During the past few days, Dr. Brian Miller (whose Ph.D. is in physics) has written a series of articles on the origin of life over at Evolution News and Views:

Thermodynamics of the Origin of Life (June 19, 2017)

The Origin of Life, Self-Organization, and Information (June 20, 2017)

Free Energy and the Origin of Life: Natural Engines to the Rescue (June 22, 2017)

Origin of Life and Information — Some Common Myths (June 26, 2017)

Dr. Miller’s aim is to convince his readers that intelligent agency was required to coordinate the steps leading to the origin of life. I think his conclusion may very well be correct, but that doesn’t make his arguments correct. In this post, I plan to subject Dr. Miller’s arguments to scientific scrutiny, in order to determine whether Dr. Miller has made a strong case for Intelligent Design.

While I commend Dr. Miller for his indefatigability, I find it disappointing that his articles recycle several Intelligent Design canards which have been refuted on previous occasions. Dr. Miller also seems to be unaware of recently published online articles which address some of his concerns.

1. Thermodynamics of the Origin of Life

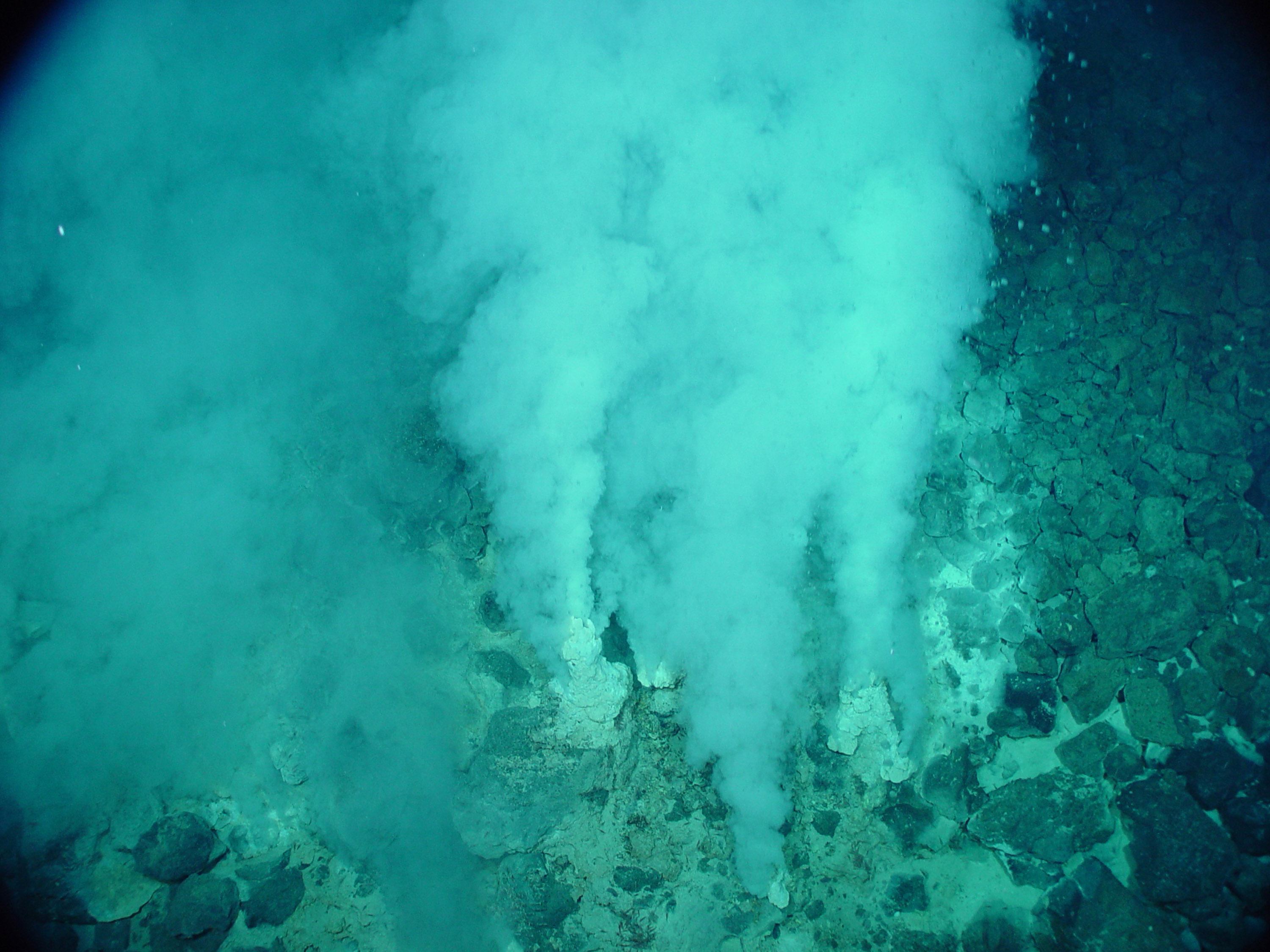

White smokers emitting liquid carbon dioxide at the Champagne vent, Northwest Eifuku volcano, Marianas Trench Marine National Monument. Image courtesy of US NOAA and Wikipedia.

In his first article, Thermodynamics of the Origin of Life, Dr. Miller critiques the popular scientific view that life originated in a “system strongly driven away from equilibrium” (or more technically, a non-equilibrium dissipative system), such as “a pond subjected to intense sunlight or the bottom of the ocean near a hydrothermal vent flooding its surroundings with superheated water and high-energy chemicals.” Dr. Miller argues that this view is fatally flawed, on three counts:

First, no system could be maintained far from equilibrium for more than a limited amount of time. The sun is only out during the day, and superheated water at the bottom of the ocean would eventually migrate away from any hydrothermal vents. Any progress made toward forming a cell would be lost as the system reverted toward equilibrium (lower free energy) and thus away from any state approaching life. Second, the input of raw solar, thermal, or other forms of energy actually increase the entropy of the system, thus moving it in the wrong direction. For instance, the ultraviolet light from the sun or heat from hydrothermal vents would less easily form the complex chemical structures needed for life than break them apart. Finally, in non-equilibrium systems the differences in temperature, concentrations, and other variables act as thermodynamic forces which drive heat transfer, diffusion, and other thermodynamic flows. These flows create microscopic sources of entropy production, again moving the system away from any reduced-entropy state associated with life. In short, the processes occurring in non-equilibrium systems, as in their near-equilibrium counterparts, generally do the opposite of what is actually needed.

Unfortunately for Dr. Miller, none of the foregoing objections is particularly powerful, and most of them are out-of-date. I would also like to note for the record that while the hypothesis that life originated near a hydrothermal vent remains popular among origin-of-life theorists, the notion that this vent was located at “the bottom of the ocean” is now widely rejected. Miller appears to be unaware of this. In fact, as far back as 1988, American chemist Stanley Miller, who became famous when he carried out the Miller-Urey experiment in 1952, had pointed out that long-chain molecules such as RNA and proteins cannot form in water without enzymes to help them. Additionally, leading origin-of-life researchers such as Dr. John Sutherland (of the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, UK) and Dr. Jack Szostak (of Harvard Medical School) have discovered that many of the chemical reactions leading to life depend heavily on the presence of ultraviolet light, which only comes from the sun. This rules out a deep-sea vent scenario. That’s old news. Let us now turn to Dr. Miller’s three objections to the idea of life originating in a non-equilibrium dissipative system.

(a) Could a non-equilibrium be kept away from equilibrium?

Miller’s first objection is that non-equilibrium systems can’t be maintained for very long, which would mean that life would never have had time to form in the first place. However, a recent BBC article by Michael Marshall, titled, The secret of how life on Earth began (October 31, 2016), describes a scenario, proposed by origin-of-life researcher John Sutherland, which would evade the force of this objection. Life, Sutherland believes, may have formed very rapidly:

Sutherland has set out to find a “Goldilocks chemistry”: one that is not so messy that it becomes useless, but also not so simple that it is limited in what it can do. Get the mixture just complicated enough and all the components of life might form at once, then come together.

In other words, four billion years ago there was a pond on the Earth. It sat there for years until the mix of chemicals was just right. Then, perhaps within minutes, the first cell came into existence.

“But how, and where?” readers might ask. One plausible site for this event, put forward by origin-of-life expert Armen Mulkidjanian, is the geothermal ponds found near active volcanoes. Because these ponds would be continually receiving heat from volcanoes, they would not return to equilibrium at night, as Dr. Miller supposes.

Another likely location for the formation of life, proposed by John Sutherland, is a meteorite impact zone. This scenario also circumvents Miller’s first objection, as large-scale meteorite impacts would have melted the Earth’s crust, leading to geothermal activity and a continual supply of hot water. The primordial Earth was pounded by meteorites on a regular basis, and large impacts could have created volcanic ponds where life might have formed:

Sutherland imagines small rivers and streams trickling down the slopes of an impact crater, leaching cyanide-based chemicals from the rocks while ultraviolet radiation pours down from above. Each stream would have a slightly different mix of chemicals, so different reactions would happen and a whole host of organic chemicals would be produced.

Finally the streams would flow into a volcanic pond at the bottom of the crater. It could have been in a pond like this that all the pieces came together and the first protocells formed.

(b) Would an input of energy increase entropy?

What about Miller’s second objection, that the input of energy would increase the entropy of the system, thus making it harder for the complex chemical structures needed for life to form, in the first place?

Here, once again, recent work in the field seems to be pointing to a diametrically opposite conclusion. A recent editorial on non-equilibrium dissipative systems (Nature Nanotechnology 10, 909 (2015)) discusses the pioneering work of Dr. Jeremy England, who maintains that the dissipation of heat in these systems can lead to the self-organization of complex systems, including cells:

The theoretical concepts presented are not new — they have been rigorously reported before in specialized physics literature — but, as England explains, recently there has been a number of theoretical advances that, taken together, might lead towards a more complete understanding of non-equilibrium phenomena. More specifically, the meaning of irreversibility in terms of the amount of work being dissipated as heat as a system moves on a particular trajectory between two states. It turns out, this principle is relatively general, and can be used to explain the self-organization of complex systems such as that observed in nanoscale assemblies, or even in cells.

Dr. England, who is by the way an Orthodox Jew, has derived a generalization of the second law of thermodynamics that holds for systems of particles that are strongly driven by an external energy source, and that can dump heat into a surrounding bath. All living things meet these two criteria. Dr. England has shown that over the course of time, the more likely evolutionary outcomes will tend to be the ones that absorbed and dissipated more energy from the environment’s external energy sources, on the way to getting there. In his own words: “This means clumps of atoms surrounded by a bath at some temperature, like the atmosphere or the ocean, should tend over time to arrange themselves to resonate better and better with the sources of mechanical, electromagnetic or chemical work in their environments.”

There are two mechanisms by which a system might dissipate an increasing amount of energy over time. One such mechanism is self-replication; the other, greater structural self-organization. Natalie Wolchover handily summarizes Dr. England’s reasoning in an article in Quanta magazine, titled, A New Physics Theory of Life (January 22, 2014):

Self-replication (or reproduction, in biological terms), the process that drives the evolution of life on Earth, is one such mechanism by which a system might dissipate an increasing amount of energy over time. As England put it, “A great way of dissipating more is to make more copies of yourself.” In a September paper in the Journal of Chemical Physics, he reported the theoretical minimum amount of dissipation that can occur during the self-replication of RNA molecules and bacterial cells, and showed that it is very close to the actual amounts these systems dissipate when replicating. He also showed that RNA, the nucleic acid that many scientists believe served as the precursor to DNA-based life, is a particularly cheap building material. Once RNA arose, he argues, its “Darwinian takeover” was perhaps not surprising…

Besides self-replication, greater structural organization is another means by which strongly driven systems ramp up their ability to dissipate energy. A plant, for example, is much better at capturing and routing solar energy through itself than an unstructured heap of carbon atoms. Thus, England argues that under certain conditions, matter will spontaneously self-organize. This tendency could account for the internal order of living things and of many inanimate structures as well. “Snowflakes, sand dunes and turbulent vortices all have in common that they are strikingly patterned structures that emerge in many-particle systems driven by some dissipative process,” he said.

Dr. Jeremy England is an MIT physicist. Dr. Miller is also a physicist. I find it puzzling (and more than a little amusing) that Dr. Miller believes that increasing the entropy of a non-equilibrium dissipative system will inhibit the formation of complex chemical structures required for life to exist, whereas Dr. England believes the exact opposite!

(c) Would local variations within non-equilibrium dissipative systems prevent life from forming?

What of Dr. Miller’s third objection, that differences in temperature, concentrations, and other variables arising within a non-equilibrium dissipative system will generate entropy on a microscopic scale, creating disturbances which move the system away from a reduced-entropy state, which is required for life to exist? Dr. David Ruelle, author of a recent Arxiv paper titled, The Origin of Life seen from the point of view of non-equilibrium statistical mechanics (January 29, 2017), appears to hold a contrary view. In his paper, Dr. Ruelle refrains from proposing a specific scenario for the origin of life; rather, his aim, as he puts it, is to describe “a few plausible steps leading to more and more complex states of pre-metabolic systems so that something like life may naturally arise.” Building on the work of Dr. Jeremy England and other authors in the field, Dr. Ruelle contends that “organized metabolism and replication of information” can spontaneously arise from “a liquid bath (water containing various solutes) interacting with some pre-metabolic systems,” where the pre-metabolic systems are defined as “chemical associations which may be carried by particles floating in the liquid, or contained in cracks of a solid boundary of the liquid.” At the end of his paper, Dr. Ruelle discusses what he calls pre-biological systems, emphasizing their ability to remain stable in the face of minor fluctuations, and describing how their complexity can increase over time:

In brief, a pre-biological state is generally indecomposable. This means in particular that the fluctuations in its composition are not large. The prebiological state is also stable under small perturbations, except when those lead to a new metabolic pathway, changing the nature of the state.

We see thus a pre-biological system as a set of components undergoing an organized set of chemical reactions using a limited amount of nutrients in the surrounding fluid. The complexity of the pre-biological system increases as the amount of available nutrients decreases. The system can sustain a limited amount of disturbance. An excessive level of disturbance destroys the organized set of reactions on which the system is based: it dies.

Evidently Dr. Ruelle believes that non-equilibrium dissipative systems are resilient to minor fluctuations, and even capable of undergoing an increase in complexity, whereas Dr. Miller maintains that these fluctuations would prevent the formation of life.

If Dr. Miller believes that Dr. Ruelle is wrong, perhaps he would care to explain why.

2. The Origin of Life, Self-Organization, and Information

The three main structures phospholipids form spontaneously in solution: the liposome (a closed bilayer), the micelle and the bilayer. Image courtesy of Lady of Hats and Wikipedia.

I turn now to Dr. Miller’s second article, The Origin of Life, Self-Organization, and Information. In this article, Dr. Miller argues that there are profound differences between self-organizational order and the cellular order found in living organisms. Non-equilibrium dissipative systems might be able to generate the former kind of order, but not the latter.

The main reason for the differences between self-organizational and cellular order is that the driving tendencies in non-equilibrium systems move in the opposite direction to what is needed for both the origin and maintenance of life. First, all realistic experiments on the genesis of life’s building blocks produce most of the needed molecules in very small concentrations, if at all. And, they are mixed together with contaminants, which would hinder the next stages of cell formation. Nature would have needed to spontaneously concentrate and purify life’s precursors…

Concentration of some of life’s precursors could have taken place in an evaporating pool, but the contamination problem would then become much worse since precursors would be greatly outnumbered by contaminants. Moreover, the next stages of forming a cell would require the concentrated chemicals to dissolve back into some larger body of water, since different precursors would have had to form in different locations with starkly different initial conditions…

In addition, many of life’s building blocks come in both right and left-handed versions, which are mirror opposites. Both forms are produced in all realistic experiments in equal proportions, but life can only use one of them: in today’s life, left-handed amino acids and right-handed sugars. The origin of life would have required one form to become increasingly dominant, but nature would drive a mixture of the two forms toward equal percentages, the opposite direction.

(a) Why origin-of-life theorists are no longer obsessed with purity

Dr. Miller’s contention that contaminants would hinder the formation of living organisms has been abandoned by modern origin-of-life researchers, as BBC journalist Michael Marshall reports in his 2016 article, The secret of how life on Earth began. After describing how researcher John Sutherland was able to successfully assemble a nucleotide using a messy solution that contained a contaminant (phosphate) at the outset, leading Sutherland to hypothesize that for life to originate, there has to be “an optimum level of mess” (neither too much nor too little), Marshall goes on to discuss the pioneering experiments of another origin-of-life researcher, Jack Szostak, whose work has led him to espouse the same conclusion as Sutherland:

Szostak now suspects that most attempts to make the molecules of life, and to assemble them into living cells, have failed for the same reason: the experiments were too clean.

The scientists used the handful of chemicals they were interested in, and left out all the other ones that were probably present on the early Earth. But Sutherland’s work shows that, by adding a few more chemicals to the mix, more complex phenomena can be created.

Szostak experienced this for himself in 2005, when he was trying to get his protocells to host an RNA enzyme. The enzyme needed magnesium, which destroyed the protocells’ membranes.

The solution was a surprising one. Instead of making the vesicles out of one pure fatty acid, they made them from a mixture of two. These new, impure vesicles could cope with the magnesium – and that meant they could play host to working RNA enzymes.

What’s more, Szostak says the first genes might also have embraced messiness.

Modern organisms use pure DNA to carry their genes, but pure DNA probably did not exist at first. There would have been a mixture of RNA nucleotides and DNA nucleotides.

In 2012 Szostak showed that such a mixture could assemble into “mosaic” molecules that looked and behaved pretty much like pure RNA. These jumbled RNA/DNA chains could even fold up neatly.

This suggested that it did not matter if the first organisms could not make pure RNA, or pure DNA…

(b) Getting it together: how the first cell may have formed

Dr. Miller also argues that even if the components of life were able to form in separate little pools, the problem of how they came to be integrated into a living cell would still remain. In recent years, Dr. John Sutherland has done some serious work on this problem. Sutherland describes his own preferred origin-of-life scenario in considerable detail in a paper titled, The Origin of Life — Out of the Blue (Angewandte Chemie, International Edition, 2016, 55, 104 – 121.

Several years ago, we realised that … polarisation of the field was severely hindering progress, and we planned a more holistic approach. We set out to use experimental chemistry to address two questions, the previously assumed answers to which had led to the polarisation of the field: “Are completely different chemistries needed to make the various subsystems?” [and] “Would these chemistries be compatible with each other?”…

With twelve amino acids, two ribonucleotides and the hydrophilic moiety of lipids synthesised by common chemistry, we feel that we have gone a good way to answering the first of the questions we posed at the outset. “Are completely different chemistries needed to make the various subsystems?” — we would argue no! We need to find ways of making the purine ribonucleotides, but hydrogen cyanide 1 is already strongly implicated as a starting material. We also need to find ways of making the hydrophobic chains of lipids, and maybe a few other amino acids, but there is hope in reductive homologation chemistry or what we have called “cyanosulfidic protometabolism.” …

The answer to the second question — “Would these chemistries be compatible with each other?” — is a bit more vague (thus far). The chemistries associated with the different subsystems are variations on a theme, but to operate most efficiently some sort of separation would seem to be needed. Because a late stage of our scenario has small streams or rivulets flowing over ground sequentially leaching salts and other compounds as they are encountered (Figure 17), it provides a very simple way in which variants of the chemistry could play out separately before all the products became mixed.

Separate streams might encounter salts and other compounds in different orders and be exposed to solar radiation differently. Furthermore streams might dry out and the residues become heated through geothermal activity before fresh inflow of water. If streams with different flow chemistry histories then merged, convergent synthesis might occur at the confluence and downstream thereof, or products might simply mix. It would be most plausible if only a few streams were necessary for the various strands of the chemistry to operate efficiently before merger. Our current working model divides the reaction network up such that the following groups of building blocks would be made separately: ribonucleotides; alanine, threonine, serine and glycine; glycerol phosphates, valine and leucine; aspartic acid, asparagine, glutamic acid and glutamine; and arginine and proline. Because the homologation of all intermediates uses hydrogen cyanide (1), products of reductive homologation of (1) — especially glycine — could be omnipresent.

Since then, Sutherland has written another paper, titled, Opinion: Studies on the origin of life — the end of the beginning (Nature Reviews Chemistry 1, article number: 0012 (2017), doi:10.1038/s41570-016-0012), in which he further develops his scenario.

(c) How did life come to be left-handed?

Two enantiomers [mirror images] of a generic amino acid which is chiral [left- or right-handed]. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

The left-handedness of amino acids in living things, coupled with the fact that that organisms contain only right-handed nucleotides, has puzzled origin-of-life theorists since the time of Pasteur. Does this rule put a natural origin for living things, as Dr. Miller thinks? It is interesting to note that Pasteur himself was wary of drawing this conclusion, according to a biography written by his grandson, and he even wrote: “I do not judge it impossible.” (René Dubos, Louis Pasteur: Free Lance of Science, Da Capo Press, Inc., 1950. p 396.)

Pasteur’s caution turns out to have been justified. According to a 2015 report by Claudia Lutz in Phys.org titled, Straight up, with a twist: New model derives homochirality from basic life requirements, scientists at the University of Illinois have recently come up with a simple model which explains the chirality found in living organisms in terms of just two basic properties: self-replication and disequilibrium.

The Illinois team wanted to develop a … model, … based on only the most basic properties of life: self-replication and disequilibrium. They showed that with only these minimal requirements, homochirality appears when self-replication is efficient enough.

The model … takes into account the chance events involving individual molecules — which chiral self-replicator happens to find its next substrate first. The detailed statistics built into the model reveal that if self-replication is occurring efficiently enough, this incidental advantage can grow into dominance of one chirality over the other.

The work leads to a key conclusion: since homochirality depends only on the basic principles of life, it is expected to appear wherever life emerges, regardless of the surrounding conditions.

More recent work has provided a detailed picture of how life’s amino acids became left-handed. In 2016, Rowena Ball and John Brindley proposed that since hydrogen peroxide is the smallest, simplest molecule to exist as a pair of non-superimposable mirror images, or enantiomers, its interactions with ribonucelic acids may have led to amplification of D-ribonucleic acids and extinction of L-ribonucleic acids. Hydrogen peroxide was produced on the ancient Earth, more than 3.8 billion years ago, around the time that life emerged. Ball explains how this favored the emergence of right-handed nucleotide chains, in a recent article in Phys.org:

It is thought that a small excess of L-amino acids was “rained” onto the ancient Earth by meteorite bombardment, and scientists have found that a small excess of L-amino acids can catalyse formation of small excesses of D-nucleotide precursors. This, we proposed, led to a marginal excess of D-polynucleotides over L-polynucleotides, and a bias to D-chains of longer mean length than L-chains in the RNA world.

In the primordial soup, local excesses of one or other hydrogen peroxide enantiomer would have occurred. Specific interactions with polynucleotides destabilise the shorter L-chains more than the longer, more robust, D-chains. With a greater fraction of L-chains over D-chains destabilised, hydrogen peroxide can then “go in for the kill”, with one enantiomer (let us say M) preferentially oxidising L-chains.

Overall, this process works in favour of increasing the fraction and average length of D-chains at the expense of L-species.

An outdated argument relating to proteins

In his article, Dr. Miller puts forward an argument for proteins having been intelligently designed, which unfortunately rests on faulty premises:

Proteins eventually break down, and they cannot self-replicate. Additional machinery was also needed to constantly produce new protein replacements. Also, the proteins’ sequence information had to have been stored in DNA using some genetic code, where each amino acid was represented by a series of three nucleotides know as a codon in the same way English letters are represented in Morse Code by dots and dashes. However, no identifiable physical connection exists between individual amino acids and their respective codons. In particular, no amino acid (e.g., valine) is much more strongly attracted to any particular codon (e.g., GTT) than to any other. Without such a physical connection, no purely materialistic process could plausibly explain how amino acid sequences were encoded into DNA. Therefore, the same information in proteins and in DNA must have been encoded separately.

The problem with this argument is that scientists have known for decades that its key premise is false. Dennis Venema (Professor of Biology at Trinity Western University in Langley, British Columbia) explains why, in a Biologos article titled, Biological Information and Intelligent Design: Abiogenesis and the origins of the genetic code (August 25, 2016):

Several amino acids do in fact directly bind to their codon (or in some cases, their anticodon), and the evidence for this has been known since the late 1980s in some cases. Our current understanding is that this applies only to a subset of the 20 amino acids found in present-day proteins.

In Venema’s view, this finding lends support to a particular hypothesis about the origin of the genetic code, known as the direct templating hypothesis, which proposes that “the tRNA system is a later addition to a system that originally used direct chemical interactions between amino acids and codons.” Venema continues: “In this model, then, the original code used a subset of amino acids in the current code, and assembled proteins directly on mRNA molecules without tRNAs present. Later, tRNAs would be added to the system, allowing for other amino acids—amino acids that cannot directly bind mRNA — to be added to the code.” The model also makes a specific prediction: if it is correct, then “amino acids would directly bind to their codons on mRNA, and then be joined together by a ribozyme (the ancestor of the present-day ribosome).”

Venema concludes:

The fact that several amino acids do in fact bind their codons or anticodons is strong evidence that at least part of the code was formed through chemical interactions — and, contra [ID advocate Stephen] Meyer, is not an arbitrary code. The code we have — or at least for those amino acids for which direct binding was possible — was indeed a chemically favored code. And if it was chemically favored, then it is quite likely that it had a chemical origin, even if we do not yet understand all the details of how it came to be.

I will let readers draw their own conclusions as to who has the better of the argument here: Venema or Miller.

3. Free Energy and the Origin of Life: Natural Engines to the Rescue

Photograph of American scientist Josiah Willard Gibbs (1839-1903), discoverer of Gibbs free energy, taken about 1895. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In his third article, Free Energy and the Origin of Life: Natural Engines to the Rescue, Dr. Miller argues that the emergence of life would have required chemicals to move from a state of high entropy and low free energy to one of low entropy and high free energy. (Gibbs free energy can be defined as “a thermodynamic potential that can be used to calculate the maximum of reversible work that may be performed by a thermodynamic system at a constant temperature and pressure.”) However, spontaneous natural processes always tend towards lower free energy. An external source of energy doesn’t help matters, either, as it increases entropy. Miller concludes that life’s formation was intelligently directed:

Now, I will address attempts to overcome the free-energy barriers through the use of natural engines. To summarize, a fundamental hurdle facing all origin-of-life theories is the fact that the first cell must have had a free energy far greater than its chemical precursors. And spontaneous processes always move from higher free energy to lower free energy. More specifically, the origin of life required basic chemicals to coalesce into a state of both lower entropy and higher energy, and no such transitions ever occur without outside help in any situation, even at the microscopic level.

Attempted solutions involving external energy sources fail since the input of raw energy actually increases the entropy of the system, moving it in the wrong direction. This challenge also applies to all appeals to self-replicating molecules, auto-catalytic chemical systems, and self-organization. Since all of these processes proceed spontaneously, they all move from higher to lower free energy, much like rocks rolling down a mountain. However, life resides at the top of the mountain. The only possible solutions must assume the existence of machinery that processes energy and directs it toward performing the required work to properly organize and maintain the first cell.

But as we saw above, Dr. Jeremy England maintains that increasing the entropy of a non-equilibrium dissipative system can promote the formation of complex chemical structures required for life to exist. Miller’s claim that external energy sources invariably increase the entropy of the system is correct if we consider the system as a whole, including the bath into which non-equilibrium dissipative systems can dump their heat. Internally, however, self-organization can reduce entropy- a fact which undermines Miller’s attempt to demonstrate the impossibility of abiogenesis.

4. Origin of Life and Information — Some Common Myths

A game of English-language Scrabble in progress. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In his final installment, Origin of Life and Information — Some Common Myths, Dr. Miller takes aim at the view that a reduction in entropy is sufficient to account for the origin of biological information. Miller puts forward three arguments which he believes demonstrate the absurdity of this idea.

(a) Could a reduction in entropy generate functional information?

A bowl of alphabet soup nearly full, and nearly empty, spelling “THE END” in the latter case. Image courtesy of strawberryblues and Wikipedia.

Let’s look at Miller’s first argument, that a reduction in entropy could never account for the highly specific sequencing of amino acids in proteins, or nucleotides in DNA:

A common attempt to overcome the need for information in the first cell is to equate information to a reduction in entropy, often referred to as the production of “negative entropy” or N-entropy. … However, entropy is not equivalent to the information in cells, since the latter represents functional information. To illustrate the difference, imagine entering the kitchen and seeing a bowl of alphabet soup with several letters arranged in the middle as follows:

REST TODAY AND DRINK PLENTY OF FLUIDS

I HOPE YOU FEEL BETTER SOON

You would immediately realize that some intelligence, probably your mother, arranged the letters for a purpose. Their sequence could not possibly be explained by the physics of boiling water or the chemistry of the pasta.

… You would immediately recognize that a reduction in thermal entropy has no physical connection to the specific ordering of letters in a meaningful message. The same principle holds true in relation to the origin of life for the required sequencing of amino acids in proteins or nucleotides in DNA.

This, I have to say, is a fallacious argument, which I refuted in my online review of Dr. Douglas Axe’s recently published book, Undeniable. Dr. Miller, like Dr. Axe, is confusing functional information (which is found in living things) with the semantic information found in a message written with the letters of the alphabet, such as “REST TODAY AND DRINK PLENTY OF FLUIDS.” In fact, functional information is much easier to generate than semantic information, because it doesn’t have to form words, conform to the rules of syntax, or make sense at the semantic level:

The concepts of meaning and function are quite different, for reasons I shall now explain.

In order for an accidentally generated string of letters to convey a meaningful message, it needs to satisfy three very stringent conditions, each more difficult than the last: first, the letters need to be arranged into meaningful words; second, the sequence of words has to conform to the rules of syntax; and finally, the sequence of words has to make sense at the semantic level: in other words, it needs to express a meaningful proposition. For a string of letters generated at random to meet all of these conditions would indeed be fantastically improbable. But here’s the thing: living things don’t need to satisfy any of these conditions... The sequence of amino acids in a protein needs to do just one thing: it needs to fold up into a shape that can perform a biologically useful task. And that’s it. Generating something useful by chance – especially something with enough useful functions to be called alive – is a pretty tall order, but because living things lack the extra dimensions of richness found in messages that carry a semantic meaning, they’re going to be a lot easier to generate by chance than (say) instruction manuals or cook books… In practical terms, that means that given enough time, life just might arise.

Let me be clear: I am not trying to argue that a reduction in entropy is sufficient to account for the origin of biological information. That strikes me as highly unlikely. What I am arguing, however, is that appeals to messages written in text are utterly irrelevant to the question of how biological information arose. I might also add that most origin-of-life theorists don’t believe that the first living things contained highly specific sequences of “amino acids in proteins or nucleotides in DNA,” as Miller apparently thinks, because they probably lacked both proteins and DNA, if the RNA World hypothesis (discussed below) is correct. Miller is attacking a straw man.

(b) Can fixed rules account for the amino acid sequencing in proteins?

Dr. Miller’s second argument is that fixed rules, such as those governing non-linear dynamics processes, would be unable to generate the arbitrary sequences of amino acids found in proteins. These sequences perform useful biological functions, but are statistically random:

A related error is the claim that biological information could have come about by some complex systems or non-linear dynamics processes. The problem is that all such processes are driven by physical laws or fixed rules. And, any medium capable of containing information (e.g., Scrabble tiles lined up on a board) cannot constrain in any way the arrangement of the associated symbols/letters. For instance, to type a message on a computer, one must be free to enter any letters in any order. If every time one typed an “a” the computer automatically generated a “b,” the computer could no longer contain the information required to create meaningful sentences. In the same way, amino acid sequences in the first cell could only form functional proteins if they were free to take on any order…

…To reiterate, no natural process could have directed the amino acid sequencing in the first cell without destroying the chains’ capacity to contain the required information for proper protein folding. Therefore, the sequences could never be explained by any natural process but only by the intended goal of forming the needed proteins for the cell’s operations (i.e., teleologically).

Dr. Miller has a valid point here: it is extremely unlikely that fixed rules, by themselves, can explain the origin of biological information. Unfortunately, he spoils his case by likening the information in a protein to a string of text. As we have seen, the metaphor is a flawed one, on three counts. Proteins contain functional information, not semantic information.

Dr. Miller also makes an illicit inference from the statement that “no natural process could have directed the amino acid sequencing in the first cell” to the conclusion that “the sequences could never be explained by any natural process,” but only by a teleological process of Intelligent Design. This inference is unwarranted on two counts. First, it assumes that the only kind of natural explanation for the amino acid sequences in proteins would have to be some set of fixed rules (or laws) directing their sequence, which overlooks the possibility that functional sequences may have arisen by chance. (At this point, Intelligent Design advocates will be sure to cite Dr. Douglas Axe’s estimate that only 1 in 10^77 sequences of 150 amino acids are capable of folding up and performing some useful biological function, but this figure is a myth.)

Second, teleology may be either intrinsic (e.g. hearts are of benefit to animals, by virtue of the fact that they pump blood around the body) or extrinsic (e.g. a machine which is designed for the benefit of its maker), or both. Even if one could show that a teleological process was required to explain the origin of proteins, it still needs to be shown that this process was designed by an external Intelligence.

(c) Can stereochemical affinity account for the origin of the genetic code?

Origin-of-life researcher Eugene Koonin in May 2013. Koonin is a Russian-American biologist and Senior Investigator at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Image courtesy of Konrad Foerstner and Wikipedia.

Dr. Miller then goes on to criticize the stereochemical affinity hypothesis for the origin of the genetic code, citing the work of Dr. Eugene Koonin:

A third error relates to attempts to explain the genetic code in the first cell by a stereochemical affinity between amino acids and their corresponding codons. According to this model, naturally occurring chemical processes formed the basis for the connection between amino acids and their related codons (nucleotide triplets). Much of the key research promoting this theory was conducted by biochemist Michael Yarus. He also devised theories on how this early stereochemical era could have evolved into the modern translation system using ribosomes, tRNAs, and supporting enzymes. His research and theories are clever, but his conclusions face numerous challenges.

…For instance, Andrew Ellington’s team questioned whether the correlations in these studies were statistically significant, and they argued that his theories for the development of the modern translation system were untenable. Similarly, Eugene Koonin found that the claimed affinities were weak at best and generally unconvincing. He argued instead that the code started as a “frozen accident” undirected by any chemical properties of its physical components.

I should point out here that some of the articles which Miller links to here are rather old. For example, the article by Andrew Ellington’s team questioning the statistical significance of the correlations identified by Yarus dates back to 2000, while Koonin’s critique dates back to 2008. This is significant, as Yarus et al. published an article in 2009 presenting some of their strongest statistical evidence for the stereochemical model they were proposing:

Using recent sequences for 337 independent binding sites directed to 8 amino acids and containing 18,551 nucleotides in all, we show a highly robust connection between amino acids and cognate coding triplets within their RNA binding sites. The apparent probability (P) that cognate triplets around these sites are unrelated to binding sites is [about] 5.3 x 10-45 for codons overall, and P [is about] 2.1 x 10-46 for cognate anticodons. Therefore, some triplets are unequivocally localized near their present amino acids. Accordingly, there was likely a stereochemical era during evolution of the genetic code, relying on chemical interactions between amino acids and the tertiary structures of RNA binding sites. (Michael Yarus, Jeremy Joseph Widmann and Rob Knight, “RNA–Amino Acid Binding: A Stereochemical Era for the Genetic Code,” in Journal of Molecular Evolution, November 2009; 69(5):406-29, DOI 10.1007/s00239-009-9270-1.)

Dr. Miller also neglects to mention that while Dr. Eugene Koonin did indeed critique Yarus’ claims in the more recent 2017 article he linked to, Koonin actually proposed his own variant of the stereochemical model for the origin of the genetic code:

The conclusion that the mRNA decoding in the early translation system was performed by RNA molecules, conceivably, evolutionary precursors of modern tRNAs (proto-tRNAs) [89], implies a stereochemical model of code origin and evolution, but one that differs from the traditional models of this type in an important way (Figure 2). Under this model, the proto-RNA-amino acid interactions that defined the specificity of translation would not involve the anticodon (let alone codon) that therefore could be chosen arbitrarily and fixed through frozen accident. Instead, following the reasoning outlined previously [90], the amino acids would be recognized by unique pockets in the tertiary structure of the proto-tRNAs. The clustering of codons for related amino acids naturally follows from code expansion by duplication of the proto-tRNAs; the molecules resulting from such duplications obviously would be structurally similar and accordingly would bind similar amino acids, resulting in error minimization, in accord with Crick’s proposal (Figure 2).

Apparently, the reason why Koonin considers that “attempts to decipher the primordial stereochemical code by comparative analysis of modern translation system components are largely futile” is that “[o]nce the amino acid specificity determinants shifted from the proto-tRNAs to the aaRS, the amino acid-binding pockets in the (proto) tRNAs deteriorated such that modern tRNAs showed no consistent affinity to the cognate amino acids.” Koonin proposes that “experiments on in vitro evolution of specific aminoacylating ribozymes that can be evolved quite easily and themselves seem to recapitulate a key aspect of the primordial translation system” might help scientists to reconstruct the original code, at some future date.

Although (as Dr. Miller correctly notes) Koonin personally favors the frozen accident theory for the origin of the genetic code, he irenically proposes that “stereochemistry, biochemical coevolution, and selection for error minimization could have contributed synergistically at different stages of the evolution of the code [43] — along with frozen accident.”

Positive evidence against the design of the genetic code

But there is much more to Koonin’s article. Koonin presents damning evidence against the hypothesis that the standard genetic code (or SGC) was designed, in his article. The problem is that despite the SGC’s impressive ability to keep the number of mutational and translational errors very low, there are lots of other genetic codes which are even better:

Extensive quantitative analyses that employed cost functions differently derived from physico-chemical properties of amino acids have shown that the code is indeed highly resilient, with the probability to pick an equally robust random code being on the order of 10−7–10−8 [14,15,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. Obviously, however, among the ~1084 possible random codes, there is a huge number with a higher degree of error minimization than the SGC [standard genetic code – VJT]. Furthermore, the SGC is not a local peak on the code fitness landscape because certain local rearrangements can increase the level of error minimization; quantitatively, the SGC is positioned roughly halfway from an average random code to the summit of the corresponding local peak [15] (Figure 1).

Let’s do the math. There are about 1084 possible genetic codes. The one used by living things is in the top 1 in 100 million (or 1 in 108). That means that there are 1076 possible genetic codes that are better than it. To make matters worse, it’s not even the best code in its local neighborhood. It’s not “on top of a hill,” as it were. It’s about half-way up the hill. Now ask yourself: if the genetic code were intelligently designed, is this a result that one would expect?

It is disappointing that Dr. Miller fails to appreciate the significance of this evidence against design, presented by Koonin. Sadly, he never even mentions it in his article.

The RNA World – fatally flawed?

A comparison of RNA (left) with DNA (right), showing the helices and nucleobases each employs. Image courtesy of Access Excellence and Wikipedia.

Finally, Dr. Miller concludes with a number of critical remarks about the RNA world hypothesis. Before we proceed further, a definition of the hypothesis might be in order:

All RNA World hypotheses include three basic assumptions: (1) At some time in the evolution of life, genetic continuity was assured by the replication of RNA; (2) Watson-Crick base-pairing was the key to replication; (3) genetically encoded proteins were not involved as catalysts. RNA World hypotheses differ in what they assume about life that may have preceded the RNA World, about the metabolic complexity of the RNA World, and about the role of small-molecule cofactors, possibly including peptides, in the chemistry of the RNA World.

(Michael P. Robertson and Gerald F. Joyce, The Origins of the RNA World, Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, May 2012; 4(5): a003608.)

In the article cited above, Robertson and Joyce summarize the evidence for the RNA World:

There is now strong evidence indicating that an RNA World did indeed exist on the early Earth. The smoking gun is seen in the structure of the contemporary ribosome (Ban et al. 2000; Wimberly et al. 2000; Yusupov et al. 2001). The active site for peptide-bond formation lies deep within a central core of RNA, whereas proteins decorate the outside of this RNA core and insert narrow fingers into it. No amino acid side chain comes within 18 Å of the active site (Nissen et al. 2000). Clearly, the ribosome is a ribozyme (Steitz and Moore 2003), and it is hard to avoid the conclusion that, as suggested by Crick, “the primitive ribosome could have been made entirely of RNA” (1968).

A stronger version of the RNA World hypothesis is that life on Earth began with RNA. In the article cited above, Robertson and Joyce are very frank about the difficulties attending this hypothesis, even referring to it as “The Prebiotic Chemist’s Nightmare.” Despite their sympathies for this hypothesis, the authors suggest that it may be fruitful to consider “the alternative possibility that RNA was preceded by some other replicating, evolving molecule, just as DNA and proteins were preceded by RNA.”

The RNA World hypothesis has its scientific advocates and critics. In a recent article in Biology Direct, Harold S. Bernhardt describes it as “the worst theory of the early evolution of life (except for all the others),” in a humorous adaptation of Sir Winston Churchill’s famous comment on democracy. Referee Eugene Koonin agrees, noting that “no one has achieved bona fide self-replication of RNA which is the cornerstone of the RNA World,” but adding that “there is a lot going for the RNA World … whereas the other hypotheses on the origin of life are outright helpless.” Koonin continues: “As Bernhardt rightly points out, it is not certain that RNA was the first replicator but it does seem certain that it was the first ‘good’ replicator.”

In 2009, Gerald Joyce and Tracey Lincoln of the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, managed to create an RNA enzyme that replicates itself indirectly, by joining together two short pieces of RNA to create a second enzyme, which then joins together another two RNA pieces to recreate the original enzyme. Although the cycle was capable of being continued indefinitely, given an input of suitable raw materials, the enzymes were only able to do their job if they were given the correct RNA strands, which Joyce and Lincoln had to synthesize.

The RNA world hypothesis received a further boost in March 2015, when NASA scientists announced for the first time that, using the starting chemical pyrimidine, which is found in meteorites, they had managed to recreate three key components of DNA and RNA: uracil, cytosine and thymine. The scientists used an ice sample containing pyrimidine exposed to ultraviolet radiation under space-like conditions, in order to produce these essential ingredients of life. “We have demonstrated for the first time that we can make uracil, cytosine, and thymine, all three components of RNA and DNA, non-biologically in a laboratory under conditions found in space,” said Michel Nuevo, research scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California. “We are showing that these laboratory processes, which simulate conditions in outer space, can make several fundamental building blocks used by living organisms on Earth.”

As if that were not enough, more good news for the hypothesis emerged in 2016. RNA is composed of four different chemical building blocks: adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and uracil (U). Back in 2009, a team of researchers led by John Sutherland showed a plausible series of chemical steps which might have given rise to cytosine and uracil, which are also known as pyrimidines, on the primordial Earth.However, Sutherland’s team wasn’t able to explain the origin of RNA’s purine building blocks, adenine and guanine. At last, a team of chemists led by Thomas Carell, at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in Germany, has filled in this gap in scientists’ knowledge. They’ve found a synthetic route for making purines. To be sure, problems remain, as reporter Robert Service notes in a recent article in Science magazine (‘RNA world’ inches closer to explaining origins of life, May 12, 2016):

…Steven Benner, a chemist and origin of life expert at the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in Alachua, Florida… agrees that the newly suggested purine synthesis is a “major step forward” for the field. But even if it’s correct, he says, the chemical conditions that gave rise to the purines still don’t match those that Sutherland’s group suggests may have led to the pyrimidines. So just how As, Gs, Cs, and Us would have ended up together isn’t yet clear. And even if all the RNA bases were in the same place at the same time, it’s still not obvious what drove the bases to link up to form full-fledged RNAs, Benner says.

I conclude that whatever difficulties attend the RNA World hypothesis, they are not fatal ones. Miller’s case for the intelligent design of life is far from closed.

Conclusion

James M. Tour is a synthetic organic chemist, specializing in nanotechnology. Dr. Tour is the T. T. and W. F. Chao Professor of Chemistry, Professor of Materials Science and NanoEngineering, and Professor of Computer Science at Rice University in Houston, Texas. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

At the beginning of this post, I invited my readers to consider the question of whether Dr. Miller has made a strong scientific case for Intelligent Design. Now, I would happily grant that he has highlighted a number of difficulties for any naturalistic theory of the origin of life. But I believe I have shown that Dr. Miller’s positive case for Intelligent Design consists largely of trying to put a full stop where science leaves a comma. Dr. Miller seems to have ignored recent developments in the field of origin-of-life research, which remove at least some of the difficulties he alludes to in his articles. I think an unbiased reader would have to conclude that Miller has failed to demonstrate, to even a high degree of probability, the need for a Designer of life.

I’d like to finish with two quotes from an online essay (Origin of Life, Intelligent Design, Evolution, Creation and Faith) by Dr. James Tour, a very fair-minded chemist who has written a lot about the origin of life:

I have been labeled as an Intelligent Design (sometimes called “ID”) proponent. I am not. I do not know how to use science to prove intelligent design although some others might. I am sympathetic to the arguments and I find some of them intriguing, but I prefer to be free of that intelligent design label. As a modern-day scientist, I do not know how to prove intelligent design using my most sophisticated analytical tools— the canonical tools are, by their own admission, inadequate to answer the intelligent design question. I cannot lay the issue at the doorstep of a benevolent creator or even an impersonal intelligent designer. All I can presently say is that my chemical tools do not permit my assessment of intelligent design.

and

Those who think scientists understand the issues of prebiotic chemistry are wholly misinformed. Nobody understands them. Maybe one day we will. But that day is far from today.

Amen to both.

Sure but then ID is theology not science

Interesting! While I agree that no explanation is better than Making Shit Up, the very existence of belief in gods demonstrates that people simply do not think that way. Instead of admitting ignorance, they dream up wildly irrational “explanations” (gods) utterly without supporting evidence.

So I take it your formal position is that we are totally ignorant, and that NOBODY has the slightest clue about the diversity of life? Or are you taking the position that YOU have no clue, and that those who claim it’s evolution (or gods) are just concocting nonsense rather than admitting ignorance?

These examples, while appropriate, are missing most of the forest – parasites. Parasites have generally simplified their body plans because their hosts provide life support. And there are far more species of parasites than there are species of hosts. And that’s not even counting viruses as parasites.

Well, unless you choose to regard reality as a testing mechanism, which has been working successfully for a few billion years now. And, of course, unless you regard the selection feedback process as serendipity. I think most people would see things that way. We wouldn’t be here if reality didn’t test, and lacked the serendipity of selection feedback.

Yes, excellent point.

Now now, Alan might come along and remind you to stay within the rules. he won’t actually do anything about it mind you, but he might just give a friendly reminder, because hey, you generally follow the rules so well.

Now, if it was me who wrote that, of course Alan would have to say I am a rules breaker and need to be punished, but now now Adapa, we are friends, so let’s just give a gentle reminder to everyone, not pointing any fingers now, just keep in line. We won’t block your posting privileges like we might do to some theist who went around calling people fucking idiots and fucking retards.

Though, I have to be careful, I might just get reprimanded for pointing this hypocrisy out.

Adapa,

What a fucking retard you are. If you even had half a brain cell, maybe it could talk to the quarter brain cell you have now, and say, you are the fucking dumbest waste of carbon that has every existed in the entire universe. There is not even a word to describe how dam stupid your minuscule little neo-reflexive, fully retarded nerve spasm you call a brain is.

The first thing that would happen if you ever did get a brain, is it would tell you to give itself up to science so they could study how any electrical current could be so pathetically worthless. Moron.

So phoodoo, are you going to get to some sort of point with those examples I gave of changes to the genetic code which you asked about?

All this talk of brains as opposed to an immaterial soul-mind-thing, you’d think you’ve become one of those terrible materialists I hear so much about.

I asked you to confirm, those are example of changes to the genetic code itself, and not changes to the transcribing of the code, and those are the two examples you gave right?

What do you mean “transcribing”? The code is translated, from RNA nucleotide sequence, into amino acid sequence.

They would constitue examples of both a change to the code and therefore the translation of the code.

Rumraket,

Great! Now let’s return to my original question, shall we?

I said,

And your reply to this was , Well of course we do! I know exactly what kind of mutations do that. And these are the two examples you gave! Now how the hell are these two examples examples of random mutations that effect the genetic code, and make the genetic code less likely to get genetic mutations?? How did anything you added after that pertain to this question.

The answer is precisely NONE.

Furthermore, when you said:

What did you mean by “The” genetic code? Which genetic code, the genetic code of mycoplasm. The genetic code of ancestral mycoplasm? The genetic code of humans? Which genetic code did you mean by THE? All of them?

Don’t give him ideas, OMagain.

I actually explained that. The particular example I gave with the valine residue at position 227 in E coli Valyl-tRNA-synthetse, is one such example.

I see that I need to elaborate. If the valine amino acid is substituted with alanine, the enzyme loses some of it’s specificity and will start to misincorporate threonine in place of valine. Conversely, if this alanine amino acid is substituted with valine, the accuracy is restored and it will no longer misincorporate threonine in place of valine.

Recall that valine is the amino acid at position 227 in this enzyme, which if substituted with alanine, makes it promiscous and start putting threonines in it’s place.

So, the mutation in the coding region of Valyl-tRNA-synthetase that would cause the substitution of alanine for valine in position 227, in a Valyl-tRNA-synthetase, in E coli, will be a mutation that makes it less likely for the translation system in E coli to misincorporate threonines in place of valines. As such, less likely to misincoporate threonines at position 227 in Valyl-tRNA-synthetase in place of the valine that is required for normal accuracy.

So that mutation (that would cause the substitution of alanine for valine) is therefore the perfect example of a mutation to the genetic code that would make it less likely for the genetic code to get mutations.

Okay, I see why it would appear there is a conflict between my two statements there. But I elaborated right after the thing you quoted and that elaboration would have clarified your confusions. In fact the post you quote there is chronologically prior to the one about the Valyl-tRNA-synthetase, so if you had understood this first one, you would have understood that there was no actual conflict.

Here is what follows:

Again I will elaborate and answer your question. You ask:

First of all I meant all of them. Whichever genetic code an organism has will not be the determinant of the mutation rate at replication.

Second, the genetic code does not affect the chance that nucleotide mutations happen when cells divide and the genome is replicated. Put another way, the genetic code does not affect the fidelity of DNA polymerization by DNA polymerases.

The genetic code does affect the chance that those nucleotide mutations (which happen during replication) will in turn cause amino acid mutations in protein coding genes.

So if an organism divides and gets on average 30 nucleotide mutations during replication, and on average only 3 of these nucleotide mutations cause changes in coding regions so amino acids are substituted, then changing this organisms’s genetic code to another will not change the fact that it gets on average 30 nucleotide mutations during replication, but it very well might affect the rate at which those nucleotide mutations result in amino acid mutations in protein coding genes. So when I said the genetic code does not affect the chance of mutation, I implicitly meant the chance of mutations in genomic sequence at replication. I even said this.

Has this cleared up the apparent contradiction for you? If not, feel tree to ask more.

Rumraket,

Why didn’t you quote the beginning of the statement?

Which genetic code doesn’t reduce the chance of mutations? All of them?

Yes, all of them. And I did clarity that I was talking about the chance of mutations at replication. Whichever genetic code an organism has will not be the determinant of the mutation rate at replication.

Again, let me repeat the original question which started this.

Rumraket,

How many genetic codes exist?

We don’t know how many actually exist, but all the ones we have found so far are minor variations of the same basic thing called the Standard Genetic Code (SGC).

Here’s a list of known variants: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Utils/wprintgc.cgi.

I don’t know if that list is exhaustive of all the variants we know of from life we have so far discovered.

Rumraket,

Whoa, whoa, when you talk about the different genetic codes then, they are still the Standard Genetic Code then?

When the mycoplasma changes the genetic code, as you said, is it still the Standard Genetic Code? If the code is changed, are you still calling it the Standard Genetic Code? Change means its a different code, right? The mycoplasm are using a different code than the Standard Genetic Code right?

Of course not, they are minor variations of it. Look at the different code tables on the list and you will see some small differences between them.

No, then it is the mycoplasma version of it. It seems to be listed as numbe 4 on the list.

No. The standard code is at the top, called the Standard Genetic Code or just Standard Code, and on the list it has number 1.

All the different variations from it have their own name and number.

Correct.

Correct.

I know you are very precise with words, so what do you mean by “variations”? When is it a variation, and when is it a different code?

Furthermore you said the mycoplasma in the study you cited, changed their code. They changed it from what? From the variation that was already the variation of the Standard Code?

And what about the e. coli? Is the ancestral e coli, and the e coli in the lab that you said was a change of the genetic code, still part of the same code?

Rumraket,

If there are so many different codes, how do you know which code VJ was talking about in his opening post?

In fact, don’t you find it curious that VJ keeps referencing THE code as if there is only one? And even you, who we know is very precise with words, you keep using the word THE when referring to a genetic code. And oddly enough, YOU keep repeating the phrase “the genetic code”, but there are many genetic codes right, so was it a typing error?

A variation would be a different code, those two terms are not mutually exclusive. When the term variant is used it is only to emphasise that it is still much more similar to the standard genetic code, than it is different from it. Meaning that out of the 64 codons, usually between one and four are different.

To be clear, I take you to be asking if the variant from mycoplasma with a “statistical proteome” I cited earlier, constitutes a further variation from the “normal” mycoplasma variant of the Standard Genetic Code, reported on the NCBI list of codes.

Good question, haven’t actually looked into that. As far as I can gather now, yes it is a further variation from the mycoplasma code listed under number 4 on the NCBI list.

The position 227 substitution that renders the Valyl-tRNA-synthase more promiscous would constitute a further deviation from the E coli variant of the Standard Genetic Code.

The particular argument we spoke about there, the one about the non-optimal level of error minimization of the Standard Genetic Code, applies to all known variants of the Standard Genetic Code.

I don’t find that curious at all, because I know that it is called the Standard Genetic Code exactly because even though variations of it exist, they are so minor that the arguments pertaining to it’s level of error minimization do not substantially differ were we to posit any of the variants in it’s place.

No, it was not a typing error. It was not any form of error at all. I deliberately used the word genetic code because the minor variations of it that do exist do not substantially alter it’s properties such that it undermines any argument relating to the non-optimal level of error-minimization of any of them. None of the variants discovered are the best possible code wrt error minimization out of the 10^84 possible codes with a similar block structure. And several of them are worse.

Hey phoodoo, if the Standard Genetic Code, or any of it’s known close variations, was found to be the best possible code with respect to the level of error minimization it provides, would you consider that to be a piece of evidence that is more plausible (as in more likely) on intelligent design, than on evolution, and as such to be evidence for intelligent design?

Wow, word usage is really getting interesting now! Whats the name of the variation of the variation of the e coli?

Is there a name for the variation of the variation of The Mold, Protozoan, and Coelenterate Mitochondrial Code and the Mycoplasma/Spiroplasma Code?

So a variation, and a different code, those two uses mean the same thing huh?

So really, there is only ONE living thing on Earth. Sure there are variations, but its still the Standard Living Thing. This is very informative. I think we might have invented a whole new language. Its the same language of course, just like Chinese and Japanese are the same, just variations.

So then when I asked you, if the mycoplasm study which you referenced, was an example of a new genetic code, and you answered yes, ACTUALLY what you meant was mycoplasm use a different code than THE STANDARD CODE, and you didn’t have any idea if that was a new code once again. So THAT study, that you gave as an example of how we can get a mutation to the CODE, (which we can’t really be sure if you mean The Code or A Code any more, because we are using a new dialect now, which I guess means every code is both new and also the same, but with variation that is not meaningful, because it basically the same thing), what it now seems you were trying to say was that all mycoplasma use a slightly different version of the standard code, and the paper you referenced you don’t even know if that was an example of a new code forming. Mycoplasma ALWAYS use a slightly different code. So your reasons for referencing it are now even more murky.

I think you might have been boasting a bit early.

No not really, because when you say the ‘best” I have no idea if being the best at some target you are choosing has any meaning at all. Maybe its the best at making green, I don’t know.

I am not sure that making green is any objective.

On the list from NCBI, it’s called “11. The Bacterial, Archaeal and Plant Plastid Code”.

That is the name.

Those two can mean the same thing or they can not, the contexts determine which sense to use.

As above, there are several different ways to understand the term. There actually is a sense in which what you say is correct, in that all life on Earth is cellular life. And there are many variations of cellular life, but they’re all cells.

I don’t think so, I think we’re still just speaking english.

It is apparent to me that there are senses in which Chinese and Japanese can be understood to be variations of the same thing. They’re variations of languages and they probably do share some similarities yes.

I did not know whether the particular reference I gave to a mycoplasma with a statistical proteome constituted a further variation of the mycoplasma code, which was already a variant of the Standard Genetic Code. Correct.

We aren’t. Still just english.

It has differences from the SGC, so it is different from the SGC, but those differences are so minor that the argument relating to the level of error minimization of the SGC is not substantially altered.

You’ve forgotten why I referenced that mycoplasma paper now it seems. That was to substantiate that there are organisms in existence right now with elements of a statistical proteome. Whether that also constitutes a further deviation from the “normal” mycoplasma code was entirely irrelevant to the point I was making.

Recall that up here above you asked “I asked you to confirm, those are example of changes to the genetic code itself, and not changes to the transcribing of the code, and those are the two examples you gave right?”

I confirmed that those were indeed examples of changes to the genetic code itself. And they are. Whether we understand the term “the genetic code itself” to refer to the SGC, or the mycoplasma code, it would STILL constitute an example of a change to it whichever sense we use. So I was right.

It is not in the least murky, it didn’t start out murky and it has only gotten even clearer since we began, as I have elaborated extensively every time you got more desperate to try to goad me into making some sort of error you could gloat about.

I think, in conclusion, you’ve really just made a fool of yourself once again.

I have been boasting at the exactly appropriate times. I feel pretty good about myself at this very moment. And I thank you for taking up once again the subject about how I personally might feel and act in this discussion, proving once again that you’re ruled almost entirely by emotion (to you, this is about who gets to win, and “boast”), rather than reason and evidence.

You have too much invested here. Too much pride. It is no longer worth my time. Thank you for playing, welcome back to ignore.

You’ve been told a dozen times what the criteria is (minimizing the deleterious effects of random mutations) and why it’s important. The fact that you still don’t get it is nobody’s fault but your own.

Your retarded caricatures only make you look even dumber.

Throw another tantrum now

No, no it isn’t Rumraket. That apparently is the name of the e.coli variant of the Standard Code (which you are calling both the same code and a different code). But I asked you what is the name of the variation of the variation- I think that should have been clear enough.

I haven’t forgotten why you say you referenced that paper, I am simply still perplexed about why you referenced that paper. Who was asking you to show if there existed elements of a statistical proteome? I am pretty sure I would would remember if I ever asked you that. I am also perplexed that when I asked you if that constituted a new genetic code, you said yes, and today you are saying, well, I don’t really know. Could be. You still seem to have entirely missed the whole point of what got you started in your rant to begin with, which we can now see was way off the mark.

What I asked was, what would a mutation to the Standard Genetic Code, which made the Standard Genetic Code no longer susceptible to getting mutations to the Standard Genetic Code look like. You tried to literature bluff your way around it, and you thought I would not notice.

Sorry if your feelings are hurt. I guess you just have too much invested.

Rumraket thanks and a tip of the cap to you for the excellent tutorial you’ve been providing. I especially applaud your patience in trying to educate a recalcitrant shit-for-brains Creationist who desperately doesn’t want to learn or understand. The phrase “casting pearls before swine” comes to mind.

Adapa,

Keep your gay fantasies to yourself will ya?

phoodoo,

Please watch those insults.

Yes, I know you didn’t start this round. But please try to stop. Otherwise, I will have to get heavy handed with guanoing.

Adapa,

My comment about cutting out the insults applies to you, too — and, actually, all should take notice.

Moved a comment to guano. Comments about moderating belong in the Moderation Issues thread. We don’t operate a 24 hour service and regret that some guano-worthy comments get missed.

And another. Complain in the appropriate thread, please.

And another.

Alan Fox,

LOL! You’re probably the only guy here who can out-asshole Mung. Well done!

Why should all take notice Neil?

Its not like you can be expected to see EVERY post. So its not like your partisan hack bullshit is REALLY partisan hack bullshit-its just that you can’t see very well. And coincidentally Alan has the same astigmatism. Talk about weird serendipity. So I don’t think anyone should really pay attention. I mean the odds of you actually reading and comprehending an offending post-astronomical. 10 to the 84th at the very most. No chance at all. How could you? What are you, soothsayers? Sometimes they are two posts removed-who can see that!!

So while some good advice can often be appreciated, this is just being too superfluous Neil. Its like saying, hey watch out, there could be a frozen cow thrown from a tornado landing on your head. Be careful!

But Keep up the good work Neil and Alan. Proud of you!

I have move a couple of additional posts to guano.

phoodoo,

I’ll take that as the compliment it surely is! Thank-you! 🙂

Flint,

Can you support the claim that supporting God or a Creator is without evidence or is made up solely in humans imagination?

Yes, we don’t know the detail of how the diversity of life emerged. There is the materialist version which says we don’t yet have the details but science will eventually close the gap.

There is supporting evidence but closing the gap is a statement of faith.

There is the creationist version that says that what we see is from the creation of God. There is supporting evidence but ultimately the existence of God is a statement of faith.

The fun we are having is trying to decide which side has the strongest case.

Neil Rickert,

Hey Neil, if you are going to move posts for quoting people, you might as well just band me now.

How are we supposed to be able to have a discussions if quoting them is off limits.

You

know what I mean.

The fun we’re having is you pretending to have a case.

Glen Davidson

Posting insults in regular threads is against the rules – and so is posting quotations of those comments. You can be as insulting as you wish in Noyau. Now please stop posting comments complaining about moderation issues in the wrong thread. They will continue to move to guano if I see them.

GlenDavidson,

So if you think this is a closed case why are you wasting your time?

There is hazy, inexact analogy, and not the slightest bit of real match-up of cause and effect. None of your ambiguous “evidence” would hold up in court or in science, because you can’t say via evidence that the Designer would make the biologic patterns that we see, encounter the limits that we see in life, make organisms “for a purpose” only to also make other organisms to destroy them, or to have any reason to make organisms slavishly derivative.

I don’t tend to say that there’s “no evidence” for design, not because that isn’t accurate enough for how people often talk of “no evidence” when the only evidence is weak and inadequate for making the case. But one still might say that there is weak and inadequate evidence for design, rather than that there is none at all in another sense, so I like to include modifiers, like there’s no meaningful evidence for design. You simply don’t have any sort of identifiable cause that would produce what we see in life, all you have is your belief that somehow it must be designed because it’s so complex and because we can’t completely state what happened over four billion years of the past. It’s really poor “evidence,” and arguably (and on some meanings of the word “evidence”) it is none at all.

Glen Davidson

First, it’s not a closed case, because science cares about what did happen that still isn’t known. The ability of people to adequately address the issues is the point, rather than people like you closing off the investigation into what exactly did happen.

Second, there are people genuinely confused by pseudoscience who should be given the knowledge of science that they certainly wouldn’t get from your side.

And why do you ask the same lame questions that have been answered dozens of times, at least?

Glen Davidson