[For a brief explanation of my “An A-Z of Unanswered Objections to Christianity” series, and for the skeptical tone of this article, please see here. I’m starting my A-Z series with the letter H, and I’ll be zipping around the alphabet, in the coming weeks.]

In this article, I take aim at the Christian teaching that there was a special moment in history at which humans, who were made in the image of God, came into existence, and that a sharp line can be drawn between man and beast. I argue that on purely scientific grounds, it can be shown that such a view is highly unlikely. If the scientific arguments I put forward here are correct, then Christianity is in very big trouble.

|

KEY POINTS

Christianity is committed to the view that humans, who are the only animals made in the image and likeness of God, came into existence at a fixed point in time – a “magic moment,” if you like. However, anthropologists find this picture wildly implausible, for two main reasons. First, science has not identified any “sudden spurts” in the evolution of the human brain over the past four million years. While there appear to have been a couple of periods of accelerated evolution, these lasted for no less than 300,000 years. As far as we can tell from the fossil record, there were no overnight improvements in human intelligence. Second, when scientists examine the archaeological record for signs of the emergence of creatures with uniquely human abilities, what they find is that there are no less than ten distinct abilities that could be used to draw the line between humans and their pre-human forebears. However, it turns out that these ten abilities emerged at different points in time, and what’s more, most of them emerged gradually, leaving no room for a “magic moment” when the first true human beings appeared. Finally, recent attempts by Christian theologians to evade the force of this problem by redefining the “image of God” not in terms of our uniquely human abilities (the substantive view of the Divine image), but in terms of our being in an active relationship with God (the relational view) or our special calling to rule over God’s creation (the vocational or functional view) completely fail, because neither our relationship with God nor our domination over other creatures defines what it means to be human: they are both consequences of being human. What’s more, humans only possess these qualities because of underlying abilities which make them possible (e.g. the ability to form a concept of God or the ability to invent technologies that give us control over nature), so we are back with the substantive view, which, as we have seen, supports gradualism. The verdict is clear: contrary to Christian teaching, no sharp line can be drawn between man and beast, which means that the Biblical story of a first human being is a myth, with no foundation in reality. And if there was no first Adam of any kind, then the Christian portrayal of Jesus as the second Adam (1 Corinthians 15:45-49) makes no sense, either. I conclude that the difficulty posed above is a real one, which Christian apologists ignore at their peril. |

One of the key problem areas for Christian belief relates to human origins. Let me state upfront that I will not be discussing human evolution in this post, as Christians of all stripes (Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox) readily agree that God could have used the natural evolutionary process to make the first human beings (or their bodies, at any rate), had He wished to do so. The only point of disagreement is an exegetical one: namely, whether the Biblical account of God creating Adam from the dust of the ground was intended to be taken literally, in the first place. (Most Christians now think it wasn’t.) Nor am I going to wade into the debate as to whether humanity sprang from a single original couple (Adam and Eve) as Christians have traditionally believed, or a much larger stock of several thousand people, as some genetic studies have suggested. (For a fair-minded summary of the current state of the evidence, see the article “Adam and Eve: lessons learned” [April 14, 2018] by Dr. Richard Buggs, Professor of Evolutionary Genomics at Queen Mary University of London.) In recent years, Christians have proposed many ingenious ways of reconciling Adam and Eve with the findings of evolutionary biologists, and Dr. Joshua Swamidass’s recent book, The Genealogical Adam and Eve: The Surprising Science of Universal Ancestry (IVP Academic, 2019), provides an excellent overview of the solutions that have been proposed to date, including a new proposal by Swamidass himself. On top of that, there is an ongoing controversy (see also here) as to whether the author of Genesis 2 ever intended to teach the descent of human beings from a single original couple. The name “Adam,” for instance, is generic: it means “man,” while “Eve” means “life.” For these reasons, I maintain that the issues of human evolution and monogenesis (the descent of all humans from Adam and Eve) pose no existential threat to Christianity: there is room for a legitimate diversity of interpretation of the Scriptures on these matters.

Instead, the problem I’m going to discuss in this post is a much more fundamental one: namely, the question of whether there really was a first generation of human beings, or in other words, whether there was a fixed point in time at which humans came into existence – a “magic moment,” if you like. According to Judaism, Christianity and Islam, there must have been one. But according to science, there couldn’t have been one. And if the scientists are right, then Christianity is in very big trouble. Please allow me to explain.

| MAIN MENU

Introduction. Humans and beasts: a clear divide? The Bald Man paradox A. The steady increase in human brainpower over the past four million years: where do you draw the line? B. The “Ten Adams” problem An Archaeological excursus 2. Fire-controller Adam 5. Spear-maker Adam 8. Linguistic Adam 9. Ethical Adam C. Another way out for Christian apologists: Redefining the image of God? Postscript: Was Adam an apatheist? |

Introduction. Humans and beasts: a clear divide? The Bald Man paradox

RETURN TO MAIN MENU

The gentleman pictured above surely needs no introduction. I have chosen him because he exemplifies an old paradox from antiquity: the Bald Man paradox, first posed by the Greek philosopher Eubulides of Miletus. It goes like this:

A man with a full head of hair is obviously not bald. Now the removal of a single hair will not turn a non-bald man into a bald one. And yet it is obvious that a continuation of that process must eventually result in baldness.

The paradox arises because the word “bald,” like a host of other adjectives (“tall,” “rich,” “blue” and so on), is a vague one. Most scientists would say that the word “human” is equally vague, and, like the word “bald,” has no clear-cut boundaries. On this view, there never was a “first human” in the hominin lineage leading to modern humans, for the same reason that there never was a definite moment at which Prince William went bald. Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins explains this point with admirable lucidity here:

Or as Charles Darwin succinctly put it in his work, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871, London: John Murray, Volume 1, 1st edition, Chapter VII, p. 235):

“Whether primeval man, when he possessed very few arts of the rudest kind, and when his power of language was extremely imperfect, would have deserved to be called man, must depend on the definition which we employ. In a series of forms graduating insensibly from some ape-like creature to man as he now exists it would be impossible to fix on any definite point when the term ‘man’ ought to be used.”

However, Judaism, Christianity and Islam all insist on a clear, black-and-white division between human beings and other animals. Humans are made in the image and likeness of God; beasts are not. Humans have spiritual, immortal souls that are made to enjoy eternity with their Creator, in Heaven; beasts will never go to Heaven. (Even Christians who believe in some sort of immortality for animals nevertheless acknowledge that only humans will get to behold God’s glory, face-to-face.) There are moral and political differences between humans and other animals, as well. Humans have inalienable rights, and in particular, an inviolable right to life; beasts, on the other hand, may be killed for food in times of necessity. (Indeed, most Christians would say that animals may be killed for food at any time.) Humans, especially when they are mature and fully developed, are morally responsible for their actions; beasts are not. We don’t sue chimps, as we don’t consider them liable for their actions, even when they do nasty things like kill individuals from neighboring communities, because we presume they can’t help it: they are merely acting on innate tendencies. And for the same reason, we believe God doesn’t punish them for the destructive things they do. There is no hell for chimpanzees – even vicious ones that cannibalize infants (as some do). Finally, human beings are believed to possess certain special powers which other animals lack. For some Christians, such as Aquinas, what distinguishes humans from other animals is the godlike faculty of reason; for others, such as John Wesley, it is not reason, but the ability to know, love and serve God that makes us special. However, all Christians agree that humans are in a league of their own, mentally and spiritually, and that they have certain powers which the beasts lack. In other words, there is a clear-cut distinction, on a metaphysical level, between man and beast.

What this means is that even Christians who believe in evolution are nonetheless mind creationists, to borrow a term from the philosopher Daniel Dennett, who used it in his book, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea (Simon & Schuster, 1995) and his more recent paper, “Darwin’s ‘strange inversion of reasoning'” (PNAS, June 2009, 106 (Supplement 1) 10061-10065) to refer to thinkers (both theistic and atheistic) who refuse to accept that the human mind is the product of a blind, algorithmic process: natural selection. Christians believe that on a spiritual level, humanity literally sprang into existence overnight, due to the creative action of God. And since what makes us human is the highest and noblest part of us (call it mind, spirit, the human soul or what you will), it follows that if humans are radically distinct from the beasts, then they cannot have emerged from the beasts gradually – which means that the distinctively human part of our nature must have appeared instantly. Thus, on the Christian view, the human mind or spirit appeared suddenly, and there was a first generation of creatures possessing a human mind or spirit. These were the first true human beings. Before that, there may have been other creatures looking very similar to us, but it is not merely our physical appearance that makes us human. What distinguishes human beings is the possession of certain unique, God-given powers that other creatures lack. And it is these powers that appeared in the blink of an eye, according to Christian doctrine.

Catholic physicist Stephen Barr is a sophisticated exponent of the modern Christian view, which seeks to combine biological evolution with the religious belief in a spiritual soul. Writing in the journal First Things (April 2017), Barr acknowledges that biological species (such as cats and Homo sapiens) do not appear overnight, but posits a special intervention by God in the course of prehistory, in which God infused a spiritual soul into some anatomically modern humans, endowing them with rationality (and, he later suggests, language):

It is quite consistent to suppose that a long, slow evolutionary development led to the emergence of an interbreeding population of “anatomically modern humans,” as paleo-archeologists call them, and that when the time was ripe, God chose to raise one, several, or all members of that population to the spiritual level of rationality and freedom.

I’d now like to explain why biologists find this picture utterly incredible. There are two major reasons: first, although human brainpower has increased fairly rapidly over the past four million years, science has not identified any “sudden spurts” in the evolution of the brain (unless you call 300,000 years sudden); and second, there are no less than ten distinct human abilities that could be used to draw the line between man and beast, but it turns out that all of them emerged at different points in time (so which one do you pick?), and in any case, all of them (including language) emerged gradually, over many thousands of years. (Acheulean tools are the only exception, and even these may have been invented on multiple occasions.)

At this point, some Christians may object that science is, by virtue of its very methodology, incapable of identifying the emergence of the human mind or spirit during the prehistoric past. Souls don’t leave fossils, after all. That may be so, but it is indisputable that humans (who are alleged to possess spiritual souls) behave in a strikingly different way from other creatures: after all, it is humans who hunt chimps, perform research on them and cage them in zoos, not the other way round. If the human soul is real, then, we should certainly expect to find traces of its behavioral manifestations in the archaeological record. And during the past few decades, archaeologists have become remarkably proficient at deciphering those traces. They can tell us, for instance, what level of planning would have been needed to make prehistoric tools, and whether the makers of those tools would have required language in order to teach others how to fashion them. They can tell us about the origin of human co-operation, and whether prehistoric communities engaged in altruistic behavior. They can tell us a lot about the origins of art and religion, as well. So I would invite Christians to look at the evidence with an open mind, and draw their own conclusions.

================================================================

A. The steady increase in human brainpower over the past four million years: where do you draw the line?

RETURN TO MAIN MENU

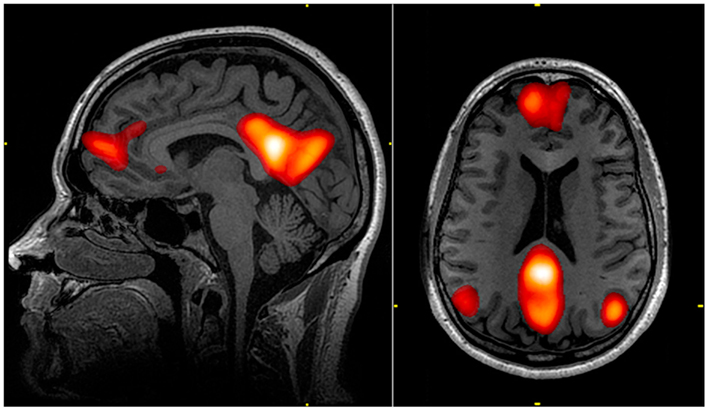

Magnetic resonance imaging, showing areas of the brain comprising the default mode network, which underlies our concept of self and is involved in thinking about other individuals. Image courtesy of John Graner, Neuroimaging Department, National Intrepid Center of Excellence, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center and Wikipedia.

The first argument I’d like to put forward is that the fossil evidence, which is based on the evolution of the human brain, strongly suggests that human intelligence has steadily increased over the past several million years, without any “quantum leaps,” as you would expect if human mental capacities had literally appeared overnight. Now, I am sure that some readers will be thinking: “The mind is more than just the brain. Just because the human brain increased gradually in size, it doesn’t follow that our mental capacities increased gradually.” But regardless of whether you’re a dualist or a materialist, the fact remains that a great thinker requires a great brain. In his book, Intellect: Mind Over Matter (Chapter 4), the Aristotelian-Thomist philosopher Mortimer Adler (1902-2001) argued that “we do not think conceptually with our brains,” as an individual organ such as the brain is incapable of embodying universal meanings, such as the meaning of “human” or “triangle” or “machine”; but at the same time, Adler was happy to acknowledge that “we cannot think conceptually without our brains.” Adler’s first point invites the obvious objection that an individual soul would be in no better position to apprehend universal meanings than an individual brain; however, his second point is surely a valid one. Allow me to explain why.

Regardless of whether or not it is capable of embodying semantic meaning, it is certainly true that the human brain, with its 86 billion neurons, is a very powerful information processor. Your brain has to handle a vast amount of information every second, in order that you can remain alive and consciously aware of what’s going on around you. You would be unable to think rationally unless your brain possessed the ability to process sensory data from your surroundings, organize that data as information, and store that information in your working memory and (if it’s useful) your long-term memory. As a rational human being, you also need to be able to plan ahead – a task that requires you to keep several things in mind at once: the sequence of steps you need to follow, in order to achieve your goal. Multi-tasking is often required, as well: very few tasks follow a simple, linear A -> B -> C -> D sequence. The ability to actively recall information you’ve previously learned whenever you need it is also vital. In other words, if you want to survive as a rational human being, then any old animal brain won’t do; you’ll need a pretty high-powered one, with a high information-processing and storage capacity, and a high degree of inter-connectivity as well.

“What about the concept of God?” the reader may object. “Surely neural hard-wiring is no help at all when it comes to entertaining the concept of an immaterial being. Why should you need a special kind of brain for that?” However, it turns out that having a concept of God (or gods) requires a highly sophisticated brain, too. To believe in God, you first need to have a concept of self. You also need to possess a theory of mind: a belief in other agents, having desires and intentions of their own. Additionally, you need to be able to entertain the notion of spirits or invisible agents, who are capable of controlling events from the top down. Finally, you need to have the concept of a Master Invisible Agent, Who made the entire universe (“heaven and earth”) and Who keeps the whole show running. While the neural underpinnings of belief in God are still being investigated, scientists already know that there are several specific brain regions associated with simply having a concept of self and a theory of mind (which most animals lack). Together, these regions comprise what is known as the brain’s default mode network (pictured above). The default mode network is the neurological basis for one’s concept of self: it stores autobiographical information, mediates self-reference (referring to traits and descriptions of oneself) and self-reflection (reflecting about one’s emotional states). It’s also involved in thinking about others – in particular, in having a theory of mind, understanding other people’s emotions, moral reasoning, social evaluations and social categories. On top of that, it’s utilized in tasks such as remembering the past, imagining the future, episodic memory and story comprehension. The default mode network is comprised of an interconnected set of brain regions, with the major hubs being located in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and precuneus, the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and the angular gyrus. Scientists have discovered, for instance, that increased neural activity in the medial prefrontal cortex is related to better perspective-taking, emotion management, and increased social functioning, while reduced activity in the above-mentioned areas is associated with social dysfunction and lack of interest in social interaction. And according to a recent neuroimaging study conducted by Raymond L. Neubauer (Religion, Brain and Behavior, Volume 4, 2014, Issue 2, pp. 92-103), “Results show an overlap between prayer and speaking to a loved one in brain areas associated with theory of mind, suggesting that the brain treats both as an interpersonal relationship. These brain areas are also associated with the default mode network, where the mind evaluates past and possible future experiences of the self.”

The point I’m making here is that if the ancestors of modern human beings underwent some kind of “Great Leap Forward” in their mental or spiritual capacities at some point in the past (as Christians suppose), their brains would have had to have been radically transformed as well. That holds true, regardless of whether you’re a materialist or a dualist.

Putting Christian “mind creationism” to the test

Above: The philosopher Daniel Dennett, who coined the term “mind creationists” to describe thinkers who either doubt or deny that the human mind is the product of natural selection (Jerry Fodor, Thomas Nagel, and the Christian evolutionary paleontologist, Simon Conway Morris), or who accept that the human mind is a biological machine, but deny that it arose as a result of purely algorithmic, step-by-step processes (John Searle, Roger Penrose). Image courtesy of Dmitry Rozhkov and Wikipedia.

——————–

I’d now like to present two hypotheses: the hypothesis that the human mind, spirit or rational soul (i.e. whatever capacity it is that distinguishes us from the beasts) appeared overnight, and the hypothesis that this capacity evolved gradually. I’m going to refer to these hypotheses as Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2. The two hypotheses make different predictions. A quantum leap, or saltation, in the human brain’s information-processing capacity at some point during the past few million years, would tend to favor Hypothesis 1, as it would suggest that at some point in the past, the brains of hominins suddenly became suitable for the exercise of human agency. [Note: Hominins are defined as creatures such as Ardipithecus, Australopithecus, Paranthropus and Homo, which belong to the lineage of primates that broke away from the chimpanzee line and led eventually to modern humans, although many branches died out along the way, without leaving any descendants. The term ‘hominid’ used to have the same meaning that ‘hominin’ now has, but now includes humans, chimpanzees, gorillas and orang-utans, as well as all their immediate ancestors.] Even if you believe that our highest human capacities transcend the brain, you would still be heartened by the discovery of a sudden increase in the brain’s information-processing ability over the course of time, because a great thinker still requires a great brain, even if it’s not the brain itself that does the thinking. By contrast, a gradual increase in the human brain’s information-processing capacity over time would tend to favor Hypothesis 2, that our ancestors didn’t become human overnight, and that there’s no sharp line dividing man from beast, but a continuum instead.

Please note that I am not speaking of “proof” or “disproof” here, but merely of evidence. It’s certainly possible that the capacities that make us human emerged suddenly, even though the human brain’s information-processing capacity increased gradually: maybe there was a “critical point” at which our capacities suddenly manifested themselves, for instance. Who knows? Nevertheless, the discovery that there have been no “sudden spurts” in human brainpower over the past few million years favors Hypothesis 2, because it is a fact that Hypothesis 1 can account for only by making the ad hoc assumption that the human brain has a critical mass, whereas Hypothesis 2 requires no arbitrary assumptions in order to explain this fact.

Finding a good yardstick to measure the intelligence of our prehistoric forebears

So, which hypothesis does the scientific evidence support? To answer that question, we need to find a good yardstick to measure the brain’s information-processing capacity. Just as a high-capacity computer needs a lot of power to stay running, so too, a human brain needs a high metabolic rate, in order to continue functioning normally. Now, for any species of animal, the brain’s metabolic rate is mainly related to the energetic cost of the activity occurring in its synapses. For that reason, metabolic rate is widely thought to be a better measure of an animal’s cognitive ability than simply measuring its brain size.

The carotid canal (shown in green, bottom right) is the passageway in the temporal bone through which the internal carotid artery enters the skull from the neck. There is one on each side of the base of the skull. Professor Roger Seymour contends that the width of this canal in the skulls of prehistoric hominins serves as a useful measure of the information processing capacity of their brains – or in other words, how smart they were. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

It turns out that human brains have a pretty high metabolic rate: indeed, the human brain uses no less than 20% of the body’s energy, despite the fact that it makes up only 2% of the body’s mass. If we look at other primates, we find that apart from some small primates, which are known to have a high brain mass to body mass ratio (for example, ring-tailed lemurs [average weight: 2.2 kg] and pygmy marmosets [0.1 kg]), the brain of a typical primate typically uses only 8 to 10% of its body’s energy, while for most other mammals, it’s just 3 to 5%. So, what about the brains of human ancestors? How much energy did they use, and what were their metabolic rates? We need no longer speculate about these questions; we have the answers. As Roger Seymour, Emeritus Professor of Physiology at the University of Adelaide, Australia, explains in an online article on Real Clear Science titled, “How Smart Were Our Ancestors? Blood Flow Provides a Clue” (January 27, 2020), we now possess a handy metric for measuring the metabolic rate for the brains of human ancestors, over the last several million years. In a nutshell: the arteries that carry blood to the brain pass through small holes in the base of the skull. Bigger holes mean bigger arteries and more blood to power the brain. By measuring the size of the holes in the base of the skulls of fossil humans, we can estimate the rate of blood flow to their brains, which in turn tells us how much information they were capable of processing, just as the size of the cables indicates how much information a computer is capable of processing.

Professor Seymour and his team performed these measurements for Ardipithecus, various species of Australopithecus, Homo habilis, Homo erectus and his descendant, Heidelberg man, who’s believed by some experts to be the ancestor of both Neanderthal man and Homo sapiens. (Others think it was Homo antecessor [see also here], who was older and somewhat smaller-brained than Heidelberg man, but whose face was more like ours. Unfortunately, we don’t yet have a complete skull of this species.) Seymour summarizes the findings: “The rate of blood flow to the brain appears to have increased over time in all primate lineages. But in the hominin lineage [that’s the lineage leading to human beings – VJT], it increased much more quickly than in other primates.” He adds: “Between the 4.4 million year old Ardipithecus and Homo sapiens, brains became almost five times larger, but blood flow rate grew more than nine times larger. This indicates each gram of brain matter was using almost twice as much energy, evidently due to greater synaptic activity and information processing.” So, how do our ancestors stack up, when compared to us? And is there any evidence of quantum leaps?

How rapidly has intelligence increased over the past few million years?

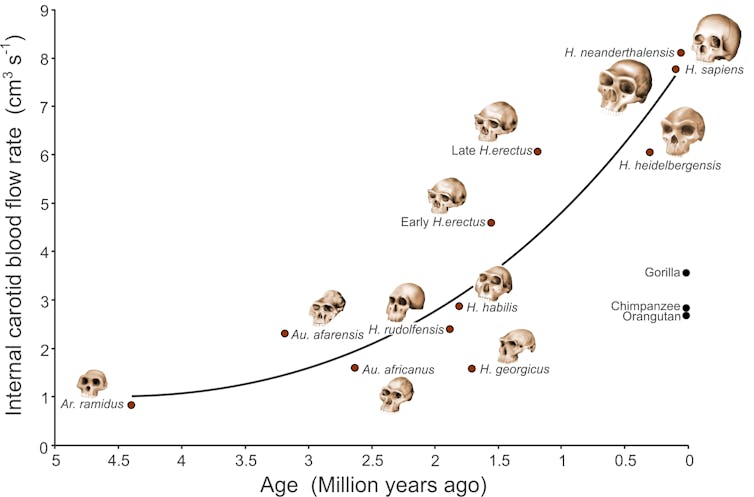

Over time, the brains of our hominin ancestors required more and more energy. This is the best gauge we have of their information-processing capacity. Image courtesy of Professor Roger Seymour (author) and theconversation.com/au.

Seymour’s 2019 study, which was conducted with colleagues at the Evolutionary Studies Institute of the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa and reported in Proceedings of the Royal Society B (13 November 2019, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.2208), found that for 4.4-million-year-old Ardipithecus, the internal carotid artery blood flow was less than 1 cubic centimeter per second, or about one third that of a modern chimpanzee. That suggests it wasn’t too bright. What about Australopithecus? Although Australopithecus had a brain bigger than a chimp’s, and about the size of a gorilla’s (despite having a much lighter body), it turns out that the brain of Australopithecus had only two-thirds the carotid artery blood flow of that of a chimp’s brain, and half the flow of a gorilla’s brain. Seymour concludes that Australopithecus was probably less intelligent than a living chimpanzee or gorilla. How about Homo habilis? Its carotid artery blood flow was about the same as a modern chimpanzee’s, but less than a gorilla’s, at just under 3 cubic centimeters per second. For early Homo erectus, which appeared only 500,000 years after Homo habilis, it was about 4.5 cubic centimeters per second (compared to about 3.5 for a gorilla), while for late Homo erectus, it was about 6. Surprisingly, it was a little less than 6 for Heidelberg man, who’s widely considered to be the next species on the lineage leading to modern man. And for Neanderthal man and Homo sapiens, it was around 8 cubic centimeters per second, suggesting that the Neanderthals’ intelligence roughly matched ours.

Are there any sudden spurts in human intelligence? Probably not

If we plot these figures on a graph (as shown above [image courtesy of Professor Seymour; an even better image of the graph can be found here]), we see that three-million-year-old Australopithecus afarensis (a.k.a. “Lucy”) and Homo erectus both had somewhat higher carotid artery blood flows than would be expected, for the time at which they lived. Was there a sudden spurt in our ancestors’ brainpower when Homo erectus appeared? And what about the surge in carotid artery blood flow from Heidelberg man (6 cubic centimeters per second) to modern man (8 cubic centimeters per second), over the last 300,000 to 400,000 years? What does the evidence indicate?

(i) The arrival of Homo erectus: a great leap forward in human mental capacities?

Above: Model of the face of an adult female Homo erectus.

Image courtesy of Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C. and Wikipedia.

In particular, the jump from Homo habilis to Homo erectus appears fairly steep. It is worth bearing in mind, however, that this “jump” would have occurred over about 400,000 years (which is hardly overnight), as the oldest remains of what’s believed to be Homo habilis (from Lokalalei, West Turkana, Kenya) go back 2.34 million years, while the oldest Homo erectus remains (KNM-ER 2598, from Koobi Fora, Kenya) date back to 1.9 million years.

What’s more, the carotid artery blood flow for Homo habilis turns out to be based on a single specimen, if one examines the original data (see Supplementary Materials) on which the paper was based, which means that the “sudden jump” may well turn out to be a statistical artifact.

Anthropologists are also well-aware that the hominin fossil record is patchy and incomplete, with new species being discovered all the time, which means it is quite possible that some other hominin apart from Homo habilis (perhaps Homo rudolfensis) was ancestral to Homo erectus. [It appears that Homo georgicus is not a likely ancestor: as the graph reveals, its carotid artery blood flow was too small, despite its having a brain size intermediate between Homo habilis and Homo erectus.]

Finally, in a 2016 paper titled, “From Australopithecus to Homo: the transition that wasn’t” (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B vol. 371, issue 1698, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0248), authors William H. Kimbel and Brian Villmoare take aim at the idea that the transition from Australopithecus to Homo was a momentous one, arguing instead that “the expanded brain size, human-like wrist and hand anatomy [97,98], dietary eclecticism [99] and potential tool-making capabilities of ‘generalized’ australopiths root the Homo lineage in ancient hominin adaptive trends, suggesting that the ‘transition’ from Australopithecus to Homo may not have been that much of a transition at all.” In Figure 5 of their article, the authors graph early hominin brain sizes (endocranial volumes, or ECVs) over time, from 3.2 to 1.0 million years ago, for various specimens of Australopithecus (labeled as A), early Homo (labeled H) and Homo erectus (labeled E). From the graph, it can be readily seen that there is a considerable overlap in brain size between Homo erectus and early Homo, shattering the myth of a quantum leap between the two species. Kimbel and Villmoare add that “brain size in early Homo is highly variable—even within fairly narrow time bands—with some early H. erectus crania (e.g. D4500) falling into the Australopithecus range” and conclude that “a major ‘grade-level’ leap in brain size with the advent of H. erectus is probably illusory.”

(ii) Neanderthals and Homo sapiens: in a league of their own?

Above: Reconstruction of a Neanderthal woman (makeup by Morten Jacobsen). Image courtesy of PLOS ONE (Creative Commons Attribution License, 2004), Bacon Cph, Morten Jacobsen and Wikipedia.

There was also a fairly large and rapid increase in carotid artery blood flow from Heidelberg man to his presumed descendants, Neanderthal man and Homo sapiens, from about 6 to 8 cubic centimeters per second. Once again, this increase was not instantaneous, but took place over a period of about 300,000 years. Also, the data relating to Heidelberg man is based on just two specimens; more complete data may reveal a more gradual picture. Moreover, if one examines the original data (see Supplementary Materials) on which the carotid blood flow rates are calculated for different species, it can be seen that the internal carotid artery blood flow rates are significantly smaller for the older specimens of Homo sapiens, suggesting a steady increase over time rather than a sudden leap. Finally, the distinctive globular brain shape that characterizes modern Homo sapiens is now known to have evolved gradually within the Homo sapiens lineage, according to a recent article by Simon Neubauer et al., titled, “The evolution of modern human brain shape” (Science Advances, 24 Jan 2018: Vol. 4, no. 1, eaao5961). This does not square well with the hypothesis of a “magic moment” at which this lineage became truly human.

The clinching evidence for gradualism: the increase in hominin endocranial volume

Finally, a 2018 article titled, Pattern and process in hominin brain size evolution are scale-dependent by Andrew Du et al. (Proceedings of the Royal Society B 285:20172738, http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.2738) provides clinching evidence against any sudden spurts in brain size. In the article, the authors make use of endocranial volume (ECV), which they refer to as “a reliable proxy for brain size in fossils.” Looking at hominins overall, they find that “the dominant signal is consistent with a gradual increase in brain size,” adding that this gradual trend “appears to have been generated primarily by processes operating within hypothesized lineages,” rather than at the time when new species emerged. Du et al. considered various possible models of ECV change over time for hominins, including random walk, gradualism, stasis, punctuated equilibrium, stasis combined with random walk and stasis combined with gradualism. What they found was that gradualism was the best model for explaining the trends observed, by a long shot:

Results from fitting evolutionary models at the clade level show gradualism is by far the best fit for describing hominin ECV change over time (figure 3a and electronic supplementary material, table S3). All mean ECV estimates of the observed time series fall within the 95% probability envelope predicted by the gradualism model (figure 3b and electronic supplementary material figure S1), and model R2 is 0.676 (electronic supplementary material, table S4). Multiple sensitivity analyses demonstrate that support for the gradualism model is robust to bin size or location (electronic supplementary material, figure S5).

The only times when macroevolutionary (as opposed to microevolutionary) processes exhibited a significant influence on trends in the increase in hominin endocranial volume over time were between 2 and 2.3 million years ago (when the larger-brained Homo appeared), between 1.7 and 2 million years ago (when the smaller-brained Australopithecus and Paranthropus disappeared from southern Africa) and between 1.1 and 1.4 million years ago, when Paranthropus (popularly known as “Zinj”) disappeared from east Africa. However, Du et al. found that “within-lineage ECV increase is the primary driver of clade-level change at 1.7–1.4, 1.1–0.8 and 0.5–0.2 Ma [million years ago].”

This finding invites an obvious objection: how could natural selection have possibly favored such a slow rate of brain size (ECV) increase as the one that actually occurred in the hominin line, over millions of years? An increase of 800 cubic centimeters over 3 million years might sound fast, especially when we compare hominins to other lineages of primates, but in reality, it works out at just one extra cubic centimeter of brain matter every 3,750 years! In response, the authors propose that “selection was for larger ECV on average but must have fluctuated and included episodes of stasis and/or drift,” adding that “[a]ll of this occurs on too fine a timescale to be resolved by the current hominin ECV fossil record, resulting in emergent directional trends within lineages.” What needs to be borne in mind, however, is that even punctuated equilibrium models of evolution (which the authors rejected as unnecessary, in order to account for the trends observed) posit changes occurring over tens of thousands of years, rather than overnight. In plain English, what this means is that even if there were any relatively sudden increases in brain size, they would have been fairly modest (say, 20 or 30 cubic centimeters), and they would have taken place over a time span of millennia, at the very least. After that, there would have been long periods when brain size did not increase at all.

Du et al. conclude that the overall trend toward increasing endocranial volume (ECV) within the hominin line “was generated primarily by within-lineage mechanisms that likely involved both directional selection and stasis and/or drift,” as well as “directional speciation producing larger-brained lineages” and “higher extinction rates of smaller-brained lineages.”

So, can we draw a line between humans and non-humans, in the hominin lineage?

In the light of these findings, Christian apologists need to squarely address the question: “Where do you draw the line between true human beings and their bestial forebears?” The fact is, there isn’t a good place to draw one. If you want to say that only Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were truly human, then an awkward consequence follows: their common ancestor, Heidelberg man, wasn’t human, which means that God created two distinct races of intelligent beings – or three if you include Denisovan man, another descendant of Heidelberg man. (Currently, we don’t have any complete skulls of Denisovan man.) Two or three races of intelligent beings? That doesn’t comport with what the Bible teaches or with what the Christian Church has taught, down the ages: only one race of beings (human beings) was made in God’s image (see for instance Genesis 3:20, Malachi 2:10 and Acts 17:26). If you insist that Heidelberg man must have been human as well, then you also have to include late Homo erectus, whose brain had a metabolic rate equal to that of Heidelberg man. But if you are willing to concede that late Homo erectus was truly human, then why not early Homo erectus, who belonged to the same species, after all? However, if you include early Homo erectus within your definition of “truly human,” then you have to address the question: why are you setting the bar so low, by including a species that was not much smarter than a gorilla when it first appeared, used only pebble tools for the first 200,000 years of its existence (from 1.9 to 1.7 million years ago), and only gradually became smarter, over a period of one-and-a-half million years?

In short: the anatomical evidence suggests that while human intelligence evolved relatively rapidly, in geological terms, climbing from the level of a chimp or gorilla to its modern human level in a little over two million years, there is no warrant for supposing that it sprang into existence overnight. The nearest events that we can find to a saltation in the evolution of the human brain are (i) the “sudden” appearance of Homo erectus and (ii) the equally “sudden” evolution of Neanderthal man and Homo sapiens from their presumed ancestor, Heidelberg man, but since the increases in brainpower that occurred here may have taken place over a period as long as 300,000 years, and since there is tentative evidence that they were gradual (at least, in the second case), they provide no support for the Judaeo-Christian hypothesis of a “magic moment” when the human mind, spirit or rational soul was created. The best one can say is that the “magic moment” hypothesis has not been ruled out by the fossil evidence.

================================================================

B. The “Ten Adams” problem

Note: The ten neutral faces shown above were taken from the Princeton Faces database. The software used for face generation was FaceGen 3.1, developed by Todorov et al. 2013, and Todorov & Oosterhof 2011.

But if the evidence from human brain anatomy does nothing to diminish your conviction that there was a “magic moment” at which our ancestors became human, maybe the archaeological evidence of their technical, linguistic, moral and spiritual capacities will change your mind. This brings me to my second reason why scientists reject the view that human intelligence appeared overnight. I’ve decided to call it the “Ten Adams” problem. Please note that the “ten Adams” whom I refer to below are purely hypothetical figures, intended to designate the inventors (whoever they were) of ten cultural breakthroughs that changed our lives as human beings. For the purposes of my argument, it is not necessary to suppose that these figures were particular individuals; the “inventors” of these breakthroughs could well have been entire communities of people.

When we look at the record, we find that there are not one, but ten different points in the past where one might try to draw the line between humans and their sub-human forebears, based on their mental abilities. I’m going to give each of these Adams a special name: first, Acheulean Adam, the maker of hand-axes; second, Fire-controller Adam, who was able to not only make opportunistic use of the power of fire, but also control it; third, Aesthetic Adam, who was capable of fashioning elegantly symmetrical, and finely finished tools; fourth, Geometrical Adam, who carved abstract geometrical patterns on pieces of shell; fifth, Spear-maker Adam, who hunted big game with stone-tipped spears – a feat which required co-operative, strategic planning; sixth, Craftsman Adam, who was capable of fashioning a wide variety of tools, known as Mode III tools, using highly refined techniques; and seventh, Modern or Symbolic Adam, who was capable of abstract thinking, long-range planning and behavioral innovation, and who decorated himself with jewelry. There’s an eighth Adam, too: Linguistic Adam, the first to use human language. And we can also identify a ninth Adam: Ethical Adam, the first hominin to display genuine altruism. Lastly, there’s a tenth Adam: Religious Adam, the first to worship a Reality higher than himself. And what do we find? If we confine ourselves to the first seven Adams, we find that the first Adam (Acheulean Adam) appeared 1.8 million years ago, while the last (Modern or Symbolic Adam) appeared as recently as 130,000 years ago, and certainly no more than 300,000 years ago. It’s harder to fix a date for Linguistic Adam: briefly, it depends on how you define language. On a broad definition, it seems to have appeared half a million years ago; on a narrower definition, it probably appeared between 200,000 and 70,000 years ago. Ethical Adam, if he existed, lived at least half a million years ago, while Religious Adam likely appeared some time after 100,000 years ago, if we define religion as belief in an after-life and/or supernatural beings. So the question is: which of these ten Adams was the first true human? Let’s look at each case in turn.

First, here’s a short summary of my findings, in tabular form:

| The TEN ADAMS | ||

| Which Adam? | Which species? | When? |

| Acheulean Adam, the maker of Acheulean hand-axes | Homo ergaster (Africa), Homo erectus (Eurasia). (Handaxes were later used by Heidelberg man and even early Homo sapiens.) |

1.76 million years ago in Africa; over 350,000 years later in Eurasia. By 1 million years ago, the shape and size of the tools were carefully planned, with a specific goal in mind. [N.B. Recently, a study using brain-imaging techniques has shown that hominins were probably taught how to make Acheulean hand-axes by non-verbal instructions, rather than by using language.] |

| Fire Controller Adam, the first hominin to control fire | Homo ergaster (Africa), Homo erectus (Eurasia). |

1 million years ago (control of fire; opportunistic use of fire goes back 1.5 million years); 800,000 to 400,000 years ago (ability to control fire on a regular and habitual basis; later in Europe). Date unknown for the ability to manufacture fire, but possibly less than 100,000 years ago, as the Neanderthals evidently lacked this capacity. |

Aesthetic Adam, the first to make undeniably aesthetic objects | Late Homo ergaster/erectus. |

750,000-800,000 years ago (first elegantly symmetric handaxes; sporadic); 500,000 years ago (production of aesthetic handaxes on a regular basis). |

| Geometrical Adam, maker of the first geometrical designs | Late Homo erectus |

540,000 years ago (zigzags); 350,000-400,000 years ago (parallel and radiating lines); 290,000 years ago (cupules, or circular cup marks carved in rocks); 70,000-100,000 years ago (cross-hatched designs). |

| Spearmaker Adam, the maker of stone-tipped spears used to hunt big game | Heidelberg man |

500,000 years ago (first stone-tipped spears; wooden spears are at least as old, if not older); 300,000 years ago (projectile stone-tipped spears, which could be thrown); 70,000 years ago (compound adhesives used for hafting stone tips onto a wooden shaft). |

| Craftsman Adam, the maker of Mode III tools requiring highly refined techniques to manufacture |

Heidelberg man (first appearance); Homo sapiens and Neanderthal man (production on a regular basis). |

500,000-615,000 years ago (first appearance; sporadic); 320,000 years ago (production on a regular basis). |

| Modern or Symbolic Adam |

Homo sapiens and Neanderthal man (modern human behavior, broadly defined); Homo sapiens and Neanderthal man (symbolic behavior, in the narrow sense). |

300,000 years ago (modern human behavior – i.e. abstract thinking; planning depth; behavioral, economic and technological innovativeness; and possibly, symbolic cognition); 130,000 years ago (symbolic behavior, in the narrow sense). (Note: the pace of technical and cultural innovation appears to have picked up between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago, probably for demographic reasons: an increase in the population increased the flow of ideas.) |

| Linguistic Adam, the first to use language |

Heidelberg man(?), Homo sapiens and Neanderthal man (language in the broad sense); Homo sapiens (language in the narrow sense). |

500,000 years ago (language in the broad sense: sounds are assigned definite meanings, but words can be combined freely to make an infinite number of possible sentences); 70,000 to 200,000 years ago (language in the narrow sense: hierarchical syntactical structure). |

| Ethical Adam, the first to display genuine altruism and self-sacrifice | Homo ergaster (altruism); late Homo ergaster/erectus or Heidelberg man (self-sacrifice). | Altruism: 1,500,000 years ago (long-term care of seriously ill adults); at least 500,000 years ago (care for children with serious congenital abnormalities). Self-sacrifice for the good of the group: up to 700,000 years ago. |

| Religious Adam, the first to have a belief in supernatural religion | Homo sapiens. |

90,000 to 35,000 years ago (belief in an after-life); 35,000 to 11,000 years ago (worship of gods and goddesses). (N.B. As these ideas and beliefs are found in virtually all human societies, they must presumably go back at least 70,000 years, when the last wave of Homo sapiens left Africa.) |

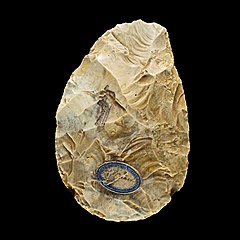

1. Acheulean Adam

|

|

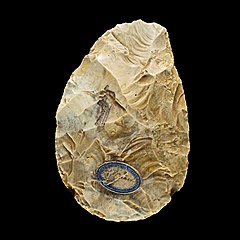

Left: An Acheulean biface from St. Acheul, France. Date: between 500,000 and 300,000 BP. Image courtesy of Félix Régnault, Didier Descouens and Wikipedia.

Right: Drawing of a hand holding a hand-axe. Image courtesy of Locutus Borg, José-Manuel Benito Álvarez and Wikipedia.

| Summary: Until recently, it was widely assumed that Acheulean hand-axes (which humans can learn how to make but chimps cannot) were cultural artifacts. That all changed with the publication of a provocative paper by Raymond Corbey et al. in 2016, arguing that the manufacture of these hand-axes could have been genetically driven, at least in part, and that the hand-axes were no more remarkable than intricately built birds’ nests. Corbey’s paper drew a flurry of indignant responses by scientists working in the field, who argued that there were several features of Acheulean hand-axes which pointed to their being culturally transmitted from generation to generation, and that their makers (or at least, the makers of the later Acheulean hand-axes) had an eye for symmetry, and spend an inordinate amount of time making them – much more than would have been required just to make a tool that did the job of cutting up animal carcasses. That suggests they were interested in perfection for its on sake, which makes them a lot like us. After reviewing the evidence, I find that the cultural hypothesis is likely correct; nevertheless, it is highly doubtful whether “Acheulean Adam,” or the first hominin to make these axes (Homo ergaster, also known as African Homo erectus), was truly human. In the first place, language was not required to teach others how to make the hand-axes; basic teaching would have done the job. Even if language was used for instructive purposes, it was likely very rudimentary. And in the second place, the fact that it took Homo erectus more than one million years to get from making a simple hand-axe to making the first stone-tipped spear suggests to me that he wasn’t “bright,” in the human sense of the word. The pace of technological change seems to have picked up around one million years ago, however, which is roughly when Homo antecessor appeared. Subsequent to this date, Acheulean hand-axes became more refined and (in a few cases) aesthetically pleasing. |

Acheulean tools: Recommended Reading

Coolidge, F. and Wynn, T. (2015). “The Hand-axe Enigma”. Psychology Today. Posted April 2, 2015.

Corbey, R. et al. (2016). “The acheulean handaxe: More like a bird’s song than a beatles’ tune?” Evolutionary Anthropology, Volume 25, Issue 1, pp. 6-19.

dela Torre, I. (2016). “The origins of the Acheulean: past and present perspectives on a major transition in human evolution”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 371(1698): 20150245.

Diez-Martín, F. et al. (2016). The Origin of The Acheulean: The 1.7 Million-Year-Old Site of FLK West, Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania). Scientific Reports volume 5, Article number: 17839.

Gallotti, R. and Mussi, M. (2017). “Two Acheuleans, two humankinds: From 1.5 to 0.85 Ma at Melka Kunture (Upper Awash, Ethiopian highlands)”. Journal of Anthropological Sciences, Vol. 95, 137-181.

Hosfield, R. et al. (2018). “Less of a bird’s song than a hard rock ensemble.” Evolutionary Anthropology. 27 (1), 9-20. ISSN 15206505 doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21551.

Li, X. et al.. (2017). Early Pleistocene occurrence of Acheulian technology in North China. Quaternary Science Reviews 156, 12-22.

Morgan, T. et al. (2015). “Experimental evidence for the co-evolution of hominin tool-making teaching and language”. Nature Communications 6, 6029, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7029.

Putt, S. et al. (2017). “The functional brain networks that underlie Early Stone Age tool manufacture”. Nature Human Behaviour 1(6):0102, DOI: 10.1038/s41562-017-0102.

Semaw, S., Rogers, M. J. and Stout, D. (2009). The Oldowan-Acheulian Transition: Is there a “Developed Oldowan” Artifact Tradition? Chapter from Sourcebook of Paleolithic Transitions: Methods, Theories, and Interpretations. Camps, M. and Chauhan, P. (eds.), Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 173-193.

Shipton, C. et al. (2018). “Were Acheulean Bifaces Deliberately Made Symmetrical?” Cambridge Archaeological Journal, July 2018. DOI: 10.1017/S095977431800032X.

Stout, D. et al. (2015). “Cognitive demands of Lower Palaeolithic toolmaking”. PlosOne 10, e0121804, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121804.

Wynn, T. and Gowlett, J. (2018). “The handaxe reconsidered.” Evolutionary Anthropology. Volume 27, Issue 1, 21-29.

What are Acheulean tools?

Oldowan tools, which first appear in the archaeological record 2.6 million years ago, are typified by pebble “choppers”: crudely worked stone cores made from pebbles that were chipped in two directions, in order to remove flakes and create a sharpened edge suitable for cutting, chopping, and scraping. Acheulean tools, which first appear 1.76 million years ago, are quite different, being distinguished by a preference for large flakes (>10 cm), used as blanks for making large cutting tools (handaxes and cleavers). The best-known Acheulean tools are the highly distinctive handaxes, which were pear shaped, teardrop shaped, or rounded in outline, usually 12–20 cm long and flaked over at least part of the surface of each side (which is why they are commonly described as bifacial). (For more information, readers are invited to view the online article, “Oldowan and Acheulean stone tools” by the Museum of Anthropology, University of Missouri.)

Before making an assessment of “Acheulean Adam,” there are several questions we need to address:

(i) Why can’t Oldowan pebble tools be used to identify the first true human beings, instead of Acheulean hand-axes?

(ii) Can “Acheulean Adam” be equated with any particular species of Homo in the fossil record?

(iii) Do Acheulean hand-axes appear suddenly in the archaeological record, or gradually?

(iv) Were Acheulean hand-axes the product of genetically programmed instincts or cultural transmission?

(v) What kind of minds did Acheulean toolmakers possess, and did they use language?

Answering these questions in detail will require an in-depth review of the current scientific literature on the subject. For the benefit of those readers who would rather skip over the technical details, here are some very brief answers.

(i) Why can’t Oldowan pebble tools be used to identify the first true human beings, instead of Acheulean hand-axes?

Answer: Most scientists don’t think that anything we’d call human intelligence was required to make these tools. Indeed, some experts think the maker of these tools was mentally no more advanced than a chimp, although others believe that he/she was more like one of us. In any case, the intelligence that fashioned these tools still fell far short of our own, as shown by the fact that even bonobos can be taught how to fashion Oldowan-style flakes that can be used for cutting food from small round stones. (That said, the bonobos didn’t do a very good job of making them.) By contrast, no non-human primate has ever manufactured anything like an Acheulean hand-axe.

(ii) Can “Acheulean Adam” be equated with any particular species of Homo in the fossil record?

Answer: Probably not. The first Acheulean hand-axes in Africa were made by Homo ergaster some 1.76 million years ago, while the first hand-axes in Europe and Asia were made by Homo erectus. (Note: Some experts classify both of these species as Homo erectus.) However, Homo erectus lived in Asia for hundreds of thousands of years before it started making Acheulean hand-axes, while Homo ergaster may have lived in Africa for over 100,000 years before starting to create these tools, so it would be unwise to equate either of these species with “Acheulean Adam,” tout simple. Incidentally, Acheulean technology was remarkably long-lived: later Acheulean hand-axes were made by Heidelberg man and even early Homo sapiens, as late as 200,000 years ago.

(iii) Do Acheulean hand-axes appear suddenly in the archaeological record, or gradually?

Answer: The oldest Acheulean hand-axes date back to 1.76 million years ago in eastern Africa, and appear fairly suddenly in the archaeological record, but the record for the next 150,000 years in this region of Africa is patchy. Nevertheless, there are strong theoretical reasons for believing that Acheulean technology must have arisen very suddenly. However, it has been hypothesized that this abrupt appearance could well be due to the confluence, at a particular point in time, of several enabling factors which themselves arose gradually. Also, we do not know whether Acheulean technology was invented once and only once, or whether it was invented independently on multiple occasions.

(iv) Were Acheulean hand-axes the product of genetically programmed instincts or cultural transmission?

Answer: Acheulean tools were most likely the product of cultural transmission. In 2016, Raymond Corbey and his colleagues sparked an academic furore when they argued that the explanation for Acheulean tool-making could be largely (but not entirely) genetic, and that Acheulean hand-axes were no more complex than birds’ nests in their level of intricacy. Several scholars took issue with Corbey’s paper (see here, here and here), pointing out that tool-making is a cultural phenomenon in all tool-making primate species studied to date, and that the makers of Acheulean tools went to extraordinary lengths to make them symmetrical as well as pleasing to the eye. From a strictly functional point of view, this beautification would have been a complete waste of time. Also, Acheulean hand-axes evolved over the course of time: while the earliest ones were fairly crude, those manufactured half a million years ago were much more refined. Indeed, some experts have even proposed that there were two Acheuleans, the second one starting some time after one million years ago. Finally, there were indeed local variations in Acheulean tools. Taken together, these facts suggest that a cultural process was at work, even if the pace of technological change was a glacial one by our standards.

(v) What kind of minds did Acheulean toolmakers possess, and did they use language?

Answer: The makers of Acheulean hand-axes were highly skilled toolmakers. From studies of modern human volunteers, we now know that it would have taken hundreds of hours of practice for them to learn how to make hand-axes and other tools. They also had an eye for symmetry, and after about 750,000 years ago, some of them had an eye for beauty as well, although the production of aesthetic artifacts did not become common until 500,000 years ago.

But did they use language when teaching one another to make these tools? The short answer is that we don’t know for sure, but it probably wasn’t required. Some researchers (Morgan et al., 2015) argue that the use of language would have made it easier for individuals to learn how to make Acheulean tools, but at the same time, they acknowledge that if any language was used in instructing novice tool-makers, it would probably have been pretty rudimentary. As they put it, “simple forms of positive or negative reinforcement, or directing the attention of a learner to specific points” would have been enough; neither a large number of symbols nor a complex system of grammar would have been required. Other researchers (Shelby Putt et al., 2017) argue that language would have actually been a hindrance, as internal verbalization while carrying out instructions would have prevented early hominins from attending to the sound of stone hitting against stone, while tools were being shaped. Instead of possessing linguistic skills, these hominins had highly sophisticated motor, memory and action planning skills, rather like those of a piano player.

At this point, some readers may wish to go on to Section 2, in which I discuss “Fire-controller Adam.” Those who would like to learn more about Acheulean tools are welcome to continue reading, as I proceed to address each of the five issues raised above, in detail.

—————————————————————-

An Archaeological Excursus

(i) Why can’t Oldowan pebble tools be used to identify the first true human beings, instead of Acheulean hand-axes?

RETURN TO MAIN MENU

Oldowan choppers dating to 1.7 million years BP, from Melka Kunture, Ethiopia. Image courtesy of Didier Descouens and Wikipedia.

Some readers may be wondering why I am focusing on Acheulean hand-axes, rather than the earlier (and rather large) Lomekwian anvils, cores, and flakes produced in Kenya 3.3 million years ago (reported in Nature, vol. 521, 21 May 2015, doi:10.1038), or the somewhat more sophisticated Oldowan “pebble tools,” produced by Australopithecus garhi and later, Homo habilis and early Homo erectus, between 2.6 million and 1.3 million years ago. The reason why I am ignoring these tools here is that they are not sufficiently distinctive to be considered as a hallmark of the human race: arguably, chimpanzees could have made them. In 1989, Wynn and McGrew published an influential paper titled, “An ape’s view of the Oldowan” (Man 24(3):383-398), in which they concluded:

“There is nothing about the Oldowan which demands human-like behavior such as language, ritual or shared knowledge of arbitrary design, or other sophisticated material processes. At most one can argue that the Oldowan pushed the limits of ape-grade adaptation; it did not exceed them… In its general features Oldowan culture was ape, not human. Nowhere in this picture need we posit elements such as language, extensive sharing, division of labor, or pair-bonded families, all of which are part of the baggage carried by the term human.” (1989, p. 394)

Wynn and McGrew claimed that only two behavioral patterns distinguished the makers of Oldowan tools from apes: transportation of tools or food for thousands of meters and competing with large carnivores for prey. Even these behaviors they considered to be “still within the ape adaptive grade” and accountable in terms of “differences in habitat.” In a 2011 follow-up paper (Evolutionary Anthropology 20: 181-197), Wynn, Hernandez-Aguilar, Marchant and McGrew reiterate their conclusion, adding: “The Oldowan was not a new adaptive grade, but a variation on an old one… Human-like technical elements made their appearance after the Oldowan… In a techno-behavioral sense, Homo erectus sensu lato [i.e. defined broadly, to include Homo ergaster – VJT] was the intermediate form between ape and human.” The primitive nature of pebble tools becomes especially apparent, when we compare the complexity of the sequential chains of steps (chaines operatoires) required to make Oldowan tools (7 phases, 4 foci, 14 steps, 4 shifts of attention) with the level of behavioral sophistication required by chimpanzees when making tools to extract termites, in order to eat them (7 phases, 4 foci, 9 steps, 4 shifts of attention). As can be seen, the numbers are comparable.

Video above: Chimps using twigs to dig for ants. Authors: Koops K, Schöning C, Isaji M, Hashimoto C. Video courtesy of Wikipedia.

Wynn and McGrew have a valid point. Scientists now know that modern chimpanzees follow an operational sequence when using stone implements to crack nuts, just as the makers of Oldowan pebble tools did. Sometimes they even create sharp-edged flakes in the process, albeit unintentionally. Additionally, chimpanzees in some communities in Guinea, West Africa, will transport stone tools (hammers and anvils) for the purpose of cracking nuts, reuse a stone tool that has been accidentally produced from another stone tool, and follow a sequence of repeated actions leading to the goal of cracking open nuts (for further details, see Susana Carvalho et al., “Chaînes opératoires and resource-exploitation strategies in chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) nut cracking”, Journal of Human Evolution [2008] 55, 148-163).

Even more disconcertingly for “human supremacists,” recent research has shown that capuchin monkeys from Brazil are capable, while bashing rocks into dust, of unintentionally producing sharp-edged stone flakes that resemble ancient stone tools produced by hominins in eastern Africa some two to three million years ago, according to an article in Nature News, 19 October 2016 (“Monkey ‘tools’ raise questions over human archaeological record” by Ewen Callaway).

Other scientists have a different take on the tools produced by our hominin ancestors. In a recent paper titled, “An overview of the cognitive implications of the Oldowan Industrial Complex” (Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 2018, Vol. 53, No. 1, 3–39), Nicholas Toth and Kathy Stick take a more sanguine view of Oldowan tools, concluding that “a variety of archaeological and palaeoneurological evidence indicates that Oldowan hominins represent a stage of technological and cognitive complexity not seen in modern great apes (chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans), but transitional between a modern ape-like cognition and that of later Homo (erectus, heidelbergensis, sapiens).” Toth and Stick acknowledge the impressive tool-making feats of chimpanzees, but point out that in experiments conducted in 2006, when highly intelligent bonobos which had previously been shown how to use stones (made of lava, quartzite and flint) to produce flakes for accessing and cutting food, were then given small round stones (cobbles) to make their own tools from, they managed to produce usable flakes. However, Toth and Stick note that the quality of the flakes they made was poor: “The [2.6-million-year-old Oldowan] Gona cores and flakes were intermediate in skill levels between those of bonobos and modern humans, but much closer to the human sample.” What’s more, the bonobos weren’t as selective about their raw materials as the hominins living at Gona were.

Toth and Stick add that while the fractured debris unintentionally resulting from chimpanzees’ tool-making activities in the wild is reminiscent of prehistoric Oldowan assemblages, “[i]t should be kept in mind… that Oldowan assemblages are, in contrast, clearly the result of the intentional controlled fracture of stone by Oldowan hominins.” They also argue that the rapid increase in brain size that occurred in early Homo must surely mean something: “The difference in brain size between early Homo (650 cm3) and chimpanzees/bonobos and early australopithecines (∼400 cm3) shows an increase in Homo of about 60 percent within one million years. The authors contend that there must have been strong selective forces for this to happen, and that selection was almost certainly involving higher cognitive abilities in foraging, social interaction and communication.” Nevertheless, they candidly acknowledge that not all authorities agree with their upbeat assessment of Oldowan tools, adding that it is their opinion that “the hominins responsible for Oldowan sites herald a new and more complex form of cognition and behaviour”:

“There is clearly a wide variety of opinions regarding the cognitive abilities of early hominins, ranging from the view that hominins were essentially like modern apes to that which sees them as having evolved to a new, more human-like threshold of cognitive abilities.”

In view of the vigorous disagreements among experts in the field regarding the level of cognitive sophistication and behavioral complexity required to manufacture Oldowan tools, it would be highly unwise, in my opinion, to use them as a litmus test of true humanity.

By contrast, no non-human primate has ever created anything like an Acheulean hand-axe, so that makes a better place to commence our investigation of when the first true humans appeared. In a recent groundbreaking study involving brain images taken of human volunteers while learning how to fashion Oldowan and Acheulean tools (“Cognitive demands of Lower Palaeolithic toolmaking”, PlosOne 10, e0121804 (2015) doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121804), Dietrich Stout et al. demonstrated convincingly that the manufacture of Acheulean tools would have required more complex neurophysiological skills than that of Oldowan tools. The study authors collected structural and functional brain imaging data as volunteers made “technical judgments (outcome prediction, strategic appropriateness) about planned actions on partially completed tools” and found that performing these tasks measurably altered neural activity and functional connectivity in a particular region of the brain which is commonly regarded as the “central executive” of working memory, on account of its role in the selection, monitoring and updating of incoming information (the dorsal prefrontal cortex). It was discovered that the magnitude of this alteration correlated with the success of the strategies employed by the novice toolmakers. A correlation was also observed between the frequency of correct strategic judgments and the volunteers’ success in fashioning Acheulean tools; however, no such correlation was found for Oldowan tools, indicating that a lower level of cognitive skills would have been required to manufacture these tools.

—————————————————————-

(ii) Can “Acheulean Adam” be equated with any particular species of Homo in the fossil record?

RETURN TO MAIN MENU

Above: Facial reconstruction of the so-called “Turkana boy”, based on the skeleton of a 1.5 million-year-old Homo ergaster specimen found at Lake Turkana, Kenya. Homo ergaster was the hominin which fashioned the first Acheulean tools, some 1.76 million years ago. Image courtesy of Wolfgang Sauber (photograph), E. Daynes (sculpture) and Wikipedia.

The first hand-axes appear in the archaeological record about 1.76 million years ago. This era in tool-making is called the Acheulean era, so I’ll use the term “Acheulean Adam” to describe the hypothetical first individual or group of people that gained the ability to master this technology. (I should point out here that the term “Acheulean tools” includes not only hand-axes but also picks, cleavers and other large cutting tools, but in what follows, I’ll be focusing on hand-axes.)

The very first Acheulean tools were made by Homo ergaster (known in Europe and Asia as Homo erectus), the first hominin with a recognizably human body and a significantly larger brain than an ape’s. Homo ergaster first appeared in east Africa about 1.9 million years ago; his Asian counterpart, Homo erectus, is believed to have appeared around 1.8 million years ago. It is currently uncertain as to whether Homo ergaster started making Acheulean tools as soon as he first appeared in Africa, or whether he initially continued making and using only Oldowan pebble tools, like those made by Homo habilis, before inventing Acheulean tools. In the judgement of one eminent researcher, Ignacio dela Torre, “there is now evidence that the Acheulean appeared at least 1.75 Ma [million years ago] in the East African Rift Valley, which on an evolutionary scale coincides with the emergence of H. erectus” – a term he uses to include Homo ergaster (“The origins of the Acheulean: past and present perspectives on a major transition in human evolution”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 2016 Jul 5; 371(1698): 20150245).

To be sure, the appearance of Acheulean tools did not immediately kill off Oldowan pebble toolmaking: authors J. A. Catt and M. A. Maslin, in their 2012 article “The Middle Paleolithic” (in Chapter 31, section 31.5.2 of The Geologic Time Scale 2012, Elsevier, ed. Felix M. Gradstein et al.) note that “the Acheulian and Oldowan cultures are found together in East and South Africa between about 1.9 Ma [million years ago] and 1.5 Ma” – a fact which they attribute to “the long overlap in time between late H. habilis and early H. erectus.” Although we have no direct evidence for the hypothesis that early Acheulean tools were only manufactured by Homo erectus, authors Rosalia Gallotti and Margherita Mussi articulate the common view in their article, “Two Acheuleans, two humankinds: From 1.5 to 0.85 Ma at Melka Kunture (Upper Awash, Ethiopian highlands)” (Journal of Anthropological Sciences, Vol. 95 (2017), pp. 137-181), when they state: “Even if multiple hominin genera and species co-existed at the time, there is a general understanding that the new [Acheulean] techno-complex’s only knapper was Homo erectus/ergaster...” (p. 138).

However, F. Diez-Martín et al. question the popular view that Acheulean technology is the signature trait of Homo erectus/ergaster in their article, The Origin of The Acheulean: The 1.7 Million-Year-Old Site of FLK West, Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania) (Nature, Scientific Reports volume 5, Article number: 17839 (2016)):

“The Acheulean technology has been argued to be the hallmark of H. erectus. However, at present this interpretation must be nuanced in the light of hominin types chronologically co-occurring with this and other technologies. First, the presence of H. erectus (or H. erectus-like) fossils antedate the earliest evidence of this technology by at least 200 Ka [200,000 years – VJT] (e.g., the 1.9 Ma KNMER 3228 or OH86)[54] and they occur at a time in which only classical Oldowan is documented. Secondly, there are H. erectus remains directly associated with typologically and technologically Oldowan assemblages (e.g., Dmanisi at 1.7 Ma)[55]. Thirdly, the traditional association of classical Oldowan and H. habilis from Olduvai Bed I has been challenged by the presence of a H. erectus-like hominin (OH 86) at this time[54].”

The authors attribute the relatively sudden appearance of Acheulean tools in the archaeological record to “major climatic changes towards aridity” occurring around 1.7 million years ago in east Africa, which would have favored the appearance of new and more flexible patterns of hominin behavior, and conclude: “The coincidence in time of these climatic changes and the occurrence of the earliest Acheulean would suggest a climatic trigger for this technological innovation and its impact in human evolution.”

Finally, in their article, Early Pleistocene occurrence of Acheulian technology in North China (Quaternary Science Reviews 156 (2017) 12-22), Xingwen Li et al. summarize the evidence for the earliest appearance of Acheulian tools, outside of East Africa:

“Current thinking is that Acheulian technology originated in East Africa (possibly West Turkana, Kenya) at least 1.76 million years ago (Ma) (Lepre et al., 2011), that it became distributed somewhat widely across Africa (e.g., Vaal River Valley and Gona) at ~1.6 Ma (Gibbon et al., 2009; Semaw et al., 2009), and then spread to the Levant at ~1.4 Ma (Bar-Yosef and Goren-Inbar, 1993), South Asia at 1.5-1.1 Ma (Pappu et al., 2011), and Europe at 1.0-0.9 Ma (Scott and Gibert, 2009; Vallverdú et al., 2014) (Fig. 1). The 0.8-0.9 Ma Acheulian stone stools from South and central China (Hou et al., 2000; de Lumley and Li, 2008) (Fig. 1) suggest that Acheulian technology arose in China at least during the terminal Early Pleistocene.”

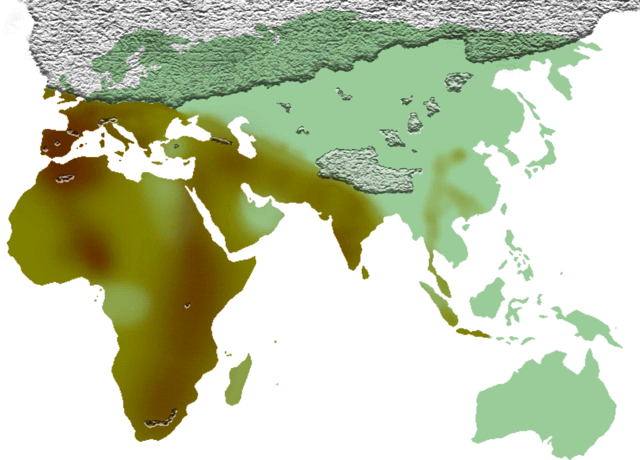

The authors also report the recent discovery of Acheulean tools in North China, dating back to 900,000 years ago, which is about the same time that they appeared in Europe. As early as these dates may be, they are much later than the dates for the first appearance of Homo erectus in Europe and Asia. Homo erectus appears in Dmanisi, Georgia around 1.8 million years ago, in Yuanmou, China, 1.7 million years ago, in Sangiran, on Java, Indonesia, at least 1.66 million years ago, and in Europe at least 1.4 million years ago. Thus in many areas outside Africa, Homo erectus continued using Oldowan pebble tools for several hundred thousand years after he first appeared, and in some parts of east and south-east Asia, Homo erectus seldom or never produced hand-axes. (The Movius line, shown on the map below, indicates the boundary between areas where hand-axes were and were not created by Homo erectus.) What this research suggests is that the very first Homo erectus hominins to have left Africa might not have taken Acheulean culture with them, which would make more sense if they did not yet possess the technology.

Taken together, these findings make it difficult for us to equate “Adam” with the earliest members of Homo ergaster (or Homo erectus), as some creationists and/or Intelligent Design theorists have attempted to do. The picture is much more complicated than that. Although Homo ergaster/erectus was the first hominin to create Acheulean tools, this species didn’t do so right away. Over 100,000 years may have elapsed before Homo ergaster invented this technology, while its appearance in Asia and Europe was much later.

A short note on the Movius line

Map showing the approximate distribution of cultures using Acheulean bifaces during the Middle Pleistocene. In the brownish areas, Homo erectus used Acheulean hand-axes; in the blue-green areas, more primitive Oldowan pebble tools were used. (Australia and New Guinea were uninhabited at the time.) The line dividing the two areas is called the Movius line. In recent years, however, hand-axes have been found about 1,500 kilometers east of the Movius line, in China and South Korea, as well as at locations in Indonesia, causing some authorities to suggest that we should throw out the concept of the Movius line altogether. Other experts continue to defend the validity of the concept. Image courtesy of Locutus Borg, José Manuel Benito Álvarez and Wikipedia.

The concept of the Movius line is somewhat controversial among archaeologists today. Cassandra M. Turcotte, of the Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology, neatly summarizes the reasons that led archaeologist Hallam Movius to draw this boundary back in 1948, in her online article, Stone Tools (2016), written for the Bradshaw Foundation of Paleoanthropology: