As The Ghost In The Machine thread is getting rather long, but no less interesting, I thought I’d start another one here, specifically on the issue of Libertarian Free Will.

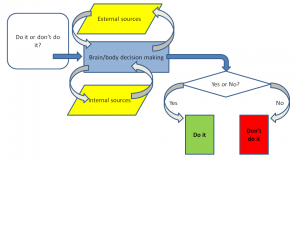

And I drew some diagrams which seem to me to represent the issues. Here is a straightforward account of how I-as-organism make a decision as to whether to do, or not do, something (round up or round down when calculating the tip I leave in a restaurant, for instance).

My brain/body decision-making apparatus interrogates both itself, internally, and the external world, iteratively, eventually coming to a Yes or NO decision. If it outputs Yes, I do it; if it outputs No, I don’t.

Now let’s add a Libertarian Free Will Module (LFW) to the diagram:

There are other potential places to put the LFW module, but this is the place most often suggested – between the decision-to-act and the execution. It’s like an Upper House, or Revising Chamber (Senate, Lords, whatever) that takes the Recommendation from the brain, and either accepts it, or overturns it. If it accepts a Yes, or rejects a No, I do the thing; if it rejects a Yes or accepts a No, I don’t.

The big question that arises is: on the basis of what information or principle does LFW decide whether to accept or reject the Recommendation? What, in other words, is in the purple parallelogram below?

If the input is some uncaused quantum event, then we can say that the output from the LFW module is uncaused, but also unwilled. However, if the input is more data, then the output is caused and (arguably) willed. If it is a mixture, to the extent that it depends on data, it is willed, and to the extent that it depends on quantum events, it is uncaused, but there isn’t any partition of the output that is both willed and uncaused.

If the input is some uncaused quantum event, then we can say that the output from the LFW module is uncaused, but also unwilled. However, if the input is more data, then the output is caused and (arguably) willed. If it is a mixture, to the extent that it depends on data, it is willed, and to the extent that it depends on quantum events, it is uncaused, but there isn’t any partition of the output that is both willed and uncaused.

It seems to me.

Given that an LFW module is an attractive concept, as it appears to contain the “I” that we want take ownership of our decisions, it is a bit of a facer to have to accept that it makes no sense (and I honestly think it doesn’t, sadly). One response is to take the bleak view that we have “no free will”, merely the “illusion” of it – we think we have an LFW module, and it’s quite a healthy illusion to maintain, but in the end we have to accept that it is a useful fiction, but ultimately meaningless.

Another response is to take the “compatibilist” approach (I really don’t like the term, because it’s not so much that I think Free Will is “compatible” with not having an LFW module, so much as I think that the LFW module is not compatible with coherence, so that if we are going to consider Free Will at all, we need to consider it within a framework that omits the LFW module.

Which I think is perfectly straightforward.

It all depends, it seems to me, on what we are referring to when we use the word “I” (or “you”, or “he”, or “she” or even “it”, though I’m not sure my neutered Tom has FW.

If we say: “I” is the thing that sits inside the LFW, and outputs the decision, and if we moreover conclude, as I think we must, that the LFW is a nonsense, a married bachelor, a square circle, then is there anywhere else we can identify as “I”?

Yes, I think there is. I think Dennett essentially has it right. Instead of locating the “I” in an at best illusory LFW:

we keep things simple and locate the “I” within the organism itself:

And, as Dennett says, we can draw it rather small, and omit from it responsibility for collecting certain kinds of external data, or from generating certain kinds of internal data (for example, we generally hold someone “not responsible” if they are psychotic, attribution the internal data to their “illness” rather than “them”), or we can draw it large, in which case we accept a greater degree (or assign a greater degree, if we are talking about someone else) of moral responsibility for our actions.

In other words, as Dennett has it, defining the the self (what constitutes the “I”) is the very act of accepting moral responsiblity. The more responsibility we accept, the larger we draw the boundaries of our own “I”. The less we accept, the smaller “I” become. If I reject all moral responsibility for my actions, I no longer merit any freedom in society, and can have no grouse if you decide to lock me up in a secure institution lest the zombie Lizzie goes on a rampage doing whatever her inputs tell her to do.

It’s not Libertarian Free Will, but what I suggest we do when we accept ownership of our actions is to define ourselves as owners of the degrees of freedom offered by our capacity to make informed choices – informed both by external data, and by our own goals and capacities and values.

Which is far better than either an illusion or defining ourselves out of existence as free agents.

Lizzie,

I think this is a useful, practical perimeter to put around “I” or “self” from a moral standpoint. I’m confused, though. This, you allow, is not “Libertarian Free Will”, but from my vantage point, it’s not “free will” at all. That is, setting LFW aside (it’s an incoherent notion we can set aside for our purposes, here), being a “bigger self”, with a large boundary around my actions which I take responsibility for doesn’t alter my agency in any way. Or, conversely, a “zombie Lizzie” who eschews all moral responsibility is precise as “free” as someone else who takes a maximally expansive view of their moral responsibility for their actions.

If our choices are driven by desires, constraints and prior causes which we could not have reviewed and chosen, or possibly also just by random “coin flips” in the brain, then our “perimeter”, the size of our ‘I’ in terms of accepting moral responsibility for our actions is no more “freely chosen” (in the superstitious LFW sense) than anything else.

You say:

I endorse this suggestion. But I don’t see how any of this gets you to this:

I’ll allow that I’m not clear on what you mean by “free agents”, here, but I do know that I, and a great many other people, have a strong intuition of LFW. I don’t see (or need, frankly) any escape from accepting that LFW, to the extent we intuit it or “see” it is an illusion, a falsehood.

I commend acknowledging our degrees of freedom as the basis for responsibility, where “freedom” here means potential for action independent from other minds — our choices may be fully determined, but they are discrete choices belong to the self, and not anybody else. I take that to be what you mean by “free agent”, and that’s good. Choices that are sourced to a particular mind (a particular individual) provide the semantic freight for “free”, here, I suggest. “Free will” in this case is actually better expressed as “Determined actions that are individual-centric, belonging to this individual/mind, and not any other individuals”.

This is coherent, and provides the foundations for assigning moral responsibility. I may not be able to choose how I act in any cosmic or final sense, but so long as my actions and choices can be assigned to *me* and not someone else, then culpability and consequences can also be assigned in practical ways.

I guess I’m counting “degrees of freedom”. A simple animal, like a moth, has few degrees of freedom, which is why it ends up flying into candle flames, although I guess it can probably decide to eat if hungry and not eat if not.

The more complex the animal, and the more behaviours at its disposal, and the richer the decision-tree that precedes the output, especially if the decision-tree includes re-entrant loops in order to seek further information if required, or to consult the potential benefit to some hypothetical self or other at some future time, or even compliance with some abstract belief system, also grounded in both prior experience and cultural learning – the more Degrees of Freedom it has at its disposal.

I don’t want freedom to act in any possible way – I want freedom to act in sensible ways, which means that freedom, if it is to mean anything, is necessarily constrained. If we don’t want to call that “freedom”, fair enough, but freedom is what it feels like. People who lose their sense of inhibition or constraint tend to feel “out of control” and indeed impulsivity is a clinical symptom of a number of psychiatric disorders – precisely those conditions when we tend to regard people as not fully “responsible” for their actions.

eigenstate,

Well put, and that is why I take a hybrid position:

I think that libertarian free will is incoherent and does not exist.

I think that compatibilist free will does exist, because nothing could be freer than to make decisions based on one’s own knowledge, character, desires and deliberations. As Dennett put it, it is the only kind of free will worth wanting, and it depends on the “degrees of freedom” that Lizzie described.

And though I think that compatibilist free will exists, I don’t think that moral responsibility does, for exactly the reasons you cited. Our decisions are ultimately rooted in constraints and causes outside of our control, so we cannot be responsible for them in any ultimate sense.

To put it differently:

1. We don’t choose our selves, and even if we did, the choices we made would depend on our prior, unchosen selves.

2. Thus every choice we make is rooted in causes and constraints that lie outside of us.

3. We cannot therefore claim ultimate responsibility for anything we do, good or bad. Moral responsibility is a fiction.

4. Compatibilist free will is a kind of free will worth wanting, even though it does not grant us ultimate responsibility for our actions. We make decisions based on our nature and our delberations, sure, but those were not (and could not have been) freely chosen in the ultimate sense, for precisely the reasons that libertarian free will is incoherent.

Lizzie,

Yes, Hofstadter’s concept of “hunekers” as the unit of the size of soul comes to mind — a mosquito is “small souled” at least substantially due to the rudimentary freedoms it has. A human, with many, many more degrees of freedom to operate (in the sense of autonomy, distinctness from other individuals, not LFW).

I’m all for repatriating the the term “freedom”, tying it to degrees of freedom of action in the individual.

keiths,

Concur.

Yes. I’ve talked to compatibilists who are clearly have not given up on LFW, but from what I read from the crew here, I’m on board.

As for Dennett, he gets kudos for breaking down the woo regarding quantum indeterminism and free will, but as far as I know, he’s still advancing this idea of foresight being the “free will in the most most meaningful way”, or something to that effect. According to Dennett (IIRC), if I see a big storm coming over the horizon toward the homestead and I start closing the shutters and battening down the hatches, etc., I’m exercising a form of “free will in a deterministic universe”. Maybe that’s just some semantic acrobatics I’ve missed, but that seems quite odd from Dennett — oddly romantic and like an effort to ‘throw a bone’ to all those who have angst over the discovery that free will is illusory.

Anyway, that’s a bit far afield. I agree with the idea that Lizzie and you and others have advanced; the most robust freedom we can exercise is to be “determined by our internal states” interacting with our environment. Our internal states are the “I”, and even if they are fully products of a clockwork determinism, they our “of the self”, free in the sense that they nobody else’s, independent of all others.

Yes, but “ultimate sense”, and “absolute” are words for fools, huckster’s terms, in general. If you tell me my life has no “ultimate meaning”, I just smile and shrug; that kind of meaning would be meaningful to me, and couldn’t be, even if was a coherent concept. I walk off down the road with my son, talking about baseball, and life is rich with non-ultimate, local, but substantial and real meaning.

Same thing with morality. “Ultimate morality” is an oxymoron, yet another incoherent concept. Even if we are clockwork automatons (and that’s not my view at all), morality as social construct not only obtains, but is necessary for individuals of a social species.

Only if we grant the LFW-centric sense of “moral responsibilty”, or some “ultimate morality”. I won’t push this idea here (further off topic, I think), but it’s crazy to even bother with the nonsense of “ultimate responsibility” or “ultimate morality”. This is to incorporate “square circles” into your geometry proof. Morality and accountability and (hard) consequences obtain and are effective in contexts where the agents are clockwork automatons, even. All that’s needed is for the agents to be capable of incorporating feedback into their future decision making (learning), and you have the basis for morality, accountability and social compacts.

I don’t disagree, but I always feel like compatabilism is borne of bad motivations; it’s either a) an anodyne balm for our minds which are scandalized by the realization that LFW or free will generally does not and cannot obtain, or b) a kind of apologetic we offer up as a bit of lawyering for rhetorical purposes in speaking with theists and others who cling to the superstition of LFW, or c) both.

That doesn’t mean your #4 here is wrong per se, but it’s always felt “spinny” to me. I can totally get behind “free will as the manifestation of an individuals degrees of free action, no matter how determined choices and actions are”; that’s coherent, practical, evidence-based. But I think it’s also just an overturning of the superstitious meaning of “free will”. Compatibilists (and I’ve done this, just not so much of late) often feel obligated to placate themselves and others that something like the intuitive sense of free will actually obtains. If that’s not disingenuous, I think it often comes close. The reality is nothing like our intuitions suggest it is, and I think it’s better just to be starkly upfront about it.

eigenstate,

I can assure you that my motives are as pure as the driven snow. 🙂

My short answer to the question “Does free will exist?” is “Not the kind of free will most people believe in”, and that is about as honest and complete as I can be in a single sentence (though if my interlocutor is game, I’m usually willing to spend many more sentences conveying the nuances of my position).

The problem is that neither an unqualified “yes” nor an unqualified “no” suffices as an answer to that question. If you say “yes”, most people take that as an affirmation of libertarian free will. If you say “no”, most people take it to mean that we are dominated by alien forces outside of our control, and that any sense of freedom we have is illusory. Both ideas are wrong, and both are implicitly dualist.

The dualist underpinnings of LFW are fairly obvious, but it’s worth expounding on how the second view depends on an implicit dualism. To say that we lack free will because we are dominated by forces outside of our control is to insist on an “I” separate from those forces. But if materialism is correct, the self is realized through those forces and is not separate from them. The laws of physics enable us to be our true selves, rather than preventing this from happening.

We inquire, evaluate, deliberate and decide according to our own natures. While it’s true that we are bound by these processes and cannot arbitrarily transcend them, they are also somewhat paradoxically the source of our freedom, because without them our very selves would become causally irrelevant to our decisions and therefore inefficacious.

It’s not the kind of free will most people believe in, but I do think that it is freedom in a genuine sense.

I read Dennet’s Elbow Room way back when I was a teenage student. Unintentionally (I think), it made free will seem utterly unimportant to me. I don’t see that it is helpful to use the label “free will” with all the baggage it inherits. Moral responsibility doesn’t require it. I don’t think it is a stretch to say that one of Asimov’s robots obeys a (simple) moral code. In a practical sense, what matters is the result, not the process or the feelings that go with it.

I think THIS is a valuable phrase. Perhaps the strongest qualification it needs is “if dualism is incorrect”, if any, although I suppose sadly a Buddhist would think it an empty statement.

Lizzie, you are really trying har to evade the problem.

Are you free to define your I? Are you free to accept moral responsability? How it happens? Is it a physical process that depends on the inputs?

You moved the problem of the materialistic model of reality from one box to another. The problem still remains. With the materialistic model you have only one rational answer and is the Coyne answer.

No, I’m not trying to evade any problem, Blas. Indeed, it is because I do not wish to evade the problems I see inherent in “Libertarian Free Will” that I am proposing a different approach to the concept of “freedom”.

Yes, I am as “free” to define my “I” as I am to do anything – it’s a choice, like any choice.

I absolutely agree with Jerry Coyne that if we define “free will” as “Libertarian Free Will” we don’t have it. Not only don’t we have it, but it’s not even have-able. It makes no sense.

Where I disagree with Coyne is that I think that considering ourselves authors of our own actions is perfectly sensible – not an illusion at all. It is no more an “illusion” to think I am free than it is to think that it is to think that such a thing as an agent called “I” exists. Or that an agent called Blas exists. It is perfectly sensible to say that “I” wrote this post and “you” wrote the post I am responding to. It is perfectly silly to say that “I” did not write this post, but instead a cascade of untraceable and irresponsible events going back to Big Bang wrote it.

Positing intentional agents in the world is a very good way of parsing it – it allows us, for example, to distinguish between inanimate things like rocks and thunderstorms that wish us no ill, and animate things like polar bears and soldiers that may. To avoid rocks and thunderstorms we just have to keep out of the way. To avoid being killed by polar bears or soldiers, we may have to figure out their intentions, and their likely choices.

We, like polar bears and soldiers, are choosing-things. Rocks and thunderstorms aren’t. I’m happy to call that capacity to choose, “freedom of choice”. After all, if a choice wasn’t free, it wouldn’t be one.

Yes you are, it is the usual way to evade question redefine terms.

Nobody even Coyne post that knew that we are

authors of what we do cannot be explained in the materialistic model of reality. The discussion is if we chose to do or not to do freely and the with responsability.

You are here adding intentionality to what we are discussing. And that could be a sinonim or not of free will depending on how you define it.

Intend an amoeba to follow the path of light? or is just the effect of the light that provoque the amoeba moving toward it?

The german sheeper that killed the eighteen month baby near Siena Did it “intentionally? Or was a more complex systems of reflexions similar to that moves the amoeba? Are our actions similar to the actions of a german sheeper but more controlled due to our education(more information)?

That is the whole point. There is any thing free in a materialistic model of reality? Given all the same conditions can matter respond in differents ways but not ramdomly?

What am I evading?

If you say to me: have you got $5? and I say, no I haven’t, but I do have £5, I am not “evading” your question.

And if you say: have you got 5 drachmas?, and I say, no, I haven’t, and drachmas aren’t even legal currency any more, but here is €5, which is, I am not “evading” your question.

I’m saying: no, I haven’t got Libertarian Free Will, and nor have you, and Libertarian Free Will isn’t even a coherent concept, but here is another kind of freedom to act with intention, and which is a lot more useful, because it actually works.

Of course I wasn’t impugning your motives here. I hope that’s clear.

Understand. I’ve decided that “free will”, delivered just as you’ve offered it here, is generally counterproductive for me, so I don’t use it much any more. But that is really just facing facts about the preconceptions and biases I’m typically dealing with. I agree that, for a fair listener, that’s as good a response as is to be had. Taking stock, the people who believe in LFW generally cannot make the jump to “a different view of ‘free will'”, and the people who don’t believe in LFW do not need to salvage the term.

If this sounds like I’m being contrary, I’m not intending such. I can nod without reservation to what your saying, and have taken similar positions in the past. “Free will” just ends up being a tar pit of a term for me when engaging others on the subject. I can chalk that up to being more clumsy than you in making my points, though, having read a lot of your stuff now.

Yes. I’d like to salvage the term “soul”, for example, and deploy it in meaningful, secular ways like Doug Hofstadter advocates. But I think “free will” may be unsalvageable, as a term.

Very well put. I’m tempted to plagiarize this paragraph. 😉

Right. Forgetting notions of determinism and libertarianism for the moment, what makes our freedom actual and meaningful is the “topology”, the partitioning of phenomena into chunks of processing and action we call “individuals”. We are “free”, even and especially (this is your paradox) in a clockwork determinism because we are *distinct* as a subsystem function as a discrete part of the whole. Our (determined) stats are local to the self, the individual organism, and not just diffuse phenomena interacting with the rest of the environment.

Agreed. Our only difference here I think is my more dark and cynical view of the prospects of this point succeeding in the current culture with all the baggage that comes with the term “free will”.

Yes indeed.

Lizzie:

If you say to me: have you got $5? and I say, no I haven’t, but I do have £5, I am not “evading” your question.

Your example doesn´t fit. I am asking if you have a dollar and you say no, but I have a piece of papar with a draw of the face of Washington in green ink and the people accept change that piece of paper if I want something from tham.

Lizzie:

I’m saying: no, I haven’t got Libertarian Free Will, and nor have you, and Libertarian Free Will isn’t even a coherent concept,but here is another kind of freedom to act with intention, and which is a lot more useful, because it actually works.

You cannot know what I have or not. But this is not the problem, the problem is how can a materialistic model of the reality can explain not only the intention of the act, but the freedom.

You have to explain how matter can have will, and then if matter that will can chose with the same information between two “outputs”.How is different the reaction of an amoeba, a dog or us? What make you different?

PS After read your “The Laws of Though” I find that only a miracle of bayesian probabilities can explain that for you.

Well, the output of an amoeba is very different from the output of either a dog or us. We are much more like dogs than amoebas.

The big difference, I would say, is the capacity to compare several potential actions and choose the one that best matches our goals, whether short or long term (also a choice).

We are better at that than dogs, but both dogs and people can do it, amoebas can’t.

You are only saying that are different, not why and what make us differents. Basic mechanism of action in dog and humans are very similar to amoebas actions. And can be explained by chemistry reactions like in amoeba. Pavlov´s dog start producing saliva because he forsee the food coming like we act trying to reach our goals? When we take away our hand from a flame are acting like an amoeba, what make different my choice for chocolate icecream?

Cats! They’re the real masters of the universe.

Well, no. We are multicellular animals, and we have brains. An amoeba is a single celled animal with no brain. The mechanisms of action are vastly different.

Classical (Pavlovian) conditioning as well as operant condition are certainly important mechanisms of human learning, but they are not the only processes that govern our behaviour. For instance, you might be conditioned to like chocolate ice-cream because it is always followed by a ride on the roller-coaster, but you might nonetheless refuse it because you know it will make you fat, or because you know it has been produced by slave labour.

True. I don’t know any other organism that gets more pleasure for less effort.

Blas, to get the analogy more accurate, you are not asking Lizzie if she has a dollar. You are asking if she has a Blasnotski. She is saying such currency doesn’t exist, but here’s a pound.

Vastly different? Physical signals transformed in chemical energy like ATP that produces an effect in the cell. Are really Vastly different? or the difference is like my old calculator and a modern PC?

True, but knowing that it will make me fat or it has benn produced by slave labour are not conditioned in the same way that wanting chocolate because followed by a ride? The three decisions are made by the same brain, that is made all by neurons that do not have substancial differences between them.

What difference you immagine can support the big claim that our action could be so different from a conditioned reflex?

Sorry you do not re following right the discussion. I am waiting that Lizzie tell me Blastnotski that not exist, but she is answering Blastnoski do not exists by I have a pound that has the same properties than a Blastnotski because she want to have the properties of a Blastnotski but do not admit it exists.

Blas,

If English is not your first language, use short sentences. Your long sentence seems to have been lost in translation.

A small question: may I assume that “Libertarian Free Will” means free will as exercised by people who object to paying income tax? Are those of us who aren’t libertarians eligible to have it?

Yes, libertarians are the only ones who get their will for free. The rest of us have to pay for it.

They are completely devoid of anything I would call ‘morality’. It does appear to make life simpler.

[unnecessary addendum for anti-materialists: For Them. This is an observation, not a manifesto].

Humans aren’t in a position to judge cats.

Huh! My daughter’s cat judges me. I can see it in the eyes.

That’s one reason I’m a cat person. They judge severely but fairly, thus inspiring their humans to do their best.

To earn the approval and affection of a cat is a real achievement. They aren’t promiscuous attention sluts like dogs.

If they weren’t so goddamned cruel … (an interesting conundrum for the objective-morality brigade. Something I find abhorrent is a matter of routine for one of The Arbiter’s other creatures)

Cats are not cruel. What they do is cruel, but they are incapable of knowing what the object of their torture is feeling. Actual moral cruelty requires being aware of the feelings of the victim.

I’m sure everyone has a cat story. We have one that has gotten too old to hunt, but when when younger he brought us gifts several times a week. The rats he killed. Everything else he caught, brought in through the cat door and released in the house.If we were gone for a few days we could count on getting a gift the morning after we got back.

I’m not saying that my pound has the same properties as a Blasnotski. I’m saying that a Blasnotski has no properties, but that my pound has.

The properties usually attributed to the Blasnotski.

Some of the properties usually attributed to the Blasnotski.

The Blasnotski is incoherent and cannot exist. The pound exists, and it exhibits some of the properties usually attributed to the Blasnotski, minus the incoherent aspects.

Magic.

When one says that “they” are “free” to define their “I” and to accept moral responsibility, what does that mean? What are “they”? What does freedom mean? What is the “I” they are talking about? It’s all the same thing – the material computation deciding what they are and will do, what freedom is and what it means and how the “I” is defined, and what “moral responsibility” is and how the “I” will interact with it. There’s no “freedom” or “I” or “morality” other than what the computation happens to generate.

Unless there is freedom from that computation, then if the computation happens to generate a Dahmer in one instance, and a Gandhi in another, neither of “them” are “free” to be anything other than what the computation generates, because that is all they are, and all they can be. There is no “outside the computation” for either of them, nor any internal means to escape or override the computation.

When you speak of computation you are reifying a metaphor.

You cannot draw conclusions by saying brains are like computers and are therefore limited by the rules that govern computers.

You may make the assertion, but you shouldn’t be surprised if people who know what you are doing ignore you.

[Butterfly wind & pizza = metaphor for chaotic, unpredictable external and internal material causal factors.]

I agree that, in terms of cause and effect, LFW is an incoherent concept – because it cannot be described in such terms, other than as an anomalous uncaused cause. It’s like asking what caused the universe; it’s an incoherent question because it requires an answer in certain terms, and those terms are not applicable to that which is being examined. Metaphorically, the materialist demands that a 4-sided triangle is incoherent; but the non-materialist isn’t talking about a triangle; he’s talking about a pyramid. The non-materialist is talking about something necessarily inexplicable in the frame of reference the materialist is demanding.

In fact, LFW must be incoherent in terms of materialist explanations, because it is held as something that supervenes over such things in an anomalous state outside of cause and effect. How could it not be incoherent in such terms?

Perhaps to an ideology where all there is are materialist, cause-and-effect sequence descriptions, that means LFW is entirely an incoherent concept. However, not all of us are bound to such an ideology as that which explains the entirety of existence.

LFW, as a non-materialist concept, is not only coherent, but inescapably necessary. It is how we all must behave and how we all must argue. We must argue as if we, and those we debate, have the capacity to supervene over their material computation and can access the absolute; we do not, and cannot, argue as if butterfly wind and pizza (chaotic, unpredictable material input) is what actually convinces anyone of significant rational conclusions. We cannot live that way. We cannot actually think of ourselves that way in any operative sense.

From this perspective – from the “how we must actually think, argue and act” perspective, the computational model of will is incoherent, non-practical and effectively inapplicable. Nobody can act as if it is true that the “I”, and what we will, are entirely the material computations of butterfly wind and pizza.

I’m not reifying a metaphor, I’m using “computation” as a shorthand description of the collection of all material processes that generate, through cause and effect, whatever they happen to generate as effects at any particular point and location, including what what any particular set of matter “thinks”, considers as an “I”, concludes, and wills.

IOW, petrushka, you are the one tying my use of the word “computation” to the limitations and rules of a computer, not me. I’ve made it clear what I mean when I use the word.

The term “computation” correctly implies that there is no exterior will, no outside agencies involved. All wills, all agencies, are generated within and by the material computation as it proceeds. Everything those wills decide, choose, or consider is all generated by the computation, whatever those rules, parameters and limitations may be, even if it cannot be predicted and even if it is non-deterministic.

All of your terms, including cause and effect, are overexrended metaphors. You cannot apply pre 20th century understanding of cause and effect.

LFW is taken as (premised) an entirely free, anomalous uncaused cause, not bound to material computations – not bound by butterfly wind and pizza. Let’s presume arguendo that it is a distinction that provides no distinguishable observable or experiential effects from being a biological automaton.

In this case, the concept that we are biological automatons would be equitable to the concept that we are Boltzmann Brains having a delusion; we cannot actually live and act and think as if such was true (for the most part, anyway). So what does it gain us to intellectually, at least, hold this position? What effect does it have, psychologically? Could there be general patterns of consequences for holding either view – LFW vs BA?

There are certainly many people that can hold the materialist view that we are, essentially, biological automatons programmed by butterfly wind and pizza and continue behaving as if they still have free will and moral responsibilities … but is this true of most people? If you instill in your average Joe on the street the idea that they are the productions of Darwinistic, material computation – that absolute morality doesn’t exist, that there are no necessary (intrinsic) consequences (chaotic, unpredictable) to their actions, that even what they think and choose are effects of the chaotic and unpredictable interactions of material influences – how can we expect such input to affect Joe?

Should we expect the result of this input into Joe’s computation to be a more moral Joe? Why should Joe care about morality at all, if the moral and immoral are both computed outcomes of nature? If Joe is of the belief that whatever he does, he was computed to do, why should he feel guilt or remorse? Why should he care what others think, other than in how it serves his own interests? Research done into theistic and materialist pre-conditioning shows that people pre-conditioned to believe in this kind of materialist perspective tend to behave less ethically and less morally, while those pre-conditioned with theistic concepts behave more ethically and morally.

If one actually believed they were a brain in a vat (or a Boltzmann Brain, then harming others would be like harming someone in a dream. So what? The only thing you have to account for is what you do not have control over in your delusion; the same is true in the moral system in biological automaton in a world of biological automatons; do whatever you want, whatever is in your own interests, as long as you feel like you can get away with it, because there is no predictable outcome for harming or helping others, or for doing what others consider good or evil.

As a mathematician, I’ll point out that your use of “computation” is totally bogus.

It has become traditional to define computation in terms of a Turing machine. The “Turing Machine” is typically defined as an abstract machine. Or, to put it differently, computation is inherently abstract, so is inherently immaterial. That box on your desk, as a physical material object, is an electrical appliance that does intricately detailed electrical operations. We normally think of it as computing, but that comes from applying an immaterial interpretation on what it is doing. Numbers are not material objects. Logic 0 and logic 1 are not material objects.

Yes, many materialists think that the brain is a kind of computer. But they are using “computer” as metaphor. As far as I know, there is nothing about materialism that compels a belief in computationalism.

So what is your point?

Feel free to provide your current understanding of cause and effect, and how it undermines the basis of the arguments I’ve made, if you can.

Other studies have shown, and there has been research to support, that those who consider their “free will” or “mind” to be something other than their brain (meaning, something not “computed” or “generated” by material forces) to have greater capacity for self-control in medical conditions like OCD. People that are pre-conditioned to view “themselves” as an agent beyond their brain and entirely autonomous, and see certain things as errors of brain computations or processing, have more power to change behaviors.

This points to the general influence of how average people respond to the LFW vs BA concepts, and to generally theistic vs materialist pre-conditioning. While it certainly doesn’t apply to everyone, such conditioning cannot help but affect one’s behavior via their psychology.

There are certain concepts that are very powerful that affect people in generally predictable ways – whether they rightly or wrongly interpret such concepts, and whether they rightly or wrongly apply them. Both LFW vs BA are two very powerful concepts that, rightly or wrongly interpreted, and rightly or wrongly applied, affect how people think and behave. IMO, LFW is the superior operative concept and has more of a generally positive effect on people than BA; I think the BA concept is a very slippery slope that can lead people more easily into immoral and unethical behaviors, whether or not the LFW concept is “incoherent”.

I have no idea what point you are trying to make. I see no intersection between anything you say and anything useful.

So the argument is now from consequence?

Rather you seem to think “libertarian free will” and “biological automata” have something to do with how you imagine other people behave. Me, I think you have no more idea than me about how human beings function at a neurological level and a lot less idea than many. Frankly, you still aren’t making any sense. My advice to you would be “first observe, then hypothesize”.

Since LFW is taken as a premise, the arguments have always been from consequences of that premise, one way or another.