, and immutable something else is what philosophers call God.

But what sort of being is immaterial and eternal? The one thing that we know of that is like that is our own minds or souls. Our minds are not bound by time. We can think of the past, the future, and the timeless. Our minds are not bound by space. Our bodies and our brains are in one place and our experience is limited to that place at that time. Our minds however, can be anywhere and we can think about anything that we choose to think about including abstract immaterial things that are not in any particular place or time. Most importantly we can choose to think about God.

Religion is the result of our thinking about God, and even though most of our thoughts about God may be wrong, it is possible that God is also thinking about us and wants us to know him. That is a possibility that is worth investigating. I believe that everyone who seriously seeks to undertake this investigation will eventually know the truth about God and be freed from all deception, but first you have to want the truth and nothing but the truth,

Admin: Everyone In Moderation

I don’t know if anyone will be able to see this. I posted a similar message on the Sandbox, but it didn’t appear.

If you are a logged in, registered user and click on the little speech bubble on the dashboard bar, you’ll get a list of comments awaiting moderation. You’ll also see this warning message:

Akismet has detected a problem. Some comments have not yet been checked for spam by Akismet. They have been temporarily held for moderation. Please check your Akismet configuration and contact your web host if problems persist.

This suggests that either Akismet is unreachable, possibly due to the recent storm, or that bit rot has set in and we need to summon Lizzie back somehow.

A specific instance of the problem of evil

This is The Skeptical Zone, so it’s only fitting that we turn our attention to topics other than ID from time to time.

The Richard Mourdock brouhaha provides a good opportunity for this. Mourdock, the Republican Senate candidate from the state of Indiana, is currently in the spotlight on my side of the Atlantic for a statement he made on Wednesday during a debate with his Democratic opponent:

You know, this is that issue that every candidate for federal or even state office faces. And I, too, certainly stand for life. I know there are some who disagree and I respect their point of view but I believe that life believes at conception. The only exception I have for – to have an abortion is in that case for the life of the mother. I just – I struggle with it myself for a long time but I came to realize that life is that gift from God, and I think even when life begins in that horrible situation of rape that it is something that God intended to happen. [emphasis mine]

Gpuccio’s challenge

29th Oct: I have offered a response to Gpuccio’s challenge below.

I think this is worth a new post.

Gpuccio has issued a challenge here and here. I have repeated the essential text below. Others may wish to try it and/or seek their own clarifications. Could be interesting. Something tells me that it is not going to end up in a clear cut result. But it may clarify the deeply confusing world of dFSCI.

Challenge:

Give me any number of strings of which you know for certain the origin. I will assess dFSCI in my way. If I give you a false positive, I lose. I will accept strings of a predetermined length (we can decide), so that at least the search space is fixed.

Conditions:

a) I would say binary strings of 500bits. Or language strings of 150 characters. Or decimal strings of 150 digits. Something like that. Even a mix of them would be fine.

No problem with that.

b) I will literally apply my procedure. If I cannot easily see any function for the string, I will not go on in the evaluation, and I will not infer design. If you, or any other, wants to submit strings whose function you know, you are free to tell me what the function is, and I will evaluate it thoroughly.

That’s OK. I will supply the function in each case. I note that when I tried to define function precisely you said that the function can be anything the observer wishes provided it is objectively defined, so, for example, “adds up to 1000” would be a function. So I don’t think that’s going to be an issue!

c) I will be cautious, and I will not infer design if I have doubts about any of the points in the procedure.

I am not happy with this. If the string meets the criteria for dFSCI you should be able to able to infer design. You can’t pick and choose when to apply it. At the very least you must prove that the string does not have dFSCI if you are going to avoid inferring design.

d) Ah, and please don’t submit strings outputted by an algorithm, unless you are ready to consider them as designed if the algorithm is more than 150 bits long. We should anyway agree, before we start, on which type of system and what time span we are testing.

I don’t understand this – a necessity system for generating digital strings can always be expressed as an algorithm e.g Fibonacci series. Otherwise it is just a copy of the string. Also it is not clear how to define how many bits long an algorithm is. Maybe it will suffice if I confine myself to algorithms that can be expressed mathematically in less than 20 symbols?

And anyway, I am afraid we have to wait next week for the test. My time is almost finished.

That’s OK. I need time to think anyway. But also I need to get your clarification on b,c and d.

On the Circularity of the Argument from Intelligent Design

There is a lot of debate in the comments to recent posts about whether the argument from ID is circular. I thought it would be worth calling this out as a separate item.

I plead that participants in this discussion (whether they comment here or on UD):

- make a real effort to stick to Lizzie’s principles (and her personal example) of respect for opposing viewpoints and politeness

- confine the discussion to this specific point (there is plenty of opportunity to discuss other points elsewhere and there is the sandbox)

What follows has been covered a thousand times. I simple repeat it in as rigorous a manner as I can to provide a basis for the ensuing discussion (if any!)

First, a couple of definitions.

A) For the purposes this discussion I will use “natural” to mean “has no element of design”. I do not mean to imply anything about materialism versus supernatural or such like. It is just an abbreviation for “not-designed”.

B) X is a “good explanation” for Y if and only if:

i) We have good reason to suppose X exists

ii) The probability of Y given X is reasonably high (say 0.1 or higher). There may of course be better explanations for Y where the probability is even higher.

Note that X may include design or be natural.

As I understand it, a common form of the ID argument is:

1) Identify some characteristic of outcomes such as CSI, FSCI or dFSCI. I will use dFSCI as an example in what follows but the point applies equally to the others.

2) Note that in all cases where an outcome has dFSCI, and a good explanation of the outcome is known, then the good explanation includes design and there is no good natural explanation.

3) Conclude there is a strong empirical relationship between dFSCI and design.

4) Note that living things include many examples of dFSCI.

5) Infer that there is a very strong case that living things are also designed.

This argument can be attacked from many angles but I want to concentrate on the circularity issue. The key point being that it is part of the definition of dFSCI (and the other measures) that there is no good natural explanation.

It follows that if a good natural explanation is identified then that outcome no longer has dFSCI. So it is true by definition that all outcomes with dFSCI fall into two categories:

- A good explanation has been identified and it is design

- No good explanation has yet been identified

Note that it was not necessary to do any empirical observation to prove this. It must always be the case from the definition of dFSCI that whenever a good explanation is identified it includes design.

I appreciate that as it stands this argument does not do justice to the ID position. If dFSCI was simply a synonym for “no good natural explanation” then the case for circularity would be obviously true. But is incorporates other features (as do its cousins CSI and FSCI). So for example dFSCI incorporates attributes such as digital, functional and not compressible – while CSI (in its most recent definition) includes the attribute compressible. So if we describe any of the measures as a set of features {F} plus the condition that if a good natural explanation is discovered then measure no longer applies – then it is possible to recast the ID argument this way:

“For all outcomes where {F} is observed then when a good explanation is identified it turns out to be designed and there is no good natural explanation. Many aspects of life have {F}. Therefore, there is good reason to suppose that design will be a good explanation and there will be no good natural explanation.”

The problem here is that while CSI, FSCI and dFSCI all agree on the “no good natural explanation” clause they differ widely on {F}. For Dembski’s CSI {F} is essentially equivalent to compressible (he refers to it as “simple” but defines “simple” mathematically in terms of easily compressible). While for FSCI {F} includes “has a function” and in some descriptions “not compressible”. dFSCI adds the additional property of being digital to FSCI.

By themselves both compressible and non-compressible phenomena clearly can have both natural and designed explanations. The structure of a crystal is highly compressible. CSI has no other relevant property and the case for circularity seems to be made at this point. But FSCI and dFSCI add the condition of being functional which perhaps makes all the difference. However, the word “functional” also introduces a risk of circularity. “Functional” usually means “has a purpose” which implies a purpose which implies a mind. In archaeology an artefact is functional if it can be seen to fulfil some past person’s purpose – even if that purpose is artistic. So if something has the attribute of being functional it follows by definition that a mind was involved. This means that by definition it is extremely likely, if not certain, that it was designed (of course, it is possible that it may have a good natural explanation and by coincidence also happen to fulfil someone’s purpose). To declare something to be functional is to declare it is engaged with a purpose and a mind – no empirical research is required to establish that a mind is involved with a functional thing in this sense.

But there remains a way of trying to steer FSCI and dFSCI away from circularity. When the term FSCI is applied to living things it appears a rather different meaning of “functional” is being used. There is no mind whose purpose is being fulfilled. It simply means the object (protein, gene or whatever) has a role in keeping the organism alive. Much as greenhouse gasses have a role in keeping the earth’s surface temperature at around 30 degrees. In this case of course “functional” does not imply the involvement of a mind. But then there are plenty of examples of functional phenomena in this sense which have good natural explanations.

The argument to circularity is more complicated than it may appear and deserves careful analysis rather than vitriol – but if studied in detail it is compelling.

A challenge to kairosfocus

A few weeks ago, commenter ‘kairosfocus’ (aka ‘KF’) posted a Pro-Darwinism Essay Challenge at Uncommon Descent. The challenge was for an ID critic to submit a 6000-word essay in defense of ‘Darwinism’, written to KF’s specifications. The essay would be posted at UD and a discussion would ensue.

The challenge generated no interest among the pro-evolution commenters here at TSZ, mainly because no one wanted to write an essay of KF’s specified length, on KF’s specified topic, in KF’s ridiculously specific format (and presumably double-spaced with a title page addressed to ‘Professor Kairosfocus’). We also had no interest in posting an essay at UD, a website that is notorious in the blogosphere for banning and censoring dissenters. Kairosfocus himself, in a ridiculous display of tinpot despotism, censored no less than 20 comments in the “Essay Challenge” thread itself!

(Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link, Link)

The commenter in question, ‘critical rationalist’, was banned from UD and has taken refuge here at TSZ, where open discussion is encouraged, dissent is welcome, comments are not censored, and only one commenter has ever been banned (for posting a photo of female genitalia).

Given the inhospitable environment at Uncommon Descent (from which I, like most of the ID critics at TSZ, have also been banned), I had (and have) no desire to submit an essay for publication at UD. However, I did respond to the spirit of KF’s challenge by writing a blog post here at TSZ that explains why unguided evolution, as a theory, is literally trillions of times better than Intelligent Design at explaining the evidence for common descent.

In his challenge, kairosfocus wrote:

It would be helpful if in that essay you would outline why alternatives such as design, are inferior on the evidence we face.

I have done exactly that, and so my challenge to kairosfocus is this: I have presented an argument showing that ID is vastly inferior to unguided evolution as an explanation of the evidence for common descent. Can you defend ID, or will you continue to claim your bogus daily victories despite being unable to rise to the challenge presented in my post?

Conflicting Definitions of “Specified” in ID

I see that in the unending TSZ and Jerad Thread Joe has written in response to R0bb

Try to compress the works of Shakespear- CSI. Try to compress any encyclopedia- CSI. Even Stephen C. Meyer says CSI is not amendable to compression.

A protein sequence is not compressable- CSI.

So please reference Dembski and I will find Meyer’s quote

To save Robb the effort. Using Specification: The Pattern That Signifies Intelligence by William Dembski which is his most recent publication on specification; turn to page 15 where he discusses the difference between two bit strings (ψR) and (R). (ψR) is the bit stream corresponding to the integers in binary (clearly easily compressible). (R) to quote Dembksi “cannot, so far as we can tell, be described any more simply than by repeating the sequence”. He then goes onto explain that (ψR) is an example of a specified string whereas (R) is not.

This conflict between Dembski’s definition of “specified” which he quite explicitly links to low Kolmogorov complexity (see pp 9-12) and others which have the reverse view appears to be a problem which most of the ID community don’t know about and the rest choose to ignore. I discussed this with Gpuccio a couple of years ago. He at least recognised the conflict and his response was that he didn’t care much what Dembski’s view is – which at least is honest.

Things That IDers Don’t Understand, Part 1 — Intelligent Design is not compatible with the evidence for common descent

Since the time of the Dover trial in 2005, I’ve made a hobby of debating Intelligent Design proponents on the Web, chiefly at the pro-ID website Uncommon Descent. During that time I’ve seen ID proponents make certain mistakes again and again. This is the first of a series of posts in which (as time permits) I’ll point out these common mistakes and the misconceptions that lie behind them.

I encourage IDers to read these posts and, if they disagree, to comment here at TSZ. Unfortunately, dissenters at Uncommon Descent are typically banned or have their comments censored, all for the ‘crime’ of criticizing ID or defending evolution effectively. Most commenters at TSZ, including our blog host Elizabeth Liddle and I, have been banned from UD. Far better to have the discussion here at TSZ where free and open debate is encouraged and comments are not censored.

The first misconception I’ll tackle is a big one: it’s the idea that the evidence for common descent is not a serious threat to ID. As it turns out, ID is not just threatened by the evidence for common descent — it’s literally trillions of times worse than unguided evolution at explaining the evidence. No exaggeration. If you’re skeptical, read on and I’ll explain.

The LCI and Bernoulli’s Principle of Insufficent Reason

(Just found I can post here – I hope it is not a mistake. This is a slightly shortened version of a piece which I have published on my blog. I am sorry it is so long but I struggle to make it any shorter. I am grateful for any comments. I will look at UD for comments as well – but not sure where they would appear.).

I have been rereading Bernoulli’s Principle of Insufficient Reason and Conservation of Information in Computer Search by William Dembski and Robert Marks. It is an important paper for the Intelligent Design movement as Dembski and Marks make liberal use of Bernouilli’s Principle of Insufficient Reason (BPoIR) in their papers on the Law of Conservation of Information (LCI). For Dembski and Marks BPoIR provides a way of determining the probability of an outcome given no prior knowledge. This is vital to the case for the LCI.

The point of Dembski and Marks paper is to address some fundamental criticisms of BPoIR. For example J M Keynes (along with with many others) pointed out that the BPoIR does not give a unique result. A well-known example is applying BPoIR to the specific volume of a given substance. If we know nothing about the specific volume then someone could argue using BPoIR that all specific volumes are equally likely. But equally someone could argue using BPoIR all specific densities are equally likely. However, as one is the reciprocal of the other, these two assumptions are incompatible. This is an example based on continuous measurements and Dembski and Marks refer to it in the paper. However, having referred to it, they do not address it. Instead they concentrate on the examples of discrete measurements where they offer a sort of response to Keynes’ objections. What they attempt to prove is a rather limited point about discrete cases such as a pack of cards or protein of a given length. It is hard to write their claim concisely – but I will give it a try.

Imagine you have a search space such as a normal pack of cards and a target such as finding a card which is a spade. Then it is possible to argue by BpoIR that, because all cards are equal, the probability of finding the target with one draw is 0.25. Dembski and Marks attempt to prove that in cases like this that if you decide to do a “some to many” mapping from this search space into another space then you have at best a 50% chance of creating a new search space where BPoIR gives a higher probability of finding a spade. A “some to many” mapping means some different way of viewing the pack of cards so that it is not necessary that all of them are considered and some of them may be considered more often than others. For example, you might take a handful out of the pack at random and then duplicate some of that handful a few times – and then select from what you have created.

There are two problems with this.

1) It does not address Keynes’ objection to BPoIR

2) The proof itself depends on an unjustified use of BPoIR.

But before that a comment on the concept of no prior knowledge.

The Concept of No Prior Knowledge

Dembski and Marks’ case is that BPoIR gives the probability of an outcome when we have no prior knowledge. They stress that this means no prior knowledge of any kind and that it is “easy to take for granted things we have no right to take for granted”. However, there are deep problems associated with this concept. The act of defining a search space and a target implies prior knowledge. Consider finding a spade in pack of cards. To apply BPoIR at minimum you need to know that a card can be one of four suits, that 25% of the cards have a suit of spades, and that the suit does not affect the chances of that card being selected. The last point is particularly important. BPoIR provides a rationale for claiming that the probability of two or more events are the same. But the events must differ in some respects (even if it is only a difference in when or where they happen) or they would be the same event. To apply BPoIR we have to know (or assume) that these differences are not relevant to the probability of the events happening. We must somehow judge that the suit of the card, the head or tails symbols on the coin, or the choice of DNA base pair is irrelevant to the chances of that card, coin toss or base pair being selected. This is prior knowledge.

In addition the more we try to dispense with assumptions and knowledge about an event then the more difficult it becomes to decide how to apply BPoIR. Another of Keynes’ examples is a bag of 100 black and white balls in an unknown ratio of black to white. Do we assume that all ratios of black to white are equally likely or do we assume that each individual ball is equally likely to be black or white? Either assumption is equally justified by BPoIR but they are incompatible. One results in a uniform probability distribution for the number of white balls from zero to 100; the other results in a binomial distribution which greatly favours roughly equal numbers of black and while balls.

Looking at the problems with the proof in Dembski and Marks’ paper.

The Proof does not Address Keynes’ objection to BPoIR

Even if the proof were valid then it does nothing to show that the assumption of BPoIR is correct. All it would show (if correct) was that if you do not use BPoIR then you have 50% or less chance of improving your chances of finding the target. The fact remains that there are many other assumptions you could make and some of them greatly increase your chances of finding the target. There is nothing in the proof that in anyway justifies assuming BPoIR or giving it any kind of privileged position.

But the problem is even deeper. Keynes’ point was not that there are alternatives to using BPoIR – that’s obvious. His point was that there are different incompatible ways of applying BPoIR. For example, just as with the example of black and white balls above, we might use BPoIR to deduce that all ratios of base pairs in a string of DNA are equally likely. Dembski and Marks do not address this at all. They point out the trap of taking things for granted but fall foul of it themselves.

The Proof Relies on an Unjustified Use of BPoIR

The proof is found in appendix A of the paper and this is the vital line:

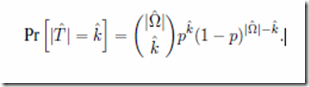

This is the probability that a new search space created from an old one will include k members which were part of the target in the original search space. The equation holds true if the new search space is created by selecting elements from old search space at random; for example, by picking a random number of cards at random from a pack. It uses BPoIR to justify the assumption that each unique way of picking cards is equally likely. This can be made clearer with an example.

Suppose the original search space comprises just the four DNA bases, one of which is the target. Call them x, y, z and t. Using BPoIR, Dembski and Marks would argue that all of them are equally likely and therefore the probability of finding t with a single search is 0.25. They then consider all the possible ways you might take a subset of that search space. This comprises:

Subsets with

no items

just one item: x,y,z and t

with two items: xy, xz, yz, tx, ty, tz

with three items: xyz, xyt, xzt, yzt

with four items: xyzt

A total of 16 subsets.

Their point is that if you assume each of these subsets is equally likely (so the probability of one of them being selected is 1/16) then 50% of them have a probability of finding t which is greater than or equal to probability in the original search space (i.e. 0.25). To be specific new search spaces where probability of finding t is greater than 0.25 are t, tx, ty, tz, xyt, xzt, yzt and xyzt. That is 8 out of 16 which is 50%.

But what is the justification for assuming each of these subsets are equally likely? Well it requires using BPoIR which the proof is meant to defend. And even if you grant the use of BPoIR Keynes’ concerns apply. There is more than one way to apply BPoIR and not all of them support Dembski and Marks’ proof. Suppose for example the subset was created by the following procedure:

- Start with one member selected at random as the subset

- Toss a dice,

- If it is two or less then stop and use current set as subset

- If it is a higher than two then add another member selected at random to the subset

- Continue tossing until dice throw is two or less or all four members in are in subset

This gives a completely different probability distribution.

The probability of:

single item subset (x,y,z, or t) = 0.33/4 = 0.083

double item subset (xy, xz, yz, tx, ty, or tz) = 0.66*0.33/6 = 0.037

triple item subset (xyz, xyt, xzt, or yzt) = 0.66*0.33*0.33/4 = 0.037

four item subset (xyzt) = 0.296

So the combined probability of the subsets where probability of selecting t is ≥ 0.25 (t, tx, ty, tz, xyt, xzt, yzt, xyzt) = 0.083+3*(0.037)+3*(0.037)+0.296 = 0.60 (to 2 dec places) which is bigger than 0.5 as calculated using Dembski and Marks assumptions. In fact using this method, the probability of getting a subset where the probability of selecting t ≥ 0.25 can be made as close to 1 as desired by increasing the probability of adding a member. All of these methods treat all four members of the set equally and are equally justified under BpoIR as Dembski and Marks assumption.

Conclusion

Dembski and Marks paper places great stress on BPoIR being the way to calculate probabilities when there is no prior knowledge. But their proof itself includes prior knowledge. It is doubtful whether it makes sense to eliminate all prior knowledge, but if you attempt to eliminate as much prior knowledge as possible, as Keynes does, then BPoIR proves to be an illusion. It does not give a unique result and some of the results are incompatible with their proof.

Gpuccio’s Theory of Intelligent Design

Gpuccio has made a series of comments at Uncommon Descent and I thought they could form the basis of an opening post. The comments following were copied and pasted from Gpuccio’s comments starting here

To onlooker and to all those who have followed thi discussion:

I will try to express again the procedure to evaluate dFSCI and infer design, referring specifically to Lizzies “experiment”. I will try also to clarify, while I do that, some side aspects that are probably not obvious to all.

Moreover, I will do that a step at a time, in as many posts as nevessary.

So, let’s start with Lizzie’s “experiment”:

Creating CSI with NS

Posted on March 14, 2012 by Elizabeth

Imagine a coin-tossing game. On each turn, players toss a fair coin 500 times. As they do so, they record all runs of heads, so that if they toss H T T H H H T H T T H H H H T T T, they will record: 1, 3, 1, 4, representing the number of heads in each run.At the end of each round, each player computes the product of their runs-of-heads. The person with the highest product wins.

In addition, there is a House jackpot. Any person whose product exceeds 1060 wins the House jackpot.

There are 2500 possible runs of coin-tosses. However, I’m not sure exactly how many of that vast number of possible series would give a product exceeding 1060. However, if some bright mathematician can work it out for me, we can work out whether a series whose product exceeds 1060 has CSI. My ballpark estimate says it has.

That means, clearly, that if we randomly generate many series of 500 coin-tosses, it is exceedingly unlikely, in the history of the universe, that we will get a product that exceeds 1060.

However, starting with a randomly generated population of, say 100 series, I propose to subject them to random point mutations and natural selection, whereby I will cull the 50 series with the lowest products, and produce “offspring”, with random point mutations from each of the survivors, and repeat this over many generations.

I’ve already reliably got to products exceeding 1058, but it’s

possible that I may have got stuck in a local maximum.

However, before I go further: would an ID proponent like to tell me whether, if I succeed in hitting the jackpot, I have satisfactorily refuted Dembski’s case? And would a mathematician like to check the jackpot?

I’ve done it in MatLab, and will post the script below. Sorry I don’t speak anything more geek-friendly than MatLab (well, a little Java, but MatLab is way easier for this) Continue reading

An Invitation to G Puccio

gpuccio addressed a comment to me at Uncommon Descent. Onlooker, a commenter now unable to post there,

(Added in edit 27/09/2012 – just to clarify, onlooker was banned from threads hosted by “kairosfocus” and can still post at Uncommon Descent in threads not authored by “kairosfocus”)

has expressed an interest in continuing a dialogue with gpuccio and petrushka comments:

By all means let’s have a gpuccio thread.

There are things I’d like to know about his position.

He claims that a non-material designer could insert changes into coding sequences. I’d like to know how that works. How does an entity having no matter or energy interact with matter and energy? Sounds to me like he is saying that A can sometimes equal not A.

He claims that variation is non stochastic and that adaptive adaptations are the result of algorithmic directed mutations. Is that in addition to intervention by non-material designers? How does that work?

What is the evidence that non-stochastic variation exists or that it is even necessary, given the Lenski experiment? Could he cite some evidence from the Lenski experiment that suggests directed mutations? Could he explain why gpuccio sees this and Lenski doesn’t?

It’s been a long time since gpuccio abandoned the discussion at the Mark Frank blog. I’d like to see that continued.

So I copy gpuccio’s comment here and add a few remarks hoping it may stimulate some interesting dialogue. Continue reading

Is ‘Design in Nature’ a Non-Starter?

A row is ready to erupt over two competing notions of ‘design in nature.’ One has been proposed under the auspices of being a natural-physical law. The other continues to clamour for public attention and respectability among natural-physical scientists, engineers and educators, but carries with it obvious religious overtones (Foundation for Thought and Ethics, Wedge Document and Dover trial 2005) and still has not achieved widespread scholarly support after almost 20 years of trying.

One the one hand is the Discovery Institute’s notion of ‘design in nature,’ which is repeated in various forms in the Intelligent Design movement. Here at TSZ many (the majority of?) people are against ID and ID proponents’ views of ‘design in nature.’ The author of this thread is likewise not an ID proponent, not an IDer. On the other hand is Duke University engineering and thermodynamics professor Adrian Bejan’s notion of ‘design in nature’ (Doubleday 2012, co-authored with journalism professor J. Peder Zane), which rejects Intelligent Design theory, but contends that ‘design’ is nevertheless a legitimate natural scientific concept. Apropos another recent thread here at TSZ, Bejan declares that his approach “solves one of the great riddles of science – design without a designer.”

A (repeated) challenge to Upright Biped

Upright Biped,

Before fleeing the discussion in July, you spent months here at TSZ discussing your “Semiotic Theory of ID”. During that time we all struggled with your vague prose, and you were repeatedly asked to clarify your argument and explain its connection to ID. I even summarized your argument no less than three times (!) and asked you to either confirm that my summary was accurate or to amend it accordingly. You failed to do so, and you also repeatedly refused to answer relevant, straightforward questions from other commenters here.

LCI or No LCI, Information Can Appear by Chance

(Preamble: I apologize in advance for cluttering TSZ with these three posts. There are very few people on either side of the debate that actually care about the details of this “conservation of information” stuff, but these posts make good on some claims I made at UD.)

To see that active information can easily be created by chance, even when the LCI holds, we’ll return to the Bertrand’s Box example. Recall that the LCI holds for this example, and all choices are strictly random. Recall further that choosing the GG box gives us 1 bit of active information since it doubles our chance of getting a gold coin. If we conduct 100 trials, we expect to get the GG box about 33 times, which means we expect 33 bits of active information to be generated by nothing but chance.

But before we say QED, we should note a potential objection, namely that we also expect to get SS about 33 times, and each such outcome gives us negative infinity bits of active information. So if we include the SS outcomes in our tally of active information, the total is negative infinity. Be that as it may, the fact remains that in 33 of the trials, 1 bit of information was generated. This fact is not rendered false by the outcomes of other trials, so those 33 trials produced 33 bits of information.

A Free Lunch of Active Info, with a Side of LCI Violations

(Preamble: I apologize in advance for cluttering TSZ with these three posts. There are very few people on either side of the debate that actually care about the details of this “conservation of information” stuff, but these posts make good on some claims I made at UD.)

Given a sample space Ω and a target T ⊆ Ω, Dembski defines the following information measures:

Endogenous information: IS ≡ -log2( P(T) )

Exogenous information: IΩ ≡ -log2( |T|/|Ω| )

Active information: I+ ≡ IΩ – IS = log2( P(T) / |T|/|Ω|)

Active information is supposed to indicate design, but in fact, the amount of active info attributed to a process depends on how we choose to mathematically model that process. We can get as much free active info as we want simply by making certain modeling choices.

Free Active Info via Individuation of Possibilities

Dembski is in the awkward position of having impugned his own information measures before he even invented them. From his book No Free Lunch:

This requires a measure of information that is independent of the procedure used to individuate the possibilities in a reference class. Otherwise the same possibility can be assigned different amounts of information depending on how the other possibilities in the reference class are individuated (thus making the information measure ill-defined).

He used to make this point often. But two of his new information measures, “endogenous information” and “active information”, depend on the procedure used to individuate the possible outcomes, and are therefore ill-defined according to Dembski’s earlier position.

To see how this fact allows arbitrarily high measures of active information, consider how we model the rolling of a six-sided die. We would typically define Ω as the set {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}. If the goal is to roll a number higher than one, then our target T is {2, 3, 4, 5, 6}. The amount of active information I+ is log2(P(T) / (|T|/|Ω|)) = log2((5/6) / (5/6)) = 0 bits.

But we could, instead, define Ω as {1, higher than 1}. In that case, I+ = log2((5/6) / (1/2)) = .7 bits. What we’re modeling hasn’t changed, but we’ve gained active information by making a different modeling choice.

Furthermore, borrowing an example from Dembski, we could distinguish getting a 1 with the die landing on the table from getting a 1 with the die landing on the floor. That is, Ω = { 1 on table, 1 on floor, higher than 1 }. Now I+ = log2((5/6) / (1/3)) = 1.3 bits. And we could keep changing how we individuate outcomes until we get as much active information as we desire.

This may seem like cheating. Maybe if we stipulate that Ω must always be defined the “right” way, then active information will be well-defined, right? But let’s look into another modeling choice that demonstrates that there is no “right” way to define Ω in the EIL framework.

Free Active Info via Inclusion of Possibilities

Again borrowing an example from Dembski, suppose that we know that there’s a buried treasure on the island of Bora Bora, but we have no idea where on the island it is, so all we can do is randomly choose a site to dig. If we want to model this search, it would be natural to define Ω as the set of all possible dig sites on Bora Bora. Our search, then, has zero active information, since it is no more likely to succeed than randomly selecting from Ω (because randomly selecting from Ω is exactly what we’re doing).

But is this the “right” definition of Ω? Dembski asks the question, “how did we know that of all places on earth where the treasure might be hidden, we needed to look on Bora Bora?” Maybe we should define Ω, as Dembski does, to include all of the dry land on earth. In this case, randomly choosing a site on Bora Bora is a high-active-information search, because it is far more likely to succeed than randomly choosing a site from Ω, i.e. the whole earth. Again, we have changed nothing about what is being modeled, but we have gained an enormous amount of active information simply by redefining Ω.

We could also take Dembski’s question further by asking, “how did we know that of all places in the universe, we needed to look on Bora Bora?” Now it seems that we’re being ridiculous. Surely we can take for granted the knowledge that the treasure is on the earth, right? No. Dembski is quite insistent that the zero-active-information baseline must involve no prior information whatsoever:

The “absence of any prior knowledge” required for uniformity conceptually parallels the difficulty of understanding the nothing that physics says existed before the Big Bang. It’s common to picture the universe before the Big Bang is a large black void empty space. No. This is a flawed image. Before the Big Bang there was nothing. A large black void empty space is something. So space must be purged from our visualization. Our next impulse is then, mistakenly, to say, “There was nothing. Then, all of a sudden…” No. That doesn’t work either. All of a sudden presupposes there was time and modern cosmology says that time in our universe was also created at the Big Bang. The concept of nothing must exclude conditions involving time and space. Nothing is conceptually difficult because the idea is so divorced from our experience and familiarity zones.

and further:

The “no prior knowledge” cited in Bernoulli’s PrOIR is all or nothing: we have prior knowledge about the search or we don’t. Active information on the other hand, measures the degree to which prior knowledge can contribute to the solution of a search problem.

To define a search with “no prior knowledge”, we must be careful not to constrain Ω. For example, if Ω consists of permutations, it must contain all permutations:

What search space, for instance, allows for all possible permutations? Most don’t. Yet, insofar as they don’t, it’s because they exhibit structures that constrain the permissible permutations. Such constraints, however, bespeak the addition of active information.

But even if we define Ω to include all permutations of a given ordered set, we’re still constraining Ω, as we’re excluding permutations of other ordered sets. We cannot define Ω without excluding something, so it is impossible to define a search without adding active information.

Active information is always measured relative to a baseline, and there is no baseline that we can call “absolute zero”. We therefore can attribute an arbitrarily large amount of active information to any search simply by choosing a baseline with a sufficiently large Ω.

Returning our six-sided die example, we can take the typical definition of Ω as {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6} and add, say, 7 and 8 to the set. Obviously our two additional outcomes each have a probability of zero, but that’s not a problem — probability distributions often include zero-probability elements. Inclusion of these zero-probability outcomes doesn’t change the mean, median, variance, etc. of the distribution, but it does change the amount of active info from 0 to log2((1/6) / (1/8)) = .4 bits (given a target of rolling, say, a one).

Free Violations of the LCI

Given a chain of two searches, the LCI says that the endogenous information of the first search is at least as large as the active information of the second. Since we can model the second search to have arbitrarily large active information, we can always model it such that its active information is larger than the first search’s endogenous information. Thus any chain of searches can be shown to violate the LCI. (We can also model the first search such that its endogenous information is arbitrarily large, so any chain of searches can also be shown to obey the LCI.)

The Law(?) of Conservation of Information

(Preamble: I apologize in advance for cluttering TSZ with these three posts. There are very few people on either side of the debate that actually care about the details of this “conservation of information” stuff, but these posts make good on some claims I made at UD.)

For the past three years Dembski has been promoting his Law of Conservation of Information (LCI), most recently here. The paper he most often promotes is this one, which begins as follows:

Laws of nature are universal in scope, hold with unfailing regularity, and receive support from a wide array of facts and observations. The Law of Conservation of Information (LCI) is such a law.

Dembski hasn’t proven that the LCI is universal, and in fact he claims that it can’t be proven, but he also claims that to date it has always been confirmed. He doesn’t say whether he as actually tried to find counterexamples, but the reality is that they are trivial to come up with. This post demonstrates one very simple counterexample.

Definitions

First we need to clarify Dembski’s terminology. In his LCI math, a search is described by a probability distribution over a sample space Ω. In other words, a search is nothing more than an Ω-valued random variable. Execution of the search consists of a single query, which is simply a realization of the random variable. The search is deemed successful if the realized outcome resides in target T ⊆ Ω. (We must be careful to not read teleology into the terms search, query, and target, despite the terms’ connotations. Obviously, Dembski’s framework must not presuppose teleology if it is to be used to detect design.)

If a search’s parameters depend on the outcome of a preceding search, then the preceding search is a search for a search. It’s this hierarchy of two searches that is the subject of the LCI, which we can state as follows.

Given a search S, we define:

- q as the probability of S succeeding

- p2 as the probability that S would succeed if it were a uniform distribution

- p1 as the probability that a uniformly distributed search-for-a-search would yield a search at least as good as S

The LCI says that p1 ≤ p2/q.

Counterexample

In thinking of a counterexample to the LCI, we should remember that this two-level search hierarchy is nothing more than a chain of two random variables. (Dembski’s search hierarchy is like a Markov chain, except that each transition is from one state space to another, rather than within the same state space.) One of the simplest examples of a chain of random variables is a one-dimensional random walk. Think of a system that periodically changes state, with each state transition represented by a shift to the left or to the right on an state diagram. If we know at a certain point in time that it is in one of, say, three states, namely n-1 or n or n+1, then after the next transition it will be in n-2, n-1, n, n+1, or n+2, as in the following diagram:

Assume that the system is always equally likely to shift left as to shift right, and let the “target” be defined as the center node n. If the state at time t is, say, n-1, then the probability of success q is 1/2. Of the three original states, two (namely n-1 and n+1) yield this probability of success, so p1 is 2/3. Finally, p2 is 1/5 since the target consists of only one of the final five states. The LCI says that p1 ≤ p2/q. Plugging in our numbers for this example, we get 2/3 ≤ (1/5)/(1/2), which is clearly false.

Of course, the LCI does hold under certain conditions. To show that the LCI to biological evolution, Dembski needs to show that his mathematical model of evolution meets those conditions. This model would necessarily include the higher-level search that gave rise to the evolutionary process. As will be shown in the next post, the good news for Dembski is that any process can be modeled such that it obeys the LCI. The bad news is that any process can also be modeled such that it violates the LCI.

Dembski: “Conservation of Information Made Simple”

At Uncommon Descent, Bill Dembski has announced the posting of a new article, Conservation of Information Made Simple, at Evolution News and Views. Comments are disabled at ENV, and free and open discussion is not permitted at UD. I’ve therefore created this thread to give critics of ID a place to discuss the article free of censorship.

Apologies to Kairosfocus and Petrushka

It seems I have given great offence to the commenter, Kairosfocus, at Uncommon Descent with my comment:

I see Kairosfocus is reading comments here.

I can’t tell for sure but is KF owning up to or denying banning mphillips? In case he finds time to read more…

Come on over, KF and, so long as you don’t link to porn and can be succinct enough not to overload the software, you will be very welcome, I’m sure!

I would like first to point out to Kairosfocus that he is mistakenly attributing the comment to Petrushka, a fellow commenter here and elsewhere. I would like to say sorry to Petrushka too for apparently initiating the misdirected criticism she has received.

I am sorry it wasn’t as obvious to Kairosfocus as it was to others that my invitation to post here contained a light-hearted reference to the only (as far as I am aware) IP ban ever meted out at The Skeptical Zone, received by Joe Gallien in response to his linking a graphically pornographic image here. I hope that clears up any misunderstanding and if Kairosfocus changes his mind about commenting here, I am sure he will find the moderation rules will be adhered to fairly.