It is not often that I encounter a book which forces me to undergo a fundamental rethink on a vital issue. Michael Alter’s The Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry is one such book. The issue it addresses is whether the New Testament provides good evidence for Jesus’ Resurrection from the dead. Prior to reading Michael Alter’s book, I believed that a Christian could make a strong case for Jesus’ having been raised from the dead, on purely historical grounds. After reading the book, I would no longer espouse this view. Alter has convincingly demolished Christian apologists’ case for the Resurrection – and he’s got another book coming out soon, which is even more hard-hitting than his first one, judging from the excerpts which I’ve read.

Diehard skeptics will of course dismiss the Resurrection as fiction because they reject the very idea of the supernatural, but Michael Alter, a Jewish author who has spent more than a decade researching the Resurrection, isn’t one of these skeptics. Alter willingly grants for the sake of argument the existence of a personal God Who works miracles and Who has revealed Himself in the Hebrew Bible. Despite these generous concessions to his Christian opponents, I have to say that Alter’s book is the most devastating critique of the case for the Resurrection that I have ever read. Rabbi Moshe Shulman, who wrote the Foreword to Alter’s book, explains that what sets it apart from other critiques is an avalanche of evidence, much of it new, which undercuts the very foundations of the historical case for the Resurrection:

…[I]t cannot be denied that this work does present serious reasons to doubt the historicity of the Resurrection. The result is unquestionable. Much of what is here demonstrated is not found in any other work, and even when it does occur in other works, it is not in such an easily understood manner. There may be a point or two in favor of those who believe in the Resurrection that may have been overlooked by accident. But even if this is a given, the preponderance of evidence shows that the Resurrection is myth and not history. It is certainly not something one should base a life’s decision on.

Whether you share the Rabbi’s views on the Resurrection or not (and I don’t), reading Alter’s book will make you realize that what historians know about Jesus’ crucifixion, burial and post-mortem appearances to his disciples is very little: far too little for a Christian to base their belief in the reality of Jesus’ Resurrection on the historical evidence alone. I now believe that only the grace of God could possibly justify making such an intellectual commitment.

WARNING: This will be a very lengthy review, which few people will have time to read in its entirety. For readers whose time is very limited, here’s a brief, 5,000-word executive summary, which will be followed by a main menu that allows readers to navigate their way around the review, as they please, although I would ask serious readers to at least peruse Section A. There is no need to rush: I don’t mind waiting a few days for people’s comments. If the acerbic tone offends some Christian readers, let me remind them that it is not my intent to mock belief in the Resurrection (which I share with them), but to explain why I now regard the enterprise of trying to prove it (or at the very least, demonstrate it to be more probable than not) is a doomed one.

Executive Summary

There are, broadly speaking, two ways of arguing for the Resurrection: first, a “minimal facts” approach (developed by Dr. Gary Habermas and Dr. Mike Licona) which sticks to facts about Jesus and his disciples which are generally accepted by historians, and then proceeds to argue for the Resurrection as the best explanation for those facts; and second, a “maximal data” approach (championed by Drs. Tim and Lydia McGrew) which first seeks to build a cumulative case for the historical reliability of the four Gospel accounts before attempting to argue for the Resurrection. Although Alter does not explicitly deal with either of these approaches in his book – he’ll be critiquing Resurrection apologetics in his second book on the Resurrection, which is forthcoming – the importance of this book which he has written is that it totally discredits both approaches.

The “maximal data” approach stands or falls on the claim that the New Testament is, if not inerrant, at the very least, historically reliable. Alter’s book assembles a mountain of evidence which demonstrates convincingly that it isn’t. In his book, Alter uncovers no less than 120 internal contradictions (relating to 113 different issues) in the New Testament accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion, burial and resurrection, as well as scores of historical inaccuracies.

It turns out that the Gospels are not even historically reliable when narrating Jesus’ Crucifixion, let alone his Resurrection. To illustrate my point, try a little thought experiment: close your eyes and try to picture in your mind Jesus’ Crucifixion. Chances are you imagined a scene like the painting below by Veronese, right?

The Crucifixion by Paolo Veronese (1528-1588). The Louvre Museum, Salle des États. Image courtesy of The Yorck Project (2002) and Wikipedia.

Get ready to revise your picture: Veronese’s painting may be faithful to the Gospels, but for the most part, it’s historically improbable. Nearly everything in the Gospel narratives of the crucifixion turns out to be highly dubious, when judged by the standards which a fair-minded historian would employ. Three of the Gospels tell us that Jesus was crucified on the Passover, and that the Last Supper was a Passover meal (Matthew 26:17-19; Mark 14:12-16; Luke 22:7-15) during which Jesus took some bread and a cup of wine, and then told his disciples to eat his body and to drink blood, which he called “the blood of the new covenant” (Matthew 26:26-29; Mark 14:22-25; Luke 22:17-20; see also 1 Corinthians 11:23-26). Most New Testament historians would consider these claims highly questionable, to say the least. Even former Pope Benedict XVI admits that “the meal that Jesus shared with the Twelve was not a Passover meal according to the ritual prescriptions of Judaism.” To complicate matters, John’s Gospel disagrees with the other three Gospels in placing Jesus’ Last Supper and Crucifixion on the eve of the Passover (John 19:14, 19:31; see here and here below, for more details). Historians generally agree that this is a much more plausible date. So does former Pope Benedict XVI: he acknowledges that “one has to choose between the Synoptic and Johannine chronologies,” and he accepts that “the weight of evidence favours John.”

As for what happened at the Last Supper: Dr. Michael Cahill, Professor of Biblical Studies at Duquesne University, freely acknowledges the unlikelihood of a devout Jew such as Jesus instituting a blood-drinking ceremony, in his article, Drinking Blood at a Kosher Eucharist? The Sound of Scholarly Silence. He concludes: “Those who hold for the literal institution by Jesus have not been able to explain plausibly how the drinking of blood could have arisen in a Jewish setting.” Interestingly, the blood-drinking ceremony at the Last Supper is omitted from John’s Gospel.

All four Gospels agree that Jesus was betrayed by one of his apostles, Judas Iscariot. However, they disagree about practically everything else, when it comes to Judas – in particular, why he betrayed Jesus (was it for money, as Matthew declares, or because Satan entered into his heart, as Luke and John maintain?), when he turned against Jesus (was it two days before the Passover, as in Matthew and Mark, or during the Last Supper, as in John?), and what happened to him after he betrayed Jesus (did he return the money to the chief priests before going out and hanging himself in a fit of remorse, as in Matthew, or did he use the money to buy a field, where he suffered the mishap of his bowels suddenly bursting open, as in Luke’s Acts of the Apostles?) Matthew even manages to bungle the famous prophecy he quotes about the thirty pieces of silver Judas returned to the temple priests: it’s not in Jeremiah, as he claims, but in Zechariah, and it says nothing about Jesus, anyway: the author of the prophecy was writing about the rupture between Israel and Judah.

Again: according to the Evangelists, Jesus was condemned of blasphemy by the Jewish Sanhedrin in a hasty night trial at the residence of the high priest, Caiaphas. But something smells very fishy here: even back in the first century A.D., the trial depicted in the Gospels would have broken just about every rule in the book. It shouldn’t have been at Caiaphas’ residence, it shouldn’t have been held at night, and there should have been a 24-hour delay before a death sentence was pronounced. And nothing that Jesus said during his trial would have constituted blasphemy anyway: he didn’t pronounce the Divine name, and he didn’t claim to be equal to God. There was nothing blasphemous about claiming to be the Son of God. Mark records Jesus referring to himself as the Son of Man, seated on the right hand of God and coming on the clouds of heaven, but similar claims were made by Jews living well before Jesus was born, about the Biblical patriarch Enoch. So why did the Jewish Sanhedrin (Council) decide that Jesus deserved to die? And was their verdict a unanimous one (as in Mark’s Gospel) or were there dissenters (as Luke’s Gospel records)?

Later on, in the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ Roman trial before Pontius Pilate, Pilate is depicted as being very reluctant to condemn Jesus to death, even washing his hands of the case in Matthew’s Gospel – but this contradicts everything we know about the man from contemporaneous Jewish sources (and from Luke himself): in reality, the man was a ruthless, cold-hearted butcher who wouldn’t have had a moment’s hesitation in condemning Jesus to death.

Two of the Gospels (Matthew and Mark) record that Jesus was mocked by the chief priests while hanging on the Cross: “Let the Christ, the King of Israel, come down now from the cross that we may see and believe” (Mark 15:32). But that couldn’t have happened if Jesus was crucified on the eve of the Passover (as in John’s Gospel) rather than on the Passover itself (as in Matthew, Mark and Luke, who, as we’ve seen, got the date wrong): on Passover eve, the chief priests would have been busy slaughtering lambs in the Temple for the thousands of families in Jerusalem wanting to celebrate Passover that evening. It was their busiest day of the year. They wouldn’t have had time to go out to Golgotha and poke fun at Jesus hanging on the Cross.

And that story in Luke’s Gospel about the good thief? Probably didn’t happen either: he’d been languishing in jail for weeks, cut off from all news of the outside world, so how would he have known that Jesus was innocent of any crime and had done nothing wrong? Doesn’t make sense.

And what about those last words Jesus is supposed to have uttered on the Cross? Leaving aside the fact that the Gospels give us three different versions of Jesus’ final words (see Matthew 27:46-50 and Mark 15:34-37; Luke 23:46; John 19:30), all of the words allegedly spoken by Jesus on the Cross are likely to be fictional. The Romans wouldn’t have allowed anyone to stand close enough to the Cross to hear Jesus’ words, in the first place – especially if he was convicted on a political charge, as Jesus was (Matthew 27:37, Mark 15:26, Luke 23:38, John 19:19). And forget about Jesus crying out in a loud voice just before he died: by that time, his voice would have been reduced to a mere whisper by the asphyxiation he suffered while hanging on the Cross. Most ridiculous is the claim, found in Matthew’s and Mark’s Gospels, that after Jesus uttered his final cry on the Cross (“Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?”, or “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?”), some of the bystanders thought he was calling on Elijah. As Alter points out, there’s simply no way any Jew would mistake the word “Eli” for “Elijah.”

John’s Gospel records the presence of Jesus’ mother at the foot of the Cross, along with the beloved disciple (who is generally presumed to have been the apostle John, although about 20 other individuals have been proposed as candidates), but this, too, is probably fictional: Jesus was crucified as an enemy of the State (“King of the Jews”), and as such, the Romans would have shown him no quarter – and they certainly would not have allowed him to enjoy a final conversation with his mother. To quote the words of the late Dr. Maurice Casey (1942-2014), author of Is John’s Gospel True? (1996, London: Routledge, p. 188) and a former Professor of New Testament Languages and Literature at the Department of Theology at the University of Nottingham: “The fourth Gospel’s group of people beside the Cross includes Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple. It is most unlikely that these people would have been allowed this close to a Roman crucifixion.” As Dr. Bart Ehrman, Professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has pointed out in an online essay titled, Why Romans crucified people, the whole aim of crucifixion was to humiliate the victim as much as possible. And when political criminals like Jesus were crucified, the warning to the public was unmistakably clear: this is what happens to you if you mess with Rome. No niceties were observed and no courtesies allowed.

Nor can we trust the beloved disciple’s claim to have witnessed blood and water flowing from Jesus’ side after he was pierced with a soldier’s lance (John 19:31-36): Jesus’ body had already been heavily scourged, so it would have been covered with blood. Consequently, it would have been very difficult to visually distinguish blood and water flowing from Jesus’ side unless the beloved disciple was observing it close-up (which, as we’ve seen, he wasn’t). As Alter points out, the Romans would never have allowed anyone near the Cross while they were breaking the legs of the crucified criminals, in order to make sure they were really dead. Incidentally, the story in John about Jesus managing to avoid having his legs broken by the Roman soldiers is also historically suspect: if Pilate had ordered the soldiers to break the legs of all the criminals, then they would have obeyed his orders to the letter. (John’s story appears to have been written in order to serve a theological agenda, portraying Jesus as the Paschal lamb that was slain without any of its bones being broken – see Exodus 12:46.)

How about the Gospel accounts in Matthew, Mark and Luke (but not John) of the three hours of darkness preceding Jesus’ death? Unfortunately, there’s no documentation of any such event occurring in Palestine at that time. (And no, Thallus and Phlegon don’t help the Christian apologetic case: in fact, they only serve to weaken it, as we’ll see below.) And the earthquake that is said to have taken place at Jesus’ death? Only one Evangelist (Matthew) records it – and he shoots his own credibility in the foot by claiming that the tombs of many Jewish saints were opened, that their bodies were raised to life again, and that they appeared to many people in Jerusalem after Jesus’ Resurrection (Matthew 27:51-54): an astonishing claim which is found in no other Gospel. Even conservative Christian apologists such as Dale Allison, Craig Evans and Mike Licona are highly skeptical of this story.

What about the story of the tearing of the veil of the Temple immediately following Jesus’ death? Doesn’t add up either: as Alter demonstrates in his book, using maps, the veil of the Temple couldn’t even be seen from Golgotha (the place where Jesus was crucified). And while we have accounts in the Jerusalem Talmud and the Babylonian Talmud of strange occurrences connected with the Temple around 30 A.D., neither of them mention the veil of the Temple being torn in two. That sounds very suspicious.

A prudent and impartial historian, weighing up all these difficulties, would surely conclude that the foregoing events described in the Gospels probably never happened. And if the Gospels get so many key facts about Jesus’ crucifixion wrong, then they can no longer be seen as historically reliable; instead, they must be regarded as highly embellished accounts. (I am of course aware that certain advocates of the “maximal data” approach object that an incident-by-incident approach to Gospel reliability is fundamentally wrong; I’ll be responding to their arguments in Section A below. For now, I’ll just say that when the Gospels narrate more than a dozen historically doubtful events during the last 24 hours of Jesus’ life, there’s no way they can be called reliable accounts.) But if the Gospels are not historically reliable, then Christian apologists cannot legitimately appeal to episodes recorded in the Gospels (such as Jesus’ appearance to doubting Thomas) in order to establish Jesus’ Resurrection, without providing independent argumentation that these episodes actually took place.

Wall mosaic of the entombment of Jesus at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Image courtesy of AntanO and Wikipedia.

So much for the “maximal data” approach to Resurrection apologetics, then. The “minimal facts” approach fares no better. Proponents of this approach usually include the discovery of Jesus’ empty tomb on their list of minimal facts, and they proudly cite Professor Gary Habermas’ claim that 75% of New Testament scholars accept the reality of the empty tomb. But Habermas hasn’t released his survey data, and in any case, it’s based on a biased sample: most of the scholars surveyed were committed Christians. What’s more, the survey was completed in 2005, so it’s more than a dozen years out-of-date. For a critique of Habermas’ survey, see here.

In his book, Alter shows that none of the Gospel accounts of Jesus being buried in a new rock tomb owned by Joseph of Arimathea hold water, and in any case they’re mutually contradictory.

Let’s begin with Mark’s Gospel, which depicts Joseph of Arimathea as buying a linen shroud for Jesus on the Passover, a Jewish high holy day (Mark 14:12-16, 15:46). That was forbidden under Jewish law (Leviticus 23:6-7; Nehemiah 10:31). Later, after the Sabbath, the women present at Jesus’ burial buy spices to anoint him (Mark 16:1). But they couldn’t have done it on Saturday night, as the shops would have been closed (remember: there was no electrical lighting in the first century), and there wouldn’t have been time to buy them on Sunday morning either, as the women arrived at Jesus’ tomb just after sunrise (Mark 16:2). Mark’s Gospel also tells us that the tomb was sealed with a large, round stone (Mark 16:3-4), but only fabulously rich people owned tombs like that, back in those days. Luke’s Gospel fares no better than Mark’s, when it comes to historical accuracy: it depicts the women as preparing spices and ointments on a high holy day (Passover), shortly before the beginning of the Jewish Sabbath on Friday evening (Luke 23:56). This, too, would have contravened Jewish law. In any case, Luke’s account of when the spices were purchased contradicts Mark’s: Luke says it was on Friday, while Mark says it was on Sunday morning. Both cannot be right. Luke also tells us that Joseph of Arimathea had not consented to the decision by the council of chief priests and scribes to condemn Jesus to death (Luke 23:51), which contradicts Mark’s and Matthew’s express statements that the entire council voted to condemn Jesus (Mark 14:64, 15:1; Matthew 26:59, 27:1). Incidentally, Luke’s second book, the Acts of the Apostles, contradicts Luke’s Gospel on the question of who buried Jesus: in Acts 13:27-29, it is the rulers of Jerusalem (not Joseph of Arimathea) who take Jesus down from the Cross and lay him in a tomb. Matthew’s account of Jesus’ burial is even more far-fetched than Mark’s and Luke’s: it portrays the chief priests and Pharisees as visiting Pilate on the Jewish Sabbath (Saturday), asking for a guard to be placed over Jesus’ tomb, and personally sealing the stone (Matthew 27:66) – a clear violation of Sabbath law which would have merited the death penalty (Exodus 35:2; Numbers 15:32-36). Additionally, asking Gentile guards to work on the Sabbath (by guarding the tomb) would have violated the commandments of the Torah (Exodus 20:8-10): Jews were forbidden to ask even strangers to work for them on the Sabbath. It’s also preposterous to imagine that Pilate would have agreed to their request on a purely religious matter, which did not concern him – particularly after they had annoyed him the previous day by putting him on the spot and publicly pressuring him to have Jesus put to death (Matthew 27:15-26). The account of Jesus’ burial in John’s Gospel is also full of difficulties. To begin with, there is a puzzling inconsistency: first, the chief priests of “the Jews” ask for the legs of the crucified criminals (including Jesus) to be broken so as to hasten death, so that they might be taken away before the Sabbath (John19:31; cf. John 19:21), which seems to imply that they were being granted custody of the body of Jesus, but then Joseph of Arimathea secretly (“for fear of the Jews”) asks Pilate if he can take away the body of Jesus, and Pilate allows him to do so (John 19:38). This is bizarre: why would Pilate have handed over the body of an enemy of the State to a private individual, anyway? Another man named Nicodemus also comes along to Jesus’ burial, bringing 100 Roman pounds of myrrh and aloes (or 75 of our pounds) – an amount literally fit for a king! In any case, Jesus’ body being packed in spices is historically incongruous, reflecting Egyptian rather than Jewish burial customs. Joseph of Arimathea’s tomb is also said to be situated near the place where Jesus was crucified, but as Alter points out, it is very unlikely that a wealthy man like Joseph would have a tomb in such an undesirable location. Finally, Joseph’s tomb is described in three Gospels (Matthew, Luke and John) as a new tomb, in which no-one had been laid. Once again, this is highly improbable: most likely, it would have been a family tomb, in which several generations of Joseph’s family would have been buried. In short: the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ burial are at odds with Jewish customs – and with each other – on several key points.

As if that were not bad enough, since the publication of Alter’s book, Professor Bart Ehrman has put forward some very powerful arguments (see here and here) explaining why Jesus would probably not have been given a proper burial anyway: as an enemy of the State, the Romans would have wanted to humiliate him completely, so his body would have been left on the Cross for days and been gnawed at by carrion birds and animals, in full view of the public, before being tossed into a common burial pit for criminals. To be sure, leaving a dead body hanging on a cross after sundown would have upset the Jews, but there’s no record of the Romans ever showing any clemency with the body of a political criminal, and allowing it to be given a proper burial.

But even if Jesus had managed to escaped this grisly fate, and the Jewish Sanhedrin had obtained permission to bury Jesus’ body (as suggested by Acts 13:27-29 and John 19:31), it would have been a dishonorable burial, with no family members present, no funeral procession and no rituals of mourning, where the body was most likely buried in a trench grave in a field where the bodies of criminals condemned by Jewish courts were buried, or in a burial cave owned by the Jewish authorities (less likely, as we have no record of any cave being used to bury executed criminals). (The two thieves crucified with Jesus weren’t condemned by a Jewish court but a Roman one, so their bodies wouldn’t have been buried with that of Jesus, if the Jewish chief priests managed to get hold of Jesus’ body.) However, Professor Jodi Magness, an archaeologist who works at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has suggested that there might not have been enough time to dig a trench grave on Friday afternoon, so the chief priests may have asked Joseph (a wealthy member of the council) to temporarily store Jesus’ body in his grave over the weekend. If Dr. Magness’ proposal is correct, it would certainly account for the mention of Joseph of Arimathea in all of the Gospel accounts (but not in 1 Corinthians 15:4, curiously enough). But even on Dr. Magness’ proposal, Jesus’ body wouldn’t have been placed in a new tomb where no-one had ever been laid, as the Gospels narrate, but at best, inside a new niche within Joseph’s family tomb, which would have already held lots of bodies.

Confronted with this evidence, any prudent and unbiased historian would have to conclude that if Jesus was buried at all, it was most likely a dishonorable burial with no mourners, in which Jesus’ body was either buried in a trench grave with other criminals, or placed in temporary storage in Joseph of Arimathea’s family tomb, along with the bodies of Joseph’s family members. Not only is this picture at odds with the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ burial, but it also undercuts the apologetic case for the empty tomb. In particular, the oft-repeated apologetic argument that if Jesus’ tomb wasn’t empty, Jesus’ enemies would have had no trouble in producing his body and discrediting the apostles’ claims that Jesus had risen, turns out to be totally bogus: according to Jewish religious law, corpses were deemed to be no longer legally identifiable with any certainty if they were more than three days old (see here). The apostles didn’t start publicly preaching Jesus’ Resurrection until seven weeks after the Crucifixion – by which time, even if Jesus’ corpse had still been lying in a tomb, nobody would have been able to positively identify it, anyway.

That brings us to the New Testament accounts of the risen Jesus’ appearances to his disciples, as well as his brother James and Saul of Tarsus, an early persecutor of Christianity. There are about eleven recorded appearances, and in his book, Alter manages to uncover contradictions in nearly all of them, which I’ll discuss in Section D below. For the time being, all I’ll say is that Alter’s book uncovers a lot more contradictions than one might expect, as well as some gaping holes in the Gospel narratives. I would also like to thank Matthew Ferguson for his article, Reply to Vincent Torley (April 12, 2017), written in response to my OP, Evidence for the Resurrection (The Skeptical Zone, April 4, 2017). Ferguson’s article had a strong influence over my thinking, as it made a number of telling points. Ferguson’s and Alter’s most telling points regarding the Resurrection narratives are summarized in Section B below, and presented in much greater depth in Section D.

“Whoa! Holes in the Resurrection narratives?” the reader may be asking. “What holes?” Fair question. How about these ones: first of all, why did the women go to Jesus’ tomb on Easter Sunday morning? Was it simply to visit Jesus’ body, as in Matthew and John, or to anoint the body, as in Mark? And why did they travel in the dark, before dawn, without a male to accompany them? (Not a wise thing to do, back in the first century A.D.) And how did they plan to roll back the “very large” stone at the entrance to the tomb, recorded by Mark? (Breaking into a private tomb was a crime punishable by exile under Roman law, so no passersby would have helped them.) And why would the women have gone to anoint Jesus’ dead body on Easter Sunday morning, as Mark records, if they were then going to rewrap it in dirty linen cloths afterwards? That really doesn’t make sense.

But the key point that we need to bear in mind here is that in order for an appearance of Jesus to serve as good evidence for his Resurrection, it would have to be multiply attested by witnesses whose testimonies were mutually consistent, and it would have to involve them not only seeing and hearing Jesus (as one might in a vision) but experiencing physical contact with him. As I will demonstrate in detail in Section D, the Biblical narratives of Jesus’ Resurrection appearances turn out to be highly inconsistent. If we examine the Gospel narratives of Jesus’ appearances to his apostles, for instance, we find that they contradict each other on the most basic details: who saw Jesus (was it ten, eleven or twelve apostles?), when they first saw him (Easter Sunday evening, as in Luke and John, or a few days later, as in Matthew?), and where they saw him (only in Jerusalem, as in Luke, or not until they had returned to Galilee, as in Mark and Matthew?) Additionally, most of the Resurrection appearances recorded in the New Testament fail to meet the criteria of multiple attestation and physical contact: some (like those to James and Paul) were to only one individual, while others fail to record the disciples having any physical contact with Jesus (which would rule out the hypothesis that they were having a vision, say).

An artist’s impression of a black triangle UFO. Image courtesy of Skeezerpumba and Wikipedia. If several people claimed to have seen an object like this one, investigators would want to verify that their accounts tallied. What if they claimed to have seen a man who had risen from the dead?

To be sure, there are a few accounts in the Gospels, where Jesus appears to and has physical contact with multiple individuals. Unfortunately, however, these Gospel accounts don’t contain any eyewitness interviews, so we have no way of knowing whether the various witnesses to Jesus’ Resurrection all saw, heard and felt the same thing on the occasions when they collectively encountered him. Think about it: if a dozen people claimed to have seen a UFO land on Earth, one would surely demand to see transcripts of separate interviews with each witness, and/or diagrams of what each witness saw, just to make sure that their reports tallied with one another. The same goes for modern-day Marian apparitions, such as Fatima and Medjugorje: as a routine matter, Church-appointed investigators of these visions attempt to establish whether the seers are all seeing and hearing the same thing. (Tactile apparitions are much rarer, but they have occurred.)

The best argument that Christian apologists can marshal in response to this objection is that the disciples must have all experienced the same thing, or otherwise they wouldn’t have all been prepared to die for their faith in Jesus’ Resurrection: only if they had carefully checked out each other’s accounts of what they experienced and found that they all tallied would they have acquired the courage to lay down their lives for their faith in Jesus. But that’s a psychological assumption: nowhere does the New Testament claim that the disciples cross-checked their experiences with one another. (Incidentally, the Fatima seers, who remained steadfast even after being threatened with torture and death in August 1917, didn’t all see or hear the same thing, as we can tell by examining Dr. Formigao’s interviews with each of them, regarding what they witnessed at the Fatima miracle of October 13th, 1917: their accounts are quite divergent.) A skeptic might also point out that only two of the twelve apostles are known to have been put to death, and that in any case, we don’t know whether they were executed on account of their faith in Jesus’ Resurrection, or for some other theological or political reason, as Michael Alter suggested in a radio debate with Jonathan McClatchie (March 28th, 2016) – see the segment from 1:05:00 to 1:06:20. But even if the apostles were martyred for their faith in the Resurrection, the foregoing argument overlooks the possibility that many of the apostles may have only seen Jesus, while a smaller number (say, Peter, James, John and Thomas) not only saw but heard him, and an even smaller number (say, Thomas alone) actually touched him. The apostles may have all seen the same thing (more or less), but without hearing or feeling the same thing. We just don’t know. However, in order to prove a resurrection (as opposed to an objective vision sent by God), one would need to establish that several of the disciples not only saw and heard Jesus, but made physical contact with him as well. The upshot of all this is that the Resurrection accounts would never pass muster in a court of law: there are too many holes in the stories, and they don’t meet standards of good evidence. No impartial historian would find them convincing evidence for Jesus’ Resurrection.

In short: Alter’s book does a brilliant job of eviscerating the apologists’ case for the high probability of the Resurrection. Whether one chooses to continue believing it (as I do) or not, one is forced to accept, after reading the book, that belief in the Resurrection cannot be built on the foundation of historical data, for it is a foundation of sand.

My Executive Summary ends here. Some readers may wish to stop at this point, but I would urge those who are not too pressed for time to navigate their way around the main menu below. I would particularly urge readers to peruse Section A, which contains my own critical comments on Michael Alter’s book. For those readers who wish to continue beyond that point, there are two options: they may either read Section C and Section D (which deal in detail with Jesus’ Crucifixion and Resurrection, respectively) or they may read Section B, which is a short summary of sections C and D. For those readers who like to explore issues in depth, Section E contains three detailed case studies, which establish beyond reasonable doubt that the Gospel accounts are mutually contradictory and inconsistent with known facts. Finally, Section F traces the history of the passion and resurrection narratives. Interestingly, it turns out that we can reconstruct a “core narrative” which is mostly accurate.

==========================================================

A. MY OWN COMMENTS ON MICHAEL ALTER’S BOOK

How has Alter’s book impacted my own faith?

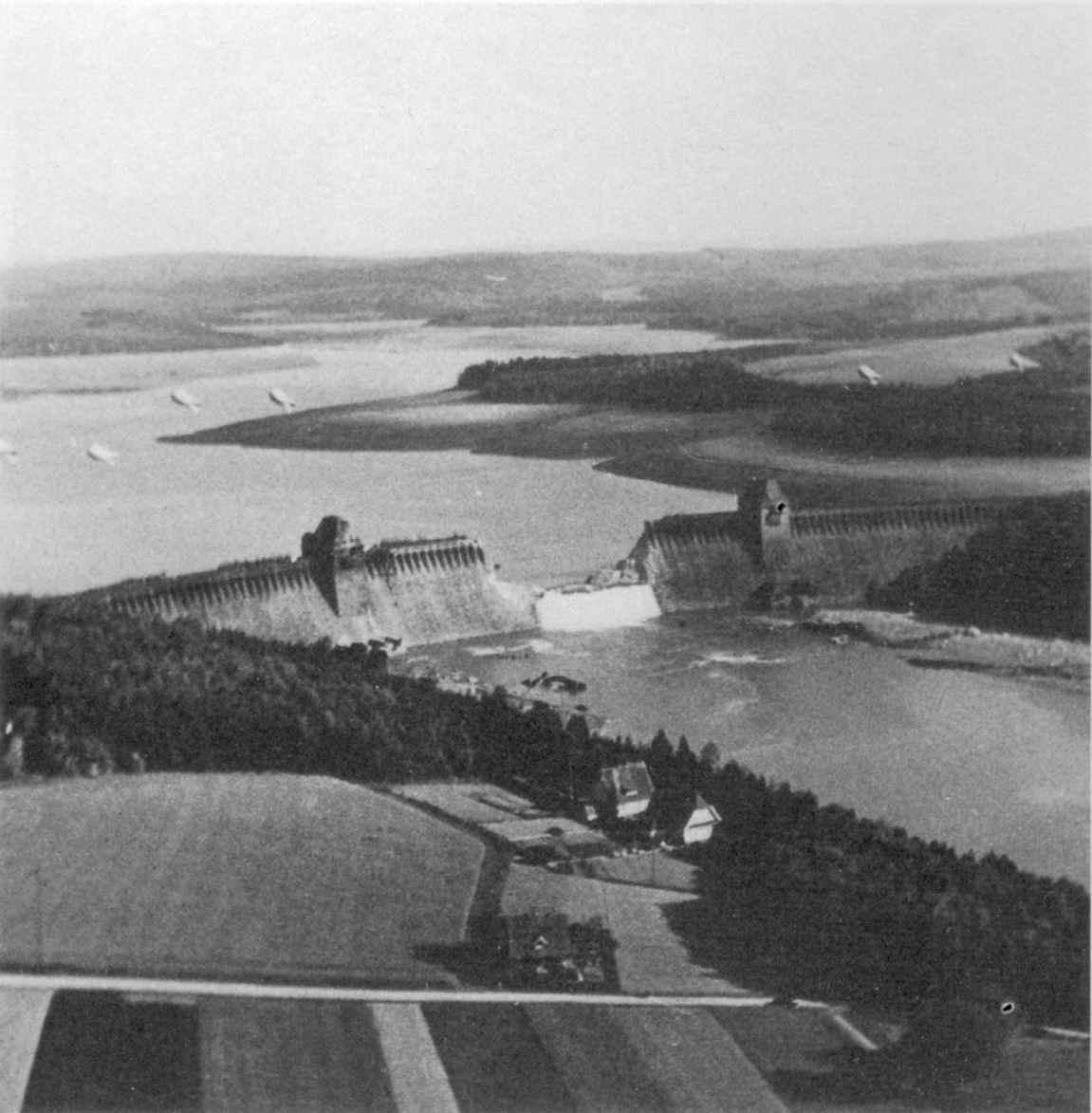

Photograph of the breached Möhne Dam taken by Flying Officer Jerry Fray of No. 542 Squadron from his Spitfire PR IX, six Barrage balloons are above the dam. Public domain. Image courtesy of Flying Officer Jerry Fray RAF and Wikipedia.

A few years ago, I purchased a book on the evidence for the Resurrection written by a homicide detective who used to be a diehard atheist, and was now an ardent believer. Jim Warner Wallace’s Cold Case Christianity was described by leading apologist Gregory Koukl as “simply the most clever and compelling defense I’ve ever read for the reliability of the New Testament record. Case closed.” And indeed, it was a very convincing book, whose arguments were presented in a way that was both arresting and devastatingly logical. More recently, I purchased another book on the Resurrection, titled, Did Jesus Really Rise from the Dead?, written by Dr. Thomas Miller, a distinguished surgeon with more than 200 scientific papers to his name, who was also the editor of three textbooks on surgical physiology. Miller’s book was touted by Dr. Bruce MacFayden, a professor of surgery, as “a ‘must read’ for those who are searching for truth and a logical, unbiased evaluation of the facts concerning the physical resurrection of Jesus.”

Neither of these brilliant books can hold a candle to Michael Alter’s demolition job on the Resurrection. Alter’s book attacks the case for the Resurrection at its Achilles’ heel: the historical reliability of the Gospels – a subject with which Alter is intimately familiar.

For me, reading Alter’s book was the intellectual equivalent of a “Dambusters” bomb going off in my head: the case it made was so strong that it shattered my psychological defenses and forced me to revise my own theological views. Prior to reading the book, I was quite happy to take up cudgels in defense of the historical accuracy of the Bible. After reading the book, I am now far more skeptical of the Bible’s historical reliability than I was previously, and I no longer hold rigidly to any doctrine of Biblical inerrancy. Instead, my predominant feeling now is one of utter detachment: “Let the chips fall where they may.”

The reason why Alter’s book has forced a theological rethink on my part is that it deals with a period in history when the facts are checkable. It is very difficult to check the accuracy of the Bible when it narrates events that allegedly occurred in the distant past. For example, historians can neither prove nor disprove the assertion that a man named Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt over 3,000 years ago, or that the ten plagues of Egypt were historical events. (It is of course easy to show that the Israelites of the Exodus could never have numbered two million people, but it’s equally easy to point to passages in the Bible which suggest that they only numbered about 20,000 people, which is historically feasible. See here and here.) Going further back in time, uncertainties regarding both the literary genre of Scripture and the meaning of the words used combine to make it even harder to assess the Bible’s factual reliability. Did the Flood described in Genesis cover all the Earth, or merely all of the land in the Mesopotamian region? The Hebrew wording is ambiguous. And were the writers of Genesis 6 to 8 intending to compose a historical narrative of an event that occurred thousands of years previously, or were they simply adapting a pre-existing, commonly accepted Babylonian folktale about the gods destroying most of the human race by sending a Deluge into a theological narrative which instead depicts the Flood as a punishment from Almighty God, without questioning whether it actually occurred? Who can say?

But there can be no doubt that the writers of the New Testament intended to assert that a man named Jesus lived, died and was raised from the dead, during the time when Pontius Pilate was prefect of Judea. And it is far easier for historians to check the factual accuracy of these writers’ statements about Jesus’ arrest, trial, crucifixion and burial than it is for Eqyptologists to verify what the book of Exodus says about the life of Moses. Additionally, the four Gospels exhibit a relatively high degree of agreement in their narratives of Jesus’ final days, making it an ideal litmus test of the Bible’s historical accuracy.

Back in the early 1980s, when I first came across skeptical challenges to the reliability of the Gospel narratives of Jesus’ arrest, trial, crucifixion and burial, I was mildly troubled by them, but not unduly so. It seemed to me that the skeptics were trying to put a full stop where history left a comma. The Gospel accounts of Jesus’ trial, for instance, were wildly at variance with trial procedures laid down in the Mishnah – but then, the Mishnah was composed in the second century, not the first, when Jewish oral traditions were being codified for the first time. Perhaps there was greater laxity in legal procedures, in Jesus’ day – and perhaps also, the chief priests were so desperate to get rid of Jesus (“Better that one man should die for the people…”) that they were willing to bend a few rules in the process. And while I was aware that the Evangelists’ depiction of Pilate as being reluctant to convict Jesus did not accord with contemporary Jewish accounts of his savage cruelty, I was also willing to allow that Pilate may have been reluctant to sentence Jesus to death because he had a superstitious fear of him, having heard about the miracles he had wrought. In short: my faith was rocked, but not shattered, by New Testament criticism. (When I later came to reject the Christian faith in 1989, it was principally for philosophical reasons, and not because of historical errors in the Bible. It would be another fifteen years before I was able to resolve my philosophical doubts and return to the faith. But that’s a story for another day.)

There was one book I encountered in the 1980s which could have – and should have – set me straight on the reliability of Scripture: Fr. Raymond Brown’s The Birth of the Messiah. Fr. Brown accepted the virginal conception of Jesus (as I still do) but maintained that he was probably born in Nazareth, and that the Infancy narratives in Matthew’s and Luke’s Gospels were based on popular traditions but were not historical. When I read Brown’s book, I resisted its conclusions, because it seemed to me that he had not proven his case. In other words, I was willing to give the Biblical authors the benefit of the doubt.

House of cards. Image courtesy of Floppydog66 and Wikipedia.

No more. I have changed my mind for three reasons. First, I have come to see that I was asking the wrong question. The question which a Christian reading the Gospels should ask is not, “Are there any knockdown arguments against the historical accuracy of the Gospels?” but rather, “Would an impartial historian, reading the Gospels, conclude that they probably contained factual errors which call into question their reliability?” I’d like to give John Loftus credit for this change in my thinking: although I reject his famous Outsider Test for Faith, as it leaves no room for the sensus divinitatis, I do accept an Outsider Test for Apologetics: in other words, you shouldn’t try to convince a skeptic of the truth of some historical claim unless you’re confident that your argument would also convince a fair-minded historian in that field. And when we are discussing the Resurrection, the question we need to ask is: “Would an impartial historian, reading the Passion and Resurrection narratives in the Gospels, be inclined to dispute their factual reliability?” If the answer is “Yes,” then Christians should not appeal to these narratives, when trying to persuade skeptics that the Resurrection occurred. Simple as that. And if it turns out that an impartial historian would query even the set of “minimal facts” employed by Habermas and Licona, then the entire enterprise of arguing for the Resurrection on historical grounds collapses like a house of cards.

The Resurrection is the pivotal miracle on which the apologetic case for Christianity stands or falls. An apologist who has already made a powerful case for the Resurrection and for the overall historical reliability of the New Testament can go on to argue that other miracles recorded in the Gospels – such as the virginal conception of Jesus – for which the historical evidence is far weaker than for the Resurrection, should nevertheless be treated as factual occurrences, because we can trust what the New Testament says, if its central claim is correct. (Such an argument is at least plausible, whatever one may think of it.) But it would be circular reasoning if the apologist were to argue for the Resurrection itself in such a fashion. The evidence for the Resurrection has to be strong enough to convince an open-minded outsider. There can be no special pleading here, when attempting to smooth over difficulties in the narratives. Instead, the question one constantly needs to keep in mind is: what would a hardnosed but fair-minded skeptic say?

A powder snow avalanche in the Himalayas near Mount Everest. Image courtesy of Chagai and Wikipedia.

The second consideration that changed my mind was the mountain of facts assembled by Alter in his book, which hit me like an avalanche when reading it. The case Alter assembles is so overwhelming as to leave any honest inquirer with no reasonable doubt that the New Testament makes statements about Jesus which are not only mutually contradictory but also demonstrably wrong – at least, as far as historians can tell. I now take a much more modest view of the Bible’s reliability in historical matters, and I’m quite happy to concede that on many occasions, the Evangelists “got it wrong.” I continue to believe in the Resurrection, for reasons that have more to do with the heart than the head. The character of Christ reveals him to be a figure who is larger than life itself. On this point, I can do no better than to quote Beverley Nichols’ matchless prose, taken from his work, The Fool Hath Said (Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc.; Garden City, New York: 1936):

You cannot deny the reality of this character, in whatever body it resided. Even if we were to grant the professor’s theory that it is all a hotchpotch of legend, somebody said, ‘The Sabbath was made for man, and not man for the Sabbath’; somebody said, ‘For what shall it profit a man if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul’; somebody said, ‘Suffer the little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for of such is the Kingdom of God’; somebody said, ‘How hardly shall they that have riches enter into the Kingdom of God’; somebody said, ‘All they that take the sword shall perish with the sword.’

Somebody said these things, because they are staring me in the face at this moment from the Bible. And whoever said them was gigantic. And whoever said them was living, because we are in the year 1936, and I am ‘modern’, and you are ‘modern’, and we both of us like going to the cinema and driving a car, and all that sort of thing, and yet we cannot find in any contemporary literature any phrases which have a shadow of the beauty, the truth, the individuality, nor the indestructibility of those phrases. (1936, pp. 103-104)

Additionally, I have to say that I find the idea of God becoming incarnate appealing and I consider Jesus a worthy candidate for God incarnate, after reading about his teachings, his impact on the lives of his disciples, and the way in which the Christian faith totally transformed the Roman world and gave rise to modern Western civilization. And finally, I’m still inclined to think that a post-mortem physical encounter with Jesus is the best explanation for his disciples’ bizarre claim that he was not merely alive, but had risen from the dead. But I would no longer argue on historical grounds that the conviction of Jesus’ disciples that their Master had risen from the dead, coupled with what we know about Jesus’ death and burial, makes the Resurrection highly probable. There are far too many unknowns for us to reach such a conclusion today.

The third and final reason that led me to change my mind was Alter’s seemingly effortless ability to cut down arguments put forward by leading Christian apologists. For example, one constantly hears the argument (which I discussed briefly above) that the tomb of Jesus must have been empty, otherwise the chief priests would have had no problem in producing Jesus’ dead body. What one never hears is that the apostles didn’t begin preaching the Gospel until seven weeks after the Crucifixion – by which time, the body of Jesus would no longer have been identifiable for legal purposes, even if it had still been in its tomb. For the Jews, the third day was the point beyond which the ravages of decay were said to render faces of corpses incapable of being legally identified with certainty in a court of law. To quote the words of The Mishnah (Yevamot, Chapter 16, Mishnah 3, sections 1-3), which provides a list of rules of what a witness needs to see in order to testify that someone is dead: “They are allowed to testify only about the face with the nose, even though there were also marks on the man’s body or clothing. They are allowed to testify only when his soul has departed, even though they have seen him cut up or crucified or being devoured by a wild beast. They are allowed to testify only [if they saw the body] within three days [of death].” As Dr. Joshua Kulp explains in his commentary: “A person is identifiable only through his face and his nose. Therefore, if someone sees other parts of his body or face, but not his face and nose, he cannot testify that the person is dead… The witness must testify within three days of the death. Otherwise the body may begin to decompose and identity cannot be provided with certainty.” That’s the kind of “inside knowledge” that you’ll find in Alter’s book: it’s written from a distinctively Jewish perspective.

Or to take another example, it is common for Christian apologists to argue that St. Paul’s reference to Jesus being seen by 500 people, some of whom were still living (see 1 Corinthians 15:6) must be factually true, as the Corinthians could easily have sent a delegation to Jerusalem to verify his claim. But as Alter points out (2015, pp. 671-673), there was no real likelihood of this ever happening: a trip from Corinth to Jerusalem would have been costly in terms of time and money, as well as being hazardous to the travelers’ physical safety. And having arrived in Jerusalem, how would a traveler go about locating these 500 people, without knowing any of their names?

Alter is especially skillful when rebutting apologetic arguments that apparent contradictions in the Gospels are like multiple eyewitness reports of a car accident, and that the different accounts are not contradictory but complementary, like separate pieces of a jigsaw puzzle: as he points out (2015, pp. 27, 123), most of the Evangelists weren’t eyewitnesses, so what they were reporting was hearsay, based on recollections and evolving oral traditions which were written down decades after the events occurred. In any case, the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ Resurrection appearances don’t dovetail one another nicely: rather, the problem is that they simply don’t fit together. One can force them to fit, after a fashion, but only by making lots of ad hoc assumptions.

The “minimal facts” approach to the Resurrection

Three-legged stool. Image courtesy of Sebastien Rivory and Wikipedia.

At the present time, the most popular Christian method of arguing for the reality of the Resurrection is the “minimal facts” approach, advocated by Gary Habermas and Mike Licona, which attempts to build a case for the Resurrection on the basis of historical facts about Jesus which are generally accepted by scholars of all religious persuasions and none. These agreed facts may be likened to a three-legged stool, supporting the case for the Resurrection. Briefly, they are as follows: (i) Jesus was crucified, died, and was buried, and some time afterwards, his tomb was found empty; (ii) Jesus’ disciples, as well as his brother (or half-brother) James and the anti-Christian Saul of Tarsus, had experiences in which Jesus appeared to them after his death; and (iii) these appearances led to their conviction that Jesus had been raised by God from the dead. (James and Paul’s conversions are often listed as separate facts [see here, for instance], but I’ve lumped them in with those of the disciples here.) On this approach, the details of the risen Jesus’ appearances to his disciples in the New Testament are ignored: all that matters is that Jesus’ disciples saw him, spoke to him and had some sort of physical contact with him. St. Paul is these apologists’ chief source of evidence for the Resurrection; the Gospel accounts receive scant attention. (Contrary to popular belief, Dr. William Lane Craig is not a “minimal facts” advocate: his approach incorporates material from the Gospels, whereas that of Professor Gary Habermas and Dr. Mike Licona relies exclusively on St. Paul’s writings. See here.)

I was at one time highly impressed with the “minimal facts” approach. However, this approach relies heavily upon the historicity of the empty tomb, and after reading Michael Alter’s book, I am reluctantly persuaded that when the evidence is assessed on purely historical grounds, it appears highly doubtful whether Jesus’ tomb was found empty by his disciples, or even whether Jesus was buried in a tomb, let alone a new one that didn’t contain any other bodies. And I am even more persuaded that the “empty tomb” story in the Gospels is unlikely to be historical, after reading what Professor Bart Ehrman has written on the likely fate of Jesus’ body (see in particular his articles, Why Romans Crucified People and Did Romans Allow Jews to Bury Crucified Victims? Readers’ Mailbag January 1, 2018). To put it bluntly: the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ burial on Good Friday and of the women running to the tomb on Easter Sunday morning just don’t add up. As we have seen, the empty tomb is one of the “three legs” supporting the “minimal facts” case for Jesus’ Resurrection.

As an aside: I would argue that a Christian can still believe in Jesus’ bodily resurrection, without necessarily believing that Jesus was buried in a tomb. As a Christian, I am prepared to accept that Jesus “was buried” (in some fashion), as the oldest Christian creeds say he was, but more than that I will not affirm. As Ehrman’s article shows, even arguing for Jesus’ burial is fraught with historical difficulties.

Can a two-legged stool remain standing? Well, perhaps. A few “ultra-minimalists” would be prepared to jettison the empty tomb apologetic, and appeal to Jesus’ post-mortem appearances to his disciples as the decisive piece of evidence for the Resurrection. While the appearances themselves are not in doubt, it is impossible for the historian to argue for their objective reality, let alone their physicality, without solid evidence that Jesus’ disciples all saw, heard and felt the same thing (more or less), when Jesus appeared to them. Unfortunately, the Gospel accounts fail to provide that kind of evidence: they are lacking in detail, and don’t corroborate one another well. What that means is that historians today – even if they are open to the possibility of miracles – have no way of demonstrating that the Resurrection is certain beyond reasonable doubt, or even that it is more probable than not.

The “maximal data” approach to the Resurrection

A four-piece jigsaw puzzle. Image courtesy of Amada44 and Wikipedia.

In contrast with this “minimal facts” approach, other writers (notably Drs. Timothy and Lydia McGrew) have championed a “maximal data” approach, arguing that the Gospel accounts of the Resurrection reinforce one another, with details in one account

dovetailing neatly with the details in other accounts like pieces of a jigsaw. (See here and here.) On the “maximal data” approach, the Gospels are no longer regarded as documents written 40 to 60 years after Jesus’ death; instead they are viewed as either eyewitness reports of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection (e.g. John’s Gospel), or (in the case of the Synoptic Gospels written by Matthew, Mark and Luke) as biographical reports, written only 25 to 30 years after Jesus’ death, which are based on interviews with eyewitnesses who had personally known Jesus. Maximalists contend that the “minimal facts” approach falls short, on evidential grounds. They insist that without the detailed narratives of Jesus’ crucifixion, burial and resurrection found in the Gospels and in Acts, it is difficult for a Christian apologist to make a convincing case for Jesus’ resurrection from the dead: the very most that one could establish from St. Paul’s brief account in 1 Corinthians 15 (much beloved of the minimalists) is that the disciples had some sort of spiritual encounter with Jesus, after his death: maybe he appeared to them in a vision, but not as an embodied being. To argue for a resurrection, they say, we need the Gospel accounts – which means that we need to argue for the reliability of the Gospels. As Dr. Lydia McGrew puts it:

When the assertion that the disciples had appearance experiences is so weak that it is consistent with purely visionary experiences of an intangible Jesus, inaccessible to any but his followers, experiences that, for all that is stated to the contrary, might have been fairly brief, involving sight and no other senses, then it becomes a much, much harder task to argue that there must have been a supernatural explanation for what happened. It becomes harder still to argue that the correct explanation is that Jesus really was physically risen from the dead. I won’t go so far as to say that a minimal facts case thus construed provides no evidence for Jesus’ literal resurrection, but it is a much weaker case than a case that includes, as data indicating what the disciples claimed, the types of experiences actually recounted in the gospels. (See here.)

It is fair to ask how advocates of the two approaches go about establishing the high probability of the Jesus’ Resurrection. Apologists arguing for the “minimal facts” approach freely acknowledge the difficulty in calculating the prior probability of God miraculously raising Jesus from the dead, so they tend to rely on inference to the best explanation in order to demonstrate that the Resurrection is the only explanation that accounts for all of the relevant facts. “Maximal data” apologists, on the other hand, employ Bayesian logic to show that the Resurrection occurred. They argue that although the prior probability of the Resurrection is very low, the evidence of the Gospels increases the likelihood of the Resurrection to an enormous degree, such that in the light of this evidence, the posterior probability of the Resurrection is very close to 1. When explaining why the eyewitness evidence for the Resurrection boosts the odds so dramatically, these apologists argue that the combined probability of a dozen or so witnesses (the apostles) all seeing, hearing and feeling the same thing when they claimed to have met the risen Jesus would be vanishingly low if they were all hallucinating, whereas if Jesus really was appearing to them, this is precisely what we’d expect. These apologists then calculate the extent to which the apparitions of Jesus increase the probability of the Resurrection (from near-zero to almost one), by treating each apostle who saw Jesus as an independent witness, which then allows us to multiply the individual probabilities of each of them having the same hallucination. For instance, if the probability of one apostle (say, John) seeing, hearing and feeling the same thing as Simon Peter did when they had an apparition of Jesus is (say) only 1 in 1,000, and if there were ten other apostles (barring Judas Iscariot) who experienced the same thing as Peter did when he had an apparition of Jesus, then we can calculate the probability of them all having the same apparition by chance as (1 in 1,000) raised to the power of 10, or 1 in 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000. Odds like that pretty much rule out the hallucination hypothesis, unless you’re so biased against the supernatural that nothing would persuade you. (I would note in passing, however, that they do not rule out the “objective vision” hypothesis, which explains the Resurrection appearances as a post-mortem vision of Jesus sent by God, rather than a physical encounter with Jesus. This is a third hypothesis which deserves more attention, in my view. As I see it, the key point that tells against it is that it would have been much easier for the disciples to make this more modest claim – “Jesus’ spirit appeared to us!” – and yet they did not: they insisted that Jesus had been physically resurrected. But please don’t ask me to formulate that into a rigorous mathematical argument: frankly, I don’t think it can be done.)

To those who object to treating the apostles as independent witnesses, Drs. Tim and Lydia McGrew reply, in their online paper, The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, that since many of them remained steadfast in their faith even when threatened with torture and death, each must have had his own powerful, independent reasons for believing in the Resurrection – otherwise he would have capitulated and apostasized under duress:

If any one of the witnesses in question had not actually had clear and realistic sensory experiences just as if Jesus were physically present, talking with them, eating before them, offering to let them inspect his hands and side and the like, it is not credible that he would listen to the urging of his fellows to remain steadfast in testifying to such experiences. To paraphrase Samuel Johnson, the credible threat of death concentrates the mind wonderfully; it tends to winnow the wheat from the chaff when it comes to good and bad evidence.

In plain English: the apostles must have all independently experienced Jesus, and each of them must have had the same experience of their risen Master – otherwise, they wouldn’t have all been ready to suffer and die for him. Readers will note that this argument relies heavily on a psychological counterfactual about the conditions under which the apostles would have been ready to die for their belief in the Resurrection, coupled with the psychological assumption that the disciples would have all carefully compared notes about the details of their experience after Jesus appeared to them (maybe, but who knows?), plus two more factual assumptions: the historical assumption (which has been called into question by Professor Candida Moss in recent years) that the apostles were continually under threat of being tortured or martyred, and another historical assumption: namely, that the specific reason why they were martyred was that they believed in and preached the message that Jesus had risen from the dead. The case for the Resurrection is a solid one only if all four assumptions are true.

Probability, not possibility: the general flaw in the “maximal data” approach to Resurrection apologetics

But there is a more general flaw in the “maximal data” approach to Resurrection apologetics: contrary to what its advocates claim, the historical details in the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion, burial and resurrection don’t fit together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, but contradict one another wildly, as well as conflicting with known facts relating to first-century Palestine. There are literally dozens of problems with the Gospel accounts, as well as the accounts in Acts, which render them historically implausible and make them appear mutually contradictory: Alter lists no less than 120 contradictions in his book. I discuss these in Section C and Section D below.

Now for all I know, the historical difficulties with these accounts may all turn out to have a satisfactory resolution; however, historians don’t deal with what’s merely possible, but with what’s probable, in the light of the evidence. I believe that after weighing up these problems, an impartial historian would have no choice but to bet against the overall reliability of the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection, as they contain too much material which appears highly improbable, when assessed objectively – and no, I’m not talking about miracles, but about how key figures in the Gospel narratives – people like Pilate, the chief priests, the Roman soldiers who crucified Jesus, and the women who visited Jesus’ tomb – are supposed to have acted. If you want to defend the Gospel narratives, then you have to believe that all these people behaved in a way that was totally out of character for them, on numerous occasions, all within a very short span of time (less than 48 hours). A devout Christian might be prepared to believe that they did so, under the mysterious influence of God’s grace, but historians are not free to make such gratuitous assumptions, any more than they are free to invoke “Jedi mind tricks” when explaining why certain historical individuals acted in the way they did. That’s ad hoc argumentation. The “maximal data” case for the Resurrection thus dies the death of a thousand cuts.

Why we need an incident-by-incident approach to Gospel reliability

Ross Wilson’s statue of C. S. Lewis in front of the wardrobe from his book The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in East Belfast. While not a believer in Biblical inerrancy, Lewis was a staunch defender of the reliability of the Gospels. Image courtesy of Genvesssel and Wikipedia.

Or does it? In a recent blog article on the historicity of John’s Gospel, “maximal data” advocate Dr. Lydia McGrew writes:

The incident-by-incident approach to Gospel reliability is wrong. Dead wrong. Philosophically wrong. Epistemologically wrong. Historically wrong. When one has evidence for the historical nature and intention of a Gospel overall (as we do have for John), then the specific incidents in it do not need to be individually defended, starting each time from a position of agnosticism, on a case-by-case basis.

Needless to say, I strongly disagree with this assessment. I’d like to explain why, with reference to John’s Gospel, which could be fairly described as the most polarizing of all the Gospels: it has its vocal defenders (see also here) and its equally vocal critics (see also here and here). To be sure, there is abundant textual evidence, which is handily summarized in chapter 19 of Oxford Professor Rev. William Sanday’s career-launching academic bestseller, The Authorship and Historical Character of the Fourth Gospel (London: Macmillan, 1872), that John’s Gospel was written by a Jew who was thoroughly familiar with the geography of Palestine, and with the customs of its first-century Jewish inhabitants. By itself, however, that merely shows John’s Gospel to be authentic, without guaranteeing its historical reliability. Louis L’Amour, the acclaimed author of Western novels, often made a point of visiting the places that he wrote about, so that he could describe them accurately in his stories, but that does not make his stories true.

Unlike Louis L’Amour, the author of John’s Gospel clearly intends to write a historical biography of a real person, based on what he declares to be eyewitness testimony (John 19:35, 21:24). Professor Sanday makes a strong case that the author of John’s Gospel either personally witnessed many of the events which he narrates in his Gospel, or had access to people who did. I would also recommend Dr. Cornelis Bennema’s carefully argued article, The Historical Reliability of the Gospel of John (Foundations, No.67 Autumn 2014). The literary style of John’s Gospel has also captivated many readers – notably C. S. Lewis (pictured above), a professor of literature at Magdalen College, Oxford, who wrote in his essay, “Modern Theology and Biblical Criticism”: “Of this text there are only two possible views. Either this is reportage — though it may no doubt contain errors — pretty close up to the facts; nearly as close as Boswell. Or else, some unknown writer in the second century, without known predecessors or successors, suddenly anticipated the whole technique of modern, novelistic, realistic narrative.”

But the fact that John’s Gospel contains accurate reporting of the facts does not guarantee its historical reliability throughout. To begin with, the Gospel makes no pretense of being an objective account; it was written for an avowedly propagandistic purpose: “so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name” (John 20:31). Moreover, factual reporting takes up only a small percentage of John’s Gospel: most of it consists of either discourses uttered by Jesus or dialogues between Jesus and his interlocutors (who are often mysteriously described as “the Jews.”) These discourses and dialogues were not committed to writing until several decades after Jesus’ death. Professor Sanday freely acknowledges the difficulty of disentangling what was actually said from the Evangelist’s personal interpretation of Jesus’ words, in his chapter on Jesus’ last discourse: as he puts it, “it is impossible for an active mind to retain the exact recollection of words over a space of perhaps fifty years” (p. 222) and he adds that a strong mind and character (like that of the author of John’s Gospel) “is much less likely to retain a faithful recollection of words than a weak one. Its natural impulse is to creation” (p. 223). Sanday concludes: “We shall then renounce the attempt to discriminate closely between the subjective and objective elements in this parting discourse” (1872, p. 223).

And that brings me to my next point: the material we have in John’s Gospel is colored through the lens of sixty years of theological reflection. Personally, I have no difficulty in believing that many of the “I am” statements ascribed to Jesus in the Gospel are authentic in their kernel, at least: “I am the bread of life,” “I am the door,” “I am the good shepherd” and “I am the vine.” But “Before Abraham was, I am” (John 8:58) is such a brazen claim to divinity that if it had been made, Jesus’ trial before the Jewish Sanhedrin on a charge of blasphemy would have been over in about two minutes; and no less a personage than the former Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury, Michael Ramsey, who was himself a New Testament scholar, has acknowledged that during his lifetime, “Jesus did not claim divinity for himself.” That way of viewing Jesus came later.

An additional point which tells against the historicity of John’s Gospel is the divergence in style between John and the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke). In the words of the late Professor Maurice Casey: “These differences are so extreme that both cannot be right.” (Is John’s Gospel True?, 1996, London: Routledge, p. 80). We are not talking here about John merely rewriting the content of Jesus’ speeches in his own fashion; rather, what we find is that there is almost no overlap in content, or even in theme, between the teachings of Jesus recorded in the Synoptics and John’s record of Jesus’ teachings. Words such as “preach,” “repent,” “repentance,” “sinners,” “tax collectors” and “scribe,” common in the Synoptics, are absent or virtually absent from John’s Gospel, as is the word “parable.” The word “kingdom,” mentioned 57 times in Matthew, 20 times in Mark and 46 times in Luke, occurs a paltry five times in John. On the other hand, words like “love,” “true,” “truth,” “light,” “reveal,” “believe,” “scripture,” “Father,” “Son” and “witness” are far more common in John than in the Synoptics. Scholars such as Richard Bauckham have argued that Jesus’ aphorisms and parables, recorded in the Synoptic Gospels, were “the carefully composed distillations of his teaching, put into memorable form for hearers to take away with them,” whereas John more realistically depicts Jesus as speaking in longer discourses and dialogues. Undoubtedly the Synoptic Gospels are a distillation, but they are not a distillation of John, whose account of Jesus’ teaching is very different in its content. Defenders of the historicity of John need to explain this striking divergence.

A final point which the apologists for John’s Gospel often pass over is the question of who the “Beloved disciple” was. The question matters, because it is his testimony that we rely on for such intimate scenes as the Last Supper, the interrogation of Jesus by the High Priest (who knew the Beloved disciple – see John 18:15), the two disciples’ race to the tomb of Jesus on Easter Sunday morning, and the vivid account of the risen Jesus appearing to his disciples by the Sea of Tiberias and telling Peter how he would one day be martyred. Who is this disciple? Traditionalists tend to favor John son of Zebedee, while a few scholars, including Dr. Richard Bauckham, argue that it was a well-connected Jerusalem disciple of Jesus, known in antiquity as John the Elder. But as Dr. Cornelis Bennema acknowledges in his above-cited article, both views face severe difficulties: “It is difficult to imagine that the Galilean fisherman John of Zebedee had such connections in Jerusalem (unless he had a retail outlet in Jerusalem that supplied fish to the high priest). However, it is equally difficult to imagine that John the Elder was present at the private Farewell Discourses and even had a closer relationship with Jesus than any of the Twelve (13:23).” Interestingly, conservative scholar Dr. Ben Witherington suggests that the Beloved disciple was actually Lazarus, the man Jesus raised from the dead! At the same time, Witherington makes a very strong case that he could not have been John son of Zebedee. I would argue that until we can settle the question of the Beloved disciple’s identity, we are unable to settle the question of the Fourth Gospel’s reliability.

To sum up: given that John’s Gospel is a propagandistic work, which is heavily colored by its author’s theological views, and that we do not even know who its author was, we are not entitled to conclude that it is historically reliable; all we can say is that it contains many nuggets of historical fact, overlain by several decades of theologizing. The Synoptic Gospels, although written somewhat earlier than John’s, were still composed 30 to 50 years after Jesus’ death, and there is widespread scholarly disagreement (see here and here) as to whether the traditions concerning their authorship are reliable. (Almost nobody now thinks that the apostle Matthew wrote the Gospel that bears his name.) And in many ways, the Synoptics lack the intimate familiarity with Palestine that the author of John’s Gospel had – not to mention the little details that one only finds in John (e.g. “The servant’s name was Malchus” [John 18:10]), which impart such an air of verisimilitude to that Gospel. Finally, the Synoptic Gospels were also written for evangelistic purposes: Luke’s Gospel, which is addressed to a believer named Theophilus, was written in order “that you may have certainty concerning the things you have been taught” (Luke 1:4). That being the case, we can no longer argue for any Gospel’s historical reliability by simply appealing to “the historical nature and intention of a Gospel overall” (to quote Dr. McGrew’s words): instead, we have no choice but to go through a painful process of sifting, incident by incident, to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Thus if we find that the various Gospel accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion and burial contain well over a dozen statements which turn out to be historically doubtful, when examined on an incident-by-incident basis, we have no right to minimize these problematic statements as mere difficulties, on the grounds that we already know that the Gospels are historically reliable overall. We don’t know that.

Deceit in the Gospel narratives?

Pinocchio by Enrico Mazzanti (1852-1910) – the first illustrator (1883) of Le avventure di Pinocchio. Public domain. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Alter’s book makes an overwhelming cumulative case that the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ life are highly flawed historical narratives which contradict one another, as well as containing numerous factual errors which are at odds with Jewish and Roman customs. In addition, he reveals how the Gospels embellish historical events and even incorporate legendary accounts that were fabricated some decades after Jesus’ death.

Does this mean that St. Paul and the Evangelists are guilty of “making up stuff”? Alter evidently thinks so: in one of his speculations (#165), he cites examples of what he calls “Paul’s pious fraud,” in an attempt to demonstrate that the Christian Scriptures permit the use of deceit, in order to win converts and gain souls. But the evidence for this “fraud” in the New Testament consists of just three verses, none of which has anything to do with deception: Romans 3:7-8 (in which St. Paul rejects as “slanderous” the charge that Christians approve of doing evil that good may come); 1 Corinthians 9:20-23 (in which St. Paul declares, “I have become all things to all people, that by all means I might save some,” referring to his practice of accommodating his observance of the Jewish Law to suit the preferences of people he was trying to convert); and Philippians 1:18 (where St. Paul writes that he doesn’t care about the personal motives of missionaries in preaching the Gospels, so long as it gets preached – which is not a case of deceit, as it does not relate to what is preached, but merely to the reason why it is being preached). None of these are examples of “making up stuff.” St. Paul’s own feelings about the importance of truthfulness when evangelizing should be abundantly evident from the following passage: “As we have said before, so now I say again: If anyone is preaching to you a gospel contrary to the one you received, let him be accursed” (Galatians 1:9).

So, if deceit does not explain the tall stories we find in the Gospels, then what does? A more charitable hypothesis is that the Evangelists were overly credulous, and sometimes failed to distinguish facts from embellishments, when interviewing people about events they claimed to have witnessed in Jesus’ life. Additionally, they may have occasionally included certain popular stories about Jesus, precisely because they sounded like things that he would have done, despite the fact that there was no solid eyewitness testimony to corroborate these stories. That’s not lying, though it could fairly be described as gullible reporting.

But what about the legendary accretions found in all four Gospels (especially Matthew’s Gospel)? Surely these are outright fabrications? Not necessarily. In fact, many of these accretions seem to be loosely based on certain passages in the Old Testament. The Evangelists may have treated these passages as prophetic confirmation that the events described therein really took place in the life of Jesus. That assumes, of course, that these Old Testament passages were originally written about Jesus. But after reading Alter’s brilliant and devastating rebuttal of the “argument from prophecy,” much beloved of Christian apologists, I can only conclude that first-century Christians must have had a very peculiar (and highly creative) way of doing exegesis, as they apparently believed that these Biblical passages were indeed referring to Jesus. They seem to have envisaged Scripture as a multi-layered message: a passage that may appear to refer to a historical individual X when taken superficially, might also have a deeper and much richer meaning which refers to another, more recent individual, Y. However, I have to say that this way of interpreting Scripture sounds highly speculative to me, and I am not at all surprised that devout Jews would reject it, root and branch: had I been living in Palestine in the first century A.D., I’m sure I would have done the same.

There is, however, one troubling set of Gospel passages which do appear to be deceitful. I’m referring here to episodes narrated by the Beloved disciple in John’s Gospel, who claims to have personally witnessed them. As we saw above, it is almost certain, historically speaking, that Jesus’ mother and the Beloved disciple did not stand at the foot of the Cross, and that the story of blood and water flowing from Jesus’ side after he was pierced with a soldier’s lance is fictional. That being the case, why does the Gospel include these episodes which could never have taken place, with the express assurance that they were seen by an eyewitness who “knows that he is telling the truth” (John 19:35)? I ask this question out of genuine perplexity: I feel torn between the air of verisimilitude in John’s reporting these events, and the near-certain knowledge that they couldn’t have happened.