In this post, I’ll be looking at chapter 6 of Dr. Edward Feser’s book, Five Proofs of the Existence of God, which deals with the nature of God, and I’ll be evaluating his arguments which purport to show that God is omnipotent, omniscient, good, capable of free choice and loving. I decided to begin by examining these “personal” attributes, because they’re the ones that really interest most people. Without these Divine attributes, any argument establishing that there exists an uncaused, fully actualized, necessary being, devoid of parts, whose essence is identical with its own act of existence could not be fairly called an argument for the existence of God, as such: it’s merely an argument for an Uncaused Cause.

My aim here is to evaluate Dr. Feser’s arguments in chapter 6, critically but fairly, in order to establish what they can tell us about God’s personal attributes, assuming that there exists an Uncaused Cause of the sort argued for by Feser in chapters 1 to 5 of his book. As we’ll see, Feser’s arguments for a personal Deity don’t prove much. All they establish is the following: (a) that everything depends on the Uncaused Cause, but not that it is capable of doing absolutely anything (or even anything which is consistent with its nature); (b) that universals exist in the Mind of the Uncaused Cause (a conclusion Feser argues for in chapter 3), but not that it actually knows any true propositions, let alone all true propositions; (c) that the Uncaused Cause is one-of-a-kind and free from defects, but not that it is benevolently disposed towards us; (d) that the Uncaused Cause is self-fulfilled and complete as a Being, but not that it is capable of free choice; and (e) that the Uncaused Cause brings about whatever is necessary for things to exist – whether it does so intentionally is another matter, however – but not that it cares about what happens to those things in the future, let alone that it cares about our future. After reviewing each section, I’ll discuss how Feser’s arguments could be strengthened, to make them more powerful. In addition, I’m going to throw in a bonus gift: I intend to show that Feser’s strong doctrine of the Purely Actual Actualizer (which he argues for in chapter 1) is false and untenable, before arguing that there is no need for classical theists to hold it: all they need to maintain is that God’s existence involves no actualization of potential (even if His activities do).

Before I continue, however, I’d like to quickly run through a few philosophical principles which Dr. Feser appeals to, in his arguments for God’s personal attributes. I’ll try to be as brief (a little over 1,000 words) and non-technical as possible. In what follows, I’ll be sparing you the trouble of reading Feser’s expositions of these principles, which are very thorough, but lengthy, and at times, difficult to understand. Hence the title: “Thomism without Tears.” Readers who really can’t stand metaphysics may want to skip over these principles and scroll down to the picture of the magnifying glass, and then scroll back up to them when they need to. Please note that I will not be attempting a proof of these principles here; that is a subject for a future post. Finally, all clarifying remarks below in square brackets are mine.

————————————————————————————————-

Philosophical Preamble: Thomism without Tears

1. The Principle of Causality (PC)

Many schools of philosophy invoke a principle of causality. However, the Aristotelian-Thomistic version of this principle (which is the one Feser appeals to) can be expressed as follows:

Everything that changes, or is composite, or that comes into being, has potentials that need actualizing, and therefore requires an external cause, distinct from itself, to actualize these potentials.

Notes:

1. The Principle of Causality (PC) does not say that everything has a cause. Something which never came into being, never changed, and wasn’t composed of parts, wouldn’t require a cause.

2. In Aristotelian terminology, the kind of cause we are talking about here is an efficient cause: something that brings about a state of affairs. This is what most people mean when they use the term “cause.”

3. On the Aristotelian-Thomistic formulation of PC, a cause need not be a determining cause. A cause which produces its effects indeterminately would be just fine: as Feser puts it, “For a cause to be sufficient to explain its effect, it is not necessary that it cause in a deterministic way” (2017, p. 51). Thus Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle poses no threat to PC.

4. Feser understands the term “cause” to mean: whatever actualizes a potential of some sort. Thus a thing which undergoes change and becomes F (where F denotes either a property [red, fat or rich] or a kind of entity [a frog or a water molecule]) is something that has the potential to be F; a thing which is composite has parts which have the potential to be brought and held together; a thing which comes into existence has an essence which has the potential to be endowed with existence. According to the principle of causality, all of these potentials require the action of something external to the thing in question, in order to realize them: a thing which is able to become red, or become a frog, requires something to make it red, or make it a frog; a thing whose parts are able to come together and remain together still requires something to bring those parts together and keep them together; a thing which comes into existence requires something to bring it into existence.

5. If may be objected that Newton’s First Law of Motion makes no mention of causes, or that quantum mechanics does away with causes at the submicroscopic level. Feser’s answer is that these are purely mathematical descriptions of reality, which make no attempt to capture the notion of a cause. Also, it is a mistake to think that events at the quantum level are uncaused, merely because they are unpredictable: radioactive decay (which is regarded as a purely random event) is nevertheless caused by the tunneling of a particle out of the nucleus, which in turn occurs because the particle is able to borrow energy from its surroundings: this borrowed energy can thus be described as the efficient cause of the nucleus’s decay. Likewise, virtual particles (which fluctuate into and out of existence over very short periods) do not arise out of nowhere, but out of the quantum field they are associated with; the field may therefore be called their efficient cause.

————————————————————————————————-

2. The Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR)

The Scholastic formulation of this principle (which is very different from the Leibnizian formulation) is as follows:

For anything which exists, there is an adequate explanation for its existence (i.e. its being) and for all of its attributes.

Notes:

1. The explanation of a thing’s existence need not be distinct from the thing itself; a thing could turn out to be self-explanatory. In this respect, an explanation is different from a cause, which is, by definition, distinct from its effect.

2. An “adequate explanation” of a thing’s existence need not be a set of necessary and sufficient conditions, as in Leibniz’s version of PSR; a set of conditions which are capable of producing the result will do.

3. On the Scholastic formulation of PSR, it is not propositions which require an adequate explanation, but things, or beings, and their attributes. The Leibnizian version of PSR, by contrast, relates to propositions: it states that “we can find no true or existent fact, no true assertion, without there being a sufficient reason why it is thus and not otherwise.” (G VI, 612/L 646)

————————————————————————————————-

3. The Principle of Proportionate Causality (PPC)

This principle is said to follow from the Thomistic version of the Principle of Sufficient Reason (which holds that everything which exists [i.e. every kind of being, not every proposition, as in the Leibnizian PSR] has a sufficient reason, either within itself or external to itself, which is adequate to explain its existence) and the Principle of Causality (which says that everything that changes, or is composite, or that comes into being, has a cause). Briefly, the PPC holds that the cause of an effect must possess something actual, whereby it is capable of producing the effect – in other words, whatever is in the effect must be in some way “in” the cause.

The cause of F-ness (e.g. redness, sadness, or wealthiness) in an effect may produce this F-ness in one of three ways: either by giving some of its own F-ness to the effect (in which case we say that the cause possesses F-ness formally), or by having some power to get hold of another entity’s F-ness and transfer it to the effect (in which case we say that the cause possesses F-ness virtually), or by simply having some power of its own to produce F-ness in the effect, without needing to give any from itself or borrow it from other entities (in which case we say that the cause possesses F-ness eminently).

————————————————————————————————-

4. Action follows being (in Scholastic jargon, agere sequitur esse)

A thing’s existence is more fundamental than its actions. Hence, a thing’s mode of action reflects its mode of being. In particular, a thing’s mode of acting cannot go beyond its nature.

————————————————————————————————-

5. The analogy of being

The term “being,” as applied to different kinds of things, is used analogically, rather than univocally (in the same sense) or equivocally (in totally different senses).

In our world, we observe many different kinds of beings. Since these different kinds of beings are neither identical as beings (for if they were, then what differentiates them would have to be non-being, and hence nothing) nor totally different from one another as beings (for if they were, they would have nothing in common at all), then they must share some resemblance to one another as beings. This resemblance is known as the analogy of being.

The resemblance which different kinds of beings share may be due to the fact that one kind of being is said to be the cause of another, in which case we describe it as analogy of attribution (e.g. when a certain food is called “healthy” because it causes health, in people who eat it); or it may be due to some intrinsic similarity between these beings, in which case we refer to it as analogy of proportionality. If this intrinsic similarity is between the natures (or forms) of these things, then it is called analogy of proper proportionality: for instance, microbes, plants and animals (including humans) are all said to be alive, because of something in their nature that makes them so; hence an analogy of proper proportionality holds between them. Otherwise, the intrinsic similarity is regarded as metaphorical: thus a courageous man may be called a lion, even though he does not possess the nature of a lion.

————————————————————————————————-

And now, without further ado, let’s take a look at Feser’s arguments.

1. God’s Omnipotence

I have to say that Dr. Feser’s section on omnipotence was disappointing. Whereas Feser’s discussion of omniscience is well-referenced, thorough and au fait with the contemporary literature, his section on omnipotence contains just one footnote, referencing two out-of-date articles dating back to 1963 and 1964. This is a significant omission, because a lot has been written on the subject since then, by philosophers such as Plantinga, Pike, Geach, La Croix, Rosenkrantz & Hoffman, Wierenga, Flint & Freddoso, Nagasawa, Wielenberg, Morriston, Oppy, Pearce, and Leftow, to name just a few. To make matters worse, Feser’s definition of omnipotence is vague and non-standard, and Feser frequently contradicts himself on the subject.

To be sure, Feser begins well enough. He argues that anything which is not God would have potentials that need to be actualized (e.g. parts that need to be held together), and would therefore require an external cause for its very existence, leading us back to God, the Uncaused Cause. (Feser has already argued that there can only be one such Being, a claim I shall discuss in a future post.) Next, Feser invokes principle number 4 above (a thing’s mode of action reflects its mode of being) to argue that if a thing is totally dependent upon God in its being, it must likewise be totally dependent on God in order to act. He concludes: “So if a thing’s essence gives it no capacity even to exist even apart from God, it cannot intelligibly give it power to act apart from God” (2017, p. 206).

What can an omnipotent being do, exactly?

Having established that every contingent being depends at every instant on God, not only for its existence, but also for its capacity to act, Feser adds that “there is nothing outside the range of his power,” which apparently means that “there is no potential he cannot actualize” (2017, p. 207). This, for Feser, suffices to define omnipotence: “to be that from which all power derives, and which has nothing outside the range of his power, is to be all-powerful or omnipotent” (2017, p. 206).

So it sounds as though Feser is saying:

(1) S is omnipotent =df S is: (a) the Uncaused Cause of all other beings’ existence and actions; (b) able to actualize any potentiality within these beings.

In other words, God’s omnipotence boils down to His ability to actualize any potentiality within the things He maintains in existence. This is an interesting definition, but problematic on two counts. First, it does not tell us whether God can actualize these potentialities immediately (without needing to go through other creatures), or whether He always acts through secondary causes. The Principle of Proportionate Causality (PPC) will not help us here: all it tells us is that God, as the Uncaused Cause of all effects, must possess something whereby He is capable of producing those effects. But if He causes these effects eminently, by having some power to produce these effects, he may do so either mediately or immediately.

Now, I realize that it may sound obvious to some readers that if God can directly produce A, and if A can produce B, then God can surely produce B directly, too. After all, wouldn’t it be strange if A possessed a capacity which God lacked? But the conclusion doesn’t follow. For God does not lack the capacity to produce B; He merely lacks the capacity to do so directly. I find nothing contradictory in this supposition, bizarre as it may seem to some.

Second, the definition does not tell us whether God is capable of actualizing any and every passive potentiality within creatures, or whether He is simply capable of activating any active power that they possess. The latter capability would mean that God can “start up” any natural agent He wants to, but it would not give Him unlimited power to realize creatures’ passive potentialities, because He may be only capable of producing effects through the things He has made, and there may be no proximate natural agent that can realize a creature’s passive potentiality for some quality. For example, the planet Neptune may have the passive potentiality to be heated to a temperature of 10 million degrees Celsius, but if there is no nearby star with the active capacity to heat it to that temperature (our Sun is obviously too small and too distant to perform the job), and if God only causes effects by acting through natural agents, then it will not be possible for God to heat the planet Neptune to 10 million degrees, after all.

In short: Feser’s definition of omnipotence may be interpreted either maximally (in which case, God can do pretty much anything he wants) or minimally (which would mean that He is incapable of going outside the order of Nature, and only capable of bringing about whatever it is that proximate natural agents have the power to bring about).

Feser’s contradictions

To make matters worse, Feser contradicts himself on what God can do. In the following passage, he appears to imply that God can bring about whatever is logically possible:

Can God do absolutely anything, then? That depends on what we have in mind by “anything”. If the question is whether God could cause to exist or occur anything that could in principle exist or occur, then the answer is that he can indeed do so. (2017, p. 207)

The problem with this view, as Kenneth Pearce points out in his article, Omnipotence in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, is that creating a stone which its creator cannot lift is a logically possible action: I’m quite capable of making a stone which I can’t lift, for instance. Another logical possible action is sinning – e.g by telling a lie, or breaking a promise. Yet on a traditional account of Divine omnipotence, God can do neither of these things.

Feser tries to circumvent this difficulty by proposing a more restricted definition of omnipotence: God can do any action which it is logically possible for God to perform:

… God cannot make a stone that is too heavy for him to lift any more than he can make a round square, and the reason is that there is no such thing in the first place as the capacity to make a stone too heavy for God to lift… As we will see below, God possesses perfect goodness, and thus cannot sin. But this is no more inconsistent with his being omnipotent than his being unable to create a round square is. For the notion of something that is perfectly good but also sins is, like the notion of a round square, self-contradictory. (2017, pp. 207-208)

A hypothetical individual nicknamed McEar, first proposed by Alvin Plantinga, poses problems for the definition of omnipotence.

But this restricted definition falls foul of a counter-example proposed in 1967 by Alvin Plantinga: a hypothetical individual named Mr McEar, who has the essential property of only having the power to scratch his ear, and who is incapable of doing anything else. (The name of this curious individual was not originally proposed by Plantinga, but subsequently, by La Croix, in 1977.) McEar is capable of doing the one and only action which it is logically possible for him to perform. On the restricted definition proposed above, he would be omnipotent! Of course, it may be objected that the example is an artificial one, but the point is that the revised definition of omnipotence proposed above may turn out to be quite restricted in scope.

A more sophisticated response, which Feser would presumably urge, is that McEar, unlike God, is not the Uncaused Cause of the cosmos. God can cause quite a wide range of effects, through His creatures, whereas McEar is a one-trick pony. But if acts performed by creatures are held to be things which God can do (albeit mediately), as their Ultimate Cause, then we shall have to say that a person’s sinning is an act of God, after all, and we are back at square one again.

A “possible worlds” approach to omnipotence?

It appears that the quest to define omnipotence in terms of the acts which an omnipotent Being can perform has stalled. Other philosophers have tried a different tack, attempting to define omnipotence in terms of the possible worlds that an omnipotent Being would be capable of bringing about. Perhaps we could define an omnipotent Being as a Being who is capable of bringing about any logically possible world (or none at all). The McEar objection simply does not arise within this theory, and the paradox of the stone is neatly deflected, as well, since there being a stone which an omnipotent being cannot lift is obviously not a possible state of affairs. Feser seems to be broadly sympathetic with this “possible worlds” approach, for he writes elsewhere:

Of course, given that agere sequitur esse [a thing’s mode of action reflects its mode of being], we would expect that a perfect being would have the capacity to create any of the infinite number of possible worlds. But that doesn’t entail it must in fact exercise that capacity in any particular way, or exercise it at all… (2017, p. 228)

The problem here is that Feser has not yet demonstrated that the Uncaused Cause possesses such a wide-ranging capacity: it needs to be argued for. Another problem is that the foregoing definition would imply that there is no possible world which is so hellish, pointless or irrational that a perfect Being could not create it. Feser himself appears uneasy with this definition, for he suggests that there would be something inappropriate about God’s creating trees “without also creating the things trees need in order to flourish – water, sunlight, and so forth,” as on that scenario, He “might be said to harm them” (2017, p. 227). And I presume that Feser would agree that God could not make a world contain two distinct species of rational animals, each of whom could obtain vital nutrients only by eating the flesh of the other, thereby necessitating cannibalism. There would be something irrational about God’s making a world like that, if He cared about rational beings as He ought to. One could attempt to circumvent this difficulty by redefining omnipotence as follows:

(2) S is omnipotent =df S can bring about any state of affairs p such that it is logically possible that S brings about p

However, adopting this definition would bring back the McEar objection, counting as omnipotent a being who can do nothing but scratch its ear. Philosophers have responded to this difficulty in various ways, some by arguing that the McEar objection is simply ridiculous (e.g. Wierenga, who argues that if McEar has the power to scratch his ear, then he also has the power to move a part of his body to scratch his ear, say, his arm, so the notion of an omnipotent being having only a single power is absurd), others by giving up on the attempt to define omnipotence, and still others, such as Flint and Freddoso (1983), by proposing a definition in terms of maximal power: roughly, an omnipotent agent can actualize any state of affairs that it is possible for someone to actualize, except for certain “counterfactuals of freedom”, their consequents, and certain states of affairs that are “accidentally impossible” because of the past. (Freddoso, by the way, was one of the philosophy professors who reviewed Feser’s book.)

Hoffman and Rosenkrantz discuss Flint and Freddoso’s definition in their article on omnipotence in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, and present a possible counterexample, in addition to putting forward their own alternative definition of omnipotence, which stipulates that an omnipotent being should only be required to bring about states of affairs that are repeatable without restriction, and that don’t contain any components whose repeatability is restricted. Hoffman and Rosenkrantz’s definition is a promising one, and the scholarly debate over definitions omnipotence will doubtless continue for decades to come. Sadly, Feser never even alludes to the scholarly debate which has taken place over the last fifty years, in his discussion of omnipotence. Were he writing a book intended purely for the layperson, this lapse would perhaps be understandable, but his aim, as he declares in his Introduction (2017, p. 15) is a bold one: namely, to show that none of the objections against natural theology succeeds. The only way to do that is to address these objections in depth, including objections to the very notion of omnipotence.

To sum up: all Feser has shown so far is that everything depends, for its being and actions, on the Uncaused Cause, and that this Cause is capable of activating natural agents in order to bring about effects. However, Feser has not demonstrated that this Uncaused Cause is capable of doing absolutely anything which is logically consistent (or even anything which is which is consistent with its nature), or that the Uncaused Cause is capable of creating any possible world (or even any possible world consistent with its nature). Nor has he proposed a more sensible restricted definition, which circumvents the difficulties relating to the definition of omnipotence which I listed above.

————————————————————————————————-

2. God’s Omniscience

The cat sat on the mat. Courtesy of Frederick French.

Feser defines omniscience as the possession of all knowledge. God knows all propositions about Himself and everything else (2017, p. 211), but in a unified way: He grasps things of various kinds by understanding how the various modes of being actualized in a limited way (i.e. as a finite creature) can all be derived from His infinite nature (2017, p. 216). And he knows what happens in the world by knowing His own thoughts and intentions as the Author of the cosmos, who brings about whatever takes place in the world (2017, p. 212).

In chapter 3 of his book, Feser marshals an impressive array of arguments for the reality of universals, against nominalists and conceptualists, who deny their reality. He then argues that if they are real, they can only exist in concrete objects, or in somebody’s intellect, or in some Platonic realm, and he then proceeds to rule out the third option, before arguing that some timeless universals cannot plausibly be said to exist purely in concrete objects – which means that they must exist in a timeless Mind. I will discuss Feser’s Augustinian argument in chapter 3 of his book, in a future post.

Feser’s argument that God’s intellect contains all concepts

In chapter 6, however, Feser invokes the Principle of Causality (PC) to argue that “anything that exists or could exist, and anything that anyone does or could do, depends at every moment on God’s causal action” (2017, p. 208). That includes things’ properties (redness, roundness and so on): God must cause these properties to exist in things. Feser then invokes the Principle of Proportionate Causality (PPC) (whatever is in the effect must be in some way “in” the cause), to argue that “in some way or other, colors, sounds, shapes, sizes, spatial locations, atomic structures, chemical compositions, surface reflectance properties, nutritive powers, locomotive capacities, and every other feature of everything that exists – whether mineral, vegetable, animal, human, or angel – must exist in God” (2017, p. 208), as their Ultimate Cause. But if God is their Ultimate Cause, then God cannot instantiate these properties Himself (in the way that concrete objects do) – for then His own possession of these properties would require an explanation, too. Since they must exist in God in some way, and since they cannot exist in a concrete way or in some Platonic “third realm,” it follows that these universals exist in God “as concepts or ideas in an intellect,” which means that “we have to attribute intellect to God” (2017, p. 209).

But having an intellect and having knowledge are two very different things, as Feser himself acknowledges. Feser writes: “[O]n the standard philosophical account of knowledge, one knows some proposition p when (a) one thinks p is true, (b) p really is true, and (c) one thinks p is true as a result of some reliable process of thought formation” (2017, p. 210). Knowledge, in other words, is typically of propositions (although we can also speak of knowing how to do something), but all that Feser claims to have established at this point is that God possesses concepts.

Feser’s proof that God knows all propositions

So, how does Feser argue that God knows all propositions, or indeed, any propositions at all? First, he invokes the Principle of Proportionate Causality (PPC) to argue that God’s causation of all states of affairs that occur in the cosmos implies that the propositions which describe those states of affairs must exist in God’s intellect:

Consider a cat sitting on a mat. That the cat and the mat exist at all at any instant at which they do exist is due to God’s causal activity. But that the state of affairs of the cat’s being on the mat holds at any instant is also due to God’s causal activity. So just as, given the principle of proportionate causality, the “catness” of the cat must exist in God at the concept catness, so too must the state of affairs of the cat’s being on the mat in some way exist in God. In particular, it must exist as the proposition that the cat is on the mat. For just as the concept catness is the correlation within an intellect of the universal form or pattern catness that exists in actual cats, the proposition that the cat is on the mat, considered as the content of a thought, is the correlate within an intellect of the state of affairs of the cat’s being on the mat. And just as the concept of anything that might exist would have to be in God’s intellect, so too must the propositions corresponding to any state of affairs that might obtain as thoughts in the divine intellect, since these states of affairs can obtain only insofar as God causes them to.

Naturally, among the states of affairs that obtain are the state of affairs that the proposition that the cat is on the mat is a true proposition, and the state of affairs that the proposition that unicorns exist is a false proposition. So, thoughts corresponding to these states of affairs will be among those in the divine intellect. That is to say, there is in the divine intellect the thought that it is true that the cat is on the mat, the thought that it is false that unicorns exist, and so forth. Furthermore, since everything that exists or might exist other than God , and every state of affairs that obtains or might obtain other than God’s existence, depends on God’s causal activity, all propositions about such things will be true or false only because God causes the world to be such that these propositions are either true or false.

However, there are two fatal problems with Feser’s invocation of the Principle of Proportionate Causality (PPC) in order to demonstrate that God’s intellect contains propositions corresponding to all states of affairs that obtain. First, the PPC states that the cause of an effect must possess something whereby it is capable of producing the effect. But propositions don’t cause anything: they are causally inert. Therefore a proposition in God’s intellect cannot possibly explain the cat sitting on the mat. One might attempt to remedy this difficulty by suggesting that the proposition in God’s intellect that the cat is on the mat, coupled with an act of will on God’s part that there should be a cat on the mat, would suffice to explain there being one. But Feser has not yet presented his argument that God even has a will – and as we’ll see, the argument which he does present is a flawed one.

Second, the Principle of Proportionate Causality (PPC) is said to follow from the Thomistic version of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, coupled with the Principle of Causality (2017, p. 170). However, according to the Thomistic version of the PSR, it is not propositions which require an adequate explanation, but beings, and their attributes. As Feser puts it in his Scholastic Metaphysics, “on the Scholastic understanding of PSR, propositions are not among the things requiring explanation in the first place, and explanation does not require logical entailment” (2014, editiones scholasticae, p. 141). But if propositions do not require explanation, neither do states of affairs as such: it is beings and their properties that require explanation, according to the Thomistic version of PSR. Perhaps God intentionally causes there to be a cat, and causes there to be a mat, without intentionally causing there to be a cat on the mat.

A note about Feser’s overall strategy

Observant readers will have noticed the argumentative strategy which Feser is adopting here. Having previously established to his own satisfaction that God somehow possesses universals, but without materially instantiating them, Feser concludes that these universals must reside as concepts in the Divine intellect, since there is no other way in which they could exist outside of matter, barring existence in a Platonic “realm of forms,” which Feser rejects as nonsensical. Feser then attempts to establish that God’s intellect contains all propositions relating to the states of affairs which it causes, concluding that He must know everything about the world.

For my part, I regard such a strategy as fundamentally misguided. Following Wittgenstein, I hold that propositional thought is essentially linguistic. Since knowledge (in the paradigmatic sense of “knowledge that,” as opposed to “knowledge how“) is essentially propositional, it follows that there can be no knowledge without a language of some sort. Thus, before we can prove that God possesses any knowledge at all (let alone a knowledge of everything happening in the world), we need to first show that God is capable of language.

Nor can we appeal to concepts as proof of God’s intellectual capacity, without first addressing the question of whether God is capable of language. For it is a mistake to try to define intelligence in terms of an ability to “receive” abstract universal forms, or to “contain” these forms, or to be in “immediate contact” with these forms, or to “extract” these forms, or to “grasp” these forms. Receiving, containing, touching, extracting and grasping are not rule-following activities as such. They are spatial metaphors for intelligence, but they do not capture its very essence. To entertain a concept of a certain kind of thing is, I would suggest, to follow a rule which defines how we are to think about that kind of thing. None of the commonly used spatial metaphors for intelligence can capture the act of following a rule. But rules can only be expressed in the medium of language. No language, no intellectual concepts. (I don’t wish to discuss the question of to what degree concepts can be ascribed to non-human animals

So how might we establish that God is capable of language? One very powerful hint that He possesses such a capability is that the laws of the cosmos are written in the language of mathematics – and very beautiful mathematics at that. (I have written more about this subject in my 2011 Uncommon Descent article, Why the mathematical beauty we find in the cosmos is an objective “fact” which points to a Designer.) Another hint is suggested by our own capacity for language, which defies explanation in reductionistic terms.

Does God know what He causes?

Next, Feser argues that God meets each of the conditions for knowing those propositions that He causes to be true, according to the standard philosophical account of knowledge:

Again, consider the proposition that the cat is on the mat. We have seen that there must be in the divine intellect the thought that it is true that the cat is on the mat. So condition (a) obtains [i.e. God believes or thinks that the proposition is true]. And it really is true that the cat is on the mat, precisely because God is causing that to be the case. So, condition (b) obtains [i.e. the proposition really is true]. Furthermore, there can be no more reliable way of determining whether some proposition p is true than being able to make it the case that it is true… So, since the cat is on the mat only insofar as God himself causes it to be the case that the cat is on the mat, God certainly has a reliable way of “finding out” whether such a proposition is true. So condition (c) obtains [i.e. God believes that the proposition is true as a result of some reliable process for generating true beliefs]. So, God has knowledge. (2017, p. 211)

Notice Feser’s remark above that “there can be no more reliable way of determining whether some proposition p is true than being able to make it the case that it is true.” This is problematic on two counts. First, it only holds if the agent making it the case that the proposition is true, does so in a deterministic manner. But as Feser expressly declares in his discussion of the principle of causality, “from an Aristotelian point of view it is a mistake to suppose in the first place that causality entails determinism” (2017, p. 51). Second, a causal agent’s act of determining some proposition to be true, does not normally make the agent believe that the proposition is true, as the third condition in the standard account of knowledge stipulates. All causal agents which act in a deterministic manner determine some proposition (corresponding to the state of affairs they bring about) to be the case: for instance, when the Earth make an apple fall, it determines the proposition describing the apple’s fall to be true. Yet the Earth knows nothing about this fact. It is only causal agents which act intentionally (i.e. rational agents) who come to believe that a proposition is true as a result of determining it to be true. However, Feser has yet to show that God acts in this manner, as he has not yet discussed God’s will.

Finally, I should point out that Feser makes no reference in the passage cited above to the problem of deviant causal chains in accidentally generating true beliefs. That is because his account of knowledge makes no reference to the unresolved Gettier problem – a surprising omission in a discussion of this nature. Of course, there have been suggestions put forward by philosophers regarding how to fix these deviant causal chains – for instance, by adding an Appropriate Causality Proposal (Goldman, 1967). However, as many of my readers are well aware, these suggestions run into problems of their own: the term “knowledge” is notoriously difficult, if not impossible, to define.

God’s Self-Knowledge

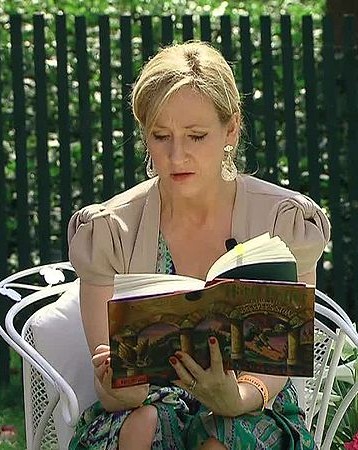

The acclaimed children’s author J. K. Rowling, reading a passage from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone at the Easter Egg Roll at the White House in 2010.

Feser then goes on to argue that God also has a complete knowledge of Himself, by appealing to the metaphor of God as the author of a story. Moreover, unlike a human author, God has no parts, which would limit his knowledge of Himself:

Moreover, he [God] can hardly have less knowledge about himself than he has about things other than himself, any more than an author can know less about his own creative act of coming up with a story then he knows about the story itself…

Now, if God has knowledge of all propositions about himself and everything else, then he has all knowledge. He is omniscient. (2017, p. 211)

However, Feser’s assertion that God can hardly have less knowledge about Himself than He has about His creation is a purely rhetorical one, for which Feser presents no argumentation. Certainly, the metaphor of God as an author who “comes up with a story in a single, instantaneous flash of insight” (2017, p. 210) is a deeply appealing one, which would resolve the difficulty alluded to above, concerning deviant causal chains: an author’s beliefs about the characters in his story are generated by his own intentions, so no deviant chains can arise. The storybook metaphor also circumvents difficulties relating to the reliability of God’s knowledge (condition (c) in the standard philosophical account of knowledge as justified true belief): because an author intentionally determines the course of his story, his beliefs about the course of the story are infallibly reliable. However, Feser presents no argument for the aptness of this metaphor, when applied to God. The omission is a significant one, as Feser, like other Thomists, appeals to just two kinds of analogy (see note 5 above) in order to secure the meaningfulness of the things we say about God: analogy of attribution (where God is described as the cause of various perfections existing in creatures) and analogy of proper proportionality (where He is said to be intrinsically similar in nature to His creatures). Metaphorical analogies are a hit-and-miss affair: they may or may not be suitably applied to God. And as readers of my previous post will be aware, the notion that God is like the author of a story runs into all sorts of difficulties, relating to human freedom. If He is indeed the author of a story, then it has to be a story like no other: an interactive one, in which the characters can communicate with the author and affect the outcome. And on such an account, since we have granted the characters the ability to defy the intentions of their author, we can no longer argue (as we did above) that because God intentionally determines the course of world history, His beliefs about it are infallibly reliable. Instead, we would have to suppose that God creates things in such a way that they automatically provide Him with instantaneous (and timeless) feedback about whatever happens to them, making God a Divine observer of human affairs. But this Boethian account of God’s foreknowledge is one which Feser considers and forcefully rejects in his book (2017, p. 212), for reasons which turn out to generally unconvincing: (a) God has no perceptual organs (true, but God’s being informed does not require Him to have a body); (b) God is outside time (true but there is nothing to prevent God from being informed timelessly about His creatures’ actions); (c) if God could view the past, present and future at once, they would have to be simultaneous (false, as God’s ability to see events A, B and C outside time doesn’t imply that the events themselves are outside time); and (d) in any case, God’s knowledge of the world is a consequence of His knowing His own decisions (an argument which begs the question).

In any case, the storybook metaphor fails to guarantee God’s self-knowledge, even when applied to a Being devoid of parts. All it guarantees is that God knows His ideas and creative acts: it says nothing whatsoever about His knowledge of Himself, in His innermost essence. Perhaps Feser could best remedy this difficulty by arguing that because we already know that God has an intellect (on the basis of arguments supplied in chapter 3), and because we also know that God is simple (for reasons Feser discusses in chapter 2 of his book, as well as on pages 189-196), it would then follow that God is an intellect, in which case, He cannot fail to know Himself. That would be a better approach, in my opinion.

A Non Sequitur

Feser also briefly mentions his argument in chapter 3, which “began with the thesis that God is an infinite intellect and then argued that such an intellect must have all knowledge” (2017, p. 211). However, this kind of reasoning trades on an ambiguity in the term “infinite intellect.” If the term means “an intellect with an infinite capacity,” then it does not follow that this intellect knows anything at all. For all we know, it may know nothing, even though it is capable of knowing everything. But if “infinite intellect” means “an intellect with an infinite amount of knowledge,” then Feser is assuming precisely what he needs to prove. (I should add that an infinite amount of knowledge is not the same as “all knowledge,” in any case. A being which knew the square of every integer would have an infinite amount of knowledge, but it would not thereby know everything.)

Summary

I conclude, then, that Feser’s argument for God’s omniscience is incomplete. Feser has failed to establish that God knows any true propositions – such as that there is a cat on the mat – about the world, let alone propositions relating to the choices we make. For all we know, God might know nothing about us. Of course, Feser can argue that God necessarily possesses self-knowledge if He is a pure and simple intellect; however, such an argument presupposes the doctrine of Divine simplicity.

————————————————————————————————-

3. God’s Goodness

Feser begins by attempting to set the notion of goodness on an objective footing, before going on to define moral goodness as a special kind of goodness, which is found only in rational creatures who can choose either to realize or to frustrate their natural potentials:

In order to see that God must be perfectly good, we need first to understand what goodness and badness are…

The sense of “good” and “bad” operative here is the one that is operative when we speak of a good or a bad specimen, a good or bad instance of a kind of thing. It has to do with a thing’s success or failure in living up to the standard inherent in the kind of thing it is. And this notion of goodness and badness applies to everything, since everything is a thing of a certain kind. Goodness and badness can be defined objectively… Moral goodness and badness enter the picture with creatures capable of freely choosing to act in a way that either facilitates or frustrates the actualization of the potentials which, given their nature or essence, they need to realize in order to flourish. (2017, p. 218)

However, on the definition just given, it seems that we cannot call God morally good, as He has no unrealized potential, and therefore cannot be said to act in a way that facilitates the realization of His potential. As Feser himself puts it elsewhere: “God does not have to do anything to realize his nature, since he is always and already fully actual” (2017, p. 224).

Feser could resolve this difficulty by arguing that on the contrary, there is something which God timelessly needs to do in order to realize His nature, namely: those activities which characterize Him as God. Since God is Pure Act, then He can appropriately be described as Pure Doing. However, in order to demonstrate that God is morally good, Feser would also need to demonstrate that God acts freely, as befits a rational agent. Unfortunately, Feser does not attempt such a proof until the following section, on God’s Will, and as I shall argue below, Feser’s proof is unsuccessful.

Additionally, Feser contends that goodness is more fundamental than badness (or evil), as the latter can only be defined as a privation of the former:

Now, note that goodness involves being actual in a certain way, again, in a way that involves realizing what is implicit in the nature or essence of a thing. A triangle is good to the extent that its sides are actually straight, a tree is good to the extent that it actually sinks roots into the ground and carries out photosynthesis, and so forth. Badness, meanwhile, involves a failure to be actual in some way – again, in a way that involves failure to realize what is implicit in the nature or essence of a thing. A triangle is bad to the extent that its sides are not perfectly straight, a tree is bad to the extent that its roots are weak, or it fails to carry out photosynthesis, and so on…

Goodness and badness, then, are not on a metaphysical par. Goodness is primary, since it is to be understood in terms of the presence of some feature. Badness is derivative, since it amounts to nothing more than the absence of some feature, and in particular the absence of goodness of some kind or other. Goodness is a kind of actuality, and badness a kind of unrealized potentiality. To be bad in some respect is, ultimately, to lack something rather than to have something, just as to be blind is simply to lack sight rather than to have some positive feature…

…Now, we have seen that God is purely actual, with no potentiality. But if actuality corresponds to goodness and badness to unrealized potentiality, then we have to attribute to God pure goodness and the utter absence in him of any sort of badness or evil. (2017, pp. 218-219, 221)

It will be seen here that Feser subscribes to the privation theory of evil, which he defends very vigorously and ably in his book. I have no quarrel with Feser on this point, as I think he answers the philosophical objections that have been marshaled against the theory quite convincingly. Sadistic desire, for instance, may seem to be a positive evil, but Feser argues that it is analyzable as “a desire that is misdirected, directed toward an end contrary to the concern for others which we need cultivate in order to flourish as social animals.” Thus it involves “a psychological deformity or defect, just as blindness involves a physical deformity or defect” (2017, p. 221). Pain may seem to be obviously evil, but it serves the biologically useful function of indicating that there is something wrong with the organism. Pain also disturbs our tranquility of mind, but it is this disturbance, rather than the pain itself, which is evil in itself, properly speaking.

While Feser makes a strong case that God is the Ultimate Good, in the passage cited above, his proof stops just when it is starting to get interesting: he fails to specify the nature of God’s goodness, except for a vague appeal to the Principle of Proportionate Causality (PPC), which entails that “whatever good there is or could be in the world must in some way be in God” (2017, p. 221). But if God possesses moral goodness in a merely “eminent” fashion (instead of possessing it formally, or virtually), that would simply mean that He is able to produce it in creatures, but without needing to impart any moral goodness from Himself, or borrow it from other entities. Is it really enough to say that God can make rational agents morally good, without imparting to them any moral goodness of His own? Or does this make God too anemic a Deity for us to worship?

To sum up: my chief objection to Feser’s account of God’s goodness is that it is too generic. In particular, it says nothing about love – although it does not rule it out, either. On Feser’s account, to call God good is simply to call Him metaphysically complete. The question I would ask is: if God is pure actuality, as Feser contends, then what kinds of acts can be said to characterize Him as a Being? These are the acts that make God good. We need to know more about them.

————————————————————————————————-

4. God’s Will

The lion and the unicorn, on the Royal coats of arms of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as used by Queen Elizabeth II. Feser holds that God could have created a world with lions or a world with unicorns, and that He freely chose to create the former.

Surprisingly, Feser’s treatment of God’s will is perhaps the weakest section of chapter 6 of his book. He begins by proposing a general definition of will as rational appetite, or a tendency towards some good which one apprehends to be worth pursuing, on the basis of one’s concept of the good in question. Having previously established that God has concepts, Feser is now able to apply this definition to God Himself, but immediately runs into a difficulty, which he acknowledges up-front: “God does not have to do anything to realize his nature, since he is always and already fully actual.” (2017, p. 224). Feser responds to this difficulty by suggesting that God’s completion is “the limit case to which the appetites we see in plants, animals, and human beings point”:

But in this he [God] is more like something which has completed the realization of his nature than he is like something which never tended or inclined towards such realization in the first place. We might say that there is in him something like the limit case of rational appetite. [In a footnote, Feser explains that a limit case is fundamentally different from that of which it is a limit: thus the complete absence of a tendency to pursue the good, because one does not need to do so, is not at all the same as a tendency to pursue the good, however slowly.] (2017, p. 224)

But the notion of a limit case is a fudge: it simply omits the core concept of what a will is. If having a will means having a tendency towards some good apprehended as worth pursuing, and if God has no such tendency, then surely the correct conclusion to draw is that He has no will, because He doesn’t need one.

A better line of argument would have been for Feser to maintain that God does, in fact, do something to realize His ultimate good: He unceasingly knows and loves Himself. Surely knowing and loving count as actions. In that case, we could truly say that God possesses a will, after all. In order to establish this conclusion, however, Feser would first need to show that God loves us.

Does God have free will?

Feser then proceeds to argue that at least with respect to His dealings with creatures, God possesses something that could be called a will, and that He must possess free will as well:

… God apprehends all the things that could exist, and causes some of those things actually to exist while refraining from causing others of them to exist. Hence, there must exist something in him analogous to willing the former and not willing the latter.

God’s will must also be free. For one thing (and as we have seen), everything other than God depends on God for its existence and operation at every instant at which it exists or acts. So, there cannot be anything external to God which somehow compels him to act as he does. For another thing (and as we have also seen), all possibilities are grounded in the divine intellect, and what actually exists pre-existed in God as an idea of concept of something which he might create… Before creation, then, a world with unicorns in it was [just] as possible as a world with lions in it. Given his knowledge of the possible thing he might create, God could have created either one. So, there was nothing internal to him which compelled him to create lions and not unicorns. But if there is nothing external to God or internal to him compelling him to act as he does, then his will is free. (2017, pp. 224-225).

Feser seems to be arguing here that apprehension plus causation implies the existence of will. On this point, I think he is mistaken. As I argued above, apprehension of a concept is a very different thing from knowledge of a proposition, and the former does not necessarily imply the latter. I also argued that Feser had failed to demonstrate that God possesses any knowledge of the world at all. In the absence of knowledge, in the proper sense of the word, we cannot meaningfully speak of God as possessing a will.

However, the foregoing passage has a much more serious consequence for Feser’s philosophy: it disproves one of his key concepts of God, as the Purely Actual Actualizer.

The Death of the Purely Actual Actualizer

Gravestone, courtesy of Mortal Engines wiki.

The fatal flaw here, for Feser’s doctrine of God as the Purely Actual Actualizer, is that in creating one world and not another, God is realizing one potentiality available to him (the possibility of a world with lions) and not another (the possibility of a world with unicorns). Hence if God is free, then He is not purely actual, after all.

Feser is well aware of this difficulty, and vainly attempts to evade its force, by pulling the “mystery” card and by mistakenly conflating the notion of actualizing a potential with the notion of change:

It is sometimes claimed that God’s will could not be free given the doctrine of divine simplicity. For to act freely entails (so the objection goes) that one has the potential to act one way rather than the other, and that one goes on to actualize one of these potentials rather than the other. But according to the doctrine of divine simplicity, God is purely actual and lacks any potentiality. Hence, he must not be free. Or, if he is free, he must after all have potentialities and must therefor not be absolutely simple or noncomposite.

However, it is simply not the case that free action entails the having and actualization of potentials. It is true that when we freely will to do one thing rather than another, we actualize various potentials (for example, the potential to move a limb in this direction rather than that one). But to conclude that all free action as such must involve the actualization of potentials would be to commit a fallacy of accident, just as (as we saw above) to suppose that all action involves change involves a fallacy of accident.

…As Brian Davies notes, it is easier to understand the assertion that God’s will is free as a claim of negative theology – to the effect that God is not compelled to act by anything external or internal to him – than as a claim with positive content… We know, from the considerations adduced above, that God must be both absolutely simple and free, and we know also that we should expect that his nature will be extremely difficult to grasp. That the freedom of the divine will is mysterious to us is hardly surprising, and hardly by itself a serious objection to the claim that God is both simple and free. (2017, pp. 225-226)

In the above passage, Feser denies that free choice entails having and actualizing potentials, despite having previously affirmed precisely that of God: he writes that “given his knowledge of the possible thing he might create, God could have created” either a world with lions or a world with unicorns (2017, p. 225). In other words, God had at least two options, which means that there were two potentialities available for Him to realize. Indeed, Feser goes further: on page 228, he writes that “a perfect being would have the capacity to create any of the infinite number of possible worlds,” as well as the capacity to create none at all. The potentialities here are infinite!

Nor do we need to think of God as changing, in any way, when choosing to realize one potential rather than another: we can simply say that God timelessly chooses to actualize world A (containing lions) rather than world B (containing unicorns). It is indeed a fallacy to suppose that all action involves change, but that has nothing to do with the point we are considering here.

Finally, Feser’s assertion that defining freedom in terms of actualizing potentials involves a fallacy of accident is incorrect. For a free choice must, by definition, involve two or more alternatives. No alternatives, no choice.

Feser frequently appeals to the metaphor of God as being like the author of a story, in his book. But it is this very metaphor which crushingly refutes his claim that choice need not involve actualization. For the very choice of becoming an author is itself an actualization of the author. When someone chooses to become an author, he actualizes himself in a way in which he would not be actualized, if he were to choose otherwise, and refrain from writing a book. And it makes no difference here whether the choice is made in time (as with human authors) or timelessly (as with God). The point still stands.

A more modest proposal: God as the Being Whose essence is totally actual, and in no way actualized by anything else

The conclusion that God actualizes Himself in an additional way by freely choosing to create this world is therefore inescapable. This extra actualization in no way adds to God’s essence, so one might think that Feser would find it unproblematic. But Feser argues elsewhere (2017, p. 185) that this additional actualization would entail that God has parts: in this case, His essence plus His choice to create this world. And that, argues Feser, would mean that God requires an outside cause to hold Him and His choice together – which means that God isn’t really God (the Uncaused Cause), which is absurd. But the argument Feser puts forward here is a sloppy one. He provides no definition of the term “part” in his entire book. Moreover, Feser’s claim that things composed of parts require an external cause to keep them together as one unit, makes sense only when both parts are ontologically prior to the unity they comprise. And in the case of an author and his choice, or a thinker and his thought, this condition clearly does not hold – for a thought is, by definition, ontologically posterior to the thinker that generates it, just as a choice is posterior to the agent that makes it. The reason why my thoughts and my choices do not float away from me is that they are generated by me: no external agent is needed to bind them to me.

I might add that despite Feser’s insistence that divine simplicity is “a binding doctrine” (2017, p. 190) of the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) and the First Vatican Council (1869-1870), if we examine these doctrinal declarations carefully, it turns out that the doctrine of Divine simplicity applies only to the essence of God: thus the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) speaks of God as having “one essence, substance, or nature absolutely simple.” There is nothing in this declaration to preclude God having thoughts or choices relating to creatures, as additional, non-essential properties. Interestingly, Eastern Orthodox theologians commonly distinguish between God’s essence and His operations, or energies – a view which has never been condemned by the other branches of Christendom. Thus it seems that there is nothing to prevent God’s operations from being multiple, even though His essence is simple.

I conclude that Feser’s doctrine of God as the Purely Actual Actualizer is stone dead, and there is no good reason to want such a doctrine to live. The more modest and conservative doctrine of God as the Being Whose essence is totally actual, and in no way actualized by anything else, is quite sufficient to put God in a league of His own.

————————————————————————————————-

5. God’s love

The section on God’s love in Feser’s book is surprisingly short: less than a page. Much of this section is spent explaining what God’s love is not: it does not mean that God is affected by what He loves, for that would imply a change in God, Who is immutable. Love, writes Feser, is not a matter of feelings, but of the will: “what is essential for love is that the lover will what is good for the beloved” (2017, p. 228). Feser then proceeds to argue for God’s love as follows:

Now as we have seen, there is will in God, and his will is directed toward the creation of the world. We have also seen that to be good is to be actual in some way. But to create things is to actualize them, and thus to bring about all the goodness that follows from that actuality. For example, to create trees entails willing that trees exist, and thus willing what is good for trees – their having roots that take in water and nutrients, their carrying out photosynthesis, and so forth – also exists. In that sense, that God creates things entails that he loves them. So, we must attribute love to God. (2017, p. 229)

Feser’s argument, as far as I can make out, seems to be as follows:

1. God wills the creation of things – in other words, He wills that certain kinds of things (e.g. trees) should exist.

2. To will the end is to will whatever is required to achieve that end.

3. To will the existence of things, as an end, is to will whatever goods are required, in order for those things to exist (e.g. soil and sunshine for trees).

4. To will what is good for a thing is to love that thing.

5. Hence God loves the things He creates.

Two obvious criticisms can be made of this argument. First, it doesn’t establish conclusively that God loves things as individuals; all it shows is that He loves them generically. God may love trees, but does He love the General Sherman tree (pictured above)? In order to establish that, one would have to show that God wills (i.e. intends, as opposed to merely foreseeing) the existence of each and every thing in the cosmos. The same goes for human beings: God may have decreed, “Let us make man in our own image,” but did He decree the coming into existence of each of the 108 billion people estimated to have ever lived?

Second, even if it could be shown that God loves individuals, all the argument shows is that God wills what is good for them, up until now. We have no assurance whatsoever that God wills the continuation in existence of these individuals – or even the species which they belong to. Most of the species that have lived on this Earth have died out, and to make matters worse, scientists tell us that at some point in the distant future, when the Sun swells to become a red giant, the last living thing on Earth will die. Hence we know that God doesn’t will trees to continue flourishing forever, even generically. Worst of all: what is to stop God, as the Author of the cosmos, from bringing down the curtain on creation earlier than that – say, tomorrow? Nothing, as far as I can tell.

Finally, even if God wills the creation of certain things (or kinds of things), it does not follow that He wills them as ultimate ends: He may will them only insofar as they contribute to some “greater good.” For instance, God may will the existence of trees because of their role in sustaining the Earth’s biosphere, which is the summum bonum on God’s good Earth. But willing something in a secondary sense, purely for the sake of some “greater good,” cannot be called love, in the true sense of the word. Only when a thing is willed for its own sake, as an end-in-itself, can we properly say that is is loved. Does God love trees, then? We don’t know. Perhaps He is an artist Who enjoys their beauty for its own sake; or perhaps He is a utilitarian Who creates and ruthlessly destroys species, depending on whether they subserve the flourishing of the biosphere. In that case, we could say that He loves Gaia, but not trees. And what, one wonders, would he think of a species such as Homo sapiens, which has destroyed thousands of other species and which (according to many scientists) poses a clear and present danger to the Earth’s biosphere? Would He love a species like that? Hmmm.

I respectfully submit that if God did not decree my coming into existence, then even on a Thomistic analysis, it would be meaningless to say that He loves me. And if He is not committed to my continuation in existence, then it makes no sense to say that He loves me, either; at most, one might say that He loved me (or that He timelessly loves me up until the year 2018). Furthermore, unless God wills that I should exist for my own sake, and not merely for the sake of some “greater good,” it would be improper to say that He loves me. Feser’s argument fails to establish any of these things; thus it falls a long way short of establishing God’s love for us, in any minimally meaningful sense of the word.

Suggested solutions to the above difficulties

Is there anything Feser can do to remedy these defects in his argument? There is. First, he could point out that the dichotomy I have posed above (either God loves creatures as ultimate ends or merely as means to a greater good) is a false one: there is nothing to prevent God loving creatures both as means and as ends. St. Thomas Aquinas, for instance, saw no contradiction in saying that creatures have their own proper ends, while also serving the needs of other creatures, and additionally contributing to the perfection of the universe as a whole:

…[A]ll parts of the universe are ordered to the perfection of the whole. For all parts are ordered to the perfection of the whole, inasmuch as one is made to serve another. Thus, in the human body it is apparent that the lungs contribute to the perfection of the body by rendering service to the heart; hence, it is not contradictory for the lungs to be for the sake of the heart, and also for the sake of the whole organism. Likewise, it is not contradictory for some natures to be for the sake of the intellectual ones, and also for the sake of the perfection of the universe (Summa Contra Gentiles Book III, chapter 112, paragraph 8).

Second, with respect to the question of creatures’ continuation in existence, the vast antiquity of the cosmos gives us some assurance that God will not end it tomorrow: at least, we have no reason to think He will. And while species come and go, over the course of time, the average duration of a species is hardly short: roughly, a few million years, depending on what group of animals it belongs to. It should be added that when species do go extinct, it is generally in response to environmental changes, and they are usually rapidly replaced by other species which fill their ecological niches.

On an individual level, it is indeed difficult to mount a case that God loves this or that creature. What about human beings? The one big thing that human beings have going for them is that they, unlike other animals, are capable of knowing and loving their Creator. This suggests that human good cannot be subsumed under the notion of what is good for Gaia: indeed, we can even dream of moving to another planet (not a very wise thing to do, however). Insofar as we can contemplate the things of eternity, we transcend the good of the biosphere. What’s more, humans are also moral agents, and each of us is morally and spiritually unique. One can therefore at least entertain the possibility that each of us may be destined for a relationship with our Creator which goes beyond the grave, in some dimension of existence we cannot presently fathom. I shall conclude my review with a quote from Thomas Paine’s Age of Reason:

I trouble not myself about the manner of future existence. I content myself with believing, even to positive conviction, that the Power that gave me existence is able to continue it, in any form and manner he pleases, either with or without this body; and it appears more probable to me that I shall continue to exist hereafter, than

that I should have had existence, as I now have, before that existence began. (End of Part I)

Well, I guess that’s enough for one day. What do readers think? Over to you.

Vincent,

As if fungal infections, wood-boring beetles, and lumberjacks weren’t also sources of harm to trees.

Feser’s got a lot of ‘splainin’ to do if he wants to get God off the hook for harming his creatures. (And so does any theist who believes in a powerful and benevolent God, of course.)

So many words, so little evidence. None of the latter, that I can see.

I don’t necessarily mind per se, but who here is even interested? The non-believers don’t see the first bit of evidence to incline them to start down this road of speculation, and it seems not to engage the believers either.

Really, I have some acquaintance with scholastic thought, but learned about it mainly because it never got beyond speculation. Science did, by using evidence. We need evidence to begin to care about any of this.

Glen Davidson

Vincent,

I’m not known for defending God as loving, by any stretch. The evidence suggests that if he exists, which is doubtful, he’s either weak or not particularly loving.

Still, I think you go to far in inferring that unless God specifically decreed your existence, he doesn’t love you. Humans love their children despite not having decreed their existence. What prevents God from doing the same?

quote:

The problem with this view, as Kenneth Pearce points out in his article, Omnipotence in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, is that creating a stone which its creator cannot lift is a logically possible action: I’m quite capable of making a stone which I can’t lift, for instance.

end quote:

Just an aside

making is not the same thing as creating. Making involves using preexisting materials while creating does not.

I’m reasonably sure humans can’t create anything in the physical realm we can only create in the mental realm and then represent what we have created in the physical

peace

question:

Did I miss where Feser established that God is personal?

peace

quote:

The section on God’s love in Feser’s book is surprisingly short: less than a page.

end quote:

Here is a good reason to begin with God’s own self-revelation.

Does anyone think that if you began with Christ you would have less than a page devoted to God’s love?

peace

That objection misses the point, I think–but not because of of what “creation” means. The problem is a result of what “omnipotence” means.

Hi keiths,

Nothing prevents Him from doing so, but the question I’m asking is: what reason is there to think that He does so? Recall that according to Feser’s Thomistic argument, God wills the existence of things, which means that He wills whatever goods are required in order for those things to exist; but since to will what is good for a thing is simply to love that thing, it follows that God loves those things. But if God did not will my existence, then the above argument would supply no reason to believe that He wills what is good for me, and hence no reason to believe that He loves me. He may of course do so, but it would need to be argued for.

Hi fifthmonarchyman,

It’s very brief, but it’s there. On pages 190-191, Feser rails against the “theistic personalism” espoused by philosophers such as Alvin Plantinga, who treats God as falling under the genus person, and then he adds in brackets:

So there you have it. On Feser’s account, God is personal because He possesses intellect and will. This is a fairly standard argument for classical theists.

Good point. Cheers.

All this doing stuff implies that god experiences time. I find that risible and incoherent.

petrushka,

It’s logically possible for a timeless God to interact with a temporal world. It’s just that all the interactions happen within the same timeless “instant”, from his perspective.

By analogy, imagine that you are a God presiding over a world that consists of a line segment. The beings in this world are confined to the line segment and can only experience (and interact with) the part of the segment where they are currently located.

You, by contrast, are off the line. You can interact with different parts of the line simultaneously. It’s all present to you, because you are not trapped on the line as the beings in your world are.

keiths:

vjtorley:

Your statement was much stronger than that:

Whether he decreed your existence is orthogonal to the question of whether he loves you. As you point out in the OP, it’s possible that he “decreed your existence” as a mere means to an end, in which case he might not love you at all. On the other hand, it’s possible for him to love an “undecreed” child the same way its human parents might.

Would God “always” know that it would love all those things that it “comes to love”?

If God were all-knowing, that would mean He would have known that Adam and Eve would sin, which makes the whole idea of the test with the tree of knowledge of good and evil pointless…

J-Mac,

It’s pretty clear that the author(s) of Genesis did not see God as omniscient. Far from it. He comes across as quite the doofus.

I don’t think it was a test for God to see what Adam and Eve would do as much as a demonstration for posterity to see what Adam and Eve would do.

peace

fifth:

It wasn’t merely a demonstration for posterity. It’s the whole basis for the Fall, after all!

O felix culpa and all that.

Interesting,

It looks to me to be more of a definition than an argument

Does Feser think that God is a person because he possesses intellect and will or does he think he possesses intellect and will because he is a person?

I would not think calling God personal would entail that he falls under the genus “things that are personal” anymore than calling him loving entails that he falls under the genus “things that are loving”.

Certainly God’s personalness like his lovingness would be unique to him and only shared by other beings in a analogical way.

peace

But if God is all-knowing, then he had already known what they would do…

If that’s the case it makes God responsible for all the evil that the test led to… This makes God’s omnipotence a bit sketchy for not being able to prevent the evils that it led to…

Why setup a test you already know the devastating results of?,

Something’s fishy about that…

In one sense God is responsible. If there was no world to begin with there would be no evil in the world. Even you would agree with that wouldn’t you?

On the other hand Adam is responsible for the consequences of his own choice. Adam ate the fruit willingly God did not compel him to do so.

Perhaps to contrast Adam’s unfaithfulness with the faithfulness of Christ

peace

God could have prevented the evils that came from the fall by never creating man in the first place.

I know I’m glad he did not choose to do that.

peace

Yeah… but why bother then with all this creation, if you already know the devastating outcome?

It makes no sense and suggests failure on God’s part that even you wouldn’t agree with, would you?

fifth:

He could also have prevented them by a) creating a better kind of man, one who would be able to resist the temptation, or b) removing the temptation that he already knew was going to cause problems. Either way he could have prevented the Fall.

Not particularly bright, is he?

The outcome includes me and every one I know and love including Jesus so I would not call it devastating.

I don’t think it suggests a failure I think it suggests that God had a good reason for allowing the fall.

peace

Yeah… but why not spare all the suffering by using omniscience and omnipotence and create new Adam and Eve leading to you and me without aches and pains plus Jesus? Wouldn’t that be loving?

You mean that reason was that he had already known the outcome?

A new Adam and Eve would not lead to you and me. They would lead to some other people or no people at all.

Haven’t you heard of the grandfather paradox? change one small thing about the past and the present changes radically. Multiply that by 9 billion.

And Jesus would not have had to come if there were no sinners to save.

peace

No, I don’t know God’s reason for allowing the fall for certain.

I speculate that he allowed Adam to sin because giving Grace to sinners like me is better than not allowing us to exist in the first place.

whatever the reason it was good enough for God to consider creating the world worthwhile even though he knew what the outcome would be.

peace

Here is an interesting speculation as to why God might have allowed the fall. Maybe he did it to maximize the number of humans.

From here

http://triablogue.blogspot.com/2018/02/hilberts-hotel.html

peace

fifth,

That’s a silly argument.

An omnipotent God would have to be very stupid not to come up with a better way, than the Fall, of maximizing the number of heaven-bound humans.

On the other hand, such a stupid scheme does fit well with the God of the Bible, who is not the sharpest (or kindest) tool in the theistic shed, after all.