If the Aristotelian argument for a purely actual Being (which I critiqued in my previous post) is the backbone of Feser’s five proofs of God’s existence, the Thomistic proof is the beating heart, as it gets to the very core of what God is: Pure Existence itself, according to philosophy Professor Edward Feser. Today, I’m going to argue that this notion of God is utterly nonsensical. But it is not merely the argument’s conclusion which is flawed: the Thomistic proof also rests on shaky foundations, as the real distinction it posits between a finite thing’s essence and its existence is a highly dubious one: the main argument cited in support of it actually points to a matter-form distinction, instead. The second argument for a real distinction between a thing’s essence and its existence establishes nothing of the sort: all it shows is that whatever causes a thing to have existence also causes the nature or essence of that thing. A third argument for the essence-existence distinction illicitly assumes that the term “existence” names a single perfection, which is inherently simple and unlimited.

In addition, Feser’s Thomistic proof trades on an equivocation between the notion of a Being whose essence is identical to its own existence and that of a Being whose essence is Pure Existence – an equivocation which is grounded in the background metaphysical assumption that the concept of “existence” is a simple and unlimited one. In reality, as I shall explain below, the concept of “existence” is neither simple nor complex, neither limited nor unlimited, but rather, indefinite – which is one reason why the attempt to characterize God as Pure Existence, or Being itself, is doomed at the outset. Finally, any attempt to construe God as some sort of activity – whether it be Pure Existence, Pure Actuality, or Thought thinking Itself, or Love loving Himself – is radically mistaken, either because it reifies an abstraction (Existence exists, Actuality acts) or because it generates an infinite regress (Love loves love loves love…). In plain English: We need to think of God first and foremost as a noun, and not merely as a verb – in other words, as an Agent, rather than simply as an unlimited act of thought or love or “be-ing.”

Despite its flawed conception of God, Feser’s Thomistic proof is not without its merits: it highlights the sheer contingency of beings whose nature provides no guarantee of their existence, and it shows that any being whose existence is not explained by its nature cannot be regarded as a self-explanatory being. In so doing, it sets the stage for Feser’s fifth, Rationalist proof, which appeals to the Principle of Sufficient Reason in order to argue that beings which are not self-explanatory require an external cause for their existence, and that there must be an Ultimate Cause for the existence of these contingent beings, which is self-explanatory. However, the Rationalist argument for a necessary, self-explanatory Being, taken by itself, is unable to establish whether this Being possesses intellect and will. In his book, Feser appeals to the notion of a purely actual Being in order to demonstrate that this necessary Being must be intelligent, but I’ve already explained in my previous post why this approach fails. In the end, only Feser’s third, Augustinian proof, which argues for the existence of an Ultimate Mind, has any hope of taking us to a personal Deity. Accordingly, in my next post, I plan to discuss whether Feser’s fifth and third proofs, taken together, can establish the existence of an Ultimate Mind, which explains both its own existence and that of everything else.

==================================================================

===================================================================

A. FESER’S FOURTH, THOMISTIC PROOF

1. The four tiers of Feser’s Thomistic proof

Feser’s Thomistic proof is like a four-tiered wedding cake. Image courtesy of Fandom and Wikia.org.

Feser’s Thomistic proof may be likened to a four-layered wedding cake. At the foundation is the “first layer” of the argument, where Feser sets the scene by arguing for a real distinction between a thing’s essence and a thing’s existence, for the everyday things which we can experience. This corresponds to steps 1 to 11 of his Thomistic argument (2017, pp. 128-131).

The second layer is the one in which Feser attempts to establish that there must be some Ultimate Cause (or causes) in which essence and existence coincide, and which imparts existence to ordinary beings like ourselves, whose essence and existence are distinct. Feser’s arguments in support of this conclusion can be found in steps 12 to 23 of his proof.

The third layer of Feser’s proof is where he argues that this Ultimate Cause, whose essence is Pure Existence, must be a unique and necessary Being, Who sustains everything else in existence. This corresponds to steps 24 to 28 of the proof.

The fourth layer, or top tier, of the Thomistic proof (steps 29 to 36) is where Feser argues that the One Necessary Being must be a Purely Actual Being, which, he claims (citing arguments he has already put forward in his Aristotelian argument in chapter one) entails that this Being “must be immutable, eternal, immaterial, incorporeal, perfect, omnipotent, fully good, intelligent, and omniscient” (step 33). Such a Being, Feser concludes, can only be called God.

That’s Feser’s Thomistic proof in a nutshell. I’m going to begin my critique of Feser’s argument at the foundation, or bottom layer, where Feser endeavors to show that for the ordinary things we experience in the world around us, there is a real distinction between their essence and their act of existence.

2. Feser’s arguments for a real distinction between essence and existence, in empirical objects

(a) A preliminary disclaimer

Drawing of a unicorn by Friedrich Johann Justin Bertuch (1747-1822). We can describe the essence of a unicorn, but it does not exist. Thomists would say that a unicorn’s essence is not endowed with existence. Public domain image.

Before I begin my discussion of Feser’s fourth, Thomistic proof of God’s existence, I’d like to begin with a modest disclaimer: I will not be proposing or defending any philosophical theory of what it means for something to exist. That’s because I’m not totally satisfied with any of the existing theories. What I can tell you, from my studies of philosophy, is that no account of “existence” is without its problems. I should also state up-front that although I disagree with Dr. Feser’s account of essence and existence and find fault with the arguments he puts forward for it, it is nevertheless possible that it might turn out to be correct, at least for contingent beings. (On the other hand, I would maintain that Feser’s account of God as Existence Itself isn’t just contentious, but downright nonsensical.)

To illustrate the uncertainty that reigns in the field of philosophy on the question of what “existence” is, I’d like to quote from the first and final paragraphs of the article by Associate Professor Michael Nelson (University of California, Riverside) on Existence, in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Existence raises deep and important problems in metaphysics, philosophy of language, and philosophical logic. Many of the issues can be organized around the following two questions: Is existence a property of individuals? and Assuming that existence is a property of individuals, are there individuals that lack it?

I began by saying that existence raises a number of deep and important problems in metaphysics, philosophy of language, and philosophical logic. I have examined some of those problems and surveyed a number of different accounts of existence. None of the theories surveyed is wholly satisfying and without cost. The first view proposed by Frege and Russell treats existence as a second-order property and assimilates seemingly singular existentials to general existentials. The proposal requires descriptivism, the thesis that ordinary proper names have descriptive equivalences, which many find to be a problematic thesis. The second Meinongian view requires countenancing individuals that do not exist. We have seen the view face challenges in giving coherent and yet informative and compelling individuation principles for nonexistent individuals and all versions of the view suffer from the problem of metaphysical overpopulation. Finally I presented the naive view that existence is a universal property of individuals. That view faced the problem of having to reject the truth of highly intuitively true singular negative existential sentences like ‘Ronald McDonald does not exist’. The view also faces difficulties in properly accounting for the interaction of quantifiers and modal and tense operators. Existence remains, then, itself a serious problem in philosophy of language, metaphysics, and logic and one connected to some of the deepest and most important problems in those areas.

Bearing in mind that the topic of “existence” is a philosophical minefield, let us proceed to carefully examine Feser’s (and Aquinas’) theory of existence.

===================================================================

(b) Why does the distinction between “essence” and “existence” matter, and how does it relate to God?

Evolution of Sprite bottles over time. In an analogy below, I liken ordinary things’ essences to bottles of various kinds, and their existence to the Sprite beverage which is poured into them. This is roughly how Thomists view ordinary things. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

For the benefit of readers who don’t have a background in philosophy, I’d like to propose a simple analogy which I hope will help explain Aquinas’ (and Feser’s) views on essence and existence, and how they point to the existence of God. In a nutshell, Aquinas views the essences of ordinary things (including human beings) as mere vessels or receptacles for their existence, which is poured into them from outside. Things’ essences, considered purely in themselves, are not real: rather, they have the potential to be “real-ized,” just as an empty beverage bottle has the potential to be filled with Sprite. Different kinds of bottles may have different shapes, just as different kinds of things have different forms. Additionally, two bottles of the same shape are composed of different material, just as two things of the same kind contain different matter. Existence is something which things are endowed with, just as Sprite is something which bottles are filled with. But just as empty bottles, considered in themselves, are unable to tell us anything about the mysterious beverage known as Sprite, so too, essences which have a potential to be “real-ized” are incapable of explaining their own reality. And just as the beverage we call Sprite needs no bottle to contain it, so too, Pure and Unlimited Existence needs no separate essence to constrain it: its essence is simply to exist, and nothing more. It is Being Itself. Drawing on Aquinas’s writings, Feser goes on to argue that Pure Existence is unique, that it exists necessarily, and that it’s fully actual, which (he argues) means it’s perfect, omnipotent and omniscient, and deserves to be called God.

No analogy is perfect, however. In order to avoid misunderstandings, I’d like to point out two flaws in the analogy I have proposed. One flaw in the foregoing illustration is that bottles may be filled with different kinds of beverages: for example, Coca Cola, Fanta and orange juice, in addition to Sprite. Existence, however, doesn’t come in different flavors: the only thing, according to Thomists, which differentiates my existence from yours is that my individual essence (as this human being) is distinct from your essence, as that human being. More precisely: even though you and I are two individuals of the same kind (i.e. human beings), my signate matter is distinct from yours, as my flesh and bone is not the same as your flesh and bone. However, Aquinas contends that something which is Pure Existence would contain all perfections, making it rather like an imaginary beverage which somehow contains all flavors within itself.

Another limitation of the foregoing illustration is that the Sprite in a bottle is completely separable from the bottle containing it (e.g. when the bottle is emptied), whereas Feser holds that the essence and existence of an ordinary thing are really distinct but inseparable from one another. How two terms can be really distinct but nonetheless inseparable is a subject we’ll explore below.

===================================================================

(c) What does Feser mean by “essence” and “existence”?

|

|

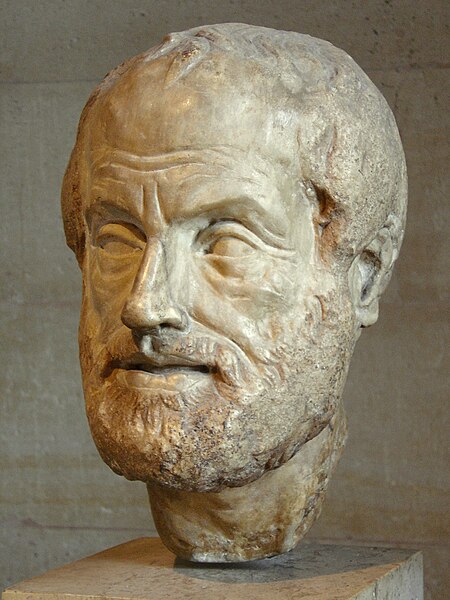

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (left) defined the essence or nature of a human being: man, he said, is a rational animal. Centuries later, the Aristotelian philosopher, St. Thomas Aquinas (right) drew a distinction between a man’s essence and his existence

Left: Portrait bust of Aristotle; an Imperial Roman (1st or 2nd century AD) copy of a lost bronze sculpture made by Lysippos. Image courtesy of the Louvre Museum, Eric Gaba and Wikipedia.

Right: image of St. Thomas Aquinas in stained glass, courtesy of Beao and Wikipedia.

———————————

But what exactly is a thing’s essence, anyway? And what do Thomists mean by “existence”? As we’ll see, Feser expresses himself in several contradictory ways, when explaining what a thing’s existence is.

A thing’s essence is defined by Feser as “what it is” (2017, p. 117), or “its very nature” (2017, p. 119), whereas a thing’s existence is defined as “the fact that it is” (2017, pp. 13, 117).

Are essences real?

Let’s begin with essences. The most radical critique that could possibly be directed at Feser’s argument for a real distinction between a thing’s essence and its existence is to deny outright that things have any essences in the first place.

There are philosophers who reject essentialism, or the view that there are essences in the natural world. Nevertheless, it remains a philosophically respectable position, as readers can verify for themselves by perusing Alexander Bird’s article on Natural Kinds in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. A strong case can be made for the assertion that statements like ‘Water is H2O’ and ‘Gold is the element with atomic number 79’ are necessary truths, which specify the essence of some natural kind.

The term “natural kind” has various definitions in the philosophical literature. However, it is generally agreed that (i) the members of a natural kind should have some natural properties in common (e.g. the class of “white objects,” to use one of J.S. Mill’s examples, does not comprise a natural kind, but the class of atoms having an atomic number of 79 does – viz. gold); (ii) natural kinds should permit inductive inferences to be drawn by scientists; (iii) natural kinds can be described by laws of nature; (iv) the members of a natural kind should form a “kind” of some sort; (v) natural kinds should form a hierarchy (e.g. in the field of biology, Linnaeus’s taxonomy provides an especially clear example of such a hierarchy, while in the standard model of quantum physics, the various kinds of fundamental particles (electron, tau neutrino, charm quark) fall into broader categories (lepton, quark), which fall themselves under higher kinds (fermion, boson)); and (vi) natural kinds should be categorically distinct – in other words, there cannot be a smooth transition from one kind to another. Chemistry provides the best example of requirement (vi), insofar as there are no intermediates between neighboring atoms in the periodic table, such as chlorine (element no. 17) and argon (no. 18). The claim that natural kinds have essences is a stronger philosophical claim, but in recent years, an increasingly large number of philosophers have articulately defended this view – notably, Saul Kripke, Hilary Putnam, Brian Ellis (whom Feser quotes in his book), E. J. Lowe, Nancy Cartwright and David Oderberg, author of Real Essentialism (Routledge, 2008), who is also quoted by Feser.

In Aristotle’s day, the world of living things afforded the most obvious evidence for the claim that there are natural kinds, with essential properties. But ever since Darwin demonstrated that species change over the course of time, biological essentialism has become philosophically contentious, and as Bird notes in his article, chemical kinds have now replaced biological kinds as the paradigms of natural kinds. Even so, species essentialism continues to have some notable exponents, and the article on Species in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy even has a special section on what it calls The New Biological Essentialism.

In any case, Feser is not committed to species essentialism: indeed, he even declares (2017, p. 145) that he could happily concede that there are no biological essences, if pressed, while still maintaining that the physical particles which make up material objects have clear-cut essences.

Finally, as Feser points out, citing an argument defended by the philosopher Crawford Elder, the view that all essences are constructs of the human mind is self-refuting, as it would entail that the essence which we call “mind” – whether we think of it as the brain or as something immaterial is irrelevant here – is itself a construct of the mind, which means that the mind is both prior to and posterior to itself. (Of course, this argument assumes that the word “mind” denotes an essence, which a skeptic might question. However, it should be clear from the foregoing remarks that essentialism is alive and well, in philosophical circles.)

What does Feser mean by a thing’s existence?

Feser highlights the distinction between the an object’s essence and its existence by pointing out (in a passage which I’ll discuss below) that “you can know a thing’s essence without knowing whether or not it exists” (2017, p. 118). The phrase “whether or not it exists” would appear to suggest that a thing’s existence is a Boolean data type, with only two possible values: true or false. Alternatively, the phrase, “the fact that it is,” might suggest that a thing’s existence is simply the proposition that it exists. Indeed, Feser’s discussion of human beings in an example he provides on page 117 of his book lends support to this interpretation: he points out that you can know “the nature or essence of a human being” without knowing “that there really are human beings,” which seems to imply that a human being’s existence (as opposed to its essence” is simply the proposition that human beings exist.

But this clearly will not do. For Feser wants to argue that there is one Being – God – in Whom essence and existence are identical. And it is absolutely impossible for a being’s essence to be identical with either a Boolean (true-false) data type or a proposition, no matter what kind of being it is. To equate a being’s essence with a data type or a proposition would be to commit a category mistake, like saying that a joke has wheels or that happiness is four-legged. If having an essence identical with its existence were a defining feature of anything worthy to be called “God,” then Feser’s argument would be tantamount to a proof of atheism – something I am sure he does not intend it to be.

Is there a better way of understanding what Feser means by “existence”? Fortunately, there is: we can consider it as a first-order predicate of individual objects – an interpretation which Feser himself endorses, later on in his book (2017, pp. 135-138). In order to support this interpretation, I’d like to begin by quoting a short passage from Dr. Nelson’s article in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (which I cited above), where he succinctly contrasts Aristotle’s and Aquinas’ views on the question of existence:

Aristotle seems to have seen nothing more to existence than essence; there is not a space between an articulation of what a thing is and that thing’s existing. Saint Thomas Aquinas, on the other hand, famously distinguished a thing’s essence from its existence. Aquinas argued something as follows, in chapter 4 of his On Being and Essence. One can have an understanding of what a man or a phoenix is without knowing whether it exists. So, existence is something in addition to essence. In short, Aquinas argued that existence is a separate property as existence is not part of most objects’s natures and so those objects can be conceived or thought of separately from their existing.

This is roughly correct, but not quite. As Dr. Feser points out in chapter four of his book, Aquinas regarded existence as “a first-order predicate of individual objects” (2017, p. 135), but not as a property of objects:

That we can predicate existence of a thing doesn’t entail that it is a property or other accident, however. It is, from the Thomist’s point of view, not a property or accident, for a thing can have properties or other accidents only if it first exists. (2017, p. 138)

So now we know what Feser means by a thing’s essence and what he means by its existence. Feser, like other Thomists, maintains that there is a real distinction between an entity’s essence and its existence. What does he mean by that?

===================================================================

(d) What does Feser mean by a real distinction?

The radius and circumference of a circle are really distinct from one another, despite the fact that each is inseparable from the other. Image courtesy of Optimager and Wikipedia.

In his latest book, Five proofs of the Existence of God (Ignatius Press, 2017), Feser makes it clear that a real distinction is not to be confused with a merely conceptual distinction, but he defines these terms only in passing. A more rigorous treatment of the subject can be found in Feser’s earlier work, Scholastic Metaphysics (editiones scholasticae, 2014, pp. 72-73), where he states that for Thomists, a real distinction “reflects a difference in extra-mental reality,” which “holds entirely apart from the way the intellect conceives of a thing,” whereas a logical distinction is one which “reflects only a difference in [our] ways of thinking about this extra-mental reality.” For example, “individual objects like people, dogs, trees and stones are really distinct,” and the various parts of an individual object are also really distinct. Additionally, there is a real distinction between a thing (e.g. a stone) and its positive accidents (e.g. its color), and there is also a real distinction between the various accidents of a thing (e.g. between a stone’s color and its shape). We can even speak of a real distinction between a thing and its modes – say, between a stone on the one hand and its current location, state of rest or state of motion on the other – even though the latter has no being apart from the former. (Feser’s thinking on this subject follows that of Aristotle, who placed a thing in the category of substance, and its location in the category of place – see here for Professor Taylor Marshall’s excellent summary of Aristotle’s ten categories. Writing 2,000 years before the advent of Newtonian physics, Aristotle had no category for a thing’s state of motion, but it strikes me as entirely reasonable, and broadly in keeping with Aristotle’s ontology, to create an eleventh category, in order to accommodate this concept.)

As an example of a conceptual or logical distinction, Feser provides several illustrations: the purely verbal distinction between a bachelor and an unmarried man (2017, p. 117), or between “human being” and “rational animal” (2014, p. 73), or the somewhat stronger, virtual distinction between a man’s rationality and his animality (2014, p. 74), which coincide in human beings, but which can nevertheless be mentally considered in isolation from one another, even in creatures like ourselves. I find the last example puzzling, however, as Feser elsewhere declares: “The essence of human beings, rational animality, has rationality and animality as parts” (2014, p. 246). I would have thought it obvious if A and B are parts of C, then the distinction between A and B is a real one. But let that pass.

In both his earlier work, Scholastic Metaphysics (editiones scholasticae, 2014) and his recent book, Five proofs of the Existence of God (Ignatius Press, 2017), Feser insists that a real distinction between A and B does not imply their separability, and he cites an example provided by the metaphysician, David Oderberg: the radius and circumference of a circle are obviously really distinct from one another, since the latter is two pi times the former; nevertheless, they are inseparable, for it is impossible for a circle to have a radius without having a circumference, or vice versa.

Now that we understand what Feser means by essence, existence and a real distinction, we are finally in a position to critically evaluate his arguments that there is indeed a real distinction between a contingent being’s essence and its existence.

===================================================================

(e) Feser’s three arguments for a real distinction between essence and existence

Very briefly, Feser’s three arguments for a real distinction between an ordinary thing’s essence and its existence can be summarized as follows. First, I can know what something is, without knowing whether anything of that kind actually exists. For instance, the Thylacine (also known as the Tasmanian tiger or marsupial wolf) is an animal whose natural characteristics have been extensively studied and described by scientists, but whose existence remains the subject of lively dispute: despite the fact that it is supposed to have died out in 1936, there are many people who claim to have seen it in recent years. Second, the contingency of material things, or the fact that they can come to be and pass away, indicates that their existence does not belong to them by nature. The dodo, for instance, died out 350 years ago. Third, if there were something whose essence and existence were identical, then that thing would have to be something whose essence just is existence itself. Obviously, there cannot be two such things; hence, if the essence and existence of ordinary things is identical, then we are forced to accept the radical thesis that there is only one thing in the entire cosmos (Monism), which Feser takes to be a philosophically absurd position. I will discuss these and other arguments put forward by Feser for a real distinction between essence and existence, below.

===================================================================

(i) Feser’s first argument: I can know what something is, without knowing whether it actually exists

A life restoration of the largest known specimen of a pterodactyl. Feser contends that because I can know what a pterodactyl is without knowing whether such creatures still exist, a thing’s “whatness” or essence must be really distinct from its existence. Image courtesy of Matthew Martyniuk and Wikipedia.

Feser’s first argument for a real distinction between essence and existence is that I can know what a thing is, without knowing whether it is:

Consider first that you can know a thing’s essence without knowing whether or not it exists. Suppose a person had, for whatever reason, never heard of lions, pterodactyls, or unicorns. Suppose you gave him a detailed description of the natures of each. You then tell him that of the three creatures, one exists, one used to exist but is now extinct, and the third never existed, and you ask him to tell you which is which given what he now knows about their essences, he would of course be unable to do so. But then the existence of the creatures that do exist must be really distinct from their essences, otherwise one could know of their existence merely from knowing their essences… [I]f the essence and existence of a thing were not distinct features of reality, knowing the former should suffice for knowing the latter, yet it doesn’t. (2017, p. 118)

Does Feser’s argument work at the individual level?

While Feser’s argument initially appears quite plausible when we consider the essence of a thing (say, a pterodactyl) at the generic or specific levels, it fails altogether at the individual level. I cannot know what a particular thing is, without at the same time knowing that it is. This is important, because as we have seen, Feser regards existence as a first-order predicate of individual objects. That being the case, it is very odd that we are unable to distinguish our knowledge of an individual thing’s essence (or what-ness) from our knowledge of its existence (or that-ness).

Now, I imagine that Feser may attempt to respond at this point with a counter-example. In his book, The Last Superstition (St. Augustine’s Press, 2008) he illustrates his claim that there’s nothing about an essence which guarantees its existence, with the aid of an example involving three individuals, one dead, one living and one fictional: Socrates, George Bush and the Batman character Bruce Wayne (2008, pp. 103-104). But in the case of the fictional character Bruce Wayne, we know who he is, either (a) by way of a general description – e.g. a wealthy American playboy, philanthropist, and owner of Wayne Enterprises, who, after witnessing the murder of his parents as a child, swore vengeance against criminals – which still does not get to the heart of the individual’s true “whatness,” as it only holds true of that individual contingently, or (b) by way of reference to other fictional particulars – e.g. the son of Dr. Thomas Wayne and Martha Wayne – whose identity remains undefined. So I think Feser’s fictional example is an unconvincing one. There is no true sense in which I can know an individual’s “whatness” without knowing that he exists. There are of course individuals whose historicity remains disputed: Biblical scholars disagree as to whether Moses was a real person, for instance. But even here, it should be apparent that we remain unacquainted with these individuals’ true “whatness,” and are forced to substitute a general description in its place – which is the very reason why these individuals’ existence remains a contentious issue.

Two types of knowledge: why Feser’s argument fails at the specific level

Even if at the specific level, however, what Feser’s argument for a real distinction between essence and existence overlooks is that there is a profound difference between knowing what something is, and knowing that [or whether] some proposition is true. The former kind of knowledge relates to the meaning of a term (e.g. “pterodactyl”), whereas the latter kind of knowledge relates to the truth of a statement about that term (e.g. “Pterodactyls exist.”) The fact that I can know what a pterodactyl is, without knowing whether it is, does not entail that there is some difference between its “whatness” and its existence; rather, all it implies is that “knowing what” and “knowing whether” are different, and that a term is not the same as a statement, or proposition containing that term.

In short: what Feser’s argument points to is a distinction between two types of knowledge – knowing what and knowing that – rather than a distinction between two metaphysical parts of an ordinary thing.

How Feser should argue for a real distinction between essence and existence, and why it won’t work

Supposing (hypothetically) there were indeed a real distinction between a thing’s essence and its existence, what would a good argument for such a distinction look like? Let’s consider Feser’s case of pterodactyls. An argument which established that I could know what a pterodactyl is, without knowing what a pterodactyl’s existence is, would indeed point to a real distinction between a pterodactyl’s essence and its existence. But in fact there is no such argument: to know what a pterodactyl is is simply to know its unique form of existence, with all its possibilities and constraints. And even if pterodactyls had never existed, we would still grasp what it would mean for them to exist, simply by grasping their natures.

What Feser’s argument actually establishes: a real distinction between matter and form, rather than between essence and existence

At this point, an Aristotelian critic might object: even if we needed to invoke a real distinction in order to explain the fact that I can know what a pterodactyl is, without knowing whether it still exists, the distinction in question would not be an essence-existence distinction, but a form-matter distinction. On the Aristotelian-Thomistic view of the intellect, whenever I grasp the concept of a pterodactyl, my intellect receives its substantial form, abstracted from the signate matter of any particular entity which happens to instantiate the form in question. Because my intellect receives a form abstracted from matter, it cannot know, simply by understanding what this form is, whether or not anything exists in Nature which possesses this form. That alone is enough to explain how I can know what a thing is, without knowing whether it exists. There is no need to postulate an additional distinction between a thing’s essence and its act of existence.

(Note: An argument along these lines was first put forward by the philosopher David Twetten, in his 2006 paper, Really Distinguishing Essence from esse, in Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics 6:57-94. Twetten considers this argument to be a strong one, but he also thinks a Thomist can answer it, as we’ll see below.)

An objection from Feser: form and matter cannot explain the actual existence of an object

In his work, Scholastic Metaphysics (editiones scholasticae, 2014) Feser argues that the form-matter distinction is incapable of accounting for the actual existence of ordinary things. Summarizing an argument first developed by David Twetten in 2006 and formulated independently by Feser in a 2011 paper, Feser responds to the Aristotelian objection above, as follows:

To avoid acknowledging that there is a real distinction between a thing’s essence and existence, the imagined Aristotelian critic will have to be able to account for a material thing’s being actual in terms of its essence – that is, its matter and form – alone. But its matter alone cannot be what accounts for it, since matter by itself is pure potency and thus cannot account for actuality. Nor can its form alone be what accounts for it, since on an Aristotelian view form is not actual in the first place apart from matter. Furthermore, form alone cannot account even for a material thing’s continued actuality once it comes into being, for if it could do so, it would continue in being after the substance of which it is the form was destroyed (which on an Aristotelian view it does not). Nor can the substance comprising form and matter together account for its own actuality, since this really amounts to the form, qua what actualizes the matter so as to make a substance, being the explanation of the actuality of the whole – which, for the reasons just given, cannot be the case. So, there must be something really distinct from a thing’s form and matter, and thus really distinct from its essence, that accounts for its actuality. (2014, p. 249)

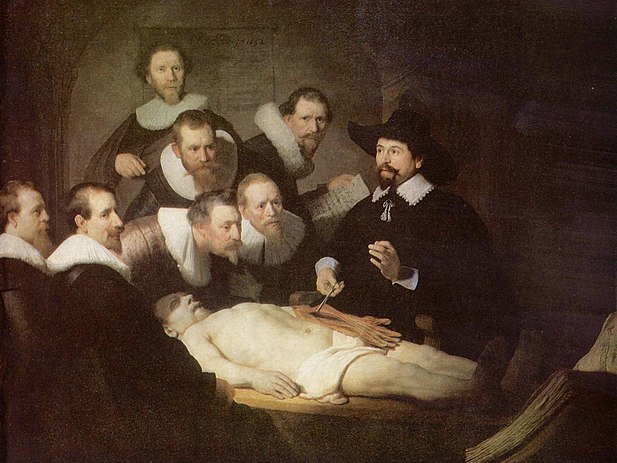

“The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp” by Rembrandt van Rijn (1632). Mauritshuis, Amsterdam. Image courtesy of The Yorck Project and Wikipedia. According to Thomists, living things have a single substantial form, which grounds all of their natural properties. This form departs when a living thing dies. The only thing a corpse has in common with the living thing it once was is prime matter, or pure passive potency, as Thomists describe it. Such a view fails to explain why a corpse has the same shape, size and weight as the living body it once was, despite not having any form in common with the living body. Other Scholastic philosophers argued that the form of a living thing is superimposed on top of the underlying form of a corporeal thing, and that the latter form remains after death, accounting for the physical similarities between a living thing and its corpse.

Now, I could contest certain points in the foregoing argument – for instance, Feser’s assertion that “matter by itself is pure potency.” A Thomist would agree with that, but it is doubtful whether Aristotle would have done so. Even among Scholastic philosophers, the claim that prime matter is utterly devoid of any actuality is a contentious one: Scotists and Suarezians deny it, and Thomists, who uphold it, are forced to accept the absurd view that when an animal dies, its corpse has absolutely nothing in common with the animal it once was, except for pure passive potency – which fails to explain why the corpse has the same shape, size and weight as the original animal.

Nor can I see why the claim that form and matter together account for a thing’s actuality should entail that form alone can account for a thing’s actuality. Feser thinks this follows because form actualizes matter. I would contend that Feser has been misled by his own woolly terminology: the term “account for” is a vague one. If we simply say that anything which is a composite of form and matter actually exists, then we are saying something which is trivially true, on an Aristotelian account. Such a claim in no way entails the outlandish claim that anything which is a form without matter actually exists.

However, it appears to me that Feser’s argument is marred by a more fundamental flaw. Feser seems to be arguing as follows:

1. If there is no real distinction between a material thing’s essence (i.e. its form plus its matter) and its existence, then a thing’s essence must be able to account for its existence.

2. However, a material thing’s essence is unable to account for its existence – regardless of whether we consider form alone, matter alone, or the composite of form and matter.

3. Therefore, there is a real distinction between a material thing’s essence and its existence.

The argument is valid, but I would reject the first premise as false. What we should say instead is:

1(b): if there is no real distinction between a material thing’s essence and its existence, then whatever accounts for a material thing’s existence also accounts for its essence, and vice versa.

I see no reason why an Aristotelian would have any problem accepting premise 1(b), since it applies to individual essences, which are composed of form and signate matter – for instance, an actual lion consists of the universal form of a lion, realized in this flesh and these bones. And there is nothing problematic in someone’s holding that whatever accounts for the existence of this lion also accounts for its essence, as an individual of that species. [By contrast, the universal essence of a lion consists of “matter in general,” or common matter, plus its universal form.]

Immaterial intelligences: a problem for the traditional Aristotelian view?

Dante and Beatrice gaze upon the highest Heaven, the Empyrean. From Gustave Doré’s illustrations to the Divine Comedy, Paradiso Canto 28, lines 16–39. Public domain image from Alighieri, Dante; Cary, Henry Francis (ed) (1892) “Canto XXXI” in The Divine Comedy by Dante, Illustrated, Complete, London, Paris & Melbourne. Courtesy of Wikipedia. Feser argues in his Scholastic Metaphysics that immaterial intelligences, such as angels, constitute a difficulty for the traditional Aristotelian view that a thing’s essence is identical to its existence. Aristotle didn’t believe in angels, of course, but he did believe that immaterial beings moved the heavenly spheres.

Feser briefly raises another argument against his imagined Aristotelian critic, in his Scholastic Metaphysics (editiones scholasticae, 2014): namely, that the form-matter distinction fails to explain how immaterial intelligences, which are composed of form alone, could possibly exist (2014, p. 248). Aristotle himself believed in the reality of such intelligences. However, there is a very good reason why Feser does not mention this argument in his more recent work, Five Proofs of the Existence of God (Ignatius Press, 2017): namely, that to do so would be question-begging. For what Feser is attempting to establish, in his Thomistic proof of the existence of God, is that “the essences of things of our experience must be distinct from the existence of those things” (2017, p. 119). Since we are material beings, we can have no experience of immaterial intelligences.

The incompleteness of our ideas of non-existent objects

A phoenix depicted in a book of legendary creatures by FJ Bertuch (1747–1822). Below, I argue that there is no essence of a phoenix: our concept of a phoenix is only skin-deep. Public domain image from Friedrich Justin Bertuch, Bilderbuch für Kinder (Eigenbesitz), Fabelwesen (1806). Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Another objection to the traditional Aristotelian view raised by Feser is that it fails to account for the essences of imaginary creatures, such as phoenixes and unicorns. As Feser puts it:

Unicorns, if they existed, would be composites of form and matter. Yet they don’t exist. Thus the existence of things that do exist must be something added to their form and matter. (2014, p. 248)

However, it is doubtful whether we actually have any proper concepts of non-existent kinds of objects. (When I say “kinds,” I mean natural kinds; arithmetical and geometrical objects, such as numbers and shapes, are of no concern to me here.) At first blush, the question might appear ridiculous: after all, don’t we all have a clear and distinct idea what a unicorn is? Actually, we don’t. A clear image is not the same thing as a clear idea, or concept, as any good Aristotelian could tell you. Our concept of a unicorn, like that of a winged horse or for that matter, a phoenix, is only skin-deep: we have no idea of how these creatures are supposed to develop, or of their internal anatomy (for example, what is a unicorn’s horn made of, and does it grow back if you cut it off?) Our only complete ideas, it seems, are of actually existent objects – or at the very least, objects which have actually existed at some time (such as mammoths).

Even with long-extinct creatures (such as dinosaurs), our concepts of these creatures are fragmented and incomplete, owing to the fact that we only have their bones (and recently, impressions of their skin as well), but not their skin collagen, let alone their DNA.

What I am proposing, in short, is that the only way to have a complete concept of any kind of entity is by making or discovering one, and that the ideas we have of imaginary creatures (such as unicorns and phoenixes) are actually parasitic on our fully fleshed-out concepts of actually existent creatures. A thing has to actually exist, at some time, in order for it to have a true essence.

===================================================================

(ii) Feser’s second argument: the contingency of things indicates that their existence does not belong to them by nature

Lion at a South African waterhole. The existence of lions is a contingent fact, as Feser correctly points out. Image courtesy of Bernard Dupont and Wikipedia.

Feser’s second argument for a real distinction between a material thing’s essence and its existence is that material things are contingent, whereas if their existence were identical to their nature, then they would exist by virtue of their nature, which is manifestly false:

A second reason why the essences of the things of our experience must be distinct from the existence of those things has to do with their contingency – the fact that, though they do exist, they could have failed to exist. For example, lions exist, but had the history of life gone differently, they would not have existed; and it is possible that lions could someday go extinct. Now, if the existence of a contingent thing was not really distinct from its essence, then it would have existence just by virtue of its essence. (2017, p. 119)

The last sentence, as it stands, makes no logical sense: if a contingent thing’s essence is identical to its existence, then all that follows is that for a contingent thing to have an essence is identical to that thing’s having existence. However, it does not follow that the thing in question is necessary (contrary to our initial stipulation that it is contingent); that conclusion would only follow if a thing’s essence were in some way necessary. Feser has given us no reason to think that a thing’s essence is necessary, in his Thomistic argument for the existence of God.

The force of Feser’s second argument can be blunted by freely granting that the existence of contingent things requires a cause (or causes) of some sort. But by the same token, that cause could equally be said to generate things’ natures. Feser writes as if the natures were already there, in some shadowy “potential” realm, just waiting to have the fire of existence “breathed into” them – a supposition which begs the question by assuming at the outset that the two are distinct.

Henry of Ghent’s view: things’ essences require an explanation, too

The medieval philosopher Henry of Ghent (1217-1293) argued that a contingent being’s act of existence (in Latin, esse) is not something added to its nature; rather, the thing itself, in its very essence, can only be explained by its ultimate cause, which keeps it in being. For Henry, this Ultimate Cause was of course God. David Twetten (2006) summarizes this view as follows:

For Henry, no creature has esse [the act of being – VJT] considered absolutely in itself, but only insofar as it is considered in relation to its ultimate cause — as an effect and as a likeness of the divine esse. Therefore, ‘to be’ is not something added as though to something else that already is, but is simply the creature itself insofar as it is related as an effect to the divine essence in the order of efficient causality, just as essence is the creature itself as related by way of likeness to the divine essence in the order of formal causality. To exist, Henry would say, is simply for a thing to be posited outside its causes. (2006, p. 91)

However, Twetten rejects this proposal, on the grounds that it makes a thing’s very identity relative to that of its cause. Following the Scholastic philosopher Suárez, he thinks that this would relativize God’s existence, too:

No less than the greatest critic of the Real Distinction [between essence and existence – VJT], Francisco Suárez, has shown the inadequacy of this alternative, however. To say of a thing ‘it is’ predicates not something relative but something ‘absolute’ of the thing, observes Suárez. Otherwise, to say that God is would also be to introduce a relation to a cause. It remains that if we must account for ‘actually to be’ by something other than form, ‘actually to be’ must be a really distinct component intrinsic to things that are. (2006, p. 91)

I have to say that Suárez’s argument strikes me as a total non sequitur. If there is an Uncaused Being, then by definition, its essence cannot be defined in relation to any cause. There is no contradiction in defining the essence (or identity) of a material thing in relation to that of its cause, while maintaining that an Uncaused Cause (whatever it may be) possesses an essence in an absolute, non-relative manner. For theists, of course, this Uncaused Cause will be God Himself; for atheists and pantheists, it will presumably be some ultimate level of physical reality. Thus of God, theists can not only say, “In Him we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28), but also, “In Him we live and move and have our identity.” Thomists seem to be insisting that the identity (or essence) of things can be defined independently of their relation to their Ultimate Cause – which strikes me as a very odd position for a theist to take.

Where do essences come from?

What I am suggesting, in other words, is that Thomists don’t take the Christian doctrine of creation ex nihilo seriously enough. Instead of saying that God made all creatures out of absolutely nothing, they seem to reduce God’s creative activity to endowing some shadowy essences with existence, thereby making them real. But that only begs the question: where did the essences come from?

St. Augustine’s famous answer to this question was that universals (including the idea of a lion) exist in the Mind of God – a solution which Feser discusses in chapter three of his book, and which will be the subject of my next post, in which I’ll evaluate his proof of God’s existence. (It is interesting to note, in passing, that St. Augustine himself saw no need to posit an essence-existence distinction, in order to explain why some of God’s ideas have actually existent counterparts, while others do not.) But even this picture does not go far enough: it suggests an image of God as an artist, playing around with different concepts of beings that He could create, and then picking a subset, and saying: “Right. I’ll create these ones; the rest I don’t need in the world I’ve chosen to make.” Rather, what a theistic philosopher should say is that God decides to “flesh out” a concept, making it complete in every detail, only when He decides to create actually existent things which instantiate that concept. Or putting it in modern terminology: essence does not precede existence, even logically; rather, the two go hand-in-hand.

To be fair, I would like to acknowledge that Feser’s second argument for a real distinction between essence and existence contains a significant metaphysical insight: namely, that contingent things’ natures do not explain their existence, and that some external cause is needed to do so – a point I’ll address at further length in my next post, when I examine Feser’s fifth, Rationalist Proof of God’s existence. Even so, it does not follow that contingent beings’ natures and existences are distinct from one another. “A cannot explain B” does not entail that A is really distinct from B; all it shows is that if they are the same, then B cannot be self-explanatory. God is the Author of the nature and existence of contingent things: the two are not really distinct, after all.

===================================================================

(iii) Feser’s third argument: anything whose essence is its existence would have to be Pure Existence itself

Feser’s background metaphysical assumptions – and where they spring from

In order to appreciate Feser’s third argument for a real distinction between a thing’s essence and its existence, we need to grasp certain metaphysical assumptions Feser makes about existence, which he never takes the trouble to spell out in his book. Indeed, I had to go back to his earlier work, Aquinas (Oneworld Publications, Oxford, 2009), to find a clear statement of them.

The first of these assumptions is that existence, considered in itself, is something simple; and the second is that existence, considered in itself, is unlimited. On this picture, what limits and fragments existence are the various receptacles into which it is poured: the essences of things. Without any such receptacle, a thing’s existence would be utterly unbounded, and free from all limitations.

The reason why Feser endorses these metaphysical assumptions is that he views existence as a perfection, as he acknowledges in a passage on Aquinas’ famous Fourth Way of proving God’s existence:

In particular, he [Aquinas] holds that in general (and not just with respect to being or existence) things that have some perfection only to various limited degrees must not have that perfection as part of their essence, “for if each one were of itself competent to have it, there would be no reason why one should have it more than another” (QDP 3.5). That is to say, if it were part of a thing’s very essence to have the perfection, then there would be no reason not to possess it in an unlimited way. (Hence any human being is fully human, which follows from humanity being part of his or her essence, but does not have being to the fullest extent – which would be possible only for something whose essence just is being – or goodness to the fullest extent – which would be possible only for something in some sense having within it every perfection – and so forth.) So, for a limited thing to have some perfection, it must derive it from something outside it…

But if the ultimate cause is unlimited in goodness, truth, nobility, or whatever other transcendental we are starting with, then (as we have already said) given the convertibility of the transcendentals it will also have to be unlimited in being and therefore just be pure being or existence itself. (2009, p. 109)

According to Feser, Aquinas holds that for any perfection – and not just existence – if a thing possesses it as part of its essence, then it must possess to to an unlimited degree. Clearly, by implication, existence is a perfection, for Feser. Existence is distinguished from other perfections by being a transcendental, which Feser defines as “something above every genus, common to all beings and thus not restricted to any category or individual” (2009, p. 33).

A third generation Toyota Century at the 2017 Tokyo Motor Show. The Toyota Century is a luxury car, which is often used by the Imperial House of Japan, the Prime Minister of Japan, senior Japanese government leaders, and high-level executive businessmen. Thomists hold that “existence” is a perfection, in addition to all of the other features which make a luxury car great. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

What is odd about the foregoing passage is that it treats existence as a perfection which a being possesses, in addition to the other perfections it has, instead of simply viewing those perfections as various forms of existence. As a former philosophy lecturer of mine, Professor Bill Ginnane (1929-2007), used to point out, it would be very strange if someone were to list the perfections that a good car should possess – for example, a 5.0 litre V12 engine, double wishbone suspension, an infotainment display, a WiFi hotspot, heated seats and steering wheel, automatic headlamps, and remote keyless entry [I’ve updated his list of features from the 1980s, when I heard him lecture] – and then add existence as another perfection. And it would be even stranger if that person were to then declare that existence was the greatest perfection a car could possess, and that all of the other perfections were of infinitely less importance. To be sure, as Feser would point out, a car is not a natural object but an artifact, but ask yourself this: would it sound any less strange if we were to list the perfections which a good lion should possess, and then add existence as the greatest of them all?

It should be clear from the foregoing passage that Feser regards being or existence as an unlimited perfection; however, the reader may still be wondering why he regards it as a simple one. What is there to prevent a perfection from being complex? The answer is that a transcendental perfection such as being is devoid of all potentiality, considered in itself; whereas if it had parts, these parts would have the potential to come together or to separate.

Let us now return to Aquinas’ argument (quoted by Feser above) that things which possess some perfection only to a limited degree must not have that perfection as part of their essence, “for if each one were of itself competent to have it, there would be no reason why one should have it more than another” (QDP 3.5). The flaw in this argument, as I see it, is that it fails to distinguish between the concepts “unlimited” and “complete.” A thing which has some perfection essentially possesses it completely, but that does not mean that it possesses it to an unlimited degree.

Another distinction which Aquinas fails to draw is that between “indefinite” and “infinite” (or unlimited). In and of itself, the bare concept of “existence” is neither limited nor unlimited, but rather, indefinite. To say that a thing exists does not tell us anything at all about that thing.

The fact that the concept of existence is indefinite also explains why it is devoid of any potentiality. Aquinas attempts to infer from this fact that existence is something inherently simple; but what we should say is that existence, per se, is neither simple nor complex: it is inherently undetermined.

Feser’s anti-monistic argument for a real distinction between essence and existence

Image of a base jump from Earth, courtesy of Christophe Michot and Wikipedia. Feser’s third argument for a real distinction between essence and existence makes a huge and unwarranted logical leap from “There is a being whose essence is identical with its own act of existence” to “There is a being whose essence just is existence itself.” The latter does not follow from the former.

And now, at last, we are in a position to grasp Feser’s third and final argument for a real distinction between essence and existence, which is that identifying the two would entail the radical thesis that there is only one thing in the entire cosmos (Monism). Feser takes this conclusion to be a reductio ad absurdum, and I agree that if his argument worked, it would be.

In his informal statement of the argument, Feser reasons as follows:

A third reason why the essence and existence of each of the things we know through experience must be distinct is that if there is something whose essence and existence are not really distinct – and we will see presently that there is and indeed must be such a thing – then there cannot in principle be more than one such thing. For consider that, if some thing’s essence and existence are not really distinct, then they are identical; and if they are identical in that thing, then that thing would be something whose essence just is existence itself. (2017, p. 120)

As it stands, this argument contains a glaring non sequitur, which undermines the cogency of Feser’s case. It is by no means apparent why a being whose essence and existence are identical would have to be something “whose essence just is existence itself.” All that follows is that the essence of such a being would be identical with its own act of existence. As we shall see below, this non sequitur causes Feser’s entire proof to collapse, in its later stages.

We can make some sense of this apparent lapse of logic on Feser’s part by recalling his remarks above on perfections. As we saw, Feser holds that any being which possesses a perfection as part of its essence, possesses it fully. Thus any human being is fully human; and likewise, anything whose essence is being itself is fully a being, containing within its nature every perfection.

That is Feser’s underlying thinking, but it still doesn’t really answer our question, as it assumes (without justification) that “existence” is a single perfection. Then and only then would it follow that a being whose essence is identical to its existence is a being “whose essence just is existence itself.”

Why Feser maintains that there can only be one being which is existence itself

|

|

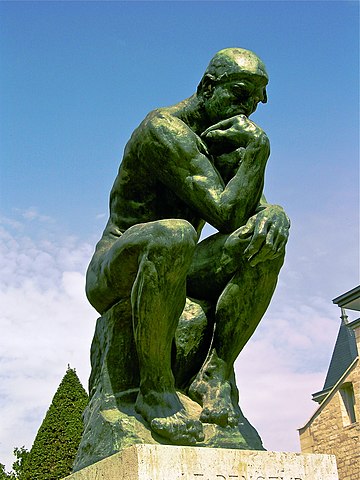

Above: images of two individuals of different species. Following Aquinas, Feser argues that if “existence” were a common genus to which they both belonged, then the specific difference between them would have to be something other than “existence” – which is impossible.

Left: A photo of The Thinker by Rodin located at the Musée Rodin in Paris. Courtesy of Andrew Horne and Wikipedia.

Right: Chimpanzee named “Gregoire,” born in 1944 and photographed in 2006 at the age of 62, at the Jane Goodall sanctuary of Tchimpounga in Congo Brazzaville. Courtesy of Delphine Bruyère and Wikipedia.

———————————

Next, Feser attempts to show that there cannot be more than one thing that just is existence itself. For if there were two such beings (let’s call them A and B), what could possibly differentiate them?

There are only two possibilities. A and B might be differentiated in the way two species of the same genus are differentiated; or they might be differentiated in the way two members of the same species are differentiated…

…[F]or our imagined things A and B to differ as species do, we would have to regard being that which just is existence itself as a genus, and A and B as two species within that genus; and we’d then have to identify some “specific difference” that A has that makes it a different species of being that which just is existence itself from the species B. But the trouble is that if A has such a “specific difference”, then it will not be that which just is existence itself; rather, it will be that which just is existence itself PLUS that specific difference…

Consider now the way two members of the same species are differentiated… [T]hough Socrates and Plato are both human, they can differ because Socrates is humanity plus this particular bit of matter, whereas Plato is humanity plus that other particular bit of matter; and something similar can be said for the different members of other species. But then it should be obvious why we cannot differentiate two things A and B each of which is that which just is existence itself in the way that different members of a species are differentiated. For so differentiated, A and B will not after all be that which just is existence itself; rather, A will be that which just is existence itself PLUS this particular bit of matter, and B will be that which just is existence itself PLUS that other, particular bit of matter… (2017, pp. 120-121)

Is there a third possibility, perhaps? Could there be something for which existence is part of its essence, at least? But as Feser points out (2017, p. 122), that won’t work either: the existence of this being would then depend on its existence, making existence the true essence of this thing.

In general, Feser argues, in order for there to be more than one being which is Pure Existence itself, there would have to be something that made this instance of Pure Existence different from that instance. And then each such being would be a composite of Pure Existence PLUS some differentiating factor – in which case, it would no longer (contrary to our supposition) be Pure Existence.

What Feser’s argument manages to establish

Before I proceed to criticize Feser’s argument, I’d like to point out what he gets right. First, I think his argument that “existence” cannot be construed as a common genus is a cogent one; second, I think his argument that existence cannot be construed as a species is equally cogent. However, I dispute the inference that two entities belonging to the same genus (or for that matter, to the same species), cannot both be identical with their own individual acts of existence. That conclusion only follows if we assume, with Feser, that the term “existence” names a single perfection, which is inherently simple and unlimited. It is precisely this assumption which I think needs to be questioned.

An objection: Could a thing’s existence be composite?

|

|

Above: Busts of Socrates and Plato, kept in the Louvre museum and Capitoline museum. Images courtesy of Eric Gaba, Marie-Lan Nguyen and Wikipedia.

———————————

Feser neglects to consider the possibility that a thing’s existence may be composite. In that case, even if two things do belong to the same species or genus, each of them could still be identical with its own act of existence. For instance, consider two individuals, Socrates and Plato, of the same species (in this case, humanity). Socrates is humanity plus this piece of matter, M, while Plato is humanity plus that piece of matter, N. Humanity is their common form, but their essences as individuals are compounds of humanity plus M and humanity plus N, respectively. In that case, why should we not say that Socrates’ existence is likewise a compound of humanity plus M, while Plato’s existence is a compound of humanity plus N?

It seems to me that the reason why Feser is unwilling to entertain this possibility is because of his background metaphysical assumptions: he regards existence (or being) as a transcendental, without any limitations of its own. Because a thing’s existence, per se, is not limited or fragmented, Feser rejects the very notion of a thing whose existence is inherently composite, as unintelligible. His entire argument is predicated on the assumption that a thing’s existence is inherently simple. But it would be a mistake to draw this conclusion about the existence of individual things from the fact that the general concept of “existence” is not a complex one. Rather, what we should say is that “existence per se” is neither limited nor unlimited, and neither simple nor complex, but indefinite: it has no features of its own. As we’ll see below in section 7, this way of looking at things has some very significant implications regarding the classical concept of God.

A second objection: could two things whose essence is identical to their own existence be completely different from one another, like chalk and cheese?

|

|

There is another possibility which Feser has neglected to consider, in his argument. Even if one were to grant that no two things belonging to the same species or genus can possibly be identical with their own acts of existence, Feser has overlooked the possibility that two beings whose essences are identical with their own existence may not belong to any common category at all – be it a species, genus or whatever. Why should we assume that if there are two beings whose essence is identical to their existence, then they must belong either to the same species or the same genus? Why couldn’t they be as metaphysically different as chalk and cheese – or even more so, since chalk and cheese are both material substances?

Feser might reply that if there were two things, X and Y, such that X is identical to X’s existence while Y is identical to Y’s existence, then they must surely share something in common (“existence”), as well as having several distinguishing features, which would (a) fall outside the scope of “existence” (what are they then?) and (b) introduce composition into the X’s and Y’s natures, requiring them to have an external cause. But the underlying assumption of this argument is a flawed one: X and Y don’t need to share anything in common at all. They may not belong to any common species or genus; the resemblance between them may be purely analogical. For instance, we could say that an analogy of proportionality holds between them: the relation of X to X’s existence is the same as that of Y to Y’s existence (namely, that of identity).

===================================================================

Are there any other good arguments for a real distinction between essence and existence?

(a) Potency and act

In his Scholastic Metaphysics (editiones scholasticae, 2014), Feser puts forward several arguments for a real distinction between an ordinary thing’s essence and its existence, two of which are not covered in his more recent work, Five Proofs of the Existence of God (Ignatius Press, 2017). I’ll discuss these arguments briefly. The first argument is very straightforward:

The distinction between potency and act must, as the Thomist argues (for reasons set out in chapter 1), be a real distinction. But essence is a kind of potency and existence is a kind of act. Therefore the distinction between essence and existence is a real distinction. (2014, p. 242)

This argument is formally valid; however, I would contest its second premise. If it were indeed true that a thing’s essence is something which is able to be endowed with existence, then the distinction between the two would indeed be a real one. What I have been arguing is that this picture is false: what we should say instead is that neither a thing’s essence nor its existence are self-explanatory, and that the Cause of a thing’s nature (namely, God) is also the cause of its existence.

(b) An ontological argument reductio: why aren’t velociraptors real?

Feser asks: if a thing’s essence is the same as its existence, then why aren’t velociraptors real? Image courtesy of Dino Crisis Wiki and Artwork0.

Another argument for a real distinction between essence and existence, mentioned in passing by Feser, is that without such a distinction, it would follow that the essences of things not only exist, but exist necessarily, which is absurd:

If the existence of a lion, velociraptor or unicorn were not really distinct from its essence, then we should be able to argue, after the fashion of the ontological argument, that lions, velociraptors, and unicorns would exist necessarily rather than contingently, if they exist at all – which is absurd. (2014, p. 244)

This argument assumes that a thing’s essence is somehow necessary – for if it were not, then its existence would not be necessary, either. However, I see no reason to believe that essences are in any sense necessary. Indeed, on a theistic view, we can see why they must be radically contingent. For if essences originate as ideas entertained in the Mind of God (on the Scholastic realist view which Feser defends in chapter three of his book, Five Proofs of the Existence of God, when presenting his Augustinian proof of God’s existence), then it follows that if God had not chosen to entertain these ideas, they would have no reality whatsoever. To hold that these essences must be real in some sense is to hold that God necessarily has the ideas which he has, and that He has no control over the content of His ideas. Such a view is, to say the very least, contentious: it needs to be argued for.

Even if we were to suppose that God must have the concepts which He has, we could still explain why some essences (e.g. that of a velociraptor) are not currently instantiated, simply by invoking Aristotle’s form-matter distinction. On the Aristotelian-Scholastic view, things are not just forms, but composites of form and matter. Since God’s intellect contains the substantial forms of things, abstracted from their matter, it does not follow, from the mere fact that God understands what the form of a velociraptor is, that anything exists in Nature which instantiates this form. Only if God chooses to endow a piece of matter with this form will any velociraptors exist in Nature.

Finally, I might add that my earlier remarks on the incompleteness of our ideas of non-existent objects apply here, as well. Unicorns have no well-defined essences: our concept of a unicorn, like that of a winged horse or a phoenix, is only skin-deep.

An anti-Fregean argument by Feser

Cat on a fence. Image courtesy of Wikipedia. Feser argues that the question, “What makes it the case that there is anything which falls under the concept of being a cat?” is a meaningful one, and that it can only be answered by positing a real distinction between a cat’s essence and its existence.

In his book, Scholastic Metaphysics (editiones scholasticae, 2014), Feser puts forward an anti-Fregean argument in support of the claim that there is a real distinction between a thing’s essence and its existence:

There is, in any event, ample reason to doubt that the Fregean notion of existence captures everything that needs to be captured by an analysis of existence. Consider that when we are told that “Cats exist” means “There is at least one x such that x is a cat” or that something falls under the concept of being a cat, there is still the question of what makes this the case, of what it is exactly in virtue of which there is something falling under this concept. (2014, p. 253)

Citing the work of philosophers John Knasas and David Braine, Feser suggests that it is precisely in order to answer this question that we need to posit a real distinction between a cat’s essence and its existence: the latter is joined to the former as act to potency.

Let me begin by observing that even if Feser can demonstrate the falsity or inadequacy of the Fregean account of existence, this by no means establishes the truth of the Thomistic account which Feser is defending.

I would also add that I have no wish to defend the Fregean account as an adequate theory of existence. Personally, I have major reservations regarding such an account, as it seems incapable of even expressing what theists mean when they assert that there is a God.

In any case, it strikes me that Feser’s question, “What makes it the case that there is something falling under the concept of ‘being a cat’?” could be properly answered, simply by rephrasing the question as follows: “What causes cats to exist?” This is the sort of question which a scientist or a keen student of nature could answer, and it does not require us to conceive of cats’ essences having existence “poured into” them, like a bottle being filled with a beverage.

What I am proposing, in other words, is that Feser’s question appears puzzling only because of the form in which it is cast: it reifies the concept of “being a cat,” and then looks for a reason why some concepts are instantiated by one or more existent things, while others have nothing out there corresponding to them. But to construe the problem in this way is already to envisage concepts as inhabiting some shadowy, half-real world, waiting to have the fire of existence breathed into them. In short: ask a loaded question, and you’ll get a loaded answer.

Evaluation of Feser’s arguments for a real distinction between essence and existence

I conclude that none of Feser’s three arguments for a real distinction between a thing’s essence and its existence actually work. The first argument points to a form-matter distinction rather than an essence-existence distinction; the second establishes that contingent beings require an external cause, without showing that their natures are distinct from their existence; and the third demonstrates at most that if there are multiple beings whose essences are identical with their existence, then either the existence of these beings is something complex, or these beings resemble one another in a purely analogical fashion.

===================================================================

(f) Lack of logico-mathematical notation: a common flaw in all of Feser’s arguments

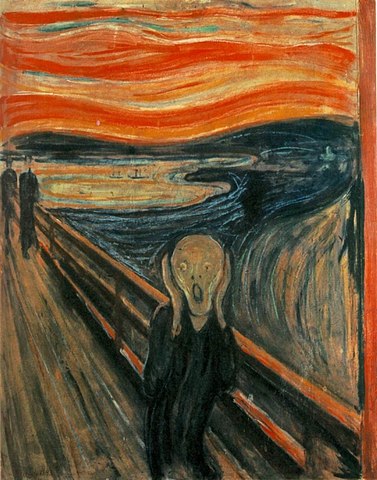

“The Scream,” by Edvard Munch (1893). National Gallery of Norway. Public domain. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

My reaction to all of Feser’s arguments for a real distinction between essence and existence can be illustrated by the painting above: they make me want to scream in frustration, because they are not formulated in the precise language of logic and mathematics. Arguments don’t have to be formulated that way, of course: but if you want the logic of your argument to be publicly checkable, then you need to express it in some kind of logico-mathematical notation. Otherwise what you get is two camps of philosophers shouting at one another: “But the conclusion of the argument is obvious! How can you be so blind as not to see it?” – “Doesn’t look at all obvious to us!” How is a layperson to adjudicate between these opposing camps? Clearly, we need an independent yardstick for assessing the validity of philosophers’ arguments. But in the absence of formal notation, we lack such a yardstick.

Now, Feser may protest, as he does in his book (2017, pp. 137-138) that the notation currently employed by most logicians presupposes a Fregean view of existence, which Thomists reject, as it treats existence as a second-order predicate of concepts, rather than as a first-order predicate of individuals. Very well, then: let him put forward a new, Thomistic notation, and use that to validate his argument. And yes, I do realize, of course, that Feser wants his book to reach as wide an audience as possible, and that lay readers may be turned off when they encounter logical notation in a book about the existence of God, but that is what appendices are for. Feser’s book is intended not just for laypeople but for everyone – layperson and scholar alike – and he needs to state his argument rigorously, in order to convince his more sharp-minded critics. (It may interest readers to know that a group of Polish Thomistic philosophers – known as the Cracow Circle – attempted a complete axiomatisation and formalization of Thomism, back in the 1930s. Here, for instance, is their attempted reconstruction of Aquinas’ First Way. So far, I have not been able to find any English translations of their works, online.)

Fortunately, Feser’s remarks on pages 137-138 on the factual statement, “Martians do not exist” (which he construes to mean, “Martians, which are of themselves existentially neutral, do not in fact exist”), provide us with a hint as to what kind of logical notation might suit Feser. In the tradition of Frege and Quine, the existential quantifier symbol (∃) means both “there is” and “exists,” but some logicians use another symbol, E!, to denote actual existence. Thus “Pterodactyls do not exist” (to use one of Feser’s examples) would then be written (∃x)(Px & -E!x), where P means “is a pterodactyl” and – means “not”: in other words, there are (existentially neutral) x’s [objects] which are pterodactyls and which do not actually exist.

===================================================================

(g) Formalizing and re-evaluating Feser’s arguments

Feser’s first argument can now be stated as follows: since I can know that (∃x)(Px) [there are pterodactyls] without knowing that (∃x)(Px & -E!x) [there are pterodactyls which really exist], it follows that P is not the same as E! [the predicate, “is-a-pterodactyl” is not the same as the predicate, “really exists.”] Feser’s second argument can then be stated in the following form: (∃x)(Lx & ◇-E!x), where “L” denotes “is a lion” and “◇” denotes “possibly” – in other words, there are some (existentially neutral) x’s [objects] which are lions and which are possibly non-existent, which again highlights the distinction between L (lionhood) and E! (actual existence). Feser’s third argument (insofar as it relates to specific differences between things) can be expressed by pointing out that for any two natural kind predicates F and G (say, “is-a-lion” and “is-a-pterodactyl”), if we were to suppose that F = E! and G = E! then it would follow that F = G, which is obviously false. So in general, we need to draw a distinction between a natural kind predicate and the actual existence operator E! See? That wasn’t so hard, was it?