Questions about the existence and attributes of God form the subject matter of natural theology, which seeks to gain knowledge of the divine by relying on reason and experience of the world. Arguments in natural theology rely largely on intuitions and inferences that seem natural to us, occurring spontaneously — at the sight of a beautiful landscape, perhaps, or in wonderment at the complexity of the cosmos — even to a non-philosopher.

Category Archives: Mind and brain

Alzheimer’s and Evolution

I have to say, while the UD “newsdesk” is terrible source for comment on scientific news, the links themselves are often interesting. Today, the UD “newsdesk” reports on a pretty interesting study, reported in Nature, here, and a preprint of which seems to be open access here

It’s been apparent for a while from Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) that “risk” alleles for various mental disorders, despite being statistically significant, have extremely small effect sizes. In other words, while the studies show that many mental disorders are indeed associated with specific alleles (and we already know that many are highly heritable, including schizophrenia, ADHD and Alzheimer’s), there aren’t just a few rogue alleles of large effect (well, there are, but they are far rarer than these disorders), but instead, a whole cocktail of alleles with very slightly raised Odds Ratios for certain disorders (and some are shared between multiple disorders). This means that the vast majority of people carrying these “risk alleles” are perfectly fine. That would help explain why they have not been weeded out by selection.

Amie Thomasson on nonreductive physicalism

Let’s discuss Amie Thomasson’s paper A Nonreductivist Solution to Mental Causation. I’ll save my thoughts for the comment thread.

Michael Graziano: Are We Really Conscious?

He raises the question in the New York Times Sunday Review:

I believe a major change in our perspective on consciousness may be necessary, a shift from a credulous and egocentric viewpoint to a skeptical and slightly disconcerting one: namely, that we don’t actually have inner feelings in the way most of us think we do…

How does the brain go beyond processing information to become subjectively aware of information? The answer is: It doesn’t. The brain has arrived at a conclusion that is not correct. When we introspect and seem to find that ghostly thing — awareness, consciousness, the way green looks or pain feels — our cognitive machinery is accessing internal models and those models are providing information that is wrong…

Some questions about music in the head

1.How many of you have a song or some other piece of music “playing” in your head, right now?

2. During roughly what percentage of your waking time do you have “mental music” playing (that is, when you’re not listening to an external source of music)?

3. How much voluntary control do you have over the music playing in your head? If a song you don’t like starts to “play”, are you able to replace it with something you like better, or do you get stuck with “earworms” – songs that you can’t get rid of despite trying?

Stuck between a rock and an immaterial place

Kairosfocus has a new OP at UD entitled Putting the mind back on the table for discussion. His argument begins thus:

Starting with the principle that rocks have no dreams:

Reciprocating Bill points out that since KF denies physicalism, he has no principled basis for denying the consciousness of rocks:

If the physical states exhibited by brains, but absent in rocks, don’t account for human dreams (contemplation, etc.) then you’ve no basis for claiming rocks are devoid of dreams – at least not on the basis of the physical states present in brains and absent in rocks. Given that, on what basis do you claim that rocks don’t dream?

Needless to say, KF is squirming to avoid the question.

I’ve got popcorn in the microwave. Pull up a chair.

Language: evolution or design?

Humans are both very like and very different from other species we find on Earth. At the sub-cellular and biochemical level, the similarities, the almost universality of the DNA code and its property of self-duplication and storage of genetic information is breathtaking. On the other hand, no other species has succeeded in the scope and breadth of it’s colonization of this planet. Much of the “success” in growing a population that now exceeds seven billion individuals can be attributed to our being a social species. Sociability and its evolutionary roots have been well studied. However there does seem to be something missing. The rapid runaway expansion of human culture and the extraordinary flowering of human art, which might be attributed in turn to the literal expansion of the human brain seem to require further explanation. Continue reading

A Critique of Naturalism

The ‘traditional’ objections to a wholly naturalistic metaphysics, within the modern Western philosophical tradition, involve the vexed notions of freedom and consciousness. But there is, I think, a much deeper and more interesting line of criticism to naturalism, and that involves the notion of intentionality and its closely correlated notion of normativity.

What is involved in my belief that I’m drinking a beer as I type this? Well, my belief is about something — namely, the beer that I’m drinking. But what does this “aboutness” consist of? It requires, among other things, a commitment that I have undertaken — that I am prepared to respond to the appropriate sorts of challenges and criticisms of my belief. I’m willing to play the game of giving and asking for reasons, and my willingness to be so treated is central to how others regard me as their epistemic peer. But there doesn’t seem to be any way that the reason-giving game can be explained entirely in terms of the neurophysiological story of what’s going on inside my cranium. That neurophysiological story is a story of is the case, and the reason-giving story is essentially a normative story — of what ought to be the case.

And if Hume is right — as he certainly seems to be! — in saying that one cannot derive an ought-statement from an is-statement,and if naturalism is an entirely descriptive/explanatory story that has no room for norms, then in light of the central role that norms play in human life (including their role in belief, desire, perception, and action), it is reasonable to conclude that naturalism cannot be right.

(Of course, it does not follow from this that any version of theism or ‘supernaturalism’ must be right, either.)

Sean Carroll and Steven Novella debate life after death with Eben Alexander and Raymond Moody

The shortcomings of the ‘brain as radio receiver’ model

Folks who believe in an immaterial soul (also known as ‘substance dualists’) face a daunting challenge. Why, if our mental and emotional functions are carried out by the immaterial soul, are they so completely affected by changes to the physical brain?

An astonishingly lame argument from Alvin Plantinga

Alvin Plantinga is widely regarded as one of the world’s leading Christian philosophers. Watch the video below and ask yourself, WTF?

So as not to spoil your fun, I’ll refrain from offering my take on the argument until readers have had a chance to comment.

Our prejudices: Implicit associations

We all have biases that we should try to be aware of. Our implicit prejudices may be at odds with our explicit attitudes. One problem when discussing issues such as racism and sexism especially is that surprisingly many people seem to think that such things have been largely dealt with in the 20th Century and are now of minimal importance.

https://implicit.harvard.edu has several tests designed to measure our implicit biases. As with any scientific test, there could be issues with methodology etc and, in addition to discussion of implicit biases (e.g. the psychology of them, how they affect our skepticism), that also seems an appropriate topic for discussion here.

What Are Concepts?

There’s a nice little discussion going on at Uncommon Descent (see here) about whether concepts are consistent with naturalism (broadly conceived). Here I want to say a bit about what theories of concepts seem to me to be most promising, and to what extent (if any) they are compatible with naturalism (broadly conceived).

The dominant position in philosophy of language treats concepts as representations: I have a concept of *dog* insofar as I am able to correctly represent all dogs as dogs. It is crucial that concepts have the right kind of generality — that I am able to classify all particular dogs as exemplifying the same general property — in order to properly credit me with having the concept. (If I only applied the term “dog” to my dog, it would be right to say that I don’t really have the concept *dog*.)

On the representationalist paradigm, rational thought has a bottom-up structure: terms are applied to particulars, terms are combined to form judgments about particulars, and judgments are combined to form arguments, explanations, and other forms of reasoning.

Is God a brain in a vat?

From a comment I made last year at UD:

It’s impossible to verify the reliability of a cognitive system from the inside. Why? Because you have to use the cognitive system itself in order to verify its reliability.

If the system isn’t reliable, you might mistakenly conclude that it is!

This even applies to God himself. From the inside, God may think that he’s omniscient and omnipotent. He seems to know everything about reality, and he seems to be able to do anything that is logically possible. But how can he know these things with absolute certainty?

What if there is a higher-level God, or demon, who is deceiving him into thinking that he’s the master of the universe when he really isn’t? How, for that matter, can God be sure that he isn’t a brain in a vat?

He can’t. Defining him as omniscient doesn’t help. Like everyone else, he can only try to determine, from the inside, whether his cognitive apparatus is reliable. He can never be absolutely sure that he isn’t being fooled, or fooling himself.

Facts as human artifacts

BruceS suggested that I start a thread on my ideas about human cognition. I’m not sure how this will work out, but let’s try. And, I’ll note that I have an earlier thread that is vaguely related.

The title of this thread is one of my non-traditional ideas about cognition. And if I am correct, as I believe I am, then our relation to the world is very different from what is usually assumed.

The traditional view is that we pick up facts, and most of cognition has to do with reasoning about these facts. If I am correct, then there are no facts to pick up. So the core of cognition has to be engaged in solving the problem of having useful facts about the world.

Chicago Coordinates

I’ll start with a simple example. I typed “Chicago Coordinates” into Google, and the top of the page returned showed:

41.8819° N, 87.6278° W

That’s an example of what we would take to be a fact. Yet, without the activity of humans, it could not exist as a fact. In order for that to be a fact, we had to first invent a geographic coordinate system (roughly, the latitude/longitude system). And that coordinate system in turn depends on some human conventions. For example, the meridian through Greenwich was established as the origin for the longitudes.

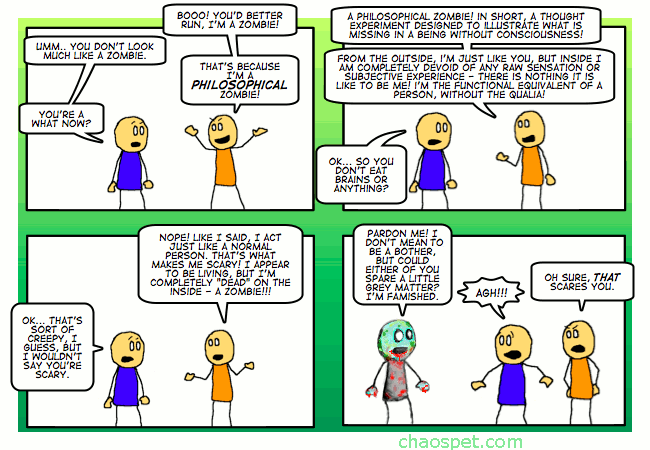

“The Quale is the Difference”

Barry has graciously posted a counter-rebuttal at UD to my Zombie Fred post rebutting his own original zombie post at UD. (This debate-at-a-distance procedure isn’t a bad way to proceed, actually! Although as always, he is welcome to come over here in person if he would like.)

Zombie Fred

A neat zombie post from Barry Arrington (thanks, Barry! I do appreciate, and this is without snark, the succinctness and articulacy of your posts – they encapsulate your ideas extremely cogently, and thus make it much easier for me to see just how and why I disagree with you!)

The Three Acts of the Mind

How does mind move matter? To me, the question appears rather uninteresting. A simple collision is all that’s required to move matter.

How does the mind act at all, and what are the acts of the mind?

1. Simple apprehension

2. Judging

3. Reasoning

Alan Fox asserts that knowledge consists of apprehension.

Elizabeth Liddle claims that she agrees with Alan, but fails to incorporate her belief in the construction of mental models with Alan’s reductionist denial of the incorporation of mental models.

Does knowledge consist only of what can be sensed, as Alan Fox claims?

Or does knowledge consist of only what can be sensed and modeled, as Elizabeth claims?

Can science resolve the question of what can be considered knowledge, as Alan Fox claims?

How does mind move matter

One big problem, as I mentioned here, and elsewhere, with ID as a hypothesis is that it is predicated on the idea that mind is “immaterial” (or at least “non-materialistic”) yet can have an effect on matter. That’s the basis of Beauregard and O’Leary’s book “The Spiritual Brain”, as well as of a number of theories of consciousness and/or free will. And, if true, it makes some kind of sense of ID – if by “intelligence” we mean a “mind” (as opposed to, say, an algorithm, and we have many that can produce output from input that is far beyond anything human beings can manage unaided, and can in some sense be said to be “intelligence”), we are also implicitly talking about something that intends an outcome. Which is why I’ve always thought that ID would make more sense if the I stood for “Intentional” rather than “Intelligence”, but for some reason Dembski thinks that “intention”, together with ethics, aesthetics and the identity of the designer, “are not questions of science”.

I would argue that intention is most definitely a “question of science”, but that’s not my primary point here.

Qualia

Denyse O’Leary writes (ironically in a UD post that has attracted 500+ comments, in none of which is the word mentioned, or the topic touched):

Materialist neuroscience has a hard time with qualia because they are not easily reducible to a simple, nonconscious explanation.