In a recent post over at What’s Wrong With the World, Professor Timothy McGrew asks, Did Jesus’ Mother and the Beloved Disciple Stand at the Foot of the Cross? Professor McGrew’s answer is a decisive yes. Readers will recall that last year, in a lengthy review of Michael Alter’s book, The Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry, I summarized the reasons for rejecting the historicity of this episode in John’s Gospel (see here for the arguments I presented). My arguments were taken directly from Alter’s book – a book which Professor McGrew has not deigned to read. Relying instead on the brief summary contained in my post, he roundly declares that he finds these arguments unconvincing and unsubstantiated. Had he consulted Alter’s book, however, he would have found scholarly citations in abundance, as well as the answers to some of the questions he poses in his post.

In this post, I intend to address and rebut Professor McGrew’s objections, and to supply further documentation to back up the claims I made previously. But before I continue, let me begin with the candid admission that I may be wrong, in casting doubt on the historicity of John’s account of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple standing near the foot of the cross. I have done a lot of digging and delving on the subject during the past couple of weeks, and I acknowledge that the issue is not as cut-and-dried as I had previously believed. Nevertheless, if I were a betting man, I’d still bet against the episode’s ever having happened, for reasons I’ll explain below. As I pointed out in my previous reply to McGrew, my chief concern is with those claims which a fair-minded historian would consider probable, when judging matters on purely historical grounds. Hence the title of my last post: Why there probably wasn’t a guard at Jesus’ tomb.

The terms of the debate

The most profound difference between Professor McGrew and myself, however, relates not to the evidence presented, but to the manner in which it should be assessed. In mounting his arguments, Professor McGrew seems to assume that historical investigations of incidents narrated in the Gospels should follow two procedural rules, which I’ll refer to as the Plain Vanilla rule and the Privileged Position rule. The first rule states that the Gospels should be assessed in the same manner as any other historical document – say, the Histories of Tacitus. According to the second rule, the historical narratives contained in the Gospels are to be regarded as true and accurate, unless they can be shown to be highly implausible, on purely historical grounds.

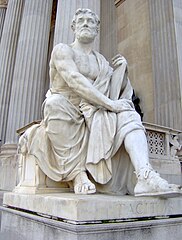

To a layperson, the Plain Vanilla rule may sounds fair and reasonable. Why shouldn’t we apply the same standards of evidence to the Gospels as we do to other documents dating from the time when they were composed? The short answer is that historians are trained to look with a critical eye at claims emanating from sources which are either biased or embellished – and the Gospels appear to be both biased and embellished. As such, they warrant much closer scrutiny than, say, the Histories of Tacitus. (By the way, I’m not saying that the writings of Tacitus are entirely free of bias and exaggeration; what I am saying is that Tacitus at least strives to be scrupulously fair, and generally succeeds: as he writes in his Annals I,1, “my purpose is to relate … without either anger or zeal, motives from which I am far removed.”)

Concerning the Gospels’ bias, there can be no doubt whatsoever: they are written with the avowed intent of showing that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, a real flesh-and-blood individual who was born of a woman, lived among us, was crucified, died and was raised on the third day. That makes them biased against ideologies which teach otherwise, including atheism, polytheistic paganism, Gnosticism and Judaism. And while I cannot prove that the Gospels contain embellishments, I can only say that Matthew’s account of the earthquake at Jesus’ death and of Jewish saints rising from their graves and appearing to people after Jesus had risen certainly appears to be an embellishment, as does Mark’s claim that the curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom at the moment when Jesus breathed his last, not to mention Luke’s affecting narrative of Jesus prophesying Jerusalem’s doom as he was being led away to his death, and John’s description of Jesus being buried with 75 pounds of spices – an amount that was literally fit for a king. In this post, I’ll endeavor to explain why I think John’s story of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple standing at the foot of the Cross is another embellishment.

The problem I have with the Privileged Position rule is that it shifts the onus of proof onto those attacking the veracity of the Gospels. I don’t think that’s at all reasonable, when we’re dealing with documents which are avowedly biased, and which appear to be embellished, as well. Nor do I think it’s reasonable to assume that the Gospel accounts are false until their accuracy can be established by historians and archaeologists, as certain obstinate skeptics do. Instead, what I’m proposing is that when examining the narratives contained within the Gospels, we should ask ourselves: which hypothesis best explains these narratives? Sometimes it will be the hypothesis that the events they describe are actual historical events. And sometimes it will be the hypothesis that the narratives are pious inventions that were created with a theological aim. In any case, inference to the best explanation should always be our guiding principle. Using this principle, the conclusion I have reached is that the best explanation of John’s account of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple standing at the foot of the Cross is that someone made it up, with the aim of demonstrating that Jesus truly suffered physical death (which some Docetic Gnostics at the end of the first century denied: they taught that Jesus’ body was an illusion).

In his post, Professor McGrew contends that to discard facts which do not fit one’s pet theory is to abandon “all proper historical methodology,” and I quite agree. But to cling to the belief that an alleged episode in the past is genuinely historical, when a more parsimonious, non-historical explanation can be found which accounts for the known facts equally well, is no less a betrayal of proper historical methodology, in my view.

A final reason for treating the Gospel accounts with caution is that we don’t know who wrote them. There are excellent reasons why scholars doubt the traditional authors of the Gospels (see also here), which are in all likelihood, neither contemporary nor eyewitness reports, but accounts written at least 35 years after the events they describe. (John’s Gospel was most likely written 50 to 60 years after Jesus’ crucifixion.)

Now, thirty-five years, or even fifty years, might not seem like such a long time. Christian apologists maintain that there would be nothing to prevent the Gospel writers from recording, with a high degree of accuracy, what eyewitnesses remembered about the life and teachings of Jesus. Indeed, there is a common view in conservative theological circles that in people tend to remember things more accurately in oral cultures, where there is little or no writing – a view that Bart Ehrman roundly dismissed as “bogus,” in a 2016 online debate with Mike Licona on the historical reliability of the Gospels (see here for the opening page). Ehrman outlines the reasons for his skepticism:

Since the 1920s cultural anthropologists have studied oral cultures extensively, in a wide range of contexts (from Yugoslavia to Ghana to Rwanda to … many other places). What this scholarship has consistently shown is that our unreflective assumptions about oral cultures are simply not right. When people pass along traditions in such cultures, they think the stories are supposed to change, depending on the context, the audience, the point that the story-teller wants to make, and so on. In those cultures, there is no sense at all that stories should be repeated the same, verbatim. They change all the time, each and every time, always in little ways and quite often in massive ways.

I hope readers can now understand why I don’t take everything I read in John’s Gospel at face value.

A question for Professor McGrew

Having laid out the ground rules for my historical investigation, I’d like to begin by posing a question to Professor McGrew. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that it could be shown that I was right after all about the Gospels containing lots of embellishments, and that the story of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple at the foot of the Cross was fictitious. My question is: would that bother you, and if so, why?

Perhaps Professor McGrew will reply that once we grant that the Gospel writers were prone to piously embellishing their stories, we have no good reason to think that they would not simply create the story of the Resurrection, out of whole cloth. Who is to say that they didn’t just make it up? But the question we need to ask is not whether the evangelists would invent the story of the Resurrection, but whether they actually did. And the available evidence suggests that belief in the Resurrection predates the Gospels by about three decades: the general consensus of scholars is that the Pauline creed of 1 Corinthians 15 was probably composed before 40 A.D. I would add that a flawed source of information about the life of Jesus is a lot better than no source at all. The Gospels can still tell us a lot about Jesus, even if they are biased and heavily embellished (as many biographies are).

Are my views on Mary and the beloved disciple at the foot of the cross considered radical by Biblical scholars?

Professor McGrew chides me for being overly reliant on Biblical scholars having a secularist humanist worldview – in particular, Bart Ehrman and Maurice Casey – in my skeptical critique of John’s account of Mary and the beloved disciple at the foot of the cross. To be sure, I quoted from both of these authors in my review of Michael Alter’s book, The Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry. But the fact of the matter is that there are also many religious scholars who share my skepticism of John’s account.

I’d like to begin by quoting from a book by Fr. Wilfrid J. Harrington, O.P., titled, John: Spiritual Theologian – The Jesus of John (The Columba Press, Dublin; new revised edition, 2007). Fr. Harrington, who has authored numerous books and who is widely regarded as the “dean” of Catholic biblical studies in Ireland, studied theology at the Angelicum in Rome and biblical studies in Jerusalem at the École Biblique. He is currently a professor of scripture at the Dominican House of Studies, Dublin, Ireland, and visiting lecturer at the Church of Ireland Theological College, Dublin. So let’s see what this esteemed Dominican priest and Biblical scholar has to say about the historicity of John’s account of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple standing by the foot of the cross:

In [John] 19:25-27 John has by the Cross the Mother of Jesus and the Beloved Disciple. The mother of Jesus was the first person in the story to trust unconditionally in the word of Jesus (2:3-5). Now, lifted up on the Cross, Jesus bids her accept the Beloved Disciple as her son. He bids that model disciple accept the mother of Jesus as his mother…

The scene is surely symbolic as a new relationship is set up between the mother and the disciple. The disciple ‘took her to his own.’ The model disciple obeys unquestioningly the word of Jesus. Mark tells us that at the crucifixion, ‘there were also women looking on from a distance’ (Mk 15:40; see Mt 27:55, Lk 23:49) and makes no mention of the mother or of any male disciple. It is wholly unlikely that women and a follower of Jesus would have been permitted to stand at the very place of execution. Here the theological creativity of John is very much in evidence. (pp. 89-90)

In plain English, what Fr. Harrington is saying is that John made the episode up, for theological reasons. The foregoing citation from Fr. Harrington (who is now 92) suffices to show that my skepticism regarding the historicity of John’s account is hardly novel or radical: it is endorsed by a 92-year-old Catholic Biblical scholar – and a Dominican priest at that.

Fr. Harrington is but one of many religious scholars who have questioned John’s account of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple standing at the foot of the Cross. On pages 170-171 of his book, The Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry (Xlibris, 2015, paperback), Michael Alter lists several other authors who reject the historicity of the account, including Ernest John Tinsley (Bishop of Bristol from 1976 to 1985), Mary R. Thompson (a Catholic nun) and Charles Kingsley Barrett, a Methodist minister who has been described as standing alongside C. H. Dodd as “the greatest British New Testament scholar of the 20th century” (see here) and as “the greatest UK commentator on New Testament writings since J. B. Lightfoot” (see here). Another scholar quoted by Alter (on page 172) who is skeptical of John’s account is Rudolf Schnackenburg, a German Catholic priest and New Testament scholar whom Pope Benedict XVI, in his book Jesus of Nazareth, referred to as “probably the most significant German-speaking Catholic exegete of the second half of the twentieth century.”

Here’s what Tinsley has to say on the story of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple standing near the Cross in his work, The Gospel According to Luke (1965, Cambridge University Press, p. 204, emphasis mine):

The Romans did not permit bystanders at the actual place of execution. John’s account is influenced by his symbolic aim. The mother (old Israel) is handed over to the care of the ‘beloved disciple’ (who represents the new Israel of the Christian Church).

And here’s Fr. Schnackenburg, writing in The Gospel According to St. John (1982, New York: Crossroads, p. 277, emphasis mine):

They are standing ‘by the cross’, apparently near Jesus. Whether this is historically probable, since the guard would scarcely allow spectators to approach so close does not worry the evangelist; his concern is with the deeper meaning of the scene.

Later on (1982, p. 281), Fr. Schnackenburg hedges his bets on the historicity of the scene depicted by John; nevertheless, the above citation demonstrates that he is well aware of the difficulties that it poses for historians.

Scholarly bluff?

Not content with belittling my credibility on historical matters (which he is perfectly entitled to do), Professor McGrew goes on to question the credibility of two highly acclaimed Biblical scholars, despite the fact that he possesses no expertise whatsoever in their field. Specifically, McGrew accuses Bart Ehrman and Maurice Casey of a scholarly bluff in making the claim that Roman soldiers would have prevented bystanders (and especially family members and male disciples) from approaching Jesus on the Cross. Actually, Ehrman does not make this claim in the post I cited, so it is rather unfair of McGrew to criticize him for failing to document it. Here are the relevant passages in McGrew’s post, where he calls the Biblical scholars’ bluff:

There is no reference — in Torley’s piece, in Ehrman’s blog post, or in Casey’s entire book — to even one occasion where anyone not already in trouble with the law is arrested, turned away, or even verbally warned for standing too near to the foot of a cross at a public crucifixion in a time of peace…

In short, the objection to the presence of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple near the cross during the crucifixion is entirely bereft of evidential support. When the supposed exclusion of non-criminal bystanders from the scene of crucifixion, even very close up, is advanced as if it were an established fact by those who should know better, it is nothing more than a scholarly bluff.

“Nothing more than a scholarly bluff”? Them’s fighting words. It is a pity that Casey does not provide explicit documentation in his book for his claim that Roman soldiers would have prevented bystanders from approaching Jesus on the Cross, but as we have seen above, several other Biblical scholars who are devout Christians (e.g. Harrington, Tinsley, Thompson, Barrett, Schnackenburg) have said exactly the same thing. If Professor McGrew wishes to accuse all these scholars of bluffing, he is welcome to do so, but if he does, most of his readers will rightly judge him impertinent.

Had Professor McGrew bothered to consult page 171 of Michael Alter’s book, The Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry (Xlibris, 2015, paperback), he would have found some of the documentation he requested. When discussing the work of C. K. Barrett, he writes:

Furthermore, he [Barrrett] cites Josephus (Vita, 420 f.) who recorded that with special permission he was able to release three friends who were crucified. One friend actually survived. This incident is significant because it demonstrates that permission would be needed to approach the crosses.

Professor McGrew wanted documentation. Here it is, in Alter’s book. But wait, there’s more! Most readers will have heard of the late Fr. Raymond Brown (1928-1998), a leading Catholic Biblical scholar who was acclaimed as “the premier Johannine scholar in the English-speaking world,” and who authored the highly acclaimed work, The Death of the Messiah (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1994). In Volume II, Fr. Brown discusses the historicity of John’s and Mark’s differing accounts of the location of the women at Jesus’ crucifixion, setting forth his reasons for treating John’s account with great caution, and documenting his arguments with historical evidence to support his assertions:

…[T]here is no hint in the Synoptics that would support the Johannine picture of Jesus’ mother as present at the cross. Luke, who will later mention her presence in Jerusalem before Pentecost (Acts 1:14) would have been likely to name her among the Galilean women if he knew that she was present at the crucifixion. (p. 1018)

Nothing in the other Gospels would support the presence of Jesus’ mother at Golgotha, but there is some evidence that disciples who were not members of the Twelve were involved in the PN [Passion Narrative]. As for Roman custom, some appeal to later rabbinic evidence that often the crucified was surrounded by relatives and friends (and enemies) during the long hours of agony. Yet in the reign of terror that followed the fall of Sejanus in AD 31, “The relatives [of those condemned to death] were forbidden to go into mourning” (Suetonius, Tiberius 61.2; see also Tacitus, Annals 6.19). Under various emperors of this period, relatives were not allowed to approach the corpse of their crucified one (#46 below). Thus we cannot be sure that Roman soldiers would have permitted the contact with Jesus described in Jn. 19:25-27 (p. 1029)

Professor McGrew requested documentation, and Fr. Brown has supplied it.I hope Professor McGrew will now withdraw his accusation of “scholarly bluff” and acknowledge that he spoke too soon.

In a later passage, Fr. Brown contrasts John’s account of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple standing near the foot of the cross, which he says runs contrary to contemporary Roman practice, with Mark’s account of a group of women watching the Crucifixion from afar, which Brown regards as highly plausible:

3. Followers of Jesus. John alone places those near the cross of Jesus before his death, and in #41 (ANALYSIS A) I warned that it would be unusual for the Romans to permit family and sympathizers such proximity. As for their presence at a distance after the death (Synoptics), at certain periods of heightened Roman fears of conspiracy or of recurrent revolts it would have been unwise to signal sympathy with the convicted. But as I pointed out in #31 (A and B), there is no record of organized revolts in Judea during the prefecture of Pilate; he was not a ferociously cruel governor (pace Philo); nor is there real evidence that there were plans to arrest Jesus’ followers as if he were the leader of a dangerous movement. Consequently there is nothing implausible in the Synoptic picture of the women followers (Galileans, perhaps not even known in Jerusalem) observing from a distance, not expressing in any way their attitude toward the crucifixion. (p. 1194).

Brown then goes on to suggest (1994, p. 1195) that the author of John’s Gospel drew from a pre-existing tradition about Galilean women who observed the crucifixion from afar, but deliberately “moved them close to the cross” in order to combine them with his story of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple conversing with Jesus near the foot of the Cross. Evidently Brown thinks the author of John’s Gospel was fully capable of taking literary liberties.

The question Professor McGrew never asked

In my lengthy review of Michael Alter’s book, The Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry, I raised the issue of the beloved disciple’s identity – a question which I regarded as of central importance in establishing whether John’s Gospel is historically reliable:

I would argue that until we can settle the question of the Beloved disciple’s identity, we are unable to settle the question of the Fourth Gospel’s reliability.

In my post, I noted difficulties with the traditional view that the beloved disciple is the apostle John. Strangely, however, nowhere in his post does Professor McGrew address this question of the beloved disciple’s identity. So I would like to ask Professor McGrew: why does he regard it as irrelevant to the historical credibility of John’s Gospel, given that the beloved disciple is cited several times as an eyewitness of the events described therein? Or if he does regard it as relevant, who does he identify the beloved disciple with?

Why harmonizers’ arguments fail

In all fairness, I should point out that Fr. Harrington’s skeptical position regarding the story of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple near the foot of the Cross is by no means a unanimous one among scholars. Professor Professor Eckhard J. Schnabel is a German evangelical theologian and the author of numerous scholarly books, Bible commentaries and specialist articles. In his latest work, Jesus in Jerusalem: The Last Days (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018), he defends the historicity of John’s account and attempts to harmonize it with the Synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew and Luke), proposing that whereas John describes the presence of the women at the beginning of Jesus’ crucifixion, “when Jesus was still alive and when it is quite plausible that some of the women … stood closer to the three crosses,” the other evangelists describe the scene after Jesus had died, “when it would have made sense for the women to move further away” (p. 321). In a comment on Professor Tim McGrew’s post, his wife, Dr. Lydia McGrew, makes a similar point, in her characteristically vigorous language:

For goodness’ sake. He’s on the cross for six hours. Nobody ever moves around during that time??? This is “speculative”??? You’ve got to be kidding. People move around *constantly* in real life. Not to mention the fact that “the women” could mean various women, not all the same women. Sometimes, I swear, the people who make such objections don’t seem to live in the actual world. They live in a world of statues or something.

I was extremely surprised to find that Professor McGrew, in his discussion of whether Jesus was actually convicted on a charge of high treason (as many scholars contend) never even mentions John Granger Cook’s article, ‘Crucifixion and Burial’ (New Testament Studies, 57 (2011), 193–213). When I wrote my review of Alter’s book, The Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry, I was not aware of Cook’s article, but its relevance to the present discussion is obvious. Briefly, Cook contends that Jesus was probably convicted not on a charge of high treason, but on a lesser charge of sedition. (Fr. Raymond Brown is of the contrary view, citing John 19:12 in support of his opinion, but Cook considers this verse less than decisive.) Although Cook does not mention John’s account of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple at the foot of the Cross, his claim, if correct, would dramatically weaken the force of the argument that Jesus’ family members and male disciples would not have been allowed near the Cross.

Not being a Biblical scholar, I would hesitate to venture an opinion on this issue. However, the repeated (and often mocking) references to Jesus as the “king of the Jews” in the Gospel Passion Narratives make me doubtful that the Romans would have regarded Jesus’ claims as amounting to nothing more than sedition. Still, I may well be mistaken. Even if I am, however, there are still weighty reasons for treating John’s account of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple at the foot of the Cross with skepticism, as I’ll argue below.

Another commenter, a former military infantry officer and policeman named Rad Miksa, also weighed in on the controversy, arguing (see here, here and here) that we cannot be certain that the Roman soldiers would have followed their orders to keep away friends and relatives to the letter:

The problem with this objection is that even if it is true, it still fallaciously treats soldiers like automatons; as if they merely follow orders in an exact and literal way without any thought or initiative of their own.

On the basis of his experience as a policeman, Miksa argued that if the beloved disciple were a small and physically unimpressive man, who politely asked the soldiers for a brief word with Jesus, it is quite likely that they would have relented and granted his request.

Miksa’s testimony as an officer of the law merits serious consideration. Critical to his case, however, is the claim that the beloved disciple’s presence by the Cross was a very brief one: “So the mother and disciple could have been close to the cross at some point for a short period of time, then moved to being a distance away.” The problem I have with that view is that John’s Gospel appears to suggest otherwise. Some time later, after Jesus has died and given up his spirit, Roman soldiers approach the Cross, to break the legs of the crucified victims. Finding Jesus dead, one of them decides to pierce his side with a spear instead, and immediately, blood and water gush out. John 19:35 notes: “The man who saw it has given testimony, and his testimony is true. He knows that he tells the truth, and he testifies so that you also may believe.” That sounds a lot like the beloved disciple – especially when we compare this passage with what John 21:24 declares about the beloved disciple: “This is the disciple who testifies to these things and who wrote them down. We know that his testimony is true.”

So here’s the difficulty: John 19 appears to imply that the beloved disciple was hanging around the Cross for some length of time. (As Alter points out in his book, he must have been standing very close to the Cross, in order to visually distinguish the blood from the “water” issuing from Jesus’ side. Remember: Jesus had already been heavily scourged, before being crucified, so his body would have been covered with blood, making it hard to see the “water.”) But while it is quite possible that Roman soldiers may have allowed Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple to have a brief conversation with Jesus, it is most unlikely that they would have allowed them to remain standing around the Cross for several hours.

The elephant in front of the Cross: why arguments from silence sometimes work

And now we come to what I will call the elephant in front of the Cross. Who is the elephant? Jesus’ mother. Please allow me to explain.

Suppose that one of the evangelists had carefully recorded the presence of an elephant standing in front of the Cross, while Jesus was hanging there, but none of the other evangelists had even mentioned such a spectacle. How would a rational historian treat the account of the elephant? He or she would rightly disregard it as an embellishment. Why? Because the presence of the elephant would have been too big a fact for the other evangelists to ignore.

The presence of Jesus’ mother near the foot of the Cross is recorded in John’s Gospel, where she is named along with a couple of other women, but the other three Gospels, two of which also list the women present at Jesus’ crucifixion (but watching from a distance) never even mention Jesus’ mother. Now, it is quite possible that Mark, who portrays Jesus’ family (including his mother) as being convinced that he was mad, might have ignored this fact. But in Matthew and Luke’s Gospels, Mary is the virgin mother of the Messiah. Luke’s account of Jesus’ birth is especially reverential in its treatment of the Virgin Mary: as Catholic commentators have pointed out, he even likens her to the Ark of the Covenant in the Old Testament: just as the Ark of the Old Covenant was the dwelling place of the Lord, so in Luke’s Gospel, Mary’s body was the new dwelling place of the Lord, in the months leading up to the birth of Jesus. As if that were not enough, Luke also records the presence of the Virgin Mary with the apostles, the other women and Jesus’ brothers, shortly after Jesus’ Ascension into Heaven (Acts 1:14). I’d now like to return to a passage I cited above, from Fr. Raymond Brown’s The Death of the Messiah (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1994, Volume 2):

…[T]here is no hint in the Synoptics that would support the Johannine picture of Jesus’ mother as present at the cross. Luke, who will later mention her presence in Jerusalem before Pentecost (Acts 1:14) would have been likely to name her among the Galilean women if he knew that she was present at the crucifixion. (p. 1018)

Brown makes a valid point here. If Jesus’ mother was present near the foot of the Cross, quite possibly for several hours (as she would have been if she were accompanying the beloved disciple, whom Jesus had just given to her as her adoptive son, in John 19:26-27 – “Woman, behold your son”), then why does Luke, who reveres her so greatly, never even mention this singular fact?

Professor McGrew is dismissive of what he refers to as “Casey’s argument from silence, writing that it is “as bad as such arguments generally are.” But as my illustration of the elephant shows, there are times when the argument from silence works, and this is one of them. In order to account for the absence of any mention of Jesus’ mother in the Synoptic Passion Narratives (Matthew, Mark and especially Luke, who has the highest regard for the Virgin Mary), Professor McGrew would presumably fall back on the suggestion made by commenter Rad Miksa, that maybe the other witnesses to the Crucifixion (such as John Mark) weren’t paying attention when Jesus’ mother dropped by for a brief chat with her dying son. I can only say that this suggestion strikes me as very ad hoc – especially in light of the fact that the beloved disciple, who was with her, appears to have stayed by the Cross for a much longer period. In other words, Professor McGrew can rescue John’s Gospel only by employing a strategy of special pleading. I will not say he is wrong, but I will say that I think he is probably mistaken, and that a fair-minded historian would treat John’s depiction of Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple at the foot of the Cross as a claim which is open to doubt.

Finally, it should be noted that John’s account of Jesus’ death betrays obvious theological motivations. John is anxious to show that Jesus truly died and that he bled like a man when he did (contrary to claims made by Docetist heretics that his body was an illusion) and that he was the Lamb of God, who died on the very day when the Paschal lambs were being sacrificed, and whose bones (like those of the Paschal lamb) were never broken. To bolster his claim,John needs a credible witness (the beloved disciple) who was standing close enough to the Cross to observe all these things. Has John embellished his account? It would appear that he has.For my part, I am happy to grant that the beloved disciple may well have witnessed Jesus’ death, but I think it more likely that he did so from a distance.

But enough of me. What do readers think? Over to you.

fifth,

You don’t know that it’s revelation from God. Even you have admitted that you can be mistaken about a purported revelation.

So yes, it is much smarter to test the Bible instead of assuming that it’s from God.

Of course that is not to say that God can’t reveal his Gospel to someone without that person having heard or read about it beforehand

quote:

For I would have you know, brothers, that the gospel that was preached by me is not man’s gospel. For I did not receive it from any man, nor was I taught it, but I received it through a revelation of Jesus Christ.

(Gal 1:11-12)

end quote:

peace

I agree. I think implausibility is a strong reason to question historical claims where there is no corroborating evidence.

Certainty is not a prerequisite to knowledge.

I don’t assume it’s from God.

God tells me it’s from him.

peace

That is the point, Vincent has corroborating evidence that the Bible is from God.

He is purposely ignoring this evidence in order to appear to be fair minded and impartial to unbelievers who don’t have access to that evidence.

I think that is foolish

peace

fifthmonarchyman,

It would be like Attorney General Barr pretending that he has not read the Muller Report just in order to win favor and seem impartial to those leftwing pundits who don’t know what it says.

peace

P.S And doing it here given the moderation policy is like doing it on MSNBC.

I wrote:

Wake me up when you’ve found someone who believes in the Christian God without having heard or read about him beforehand.

I’m not asking God to do anything, I am asking you to show that it is possible to believe in, or even know about, the Christian God without reading or hearing about him somewhere first.

It all starts there, each and every time: somebody hears or reads about God and then starts to take an interest (or not, as the case may be). Nobody has innate knowledge about the Christian God. All such belief starts with information acquired from the outside world. And as per my original post, the provenance of that information is pretty much lost in the mists of time. If you believe it, it is not because the strength of the historical evidence.

I already did that.

Did you not read the claim from Paul?

Everyone has knowledge about the Christian God because God has revealed himself to everyone (Romans 1)

We just don’t have innate knowledge of the Gospel

Christianity is a revealed religion that is why it’s called the Gospel (ie good news)

We shouldn’t believe anything whatsoever based only on the strength of historical evidence alone.

There are simply to many valid reasons to doubt the veracity of our senses and reason to place that much blind faith in them.

peace

fifthmonarchyman,

If we are to believe the Bible, Paul had very much already heard about Christianity before his conversion. He was on a mission to arrest the followers of Jesus!

We need to separate knowledge about Christianity from saving knowledge of the Gospel.

I’d say everyone today has knowledge of Christianity.

quote:

the gospel that you heard, which has been proclaimed in all creation under heaven, and of which I, Paul, became a minister.

(Col 1:23a)

end quote:

But few have a saving knowledge of the Gospel Paul certainly did not until Jesus revealed himself to him.

I’m exactly not sure what you are getting at.

Could you elaborate on why you think the fact that Christianity is a revealed religion is a problem.

peace

faded_Glory,

I think this might help you

peace

Marketing.

You’d say, or Paul would? (Or do you say so because you hear that Paul did?) You can’t even distinguish your own views anymore, I don’t think–God being truth and all that.

I’d say it’s because God said it and I believe him.

I hope that as I grow to know God better my views will increasingly be his views. Since God’s opinions are infinitely superior by definition it’s only logical that I try and emulate them as much as possible.

All true and worthwhile science and philosophy is just thinking God’s thoughts after him

He must increase, but I must decrease.

(Joh 3:30)

peace

Hi fifthmonarchyman,

Sorry for not answering your questions sooner. Anyway, here goes.

Of course. Even if I’d never heard of the Bible, I’d believe that. I happen to think that natural knowledge (without the aid of supernatural revelation) can take us to the conclusion that there must be an all-perfect God, Who is all-knowing and all-loving. (Please note that I speak of knowledge, rather than proof. I think natural theology can take us to God, but I don’t think it can rigorously demonstrate God.) And if God is all-knowing, then He understands that I’m a human being possessing reason and free will, seeking to know whence I came, what I am and whither I will go – in other words, one of the few creatures capable of knowing its Creator. If God didn’t love each and every human being personally, then He’d be deficient – in which case, He wouldn’t be God.

I’ll respond by quoting a passage attributed (incorrectly, as it turns out) to John Maynard Keynes, but actually uttered in 1970 by Dr. Paul Samuelson: “Well, when events change, I change my mind. What do you do?”

Of course. But God did not write the Bible, so the analogy doesn’t hold. Many people believe that God inspired the Bible, but it was humans who wrote it. And frankly, I’m not at all sure I understand what inspiration means.

Reason tells us that if God is all-perfect, then He cannot lie. You seem to believe that God talks to you through the Bible. I’m happy to grant that He does, but I don’t think the Bible is simply a record of God talking to us.

If you want to know why I have doubts on that score, then have a look at the following 2014 post by Professor Tim McGrew’s wife, Dr. Lydia McGrew:

No magic bullet–Copan’s insufficient answer to the slaughter of the Canaanites.

Please note that the McGrews are not inerrantists.

So much is obvious. Why don’t you read through the thread again and try to follow my argument? You’ve dragged it straight into the weeds.

I agree, My question was not about God in the abstract. I’m asking if you know that he loves you personally and is trustworthy.

Just because God is All loving does not mean he loves everything. God does not love lots of things as I’m sure you agree.

Do you think he loves you in exactly the same way that he loves Judas or Hitler or the Devil? Does he love you in exactly the same manner today as he loves someone who would crucify his Son in a heartbeat and spit in his face for all eternity?

What exactly do you make of this passage?

All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work.

(2Ti 3:16-17)

Inerrantisit is a loosey goosey word. I’m not an Inerrantisit as it’s defined by a lot of folks.

I do believe that the Bible is God’s word and that God is trustworthy. Do you disagree with me?

peace

Why don’t you go to back to sleep until you discover someone who trusts God with out knowing anything of substance about him. 😉

I read your comments and you seem to be claiming that saving faith requires some prior knowledge. That idea deserves the Nobel prize for obviousness.

What I don’t understand is why you think it’s a problem for Christianity.

peace

Perhaps you could write an OP to lay out your reasoning to think this? I for one would find it a lot more interesting than fretting about whether there really was a woman named Mary standing before a cross with her son (Son?) on it.

For extra points you could perhaps also explain why Christianity in particular would follow from that belief?

I also would very much like to see someone make that case

peace

If I understand you correctly you believe that God loves everyone personally but try as he might he is unable to ever save the majority of those he loves in that personal way.

Don’t you think that is a deficiency?

peace

fifthmonarchyman,

One more try:

What is it that leads some people to file the Iliad in the category of ‘myth with perhaps some kernel of historical truth in it’, but the Bible in the box of ‘largely true with perhaps some embellishments’?

The salient point is that both texts are much alike when it comes to our knowledge of their provenance. I simply don’t understand why they get such a diverse treatment. Would anyone really produce lengthy writings to discuss the veracity of Achilles dragging the body of Hector behind his chariot? Unlikely, no? Then why this obsession with biblical details like guards standing at tombs and women standing at crosses? Apparently some people see a massive difference. I simply don’t, and I’m curious to understand why others do.

Because they know that the Bible is God’s word and they trust him to be truthful. The Iliad on the other hand does not effect folks in the same way

It’s pretty simple.I’m not sure why you are having difficulty understanding

peace

Because they know, or because they think they know? How could they tell the difference?

VJ,

I don’t have anything personal against the McGrew’s, but I thought some of their justification for the historicity of the gospels was weak.

Thanks for posting on these topics.

Thanks by the way for pointing out the McGrew’s aren’t inerantists.

Again, no personal slight intended to the McGrews. They seem like nice people. I feel bad having to take issue with some of what they say.

because they know.

Revelation,

God reveals to them that the Bible is the word of God.

It’s called the internal witness of the Holy Spirit and this special revelation conforms exactly to other more general revelation accessed through our senses and reason.

peace

fifthmonarchyman,

And…. we’re back on the merry-go-round. Have fun and don’t fall off, something bad might happen to you!

Only if it is God’s Will.

What merry-go-round? There is no need to go around in circles. You asked a simple question and I gave you a simple but satisfying answer. The answer stands on it’s own.

I am always amazed that when people are presented with an answer that they don’t like they somehow think that something is amiss.

If you can’t find anything incoherent or illogical in the answer why not just accept it?

You asked about the difference between the Bible and the Iliad, the simple answer is that one is God’s word and the other is just an interesting ancient tale.

peace

Wonder why there are so many different interpretations of God’s Words if God reveals stuff so you know it is true? Is somebody mistaken about revelation?

I don’t think there are that many interpretations especially considering that there are over 7 billion people in the world and thousands of different cultures and divisions among cultures. Humans don’t seem to agree on most anything at all. I’m not sure why you think Biblical interpretations should be any different.

Also the number and range of interpretations go down exponentially if we exclude interpretations from people who have authorities that are equal or greater than God’s word.

The fact is that there is a vast chasm between revelation and it’s interpretation and we humans are natural born lawyers. The oldest and easiest trick in the book for a kid is to ask sheepishly “did Dad really say?” When he knows perfectly well what Dad said. Every kid is a born expert at that one.

Mistaken in what way exactly? Human’s can’t help but be mistaken about some things it’s part of being finite creatures. And we Humans have the additional problem in that we are born rebels. That is what revelation and the Holy Spirit are for.

God promised to guide his disciples into the unity of truth through the Spirit and his word but he did not promise that it would be immediate or with out struggle and hard work. If it was easy for us we would forget that we owed everything we have to God’s grace.

Also keep in mind that he did not promise that he would guide those those who were not really willing to do what he says.

The important thing to remember is if it was not for our little divisions we Christians would not get to experience the contrasting joy that comes from our eventual unification in Christ’s truth.

One of the coolest things I’ve gotten to experience is when Christians begin with different interpretations of some bibical text and after some prayerful discussion come to consensus.

peace

Right. They are just the same.

Revelation is not magic it’s just communication. What makes revelation from God special is only it’s source. It’s destination is still human.

peace

Be warned, Vince. This is a religious test.

Nothing unless unless Divine Revelation was superior in some way to non-divine revelation as justification for belief.

Could you elaborate about authorities?

“faded_Glory: Because they know, or because they think they know?

Fifth: because they know.”

If there is a chasm, it seem unlikely that all of them know. After all if something is not completely true ,it is false.

Right, we learn by our experience ,fallible senses, and introspection. That is why there is doubt and disagreements.

With Divine Revelation , it seems like there is no doubt and disagreements. If an omnipotent being can make us know stuff, why can’t He make us know the same stuff that is the correct interpretation of the Revelation? That seems like the useful part of knowledge.

It is superior to non-divine revelation because God being omnipotent can reveal stuff so that I can know.

The difference is in the source not in the revelation it’s self.

Suppose I declair that interpretations of Scripture are authoritative only if they agree with a particular individual,institution or human document. Then I have made the particular individual, institution or human document an equal or greater authority than God’s word.

The more such conflicting authorities there are in the world the more difficult it will be for everyone to come to a consensus on the meaning of a particular text.

who is all? Not every one know’s the Bible is God’s word

quote:

My sheep hear my voice, and I know them, and they follow me.

(Joh 10:27)

end quote:

All his sheep might hear his voice in Scripture and therefore know it is true but still not know exactly how to interpret it. We are only human after all.

Speak for yourself I learn by God leading me to the truth. Sometimes he uses my senses etc. to do this.

Since you don’t have the luxury of an omniscient and omnipotent guide how do you know you are actually learning anything and not just imagining that you are?

He could do that but he certainly does not have to.

God’s is not in anyway bound by what newton thinks is useful.

peace

Maybe you are mistaken about that.

He promised that through revelations to humans who can be mistaken and misinterprete things. You claim to know those things.

So one must have obedience to something first in order to know what that something is? No offense but that seems like a catch 22. And the reason for that ia choice or that even an omnipotent God cannot make you know stuff unless you are willing to do what He says?

So in the meantime of this plane , the little divisions mean ,for some, Divine Revelation leads to false knowledge.

I trust you,I expect it is, Funny that an omnipotent being could not or choose not to accomplish that in the first place.

peace

Mistaken about what? Humans can be mistaken about almost anything.

I’m definitely not mistaken about that. 😉

What things? I know lots of things and so do you.

We know things only because God chooses to reveal things to us.

You claim that you don’t know that. 😉

For some who?

Are you speaking of yourself here or those who recognize God’s voice?

If you actually recognize God’s voice you certainly know that is was not his voice that lead you into any false knowledge you may have

How so? You seem to have a jacked up notion about God.

Why would God not want his sheep to experience an ever increasing knowledge of him?

peace

Not at all. It’s just that obedience and correct interpertation are often found together.

No

It’s just that knowing stuff and doing what he says is often a package deal.

God is not only interested in showing his church stuff he is also in the business of making us better people.

peace

Vincent:

fifth:

walto:

Heh. Fifth as Inquisitor.

Perhaps fifth should show Vincent the instruments of torture when asking these questions.

Here are more of fifth’s religious tests:

And:

And:

Be very careful, Vincent. Fifth is watching you.

fifth, to Vincent:

Vincent’s God is more loving than fifth’s because he gives apostates a final chance at salvation at the moment of death.

Here are a couple of excerpts from an exchange I had with Vincent:

keiths:

Vincent:

There’s a lot to criticize in that view, including its ad hoc nature. But at least Vincent sees the deep moral flaw in a God like fifth’s and chooses instead to believe in a better, more loving God.

God gives apostates another chance at any time especially at the moment of death, all they have to do is repent.

The problem of course is that apostates will not ever repent.

If they do repent they are not apostates at all even thought they claim to be but instead were never truly Christians in the first place. They never truly understood the Gospel or they would not have abandoned it in the first place.

Peace

When is the last chance?

The very last moment of your existence. I have no idea when that is.

It’s certainly possible that there is no last moment at all and God will keep you conscious after death for all eternity to insure that you can’t claim that you would have repented if you only had one more second

peace

Since there can only be one correct interpretation and many more incorrect , it is reasonable to assume obedience and incorrect interpretation often are found together.

Right, until you know stuff you don’t know what you are obedient to, and it seems if you are not obedient you don’t know stuff. For a timeless Being that may not be an issue, but man is not outside time.

He made us in the first place, He should know how to make us better.

peace

Wouldn’t that mean even an omniscient Being does not know the outcome of our choices before we choose?

newton,

If you don’t mind my asking what is the point of these questions?

I’m sure you know by now that I will be able to answer each and every objection you have. Christianity has been around a long time and most of theses sorts of questions have been dealt with over and over repeatedly in the past.

I know you are not really interested in all this. If you were you could easily locate a book to answer your questions with out wasting time in this little back and forth. And you know you will never change anyone’s mind by your constant questioning here.

So why do you do it? I’m sure there are topics you would rather discuss and while I don’t mind answering you I’m well aware that it is all a game and you will never be satisfied with my answers.

You seem like a pleasant enough guy. What drives you want to go round and round on this merry go round as FG called it?

peace

No, God knew what you will choose before the foundation of the world. The problem is you would not believe him if he told you.

My little speculation was based on the idea It’s possible that God will go exorbitantly above and beyond so that he could not ever be accused of not being patient and fair with you.

Of course it’s also possible that your last chance at repentance is one second away and this breath might be your last before your consciousness is forever annihilated .

A prudent man would not press his luck. Every single second of existance is infinitely more than we deserve

peace

After all this time you still are acting as if this is about you in some way, as if a correct interpretation is a reward for obedience or obedience or something.

It’s God who leads his people to the correct interpretation and it’s God who causes them to be obedient. This often happens at the very same time.

That only makes sense as obedience and correct knowledge are very closely correlated.

He does, That is what he is in the process of doing right now.

It’s called sanctification and it’s simply the outworking of the Gospel in our lives. It does not happen all at once (I suspect) because if it did we would take it lightly and not appreciate it as we should.

peace

You have got to be kidding.

How can you obey if you don’t know what is commanded?

peace