Christian apologist Professor Tim McGrew recently defended the historicity of Matthew’s account of the guard at the tomb, in a post put up by his wife, Dr. Lydia McGrew. Professor McGrew’s post was written in response to a challenge he issued to me, in response to my (generally positive) review of Michael Alter’s book, The Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry (2015), which was published at The Skeptical Zone last year. Not wishing to address the bulk of Alter’s arguments, which he considered unconvincing, Professor McGrew challenged me to narrow the focus of our discussion, by listing three of Alter’s arguments which I had found particularly convincing. The first topic on my list which Professor McGrew chose to address was the question: was there a guard at Jesus’ tomb? However, it turns out that McGrew’s argument for the historicity of Matthew’s story of the guard is based on faulty math – a surprising flaw, coming from a man who has written extensively on the subject of Bayes’ Theorem and its role in Christian apologetics. Before we have a look at the math, though, I have a special announcement: Michael Alter himself has decided to weigh in on the controversy, and I have included his remarks in this post.

Curious, that!

Before I continue, let me begin by pointing out four curious facts, which may be of interest to readers.

First, I actually wrote a comment in reply to Professor McGrew’s post, which was never published. Funny, that. Now, I don’t wish to complain about this – after all, the people in charge of What’s Wrong With the World (the blog on which Professor McGrew’s post can be found) have every right to make their own rules, as it is their blog. However, I will note for the record that since the tone of my reply was entirely civil and (I believe) in keeping with the blog’s stated posting rules, I had a reasonable expectation that it would be published.

Second, in his post, Professor McGrew only quoted the first half of my argument, omitting the second half, which I consider to be by far the stronger half. Let me be clear that I am not accusing Professor McGrew of making a deliberate omission, as he subsequently attempted to rectify his omission with a comment attempting to address the second half of my argument. Nevertheless, the original omission betokens a certain carelessness on Professor McGrew’s part: a dangerous failing, when one is engaging in controversy.

Third, the list of three “test cases” displayed in Professor McGrew’s post which we agreed to debate is not the same as the list which I originally provided him. Here is his list of the three topics to be covered:

Since I am unimpressed by Alter’s arguments, I asked Torley to pick three particular arguments as test cases… Torley chose the three following points for this test:

1. Was there a guard at Jesus’ tomb?

2. Did Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple stand at the foot of the cross?

3. Was Jesus buried in a new rock tomb? (specifically, a tomb owned by Joseph of Arimathea)

However, in actual fact, I offered Professor McGrew a choice of two topics for the first test case: (i) Were Jewish saints raised at Jesus’ death? or (ii) Was there a Guard at Jesus’ tomb?

Professor McGrew then chose the former option, in an early response to my review of Michael Alter’s book. I am therefore a little puzzled as to why he has suddenly changed course, and chosen the latter option instead. Now, Professor McGrew has a perfect right to change his mind, and I presume he has done so for tactical reasons. That is his privilege. Nevertheless, a public acknowledgment of this change of tack would have been courteous to his readers.

Finally, Professor McGrew made no attempt to notify either me or Michael Alter about the post which he had authored. I stumbled on it by accident a short time after he had written it, as I occasionally peruse the What’s Wrong With the World blog for its articles of topical interest. Michael Alter heard about the post from Professor Joshua Swamidass, who thought he might wish to respond – which he did. I hereby invite readers to carefully examine Michael Alter’s response, which I have included in this post. Here it is, in full. Below Michael Alter’s response, I have written my own detailed, mathematical response to Professor McGrew’s defense of the historicity of Matthew’s story of the guard.

=======================================================

CORRECTED and UPDATED RESPONSE TO TIM MCGREW’S “Was there a guard at Jesus’ tomb?” by Michael Alter

Recently, Dr. S. Joshua Swamidass kindly sent me an e-mail providing information that Dr. Tim McGrew had published a guest post response to Vincent Torley’s review of my text, The Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry (2015) in his wife’s group blog: What’s Wrong With the World. First, I am honored that a respected, knowledgeable, and published authority has taken time out of his busy schedule to respond to Vincent Torley’s review of my text. His time is respected.

Now then, let me respond to several points addressed by Tim:

- Tim wrote: Since I am unimpressed by Alter’s arguments…

RESPONSE: Tim is unimpressed of Vincent’s review / summary of my text. His opinion is absolutely respected. However, it is significant that presumably, Tim has not examined my text. At least this is my gut feeling after having read his introduction. In my opinion, if Tim has read my text, he should have made this point clear to his readership. If I am in error, please correct me and excuse me. Therefore, it must be repeated for emphasis that he is only responding to Vincent’s review of my text. Perhaps, it might be harsh, but imagine a movie critic critiqued a movie without seeing it. Or, imagine that a music critic published a review of the Cleveland Orchestra’s performance of Beethoven’s 9th symphony without having heard and seen the actual performance. Finally, imagine that a chess expert analyzed a chess match without having witnessed or seen the chess notations of that match. In the three examples just identified, the evaluation was merely based on an earlier reviewer’s published review. Question: Do you think that the evaluation is fair?

2. It [the guard at the tomb] is mentioned only in Matthew’s Gospel, not in the other three… the argument from silence in such cases is generally terribly weak… As Torley has not attempted to argue that the silence of the other evangelists meets the probabilistic challenge laid out there, I will not belabor the point.

RESPONSE: To the contrary, numerous bible commentators (on both sides of the religious aisle) doubt or question the historicity of Matthew’s account of the guard at the tomb (Dale Allison, C H Dodd, Raymond Brown, R H Gundry, The New Catholic Encyclopedia, etc. On pages 297-299, I offer several “SPECULATIONS” for Matthew’s rationale for inventing the Guard Episode. Although various explanations are possible, I elected to focus on, and explore the rationale discussed by Elaine Pagels. Unfortunately, in my opinion, you did not evaluate her writing.

Most significant, the historicity / veracity of the tomb itself is a point of contention and discussion. On pages 337-339, I identified at least fifteen scholars, theologians, and historians. Numerous times, I include their commentary. Yet, you chose not to belabor the point. Your decision is respected, however, it is NOT fair to my text.

3. Torley objects that the account does not explain why the body could not have been stolen on Friday night.

RESPONSE: On pages 340-343, I specifically presented William Lane Craig’s discussion on this specific topic. After presenting his apologetic, I offer my rebuttal. Your essay responds to Vincent’s rationale, it does NOT respond to my rationale. Once again, this is not fair, and disingenuous to your readers.

4. You wrote: “The third objection is that Matthew’s narrative does not tell us why Pilate would acquiesce in the request of the Jewish leaders.”

RESPONSE: Pilate’s rationale is subject only to scholarly speculation. And yes, you offer several thoughtful ideas on this topic. Thank you! But, these too, are just scholarly speculations. However, here too, these speculations are depended upon the historicity / veracity of a tomb burial. Furthermore, there is scholarly speculation as to the meaning of Pilate’s words: “Take a guard,” or “You have a guard.” That topic, too, is discussed on page 294.

5. You wrote: The fourth objection is that the Jewish leaders would not have asked Pilate to set a guard at the tomb, since it was the Sabbath day, and Jewish law would have forbidden them to hire a gentile to do such work on the Sabbath.

RESPONSE: You added: “First, even supposing the objection to be fairly stated, there is no guarantee that the Jewish authorities would be particularly scrupulous in the matter of hiring a Roman guard to do their work, as they had already shown their willingness to hold a trial by night in prima facie violation of their own rules.” To be one hundred percent honest, this statement makes me cringe. Is it possible that this invented episode (and the trials) is/are, in fact, an argumentum ad hominem against the Jewish leadership (Jewish people)? If you excuse me, you continue the myth of the degradation of the Jewish leadership. I will be the first to admit that not everyone is “wonderful”… And, the Tenakh is clear that numerous times the Jewish people have fallen short of the mark / not been Torah faithful. However, numerous commentators, on both sides of the religious aisle frankly discuss plentiful examples of anti-Semitism recorded in Matthew, and elsewhere in the Christian Bible. Unfortunately, since you presumably (again, I could be in error) have not read my text, you did not comment on pages 343-344. Not to hit a dead horse, but this failure on your part is not fair and it is disingenuous to your readers.

In closing you write: “I conclude that on the first point, Alter’s argument, as summarized by Torley”… This reminds me of a famous quote by the Jewish poet Haim Nachman Bialik. Hopefully, the analogy will be self-evident. “ Reading the Bible in translation is like kissing your new bride through a veil.” Those who understand, will understand…

Take care.

Mike

===========================================================

I’d like to thank Michael Alter for his well-written response to Professor McGrew. I’d now like to address the substance of Professor McGrew’s argument for the historicity of Matthew’s story of the guard at Jesus’ tomb.

A preliminary observation

First of all, I’d like to draw Professor McGrew’s attention to a remark I made, in the same comment where I posed my challenge to him:

In what follows, the question I’d like to address is not whether these claims are true, but whether or not they are probable, when judged on purely historical grounds, by a fair-minded historian with no anti-supernaturalistic bias. [The emphases have been added by me – VJT.]

In his post, Professor McGrew concludes that “Alter’s argument, as summarized by Torley, completely fails to undermine the credibility [of] Matthew’s account of the setting of a guard at the tomb where Jesus had just been buried.” But all that goes to show is that Matthew’s story of the guard is possible, not that it is historically probable. More is needed.

I should also note that Professor McGrew’s post contains no less than four instances of “might have” or “might still have.” Once again, this is not the sort of language one employs when attempting to build a probabilistic case.

So where’s the beef?

Surprisingly, the real substance of Professor McGrew’s argument for the historicity of Matthew’s story of the guard at Jesus’ tomb is not contained within his post, but in a comment he wrote four days later, in response to a critic. Here’s the relevant excerpt:

It is a matter of balancing probabilities and inclining to the most likely. There are three independent variables here: the prior probability that a guard was set, P(G), the probability of our having the Matthean account, given that a guard was set, P(M|G), and the probability of our having that account, given that a guard was not set, P(M|~G). I contend that, on the basis of such information as we actually possess, P(G) is not particularly low, and therefore the ratio P(G)/P(~G) is not significantly less than 1. I have disposed of Alter’s attempt to argue to the contrary. P(M|G) is not itself wildly low; if that is what happened, this is more or less the sort of account we might hope to have of it. P(M|~G), however, is very low; I cannot see why anyone would think it is even on the same order of magnitude as P(M|G). Therefore, P(G)/P(~G) ≈ 1, and P(M|G)/P(M|~G) >> 1; therefore, P(G|M)/P(~G|M) >> 1; therefore, P(G|M) is easily more likely than not.That’s all.

Professor McGrew’s mathematical reasoning is sound, given his three premises, which are that:

(i) the prior probability P(G) of a guard being set over Jesus’ tomb is not particularly low;

(ii) the probability P(M|G) of our having Matthew’s account, given that a guard was set, is not wildly low – indeed, M is something we might expect, given G;

(iii) the probability P(M|~G) of our having Matthew’s account, given that a guard was not set, is very low – in fact, orders of magnitude lower than P(M|G).

In a nutshell: the premises which I contest are premises (ii) and (iii). I think P(M|G) is very low, while P(M|~G) is low, but nonetheless greater than P(M|G) – even on the assumption of an empty tomb.

Why Matthew’s story actually makes more sense if there were no guard

Let’s address Professor McGrew’s premises in reverse order, and start with premise (iii). Why do I contest McGrew’s claim that P(M|G) is massively greater than P(M|~G), while conceding that P(M|~G) is low? Briefly, there are two probabilities we need to consider when looking at the story of the guard in Matthew’s gospel: the probability of such a story being created in the first place, and the probability of its being circulated. The latter is of vital importance, because even a true story will never end up in anyone’s gospel, unless it circulates well enough to reach the ears of the gospel’s author. Now, if there actually were a guard at Jesus’ tomb, then the creation of the story poses no problem: Matthew is simply narrating what actually happened. However, the circulation of a story like the one we find in Matthew’s gospel is extremely unlikely, since it would have been counter-productive for the guards to spread it, as they would have been putting their lives in danger by doing so, for reasons we’ll discuss below. And even if we throw in the additional fact of the empty tomb, and grant that the tomb of Jesus was mysteriously opened while the guards were on duty, one would still not expect them to circulate the story which Matthew claims they did: “His disciples stole the body while we were all asleep.” To quote Alter, “it would have made much more sense for the Sanhedrin to have told the soldiers to say nothing at all or to report that everything was in order and that they had left at the proper time (Schleiermacher 1975, 430).”

On the other hand, if there were no guard at Jesus’ tomb, then there would have been no obvious motive to invent the story of the guard, in the first place. In his book, Alter suggests possible motives, but they are simply that: possibilities. (Incidentally, while we’re on the subject of possibilities, I should mention another interesting hypothesis for the origin of the guard story in Matthew, suggested by Alter in his book (2015, p. 342): “Matthew creatively and skillfully weaves a legendary account incorporating passages from Joshua 10 and Daniel 6 that are supposedly fulfilled by Jesus.” Make of it what you will. All I will say is that the account in Joshua 10:16-27 resembles Matthew’s account in several respects: it features a cave whose mouth is covered up with large rocks, with bodies inside [live ones, in the book of Joshua], and several guards posted outside.) However, once the story of a guard at Jesus’ tomb had been invented (for whatever reason), there would have been no powerful reason not to allow it to circulate freely, as it would have jeopardized no-one, meaning that no-one had any motive to suppress it.

In short: the main hurdle for P(M|~G) to overcome is its creation: why invent such a story in the first place? Once created, however, it could freely circulate. P(M|G), on the other hand, faces no creation hurdle, but a massive circulation hurdle, for two reasons: (a) circulating the story posed a real danger to the guards, who were allegedly the first people to propagate it, since (as we’ll see below) spreading the story put their lives at risk, and (b) the guards would have been better served by spreading another story, instead: “Nothing happened.” Had this lie been too difficult to sustain in the face of contrary evidence, then how about this one: “The earthquake [which Matthew 28:2 tells us was a violent one] broke the seal of the tomb and also caused the body of Jesus to disappear down a crevice.” And even supposing there had been a public clamor for Jesus’ dead body, in order to quell the rumors of its having been resurrected, the guards could have stolen the body of another executed criminal from somewhere (say, a burial pit), and placed it in Jesus’ tomb. Would this have been difficult to carry out? Not at all. We need to bear in mind that according to Jewish religious law, corpses were deemed to be no longer legally identifiable with any certainty if they were more than three days old (see here). The apostles didn’t start publicly preaching Jesus’ Resurrection until seven weeks after the Crucifixion – which means the guards would have had plenty of time to organize their fraudulent scheme, before word of Jesus’ Resurrection got around. There are lots of other stories, then, which the guards could have told, to spare themselves public embarrassment and punishment at the hands of Pilate.

To sum up: the flaw in Professor McGrew’s claim that P(M|G) is massively greater than P(M|~G) stems from the fact that he considers only the probability of the account we find in Matthew’s gospel being created in the first place, while ignoring the much greater problem of its being circulated, initially by the guards themselves, and subsequently, throughout the wider community, over a period of decades.

Is Matthew’s account what we would expect, if there were a guard at Jesus’ tomb?

I’d now like to explain why I contest premise (ii) of Professor McGrew’s argument, that

the probability P(M|G) of our having Matthew’s account, given that a guard was set, is not wildly low: indeed, McGrew thinks P(M|G) might appear reasonably high, if we only had the first part of Matthew’s guard story in front of us (Matthew 27: 62-66), in which the chief priests ask Pilate to give the order for Jesus’ tomb to be made secure. If there actually were a guard, then that’s the kind of historical record we might expect. But there’s more to the story than that. An angel comes down from heaven, rolling away the stone and causing the guards to faint; the guards subsequently report what has happened to the chief priests, who bribe them to spread the story that they fell asleep, and that the disciples stole the body while they were asleep. Once we include this part of Matthew’s guard story, P(M|G) drops dramatically, as it rests on a massive psychological implausibility, which has nothing to do with miracles. Put simply: nobody in first-century Palestine would believe the story peddled by the chief priests, that all of the guards fell asleep at the same time, and none of them woke up while the disciples broke the seal of the tomb, rolled back the stone, and removed the body of Jesus, despite the fact that the penalty for guards falling asleep was crucifixion upside down! That story just wouldn’t wash. Even if there were a guard at Jesus’ tomb, one would not expect an account of the guards behaving in such a silly fashion: first, accepting a bribe, and then spreading a story which would put them all in mortal danger.

At this point, P(M|G) appears to be very low indeed. Let’s have a look at the apologetic attempts to reinflate it.

At the very end of Matthew’s account of the guard, the chief priests try to allay the guards’ fears of being executed on a charge of falling asleep at their posts, by promising to persuade Pilate not to punish them. One commenter on Professor McGrew’s post proposed that the chief priests thought they could convince Pilate to (at least publicly) go along with the false story that they were peddling for public consumption, even though he would have known perfectly well that it was false. This commenter was fair enough to acknowledge the inherent unlikelihood of Pilate listening to the Jewish leaders’ advice and agreeing to “hush up” the issue and let the soldiers live, but then argued that he would have reluctantly agreed to do so, in order to avoid an even greater evil: public insurrection. On the scenario proposed by the commenter, the Jewish leaders may have said to Pilate: “A story that Christ’s followers stole his body will help quell his faction, and a story that some supernatural power overwhelmed the soldiers will foment unrest, so it is in your interest as well as ours to back the version we put out.” Professor McGrew then contributed a clarifying remark of his own, in response to the commenter’s suggestion (emphases mine – VJT):

We are not told whether the move to shield the soldiers worked; we are told only that this is how they were induced to acquiesce in the tale.Many real events seem far less probable on their face than this. The career of Julius Caesar is an instance — or far more incredibly, that of Napoleon Bonaparte. If we were allowed to use uncalibrated personal incredulity as a principle of inference, it would send a wrecking ball through the discipline of history, ancient and modern. Donald Trump, anyone?

So where are we now? Has Professor McGrew succeeded in restoring P(M|G) to the level of reasonable probability? Not at all: the examples he cites merely demonstrate that highly improbable events sometimes happen – like a dead whale ending up in a mangrove forest. But that does not render these events any less improbable.

Professor McGrew also objects that arguments from personal incredulity would undermine the study of history. But the difference here is that Matthew’s account of Jesus’ Passion and Resurrection is not just any old historical account: it is avowedly biased (being written from a Christian perspective), heavily supernatural in its subject matter, and contains what appear to be numerous dramatic embellishments which the other Gospel accounts lack – such as Jewish saints coming to life at Jesus’ death and subsequently appearing to people, or an angel rolling back the stone. I put it to my readers that a responsible historian would be grossly remiss in accepting these accounts at face value. They deserve to be subjected to a more skeptical kind of scrutiny than most other historical accounts. Allow me to quote from the words of a real historian: Dr. David Miano, Lecturer in History at UC San Diego. In his blog article, How Historians Determine the Historicity of People and Events (June 10, 2018), he writes:

Some general rules of thumb that can be used in evaluating a source would be: (1) the closer in time and place that the source is to the historical event, the better. This makes sense, because the longer the gap in time between the event and the writing, the more time there is for the story to be embellished, confused, doctored, misunderstood, or exaggerated. This is not a hard-and-fast rule, because it is possible for a later source to be more reliable than an earlier source, but generally speaking, time allows a story to pass out of memory and to be transformed into legend. (2) separate the core testimony from the biased presentation. Oftentimes the wording that a writer may use to tell a story employs loaded language designed to sway the reader in a certain direction. A historian is wise to wade through the rhetoric to get to the basic witness of the document.When we examine the testimony given in any written source, we first try to ascertain plausibility, and then probability. A claim that is plausible might not be probable, after all.

“A claim that is plausible might not be probable, after all.” Words well worth remembering. And let us add: the scenario we are considering here isn’t even a plausible one: the most one could say is that it’s possible, despite its massive implausibility.

Is there any other plausible way of boosting the probability P(M|G)? The commenter whom I quoted above nominates the publicly known fact of the empty tomb: in his opinion, “the probability that given an empty tomb fact, they [the chief priests] could convince Pilate to allow the theft account to go out for public consumption… is indeed quite reasonable.” But as I’ve argued above, even if the fact of the empty tomb became publicly known, the earthquake would have served as a convenient excuse for the body’s absence. Additionally, it would not have been difficult for the guards to substitute the body of an executed criminal for the missing body of Jesus, had they wished to: they had seven weeks to do it.

One last possible way of boosting P(M|G) is by supposing additionally that Jesus actually rose from the dead, and that an angel rolled back the stone. The flaw in this assumption should be readily apparent to everyone: it assumes the very thing which it sets out to prove: the Resurrection. I am forced to conclude, then, that the attempts to render P(M|G) reasonably probable are all failures.

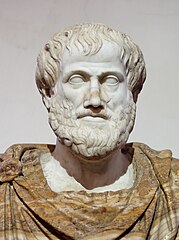

Too incredible to invent: Professor McGrew appeals to Aristotle

In a comment attached to his post, Professor McGrew also chides me for expressing incredulity at an attempt by a Christian apologist (Wenham) who argues from the improbabilities in the story (conceived as a story) that the best explanation for why it is told is that it was notoriously true. As I put it in my review: “Wenham is inclined to credit the story of the guard, precisely because it’s so full of obvious holes that he thinks no-one would have made it up in the first place.” McGrew contends, quoting Aristotle, that I am being grossly unfair to Wenham. But even if I am, that, in and of itself, does nothing to establish that the story of the guard is probably true – a story which Wenham himself concedes “bristles with improbabilities.” Surely a fair-minded historian would take note of these improbabilities, and evaluate accordingly. Once again, I ask: are we to believe Matthew’s claim that the chief priests and the guards (Mt. 28:12-13) deliberately circulated the story that all of the guards fell asleep, which would leave them liable to a capital charge? Is that historically probable?

But let us examine Aristotle’s argument. Does he say what Professor McGrew claims he says in his Rhetoric 2.23.21 (1400a)? Aristotle writes: “For the things which men believe are either facts or probabilities: if, therefore, a thing that is believed is improbable and even incredible, it must be true, since it is certainly not believed because it is at all probable or credible.” This argument deployed here is very similar to Tertullian’s “certum est, quia impossibile” (which is often misquoted by skeptics as credo quia impossibile).

Professor McGrew seems to be interpreting Aristotle as arguing that a claim is more credibly true if it is prima facie incredible, on the grounds that its very incredibility militates against its having been made up: no-one would be dumb enough to make up a story full of holes. With the greatest respect, I don’t think that’s what Aristotle is arguing in the passage quoted above. Instead, I think that the point he is making is that a claim is more credibly true if it is widely accepted (“believed”), despite its prima facie incredibility, as such an incredible-sounding claim is unlikely to be widely believed by men unless it has strong independent support, which nobody can gainsay. As I read him, Aristotle is putting forward something like Nachmanides’ kuzari argument, which features heavily in Jewish apologetics.

Assuming my interpretation is correct, the question we need to answer is: was the story of the guard at the tomb ever widely believed by the Jews? Aside from Matthew’s Gospel, we have absolutely no grounds for thinking that it was. All we know, from later Jewish polemics against Jesus, is that the Jews believed the disciples had stolen his body. For instance, Justin Martyr, in chapter 108 of his Dialogue with Trypho, mentions the Jewish claim that Jesus’ disciples “stole him by night from the tomb, where he was laid when unfastened from the cross, and now deceive men by asserting that he has risen from the dead and ascended to heaven.” But that polemic proves absolutely nothing about the existence of a guard.

So it seems that Aristotle’s weighty authority does not support Wenham’s argument, after all.

Where Professor McGrew and I more or less agree

Professor McGrew will be delighted to learn that I am prepared to concede the first premise of his argument. (I would be happy to set P(G) at 0.1, or 10%, for the sake of argument. Certainly I would put it at more than 1%, after carefully weighing the arguments which Professor McGrew marshals in his post.) Premise (i) is of course predicated on the assumption that Jesus was actually buried in a tomb. I had previously maintained that an independent historian would conclude Jesus’ body was most likely thrown in a common burial pit for criminals, having been influenced by Professor Bart Ehrman’s spirited defense of this view. Since writing my review of Michael Alter’s book, I have examined the literature on the subject more carefully, and I now think the matter is far from settled. Jesus’ burial in a tomb remains a strong possibility, although I continue to vigorously maintain that it was not a new tomb owned by Joseph of Arimathea, as three of the Gospels claim. (Mark’s Gospel doesn’t say if it was new or not.) I would also maintain that John’s account of Jesus’ burial by Joseph of Arimathea (and Nicodemus) is heavily embellished. However, I am now prepared to grant that the prior probability of a guard being posted at Jesus’ tomb, as Matthew narrates, is not as low as I had previously thought.

What prompted my change of mind? Let’s examine some of the key arguments I brought forward in my review of Alter’s book. Professor McGrew has helpfully summarized these arguments under four points, which I have listed below (with very slight modifications in the interests of clarity), along with his responses and my counter-responses. (Of these four points, C and D relate directly to the prior probability of a guard being set over Jesus’ tomb – in other words, P(G).)

A. The guard at the tomb is mentioned only in Matthew’s Gospel, not in the other three. [McGrew’s response: “the argument from silence in such cases is generally terribly weak.”] [My reply: fair point.]

B. Matthew’s account fails to explain why the body could not have been stolen on Friday night. [McGrew’s first response: some scholars have argued that when properly interpreted, Matthew’s account actually implies that the chief priests could have made their request for a guard on Friday evening, which means that if Pilate promptly granted the request, Jesus’ body could not have been stolen on Friday night, after all.] [My reply: the scholars McGrew cites (Doddridge, Paulus, Kuinoel, Thorburn) all wrote in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Is this the best he can do? In his book, Alter mentions another source dating from 1893, making the same claim, but goes on to note: “Most commentators presume that the visit was held on Saturday morning” (2015, p. 288).] [McGrew’s second response: even if the Jewish leaders had to wait until Saturday to obtain a guard from Pilate, they “might have left someone of their own to keep an eye on the tomb overnight. Failing that, they might still have thought that it would be better than nothing to have a guard set for the remainder of the time period specified” (italics mine – VJT.)] [My reply: McGrew is clearly reaching here. “Might have” establishes mere possibility, not probability.]

C. We are not told why Pilate would agree to the Jewish leaders’ request for a guard over Jesus’ tomb. In particular:

1. The request concerned a purely religious matter, and we would not expect Pilate to care much about such things. [McGrew’s response: “An imposture {on the part of Jesus’ disciples} might well raise civil trouble in Jerusalem… Preventing civil unrest lay squarely within Pilate’s sphere of responsibility. On this count, the matter is exactly the sort of thing we would expect the Jewish rulers to request of Pilate.”] [My reply: if we assume for the sake of argument that the Jewish leaders were actually aware of a rumor that Jesus had claimed he would return to life after his death, then McGrew has a valid point here. However, the assumption McGrew is making here does not enjoy a scholarly consensus: it is possible, but has not been shown to be probable.]

2. Pilate had just been pressured into ordering Jesus’ crucifixion, and therefore any further request would be unlikely to meet with a favorable reception. [McGrew’s response: “The theft of a body and proclamation that the individual in question was alive was the sort of scenario a Roman governor under Tiberius could not safely ignore.”] [My reply: the example McGrew cites to support his case relates to a conspiracy which the Roman Emperor Tiberius feared, against his own life. Jesus posed no such threat, although McGrew could perhaps urge in reply that Jesus was crucified as the “King of the Jews,” making him a pretender in the eyes of Rome, and hence someone whose resurrection would be bad news for Pilate.]

D. The Jewish rulers would not have made such a request of Pilate, since a gentile employed by a Jew would not be allowed to work on the Sabbath. [McGrew’s response: “there is no guarantee that the Jewish authorities would be particularly scrupulous in the matter of hiring a Roman guard to do their work, as they had already shown their willingness to hold a trial by night in prima facie violation of their own rules.” In any case, nothing in Jewish law prevented them from “making a request to Pilate, as the civil governor, that he would secure the tomb with a guard.”] [My reply: the first part of the response naively assumes that the negative portrait of the Jewish authorities in Matthew’s gospel is historically accurate. The second part of the response is more substantial, and makes a valid point.]

When all is said and done, I’m prepared to concede that McGrew’s responses to my foregoing arguments at least show that the prior probability P(G) of a guard being set over Jesus’ tomb is not as low as I had imagined. However, nothing in his responses suggests that this prior probability would be especially high, either. For argument’s sake, I’m prepared to accept that P(G) = 0.1.

Summing up

As we saw above, Professor McGrew’s reasoning was as follows:

“P(G)/P(~G) ≈ 1, and P(M|G)/P(M|~G) >> 1; therefore, P(G|M)/P(~G|M) >> 1; therefore, P(G|M) is easily more likely than not.” I, on the other hand, would argue that

P(G)/P(~G) ≈ 0.1, and P(M|G)/P(M|~G) is considerably less than 1; therefore, P(G|M) is quite unlikely, after all. I leave it to readers to decide who has the better of the argument.

I would like to conclude by thanking Professor McGrew for this exchange of opinions. He is welcome to comment on this post. What do readers think? Over to you.

APPENDIX

The following is an excerpt from Michael Alter’s book, The Resurrection (2015, pp. 340-342), in which Alter proposes a scenario as to how Matthew’s story of the guard might have originated. After presenting this scenario, I’ll briefly examine Professor McGrew’s criticisms of it. I hope this information will help readers form a better evaluation of the probability P(M|~G), discussed by Professor McGrew above – i.e. the probability of Matthew’s account being composed if there were no guard at Jesus’ tomb. Without further ado, here’s Alter’s scenario (emphases are mine – VJT):

…An obvious argument by doubters is that anyone could have removed the body before the tomb is discovered early Sunday morning by the several women. To circumvent this objection, Matthew is forced to invent a guard at the tomb. However, the presence of a guard will require a rational explanation. Consequently, Matthew is forced to invent the account of the Jewish leadership going to Pilate. But when is it possible for this visitation to have occurred? The earliest possible day would have been the Jewish Sabbath. However, a visit by the Jewish leadership on the Jewish Sabbath will have seemed unlikely to most knowledgeable readers or listeners to the text. Consequently, Matthew 27:62 obscures from its readers and listeners that this visitation occurs on the Sabbath: “Now the next day, that followed the day of the preparation, the chief priests and Pharisees came together unto Pilate.” This lie is necessitated because of Mark’s chronology (Mk 15:47; cf. Lk 23:54-56). That is, there is not enough time for the Jewish leadership to return to Pilate before the Sabbath and request a guard.

But why did the Jewish leadership need to see Pilate? There has to be a reason. Consequently, the previous lie necessitates Matthew inventing the idea that the Jewish leadership knew about Jesus’ prophecy that he will rise again after three days, “Saying, Sir, we remember that the deceiver said, while he was yet alive, After three days I will rise again” (Mt 27:63). How the Jewish leadership knew about this prophecy is not provided by Matthew.

Up to now, Matthew has explained why a guard is at the tomb, and he also provides information for his readers and listening audience that the guard stayed there for an undetermined length of time until the women arrive. This scenario now creates an even bigger problem. How can the women examine the tomb and verify that the tomb is empty if it is guarded by a Roman watch? Somehow these Roman soldiers must be eliminated from the scene. To resolve this problem, figuratively speaking, the angel descending from heaven and removing the stone, this terrifying the guard into a state of paralysis, kills two birds with one stone. Matthew has now explained how the tomb is open for the women to verify that Jesus’ body is missing and how the guard became immobilized to permit the women’s investigations at the tomb.

However, Matthew has now dug an even deeper hole for himself. Given that there is a guard at the tomb, why is there no record of what they saw? That is, why is there no record that the guard saw both the angel descending from heaven and the removal of the stone? To take care of this problem, Matthew invents the bribe: “And when they were assembled with the elders, and had taken counsel, they gave large money unto the soldiers” (Mt 28:12). However, this bribe creates yet another loophole. Would all the guards accept such a bribe, knowing that, if they were found out, it would mean their certain execution? Consequently, Matthew needs to invent another lie to protect his narrative. Thus, Matthew 28:14 states that the Jewish leadership will come to their assistance: “And if this comes to the governor’s ears, we will persuade him, and secure you.” [Note: Cassels (1902, 828) posits: “The large bribe seems to have been very ineffectual, since the Christian historian is able to report precisely what the chief priests and elders instruct them to say.”]

In brief, Matthew could have created a better lie. Every time he tells a lie it requires another and bigger lie to cover up the problem created by the previous lie. All these lies are ingeniously interwoven.

Professor McGrew read only my abbreviated version of the foregoing scenario, which did not impress him greatly. Here’s how I summarized it in a single paragraph (see also here):

…Alter suggests (2015, pp. 340-342) that the story was originally created in order to forestall an anti-Christian explanation for the empty tomb: maybe the reason why it was found empty is that Jesus’ body was stolen. To forestall that possibility, someone concocted a fictitious account of the Jewish priests going to Pilate and requesting a guard, in order to quell popular rumors that Jesus would rise from the dead on the third day. But that created a problem: if there were a guard at the tomb, then the women wouldn’t have been able to enter and find it empty. So in the story, the guard had to be gotten out of the way. This was done by inserting a terrifying apparition of an angel just before the women arrived at the tomb, causing the guards to fall into a dead faint, and conveniently providing the women with the opportunity to enter the tomb. And in order to explain why there was no public record of the guard seeing the angel remove the stone, the story of the guards being bribed into silence by the Jewish chief priests was invented. In short: the lameness of the guard story cannot be used to establish its authenticity. The story is an ad hoc creation, designed to forestall a common objection to the empty tomb accounts.

Professor McGrew is having none of it. He writes (emphases mine – VJT):

There is certainly something ad hoc going on in Alter’s treatment of the matter, but the problem lies in the methodology Alter employs here rather than in the story as told in Matthew’s Gospel. Start with a surmise — “Maybe it didn’t really happen.” Faced with the fact that there isn’t much reason to doubt it, make up a purely hypothetical motivation that someone might have had for inventing such a story: “Maybe Jesus’ body really was stolen, and they had to create a cover story for that fact.” Faced with the further problem that this particular cover story is hardly what one would invent to answer to that hypothetical state of affairs and could easily be contradicted by people on the ground in Jerusalem who knew the guards, ignore the problem and instead double down on creating hypothetical rationales for other parts of the story. “The guards have to be gotten out of the way so the women can enter …” Okay, why not just have Jesus’ resurrection itself knock them out instead of resorting to the awkward fabrication of their falling asleep? Simple questions like this suffice to show how specious such reasoning is. What historical narrative, however faithful, could not be dissolved (at least in the imagination of the critic) by the application of such methods?

Professor McGrew asks a fair question: why did Matthew feel the need to introduce an angel, rather than have Jesus himself roll back the stone and in so doing, knock out the guards? The reason, I would suggest, is that the story of the angel at the tomb was already part of the Christian tradition, as it is found in all four Gospels, in some form or other. Even in Mark’s Gospel, the young man dressed in a white robe, whose presence alarms the women, is meant to be an angel (compare with Luke’s description of two men in dazzling clothing). So the logical thing for Matthew to do would be to give the angel a more dramatic role – that of rolling back the stone – and an intimidating appearance (“like lightning”), so that the terrified guards fall into a faint and become “like dead men.” (Matthew does not say that they fell asleep; that was the lie they supposedly agreed to circulate.) So to my mind, Alter’s scenario is not as fanciful as Professor McGrew evidently thinks. It sounds plausible to me. The only caveat I would add is that we don’t know who invented the story: it could have been Matthew, or it could have been some members of an early Christian community, who composed it in to counter objections by hecklers.

Finally, in response to Professor McGrew’s objection that any historical narrative, even a reliable one, could be dissolved by the universal acid of Alter’s fanciful speculations, I would remind him of the point I made above: Matthew’s account of Jesus’ Passion and Resurrection is not just any old historical account: it is biased, heavily supernatural, and contains what appear to be numerous dramatic embellishments. Such an account therefore invites a special kind of scrutiny, which we would not normally subject other historical accounts to.

I shall lay down my pen here, as I have written enough. Over to you, readers.

Sounds like the poor get a raw deal, and the writer ignores parallel construction.

Math isn’t.

Probability and statistics are branches of math, phoodoo.

keiths,

Humans and chimps only share 16% of their DNA, because that’s how I feel.

Not math.

Franklin looks inside the box and says there are green frogs practicing kendo inside.

Devin looks inside the box and says there was an amazing light, that shone in three colors never seen by anyone before, and there was also a coupon for 20% off at Arbys.

They are all correct.

Not math.

phoodoo,

Franklin and Devin appear to be phoodoos. The moral of the story is: “If you want to run the coin flip experiment, don’t use phoodoos as observers.”

Let’s look instead at how Annelise would evaluate the probabilities at various times during the experiment:

1. Before the box is shaken, Annelise assigns a probability of 50% to an outcome of heads. Both possibilities are open, and because the coin is fair, the outcomes are equally likely.

2. After the box is shaken, she still assigns a probability of 50% to an outcome of heads, despite the fact that the event is in the past and the coin has already come to rest as heads or tails. Why? Because she doesn’t yet know which way the coin landed, and the probability she is expressing is an epistemic probability — that is, it depends on her state of knowledge at the moment. The coin could have landed heads or tails, and she has no reason to regard one outcome as more likely to have happened than the other. So she divides the probability equally between them and assigns a value of 50% to the “heads” outcome, just as Bronwyn does.

3. Annelise looks inside the box and sees that the coin has landed heads up.* Her state of knowledge has changed, and the (epistemic) probability of the “heads” outcome is now 100%. The probability of the “tails” outcome is zero.

At every stage, the epistemic probability depends on Annelise’s state of knowledge, and she revises her initial probabilities when that state of knowledge changes — that is, when she acquires new and relevant information by peeking inside the box. Bronwyn doesn’t peek, and so her probabilities remain unrevised at 50%.

Annelise’s answer is correct given her state of knowledge, and Bronwyn’s answer is correct given her state of knowledge. They are different, but each is correct. Epistemic probability is dependent on the observer’s state of knowledge.

*There is technically a slight, nonzero probability that she’ll misread the result, mistaking “heads” for “tails” or vice-versa, but the example assumes 100% accuracy. It could easily be modified to account for a nonzero error rate.

There’s a classic and counterintuitive example of epistemic probability that’s worth mentioning here.

You meet an honest stranger and the two of you are chatting.

1. You ask her how many children she has, and she answers “two”. What is the probability that both are boys?*

2. You ask her if at least one of her two children is a boy, and she answers “yes”. What is the probability that both are boys?

3. You then ask if her oldest child is a boy, and she answers “yes”. What is the probability that both are boys?

These are epistemic probabilities, so the answers depend on your state of knowledge at each point.

In #1, you know only that she has two children. Therefore, the possibilities are GG, GB, BG, and BB, where the first letter represents the older child. The possibilities are equiprobable, and the BB case is one out of four, so the probability that both children are boys is 1/4.

In #2, you know that at least one child is a boy. That rules out the GG case. The remaining possibilities are equiprobable, and the BB case is one out of three, so the probability that both children are boys is 1/3.

In #3, you know that the oldest child is a boy. That rules out the GG and GB cases. The remaining possibilities are equiprobable, and the BB case is one out of two, so the probability that both children are boys is 1/2.

Nothing changed but your state of knowledge regarding the two children. Epistemic probabilities depend on your state of knowledge, and they are therefore observer-dependent.

*The example assumes that every child is either a boy or a girl, and that boys and girls are equiprobable.

keiths,

keiths, you are really struggling with this. I don’t think you understand how statistics work, but you are trying to act as if you do.

There are no statistics to determine the truth of Bible stories. You keep wanting to refer back to coin flips or boys versus girls, or other matters where we know prior to the event, the possible number of outcomes. The bible stories have no such numbers. You can’t say there is a 50% probability to start off with, now lets calculate if the outcome fits the known probabilities of outcomes. Your analogies are completely misguided.

Its not a coin toss, its the word of the people who wrote it, and you don’t have any probabilities to calculate the truthfulness or accuracy of their testimony. Its not math, in the same way that a trial does not use math to determine a witnesses voracity. They use hunches, they use facts involved, but they don’t use math.

Give up the coin tosses Keiths, hunches are not coin tosses.

Not math.

All very nice, but what is the chance a stranger is honest.

Or more to the point, what are the odds that a book of religious revelation is reliable?

What is wrong with you? According to the principle of indifference, which rather obviously applies in this case, there is a 1 in 2 chance that you are full of BS.

Not really.

You define C as the outcome of a yet-to-be-done fair coin flip. You can’t be trusted.

You define new event F. This is no more believable than your previous attempt to define event E.

Mung, to phoodoo:

Based on phoodoo’s performance in this thread, I think you should revise that probability sharply upward.

Epistemic probabilities are dependent on knowledge. Score one for FMM!

Wrong. An event that is certian to occur, or an event that is certain to not occur, is not “probable” in any meaningful use of that term.

You have a better explanation for how they got out?

I revised the probability that you have a sense of humor upward. 🙂

Mung:

Not sure what your point is. Neither heads nor tails is certain to occur when you shake the box.

After the box is shaken and the coin comes to rest, the outcome is fixed, but it’s still not certain. As far as you know, it could be either heads or tails. You aren’t certain which outcome occurred. It’s when you look inside the box (assuming you aren’t a phoodoo) that you become certain.

What probability do you assign to “neither heads nor tails” given that you have already assigned a probabilty of .5 to heads and a probabilty of .5 to tails?

Why have you, by definition, excluded that possibility?

ETA: Either heads or tails is certain. Inevitable, really.

Mung,

You are trying so hard to misunderstand.

How about answering the three questions I posed in the two-children example? That might help me to figure out where you’re going wrong.

Mung:

This is where logical operators and grouping with parentheses come in handy.

Assuming the coin can’t land on edge, and that we aren’t in a weightless environment, etc.:

1. (Either heads or tails) is certain.

2. (Neither heads nor tails) is impossible.

3. ((Heads is certain) or (tails is certain)) is false.

4. When I wrote “Neither heads nor tails is certain”, my meaning was “Neither (heads is certain) nor (tails is certain)”.

petrushka,

Pretty high, when the topic is the number of children she has and whether they are boys or girls.

Vincent is examining a specific claim, and the thread title gives away his conclusion:

Whether or not you agree with his conclusion, there’s nothing wrong with asking the question or trying to reason about it probabilistically.

As I put it to Alan:

keiths,

Right, the number is whatever you think it is. See petrushka ?

Just decide what is your feeling about the truthfulness of mothers telling strangers how many kids they have, then that’s how you come up with the number. Or if you like you can also take two times the square root of pi if you feel that’s a better number. Or tell your dog to bark and then divide how many times he barks before he gets disinterested, and that’s your probability. If you like it.

The good news is you can never be wrong. Math without all the pressure. Keith says it’s high, then it’s high. You say it’s low then it’s low.

It’s a great new way to get kids hooked on math who may not have had an aptitude for it before.

I suggest as alternatives:

“ejected”

“launched”

“catapulted”

I had no idea exegesis could be this much fun!

The Greek word to describe resurrection is ANASTASIS literally means ‘raising up’, or ‘rising… So the author of the original text could have used the word “anastasis” to describe both resurrection from the dead and the corpses ‘raising up’, or ‘rising out of the graves due to an earthquake…

What’s the mathematical probabilities of the guards taking a coffee break?

Was there a coffee shop in the area? How about fast food joint like lamb kebab on the run? 😉

There’s nothing wrong with reasoning about it if you have some numbers. Or some examples from other sources.

Just a quick driveby to say excellent parody. Made me laugh.

Regarding Vincent’s question “Why there probably wasn’t a guard at Jesus’ tomb”, I have been musing on that. The dereliction-of-duty fear, for instance. Was there a written performance standard for tomb guards? Was capital punishment the norm for such transgressions? Was it a recognised profession? Was there much call for business? Or were bums on street corners recruited ad hoc? I mean, in ancient Egypt and in other cultures (Sutton Hoo burial) some valuable stuff got stashed away with the body but in Palestine, was that the tradition? Who paid the guards, who trained them, equipped them, (and quis custodiet?) And why are such questions different from wondering whether there was icing sugar on Edmund’s Turkish delight?

Why did the Sanhedrin think Jesus’ followers would try and dispose of the body to give (who would know?) the impression he had been transported off to heaven by his father. It seems these guys were almost prescient. And what numbers shall we assign to our probabilities? And how shall we test our results?

Sorry, that was a bit stream-of-consciousness, must dash.

Ninja’d

petrushka,

Right.

I wrote

My approach is to immediately discount any aspect of a historical claim that would violate observed reality and examine what is left on the merits. I don’t need probability theory to help me in that endeavour. And neither do you if I understand your “informally” remark correctly. which responds to your question.

Apologies for suggesting you used “informally”.

That was me paraphrasing your “what people do all the time without realising it”. No doubt you can tell me at great length why “informally” does not encapsulate that idea.

Are you telling me hat the guards stayed up all night without coffee or a doughnut or food? 😉

Please stop embarrassing yourself.

The “author of the original text” could have used ANASTASIS (which, btw means the state of being resurrected). Matthew does use ANASTASIS four times, all while discussing an attempted gotcha by the Sadducees about which husband gets to keep their (serially) shared wife when they ALL get resurrected. It’s a puzzler. But notice how it refers to a state, and not the process of getting resurrected…

So yeah, he could have used ANASTASIS, but, as I already explained to you, HE DID NOT.

He used ἠγέρθησαν, which he also used (in 14:2, ἠγέρθη) to describe John the Baptist’s resurrection and his own resurrection (in 16:21 ἐγερθῆναι). Nobody was getting thrown anywhere.

Yikes!

I missed that … sorry I will wait for the email…

BTW: what’s the original text you are referring to? What’s the source so that there are no misunderstandings if I dig out something else…

ETA: you realize that we are debating the possibility of one resurrection over the impossibility of others, right?

Resurrection of some sort is the foundation of most faiths… people who witnessed them were willing to die for their faith because of the resurrection hope…

phoodoo,

If you put it like that I largely agree with you.

On the risk (probability?) of boring you all to death about my old job, when we risk hydrocarbon prospects we actually risk the model that we have adopted to describe the subsurface. If we were to adopt a different model, the probabilities would quite possibly be very different.

In the case of this Bible story the same thing holds. If our mental model is that the Bible is completely fiction we would estimate the probability of the guard being there very different than if we consider the Bible largely historic but with some embellishments; if we consider the Bible to be 100% inerrant we would estimate the probability different again.

Our a priori assumptions will make a huge difference to the outcome.

J-Mac,

Corneel:

They must have been catapulted all the way into the city, since the author of Matthew says they “went into the holy city and appeared to many people.”

Makes perfect sense, J-Mac. The catapulted corpses rained down on Jerusalem, where they were seen by many people. That sort of thing happens all the time in modern earthquakes.

petrushka:

And there’s nothing wrong with supplying your own estimates, as long as you can defend them. As faded_Glory described it, in the context of drilling risk:

As I’ve said, I haven’t looked closely enough at Vincent’s argument to see if I agree with his probability estimates. However, there is nothing wrong with making such estimates and applying them, as faded_Glory’s example shows.

Regarding your claim that numbers are needed, I disagree. The goofy mass resurrection story in Matthew 27 is extremely improbable, and I’m able to defend that assessment without using any numbers. Probabilistic reasoning is still probabilistic reasoning even when it doesn’t employ numbers.

faded_Glory:

Yes, and bad assumptions and estimates will lead to untrustworthy results. It’s the GIGO (garbage in, garbage out) principle. That’s why it’s beneficial, in the context of a debate, for the disputants to make their assumptions and estimates explicit so that they can be challenged.

I put it this way to phoodoo:

Of course the above applies not only to Bayesian inferences but to probabilistic reasoning in general.

keiths,

Yes you can call it unlikely, or I can call it likely using my own criteria, and neither of us is right or wrong.

But what V J said was that someone else’s math on the subject was incorrect. That is silly right from the beginning because no math is involved. Assigning numbers is not the same as doing math. It’s as if I said blue is my number one favorite color, then green is my number two favorite, and red number three.

There can be no claims of incorrect math

phoodoo,

Estimates can be reasonable, and they can be unreasonable. See my GIGO comment above.

Mathematically literate folks know the axioms of probability, including the requirement that probabilities lie on the interval [0,1]. They wouldn’t pull a phoodoo and assign two times the square root of pi as a probability.

The bad news is, you just demonstrated otherwise.

Alan:

I responded to that here and here.

Hi Vincent,

In your earlier thread on Alter’s book, you wrote:

And:

But you also mentioned the sensus divinitatis, as well as writing:

My impression of you is that like me, you won’t be satisfied with your faith in the long run unless you can justify it with the head. I couldn’t, and gave up my faith with reluctance. How do you see it playing out for you? Do you think your faith will last if your head can’t be persuaded of what your heart wants to believe?

According to whom?

Math isn’t about being reasonable, its about being true.

You are known as someone who will fail to ever acknowledge your errors of argument. You will argue any point for as long as you can, because your personality doesn’t allow you to do otherwise. But you picked a poor hill to defend this time Keiths. Probability of truthfulness isn’t a math problem, its a hunch.

If there is no right and no wrong, its feelings written as a number, not math. You chose the hill, but this time you will die on that hill trying to prove otherwise.

You ask as if it’s all just a matter of opinion, and that nobody could ever claim to have made a reasonable estimation, or show another estimation to be unreasonable.

But I doubt you actually think this is the case. The fact that you and I might disagree on what is a reasonable estimation (whatever it is) does not actually serve to show that there is no such thing as a reasonable estimation. We may both be biased in our various ways in some argument, and for that reason we may fail to reach agreement. But some times a third party not intellectually or emotionally invested in the discussion can get an “outside” view of our various arguments and decide in a much more dispassionate and objective fashion which (if any) of our estimations are reasonable.

What is a reasonable estimation of the likelihood that God wants all humans to levitate into the upper atmosphere and then axphyxiate? Well, I would argue that given that if God exists, and is supposed to be omnipotent and his will is therefore guaranteed to occur, and that this event does not seem to occur, my estimation is that the likelihood that God wants this to occur is zero.

Am I to take it that you think there is no such thing as even approaching an objectively reasonable estimation of the probability that God wants this to occur? Correct me if I’m wrong but I think you’d agree there are objectively reasonable and unreasonable estimations.

There is another issue at work here, which are situations with more ambiguity and where we lack data to make good estimations. We might still DO estimations of course, but whether or how reasonable they are, in such situations, will have a higher degree of subjectivity involved. This is not to say they can’t be done, and that some estimations even given ambiguous data still can’t be unreasonable. It is still possible that we can go to the extremes and see that they involve question-begging assumptions.

To pick an example, some would argue that an estimation of the prior probability of the resurrection might be set at zero. The problem here is that, while that may make some empirical sense (supposing we know that no one else has ever been supernaturally resurrected by God ), it begs the question against the resurrection. With a prior probability of zero, the probability of the resurrection can never be anything but zero, no matter how good the evidence is. That would, in my opinion, be an unreasonable estimation of the prior probability. But I’d also like to think of myself as a person who could be convinced otherwise if the evidence is good enough. So even I as an atheist could agree to set the prior probability to at least one in the number of people who have ever lived to reflect that there is some possibility that God actually has done so in this case. That would be approximately one in one hundred billion. 10^-11

Likewise I think we can also set an unreasonably high probability even given ambiguous data. Suppose that out of the 100 billion people who ever lived, we only knew about how 5 billion of them lived and died, and we strictly don’t know how the rest died, or what if anything happened to them after they died. A theist might then argue that it is possible that God supernaturally resurrected all the remaining 95 billion we don’t what happened to after they died. So that theist could set the prior probability of resurrection by God to 95/100, or 95%.

I think that too is an unreasonable estimation, because I think it is reasonable to suppose the vast majority of these people lived lives very much like our own. They were born, grew up, had families, grew old, or got sick, or got into accidents or wars, and then died and were buried, never to be seen again(in this life at least). And if there’s a God and an afterlife, they might just have gone on to live in that afterlife. One could even argue that, if 95% of the 100 billion people who ever lived were resurrected by God, it wouldn’t really make Jesus special either, or prove much in way of his divinity and sacrifice.

Perhaps you still disagree, but I think these arguments show that the situation is not as hopelessly subjective as you are arguing here. We don’t have to throw the baby out with the bathwater just because there are some, well, unreasonable crackpots among us that refuse to be convinced or accept what is or isn’t reasonable/unreasonable estimations.

Rumraket,

You are conflating the notion of making a guess, with doing math. They are not the same thing at all.

Thus if one claims that another’s math is wrong, when it comes to making a guess, that claim is bullshit.

Your problem isn’t with the math, it is with the numbers that people attach to the strenght of their judgement. And that is fair enough, up to a point.

If you had to express ‘somewhat unlikely’ as a probability number, what would you chose? 5%? 20%? 50%? 75%?

Give it a shot – put a range on it if you want.

Go on, you can do it.

Hi keiths,

Fair question. I have pretty much given up the enterprise of arguing for the historicity of the Resurrection on purely historical grounds. There are just too many unknowns. For my part, I think the plausibility of the Resurrection rests on a subjective assessment of the character of Jesus, in addition to an impartial assessment of the evidence relating to Jesus’ burial and post-mortem apparitions. For someone who believes in God and who believes that Jesus was not deluded in his cosmic claims about himself, the question boils down to whether God would have deemed Jesus resurrection-worthy. My own answer is in the affirmative.

I will say, though, that if Jesus had never made any exceptional claims about himself, and had never claimed that he would be vindicated after his death, then it would be prudent for an impartial historian to set aside the fact that his body was never found, and that some of his disciples claimed to have seen and spoken with him after he died. These claims only make sense against the larger background of what Jesus did during his ministry, and what he said about himself. Cheers.

Excellent.

This is a much better approach than trying to argue from the truth of the resurrection to the existence of God or the divinity of Jesus.

An even better approach is to treat the Gospel narrative as simply a reporting of the Good news of what God did for us and not as any sort of argument whatsoever.

And what the OT says about the Messiah and about things like the Exodus and what we understand about God from philosophy and personal experience.

It’s all a package deal, you can’t break it up into pieces and argue one point in isolation as if the rest does not matter.

I think that what happens with folks like keiths who abandon Christianity is that they never really trusted God. They trusted that some event happened or that some book was true or what their parents told them or some feeling that they had.

All of those things are Idols when we put our faith in them in the place of God.

peace

vjtorley,

I read the odds are 42.39 percent. Perhaps Jock would confirm the math.