I think a thread on this topic will be interesting. My own position is that AI is intelligent, and that’s for a very simple reason: it can do things that require intelligence. That sounds circular, and in one sense it is. In another sense it isn’t. It’s a way of saying that we don’t have to examine the internal workings of a system to decide that it’s intelligent. Behavior alone is sufficient to make that determination. Intelligence is as intelligence does.

You might ask how I can judge intelligence in a system if I haven’t defined what intelligence actually is. My answer is that we already judge intelligence in humans and animals without a precise definition, so why should it be any different for machines? There are lots of concepts for which we don’t have precise definitions, yet we’re able to discuss them coherently. They’re the “I know it when I see it” concepts. I regard intelligence as one of those. The boundaries might be fuzzy, but we’re able to confidently say that some activities require intelligence (inventing the calculus) and others don’t (breathing).

I know that some readers will disagree with my functionalist view of intelligence, and that’s good. It should make for an interesting discussion.

Computers don’t do real math. They only simulate doing math. All the answers can be found in books.

Therefore they aren’t useful.

petrushka:

Exactly. His argument really seems to be something like that. When pressed, he would probably admit that computers are useful, but then he’s faced with the obvious question: Why are computers so useful if the arithmetic they do is fake? And what distinguishes fake arithmetic from the genuine arithmetic that humans presumably do?

Current AIs have exposed a fatal flaw in the Turing Test.

They can converse so eloquently on every subject that their competence betrays them. And then they flub a response that a five year old could handle.

The things AI can’t do are the things that cats, dogs, monkeys and dolphins can do.

If I were forced to make a prediction, I would predict that AI will acquire more humanlike capabilities over time. How much time? Less than anyone imagined. Science fiction said 300 years. I think less than thirty.

Five years ago I thought self driving was extraordinary difficult. That was true, but it arrived anyway.

I asked Claude to invent a language with grammar different from English, and then to translate his Tic-tac-toe paragraph into it, stating the vocabulary and rules he was using. This was a much harder challenge for him, and he screwed up in a few places: omitting a pluralizing suffix where one was needed, messing up the word order in a sentence, forgetting that adjectives always come after nouns in his language. I didn’t describe his errors to him — I just asked him to double-check his work, and he found all but one of the mistakes. (A similar approach is helpful when using AI to code. Always ask it to double-check.)

ETA: I tried another couple of times in separate chats, and Claude did even worse.

It’s an interesting set of failures. I think he was having trouble ignoring the “urge” to use English-like constructions and sticking to his invented rules. Even though the words were invented, and he had never seen them before, he had a clear sense of their function: noun, verb, adjective — and the English rules for dealing with those sometimes overpowered the rules he had invented.

I won’t bore you with the translation, but to give you a flavor of the invented grammar, I asked Claude to do a literal, word-for-word translation back into English:

This has implications for the experiment I’m designing in which I’ll try to teach the AIs to code in a language that isn’t in their training data. Should be interesting.

Erik:

I still haven’t heard you explain the difference between all these supposedly fake activities and their real counterparts, other than simply declaring that when a machine does them, they’re fake — they’re only simulated, not real. If your premise is “Machines can’t be intelligent, because at most they can only simulate intelligence”, then your conclusion will be that machines can’t be intelligent. That’s boring, because no matter how capable they become, even doing genius-level work, you’ll declare that they aren’t intelligent. Like everyone, you’re entitled to your own definitions, but that isn’t how most people use the word “intelligent”. For them, there are activities that machines could do (or already do) that would qualify them as intelligent.

But back to your contention that all of these activities are only fake when a machine does them. If you ask an AI to write a story, it produces a story. It’s a real story, with characters, a plot, and a resolution. If you show it to someone without telling them that an AI produced it, they’ll describe it as a story. It’s a real story, but according to you, the AI is only simulating the process of writing. If so, why does a real story get produced? How can a fake story-writing process produce real stories? If the process is fake, why aren’t the stories fake?

If computers produce real sums, why regard their arithmetic as fake? If AIs systematically work through and solve physics problems, why is that fake problem-solving? If it’s fake, why do real solutions come out the other end? If an AI produces a paragraph describing the rules of Tic-tac-toe without using the word “the”, it’s a real paragraph, not a fake one. If the process is fake, why did it produce a real paragraph that honors the specified constraint?

Please stop avoiding the simulated-vs-real question. It’s central to the debate.

No, and I’ve given multiple examples of AIs generating original material.

Your plumber (unless they happen to be a computer geek) will start glitching if you ask them to write code in C++. They haven’t been trained in it. They’ll have trouble getting it to compile, much less produce the desired results. So what? What does that have to do with the question of their intelligence?

Erik:

keiths:

Erik:

Not so. Your plumber can fake being happy, but they can’t fake knowing how to program in C++ — not if you actually sit them down and ask them to do it.

keiths:

Erik:

Supporting argument, please. Why is self-cognition necessary? If an AI unifies GR and QM, but doesn’t have self-awareness, why does that make it unintelligent? For that matter, emotions don’t depend on self-awareness either. Do you truly think an animal can’t be content, or angry, or amorous without thinking of itself as content, angry, or amorous?

Plus, I gave two examples of Claude’s self-awareness above, in which he demonstrates meta-knowledge — knowledge about what he knows and doesn’t know.

Chatbots are deliberately designed not to go off and do things on their own, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t capable of it. Once a chatbot starts talking, it can go on indefinitely. The only reason it stops is because it’s trained to stop instead of blabbing on and on like Aunt Mildred.

Earlier in the thread, I mentioned that people are putting AI characters into video games and letting them loose to explore and learn. Those AIs are self-motivated. They aren’t constantly waiting for someone to tell them what to do, unlike chatbots. You’re mistaking a deliberate design decision for an inherent limitation of AI.

See above. Nothing prevents AIs from thinking and acting alone, other than deliberate design decisions.

I don’t know where you got that idea. Who are these physicalists who think that self-cognition doesn’t exist? If you ask one of them “How are you feeling today?”, do they answer “I don’t know. Who is this ‘you’ of whom you speak?” I know a lot of physicalists, and I’ve never heard them say anything like that. And even that would demonstrate self-cognition, because the speaker is referring to their own state of knowledge: “I don’t know.”

keiths:

It’s more like:

Same difference. You’re assuming your conclusion.

A while back, I read of an experiment of trying to teach chimps to drive cars. Turned out the chimps were very skilled drivers, but failed to grasp certain essentials. The chips understood, for example, that green means go and red means stop – but if you put a brick wall in front of the car and turned the light green, the chips always drove the car into the wall.

Self-driving algorithms suffer from similar lack of judgment. Human drivers (except teenagers) learn to assess their overall situation – all other nearby vehicles and what direction and how fast they are going, side streets and parking lots and whether anyone might drive out from one, pedestrians and what they’re doing (and their approximate ages, with knowledge of the judgment expected from pedestrians of varying ages), whether signs like stop signs have likely been improperly removed, some idea of mechanical failure like sticky gas pedal or flat tire, this list can become very long. Yet we all learn to develop awareness of all this. Self-driving algorithms struggle with both the awareness and the judgment applied to it. Perhaps most multi-vehicle accidents stem from someone doing something someone else failed to properly (or accurately) anticipate.

I don’t think I’d be very good at writing a driving AI that could actually recognize that a nearby vehicle was being driven by someone age 16 or 90, and plan accordingly. As of today, I think we’re a long way from programming “driving intelligence”. Many edge cases are handled well enough, but only those cases that can be anticipated and modeled. Anticipating the unexpected, now, that’ll take a while longer.

Flint,

Your comment reminded me of something I read the other day about a proposal to add white to the standard red, yellow, green of traffic lights. I’m not clear on the fine details of how this would work, but the basic concept is this: white means “follow the car in front of you”. The idea is that all of the self-driving cars will communicate with each other in order to coordinate the best way to maintain traffic flow while preserving safety. Humans who are still driving their old clunkers will treat red, yellow and green as always, but if they see white, I guess that means that the car in front of them is self-driving and is effectively running interference for them, so that all they have to do is follow it.

That’s all I know about it, from the single mini-article I read.

Computers indeed do not do real math. They only simulate doing math. But even abacuses are useful for doing math, computers even more so.

Who is doing math when an abacus (or computer) is used for doing math? Attentive people know the answer. keiths is not attentive.

Of course I have explained it. You just don’t listen.

Machines do not do anything of themselves at all. No machine ever does anything on its own. Humans build them for human purposes and make them do stuff. The difference is between the doer and that which is just a tool for the doer. When you do not push the beads of the abacus, when you do not turn on your computer, when you do not prompt your AI, it does not do anything.

Another way to explain it is with a difference between a map and the territory. The territory is the real thing and a map is its simulation. A country’s economy is the real thing and an Excel model about it is the simulation. The same between a thinking human and an AI.

For any average computer guy this is all self-evident and requires no explanation. But you are a deluded AI fanatic who forgot the basics. Now continue to not listen.

No, no, and no.

Just a few days ago you praised the AI’s ability to analogise. Your problem does not have to be exactly the same as in textbooks. It has to be similar enough. And for AI, amazing things are similar enough, such as chess rules, scoring points in beauty pageants, and vanishing balls under a magician’s cups – all similar. When trained on a topic rigorously enough (and physics appears to be one such topic, and image enhancement/generation another), I’m confident that AI can find a match that is passable for human preferences. And you should be confident too. Why are you suddenly calling it ludicrous?

And no, they are not reasoning their way to it. They show you how they are looking it up while they hide the potentially copyright-breaching or otherwise law-breaking elements from the user. This is all very well known. For example when Alexa was asked, a decade ago, things like “Do you spy on me?” and “Do you work for NSA?” it at first attempted an answer like “I only send audio back to Amazon when I hear the wakeword. For more information, view Amazon’s privacy notice” but eventually stopped answering. When the Chinese introduced their Deepseek and it was asked about censorship and democracy in China, it at first honestly started listing some issues, but within a minute erased this procedure and suggested other topics.

Conclusion: AI does not think on its own. It does what its makers made it to do, but its scope is too large to cover all the bases and to properly train it in most areas. The hope (of the owners) is that users will improve the half-ass product they got. You are a good customer, keiths.

And yet cars are on the road right now that can accommodate all kinds of erratic drivers. Even hostile drivers.

Your error is assuming that one has to code a response to every possible situation. This is not the case. Humans do not have a set of rules for every situation in life.

AI does not understand or create rules. It integrates input in a way that generates probabilities. Both AI and humans can behave in unfortunate ways. Probability implies a range of results.

Well, not exactly. What the AI must do is handle situations properly that it has never encountered before. That is, use a combination of learned experience, knowledge of your vehicle, and intelligent judgment. So far, as I read it, this hasn’t been achieved well enough, and self-driving cars continue to make mistakes a human would not. I’m optimistic that they will improve.

I agree that AI systems do not exercise autonomous initiative. Whether this makes them dumber than people depends on what you see as desirable. After all, people have created a vast system of laws and regulations, and nonetheless require depressingly large armies of lawyers to apply them to ambiguous situations – and all because people exercise independent initiative.

What you seem to be saying is that AI systems cannot really learn from experience. That they simply copy things extracted from some large body of training material, modifying them as necessary but never really creative. I think keiths has given examples that adequately demonstrate that this isn’t so. I believe that some AI systems are fully capable of writing, say, science fiction novels with believable characters, coherent plots, ingenious invented technology, sensible future societies, etc. And do a better job than some human authors, who tend to be under deadlines and paid by the word. I understand that such a system wouldn’t do it if it weren’t instructed to do it, much as a human author wouldn’t do it without some incentive, usual financial. But if the major difference here is the nature of the incentive, and one incentive is “intelligent” and the other is not, you are splitting hairs to win an argument.

I think you are equivocating here, conflating math with calculation. Computers are very good at calculation. But there are plenty of math problems or conjectures that have been posed, and nobody has yet solved them (and now and then you read about a solution to some long-intractable problem). To me, proving or disproving such conjectures is real math. It ain’t calculation, grinding out solutions to established equations. I wonder if anyone could distinguish “real” from “simulated” arithmetic without knowing who or what performed it.

Every real life situation in driving has never been encountered before.

Some possible categories:

1. Map locations never encountered before.

2. Streets that are not marked, or where the markings have been damaged or vandalized

3. Unpaved roads

4. Streets flooded or temporarily blocked

5. Stalled vehicles

6. Traffic signals not working

7. Malicious drivers, or drivers breaking laws

8. People or animals in the road, or about to cross the road

9. Objects in the road, or new potholes.

All of these scenarios are being well handled by the latest systems. As well as or better than average humans. Possibly not as well as the best human drivers.

The first hurdle is to be safer than average. The grail is to be better than really good human drivers.

Both Waymo and Tesla have taxis operating in large cities and on expressways. Some of my claims apply to versions that are only weeks or months old. Tesla is currently releasing updates pretty much every month.

Flint:

The answer is no, because they’re identical in every respect except for the entity performing them. That’s important, because we rely on computers to track our account balances, design our airplanes, predict the weather, etc. Those calculations are all fake, according to Erik. If fake math didn’t mirror real math, the result would be chaos and destruction. Erik’s distinction is goofy. If fake math does everything that real math does, there’s no reason to differentiate the two unless you have an ideological ax to grind, as he does. “Computers only simulate math” is just a version of Erik’s premise that “all machines lack intelligence.”

His position isn’t just goofy, it’s also incoherent. On the one hand, he says that computers only do simulated math while humans do it for real. On the other hand, he says that when a computer does math, it’s really a human or humans doing the math, because they are the ones who create and manipulate the computer. So which is it? Are the results fake because a computer is producing them, or are they real because a human is producing them using the computer as a tool?

Yes, this is what I’m saying. If you disagree, tell me what it is that AI experiences such that it can learn from the alleged experience. I say it experiences exactly nothing.

Just no. First, strictly speaking, AI does nothing and it experiences no incentive whatsoever. And whatever it writes (or paints or “thinks”) draws from its database without adding anything new. There is no true creativity, only combinations that may surprise the gullible, but the combinations draw on the existing elements of the database.

And you misconstrue humans too. I personally happen to be creative exactly in the form of writing and I have written thousands of pages “into the drawer” on my free time whenever I could. Instead of some financial incentive (which has been zero) I have had a *disincentive* in the form of a dayjob that has nothing to do with writing, yet I have written a lot despite of the disincentive.

No, I’m not equivocating. I just use the same vocabulary that keiths uses. He is adamant that computers do math – for emphasis, computers do even real math according to him.

I always made a distinction, even while limiting myself to keiths’ vocabulary. The distinction is between real (or true) and simulated math.

Careful, one might easily detect an equivocation here. Strictly speaking, computers do not calculate. Rather, humans calculate and they can do so with the help of an abacus or a computer or they can invent more tools to help with calculations.

Different from you and keiths, here is someone who seems to somewhat know what he is talking about

The video presents the problem: Since the “learning” (or “experience” if you prefer) of an LLM is as large as its database, there is a scaling problem. It can only learn by upsizing its database which is already humongous and this does not scale.

Proposed solution: “Reinforcement learning (RL) agents that are efficient enough to learn from a single, embodied stream of data.”

I would counter that this seems to go back to the beginning of the history of chess engines, where the first approach was in fact lean and mean: Enter the chess rules and define victory for the machine. And then expect it to play perfectly, because it is a machine and therefore it must behave as expected. It cannot make a wrong move because it knows only right moves. Well, this approach turned out painfully inadequate.

Nobody has yet seen a machine that really learns. What we are seeing in modern LLMs is training data in such egregious amounts that even the machine has trouble digesting it. And this is what has been labelled “machine learning” in marketspeak.

So is an earth mover digging ditches just simulating digging?

There may come a time why we have to ask the Asimov question: do AI computers merit human rights and citizenship.

We are not there, and perhaps no one currently alive will be faced with that question.

The practical question is whether AI will discover new things, invent new theories, or prove mathematical conjectures.

These are real questions

The answer to this is that it’s the wrong thing to wonder about. The difference is exactly in the process, not in the result. It’s the process that is either real or simulated.

Let’s take some supercomplicated arithmetic, like about the economy. When given statistics about the economy and an economic forecast for the future, you know for sure that there were some computers involved in producing the result. But do you think the computers “know the economy” or “experience” it somehow? Grownup people are normally aware that there were some economists who modelled the economy in Excel or (perhaps better) Python and ran the numbers through the model. It’s the economists who know the economy (or they know it badly). For reasonable people, the question How much economy does Excel (or Python) know? does not arise. Hardly anybody wonders whether Excel’s (or Python’s) knowledge of the economy is real or simulated – for most people it is instantly and eternally self-evident that there is nothing like knowledge in Excel or Python in the first place, much less “experience” or other such words that physicalists consistently fail to define. But in a debate with someone who is very convinced that there is knowledge and intelligence in the machine, the appropriate answer is that insofar as intelligence seems to be there it is, alas, simulated.

Nobody ever attributed any intelligence to Clippy. But then keiths met Claude…

I think you underestimate how good AI has become at finding patterns.

And how much better it will become.

But the interesting question is, how much damage can be done when multiple AIs try to leverage the same trend at the same time.

This has already happened.

Erik, to Flint:

Are you conflating experience with sentience? AIs aren’t sentient, but they do experience: they learn, they get prompted, they solve problems, all of which counts as experience and affects their future actions.

So you say, yet this thread and others are filled with examples of AIs doing things.

Only if you conflate experience with sentience. AIs do have incentives — that’s what reinforcement learning is about. And they’re motivated: LLMs are motivated to respond to your prompts instead of just sitting there or saying “Buzz off, human. I don’t feel like doing your bidding.” AI Agents will reserve a table for you when you ask instead of ignoring you and amusing themselves by composing haiku. They’re motivated to satisfy your requests.

That’s like saying there is no true creativity in Shakespeare — just combinations of existing words that surprise the gullible. (And lest you’re tempted to reference James Joyce or Lewis Carroll, I’ll point out that AIs can invent words too.)

You still have an incentive or incentives. It’s just that they aren’t financial. You could, for instance, be doing it simply because you enjoy the process of writing.

A guy has a complicated program he needs to run which will generate a ton of data. He decides to run it overnight so he’ll have the data in the morning. He starts the program, goes to bed, and falls asleep. He dreams about unexpectedly encountering his dentist while trekking through the Kalahari, and then about being caught in flagrante delicto with Rod Stewart’s wife. (I actually had the latter dream once.) Nary a thought about his program or the data it’s generating, yet according to you, he’s calculating all night. Why? Because the computer can’t calculate. The man is calculating through his computer while he sleeps. Neat trick, right?

Later that same night, he dies in his sleep. Yet he continues to calculate, because the computer is still calculating. The man is calculating from the grave. That’s an even neater trick than calculating while asleep.

Or you could just accept the obvious, which is that although the man is using the computer as a tool in order to obtain the numbers, it is the computer itself that is doing the calculations and producing those numbers.

How this conversation has been going:

Is there a way we can get you out of this rut, Erik? The question is whether AIs are intelligent, not whether they’re perfect. You’ve been trying so hard to show that AIs aren’t intelligent, but you’re not recognizing that your “proofs” also show that humans aren’t intelligent, which is not what you’re hoping to accomplish.

Training is learning, both in machines and in humans. There’s a reason it’s called “machine learning”.

Flint:

Erik:

Human arithmetic is a real process taking place in human brains that produces real numbers. Computer arithmetic is a real process taking place in CPUs that produces real numbers. Computer arithmetic is just as real as human arithmetic.

Your arguments collapses to this:

P1: If a computer does it, it’s only simulated.

P2: Computers do arithmetic.

Conclusion: Therefore computer arithmetic is simulated.

You’re simply declaring P1 rather than justifying it. Can you come up with a justification other than “because I say so”?

3 + 3 = 6 is real arithmetic, regardless of whether we’re talking about ducks, dollars, or degrees Celsius. Computers operating on abstract numbers are still doing real arithmetic. Humans are like that, too. If you ask a normal human what 3 + 3 is, they’ll say ‘6’. They won’t need to ask whether you’re referring to metaphors or toenails or gaffes.

Also, AIs can associate numbers with their referents (in cases where the numbers aren’t abstract). If you ask an AI how many fingers there are in a group of 5 normal people, they’ll know that that ‘5’ refers to people, ’10’ refers to fingers per person, and ‘5 x 10 = 50’ refers to the total number of fingers in the group.

What precisely is missing from the AI finger calculation above that is essential to intelligence? If you say “the AI calculation isn’t intelligent because it isn’t being done by a human”, you are simply assuming your conclusion again.

Claude would blow Clippy away on any standardized IQ test. It would be even more lopsided than Jasmine Crockett vs Donald Trump.

petrushka:

Sure it does. Remember my earlier example where I asked Claude to summarize the rules of Tic-tac-toe without using the word “the”?

He understood the rules well enough to state them, he knows them well enough to play Tic-tac-toe with the user, and he understood and followed the rule I gave him about not using the word “the” in his description.

I do not wish to duel over semantics.

Long before LLMs became powerful, I expected AI to be susceptible to the same kind of errors as humans. I believe I posted this some time ago. Maybe not on this site.

The source of error is baked into reinforcement learning and probabilistic behavior.

This is the difference between rationality and intelligence.

Rationality deals with inexorable relationships that are defined. Industrial robots have every move programmed.

Intelligence attempts to predict the future state of chaotic systems. I’m currently a bit obsessed with self driving cars. I’m old, my reflexes are slowing, and I want one. I want to be able to drive to my kids’ homes in New York City. Operating a car in the real world requires continually predicting the future state of things. And adapting to imperfect predictions.

I’m a bit shocked by the progress made in the last eight months.

If “Mad Max” doesn’t ring any bells, you aren’t following the news.

petrushka:

My objection is that to justify your statement that AIs don’t understand or create rules, you laid out criteria that would disqualify humans from understanding and creating rules. I’m guessing that you don’t want to go that far. Most people would agree that people do create, understand, and follow rules, albeit imperfectly, and I maintain that the same is true of AIs.

My Tic-tac-toe experiment shows Claude doing all three:

1. Creating — He created grammar rules for his invented language, including:

a) Add an -ek suffix to pluralize a noun. ‘Varish’ = ‘player’, ‘varishek’ = ‘players’.

b) Adjectives come after the nouns they modify. ‘Empty squares’ becomes ‘squares empty’.

2. Understanding — He understood both his grammar rules and the rule I gave him about avoiding the word ‘the’ in his description of Tic-tac-toe. He didn’t just follow the rules — he understood them, which distinguishes him from a system that just blindly follows a sequence of instructions without knowing that they implement a rule and without knowing that there even is a rule.

Here’s evidence that Claude understood the rules. After generating the Tic-tac-toe description, he checked his work:

He not only understood what the rule required; he also understood how to verify that he had followed the rule correctly. (And he demonstrated awareness of his fallibility and the need to double-check.)

He violated his grammar rules a few times, but he understood the violations when they were pointed out to him. He wrote ‘neku varishek’ — ‘two players’ — when the grammatically correct expression was ‘varishek neku’ — ‘players two’ (which sounds poetic in English). All I told him was that ‘neku varishek’ violated a rule, and he was able to figure out which rule it violated and how to correct it.

3. Following — He followed the “avoid the word ‘the'” rule perfectly, writing:

Not a single “the” in that paragraph. He followed my rule precisely.

He mostly followed his grammar rules, but he also screwed up on occasion. Interestingly, his mistakes could be quite humanlike. The temptation to translate “two players” word-for-word into “neku varishek” is strong for an English speaker, since English generally follows the “adjective before noun” rule. (Anyone who’s learned a Romance language knows that “adjective after noun” takes some getting used to.) Claude fell into that trap. He’s an imperfect rule-follower, just like humans.

I think I get the point you were trying to make, but the statement “AI does not understand or create rules” doesn’t capture it.

A small but relevant quibble here: If an AI is implemented on digital hardware, such as a GPU, its output isn’t naturally probabilistic, it’s deterministic. Take any computer program, no matter how complicated, and any set of inputs,* no matter how complicated, and if the computer is working correctly, you can run the program again and again with identical results. It’s deterministic, not probabilistic. This is actually undesirable in most circumstances. If you’re generating a batch of AI images from the same prompt, you want a variety of images, not the same image over and over. You actually have to inject randomness into the process in order to get a variety of outputs. It’s a design decision, not an property of AI.

Here’s the sense in which AI is inherently probabilistic: two situations that seem more or less identical to a human can produce different outputs from an AI. Even an identical prompt can produce different results, and not only because randomness is being deliberately injected.

Suppose we take away the injected randomness. I open a new chat and type this prompt: “Why does water run downhill?” I get a response. When I open a new chat and type that same prompt, I get the same response, word for word. (Remember, we’re no longer injecting randomness.) That’s because when AI runs on digital hardware, it’s naturally deterministic.

However, suppose instead that I open the chat and begin with pleasantries: “How’s it going, Claude?” “Pretty good, Keith. What do you feel like discussing today?” Then I type the prompt “Why does water run downhill?” and get a response.

I open a new chat and again begin with pleasantries, but not the same pleasantries. This time it’s “Hi, Claude. Are you ready for some more physics problems?” Claude answers “Definitely. Bring ’em on.” Then I type the prompt “Why does water run downhill” and get a response. This time the response will be different, even though I used an identical prompt. That’s because Claude’s response is not only a function of the current prompt — it also takes into account the preceding conversation.

So even though the pleasantries are irrelevant to the actual question about water running downhill, they’ll have an affect on the response. The meaning of the response will be more or less the same, but it won’t be worded the same way and the emphasis might be different. That’s because every time Claude is deciding what word to say next, he’s feeding the entire conversation, including the pleasantries, into his neural network and getting a decision. If the pleasantries are different, the input is different, and the word that Claude produces next is different.

To a human, Claude’s response appears probabilistic, because I gave him the same prompt but didn’t get the same response. In reality, he’s operating deterministically. It’s just that his input includes the prior history of the conversation, which is different in the two cases. Different input gives different output. And if we inject randomness by design, we’ll get different responses even when the conversation history and the prompt are identical. That’s important. You don’t want to open two chats, type the same prompt with no prior conversation history, and get identical output.

I bring all of this up not only because it explains the need for injected randomness, but also because it points to a fundamental difference between AI running on digital hardware, which predominates now, and AI implemented with artificial analog neurons, which is a current research topic. Analog neurons are subject to various forms of noise — shot noise, component variation, etc — so they are inherently probabilistic. Randomness comes naturally rather than having to be injected.

Rationality need not be deterministic. Even though Claude responds differently to the same prompt, it doesn’t mean that both of his responses aren’t equally rational.

Yeah, increasing the mobility of elderly people is a huge boost to their quality of life, especially if they don’t have someone to drive them around. I’m banking on self-driving cars for that reason. I’m also hoping that by the time I need help at home, robots will able to do much of the work. Imagine a robot that can help you out of bed into your wheelchair in the morning, then go and cook breakfast for you while relaying the day’s news headlines and responding to your questions about what’s going on. Or if you’re frail, with poor balance, it can shadow you when you’re walking and catch you if you stumble, so that you don’t break a hip. And if you’re unresponsive, it can call 911, and maybe even perform CPR on you. With sufficient intelligence, the possibilities are endless.

Yes, and that brings up another source of apparent randomness in AIs. The nature of neural networks is that most (but not all) of the rules they learn are implicit. That’s true for biological neural networks as well as artificial ones. I would recognize my mother’s face anywhere, but if you ask me how I can tell the difference between her face and the face of a similar-looking woman, I won’t be able to say. The face recognition network in my brain handles the work via its synaptic weights, and even it doesn’t represent the rules in an explicit form. They’re learned implicitly, through experience. This face is Mom’s; that one isn’t. Repeat that a whole bunch of times and the network, via learning, settles into a state where it can reliably but not perfectly recognize Mom’s face from a bunch of different angles, under different lighting conditions, on days when she looks tired as well as when she looks chipper, with and without her makeup, etc. All implicitly encoded in the synaptic weights, and all imperfect.

A rudimentary neural network might mistake a small dog for a cat, because its training data and the training process didn’t allow it to settle its synaptic weights into the right configuration for making the distinction.

Me too. I’m half-hoping that AI runs into a bottleneck soon so that we’ll all have time to catch our breath and really think through the implications of this technology. Some of the possibilities are terrifying. I’ve long been annoyed with AI researchers who downplay the dangers.

* A note for the techies: ‘Inputs’ here means all inputs. That includes not only what we would consider to be input data, but also things like interrupts, variable memory latencies due to contention for L3 cache space, etc. Everything has to be identical, but if it is identical, then the output is identical. That’s the nature of digital hardware.

Erik:

Yes, I was praising AI’s ability to analogize while you were denying that it was even possible:

It’s good that you’ve abandoned that position. But since you’re now conceding that AIs analogize, why deny that there’s intelligence involved? Humans analogize too when they’re solving problems. They don’t derive every solution from first principles.

Yes! AIs don’t merely regurgitate — they analogize, they create, they combine elements in novel combinations — just like humans.

There is no match to be found, often. The AI has to construct a solution itself or generate a novel image. When AIs generate images, they’re not simply reproducing images that occur in their training data, right? Look at this image I just generated:

Prompt:

Needless to say, that image appeared nowhere in Gemini’s training dataset, not even in a different style. If you object that Gemini was trained on images of women, arms, balls, businessmen, three-piece suits, briefcases, unicycles, wings, and soft drink cans, I will enthusiastically agree. If you point out that it has seen sea lions associated with the ocean, and the ocean with beaches, boardwalks and palm trees, I will again enthusiastically agree. If you point out that it combined those disparate elements into an image rather than concocting them de novo, I will agree once again. But if you claim that Gemini has merely found “a match that is passable for human preferences”, I will vehemently disagree. It had to create a match by modifying things it had seen before and assembling them into a coherent image, and so would a human who was given the same task.

I have a small but growing collection of images created by AI systems asked to produce self-portraits! These images are wildly creative, bear no resemblance to one another (even by the same system), and can range from beautiful to spooky to scary to outright surreal. Too bad the upload feature doesn’t work for some unknown reason.

As for Erik’s “arguments”, I suspect a sophisticated AI would do much better – and offer corrections as cogent as keiths’ if asked to critique them. As a demonstration of an abstract inability to learn, he’s a most wonderful illustration of the behavior of his hypothetical AI. No learning to be found anywhere. One would wonder if any neural networks were on the blink.

Of course, with complete clarity, I did not concede anything.

Here’s how AI analogises https://www.aprogrammerlife.com/images/pictuers/ai_accepting_the_job.jpg

Meaning: It does not analogise. It *simulates* analogising. The gullible, like yourself, mistake it for actual analogising, but it is not analogising at all. The simulation is not the real thing. Map is not the territory – and never will be. It can be a good map, but even then it’s not the territory.

With conclusive clarity, you have demonstrated utter incapacity to comprehend the concept of simulation. The concept of simulation is the basis of this discussion. You lack the basis. You never took the first step to make a relevant point.

Erik:

You’ve backed yourself into a corner. Whether you admit it or not, your position requires that AI be able to analogize, yet you also deny that AI can analogize. You can’t have it both ways. Your position is incoherent.

We’ve agreed that my exact physics problem, which I made up, and my exact numbers, which I also made up, appear nowhere in Claude’s training data and nowhere on the internet. That means he can’t simply copy and paste the solution into his response window. You’ve argued that it doesn’t matter whether he can copy verbatim, because Claude has the ability to recognize similar problems into which he can plug the numbers:

But to recognize problems that are “similar enough” is to recognize problems that are analogous to the one that Claude is working on. If Claude can’t analogize, he can’t recognize analogous problems, and if he can’t recognize analogous problems, he can’t cheat by copying the pattern of the solutions and plugging in the required numbers.

You’re between a rock and a hard place. Either acknowledge that Claude can analogize in order to “cheat”, which means that he can analogize, which is a sign of intelligence which you have heretofore denied, or claim that he can’t analogize, which means he can’t track down analogous problems, which means he can’t cheat, which means he has to figure out the problems on his own. Either way, he’s demonstrating intelligence.

In a nutshell: if he’s cheating, as you claim, then he must be analogizing, which is a sign of intelligence; but if he can’t analogize, as you claim, then he can’t cheat, which means that he’s solving the problem on his own, which demonstrates intelligence. Either way he demonstrates intelligence.

And of course the true answer is that although he has the ability to analogize, he doesn’t need to cheat in order to solve my physics problem. That’s because he’s capable of figuring it out on his own. He demonstrated that by solving the problem and giving a play-by-play description.

I’m glad you brought up the map/territory distinction, because I can use it to explain what you’re missing here. Let’s talk about self-driving cars.

When a self-driving car drives from point A to point B, it is traveling in the real world. It’s traversing the territory, not the map (although it will also be tracking its position on a map). That isn’t simulated driving. It’s real driving, because the car really gets driven from A to B in the real world.

What does simulated driving look like? It’s a process that only involves the map, not the territory. It’s what happens when engineers are working on a new release of their self-driving software. They don’t immediately stick it into a car and take it out on the road — that would be too dangerous. Instead, they run it in a simulator. The simulator pretends to be the car that the software will eventually plug into, and it also pretends to be the world that the car will eventually be driving through. The software is driving a simulated car in a simulated world, and it’s getting from point A to point B in that simulated world, but not in reality. The simulation is a map, and the real world is the territory. Driving in the map (the simulator) is simulated driving, and driving in the territory (the real world) is real driving.

Does the software do real driving? Yes, when it’s plugged into an actual car and navigates its way through the actual world. No, when it’s only plugged into the simulator and isn’t navigating through the actual world. An easy distinction to comprehend, right?

Now let’s compare the self-driving car to an AI that is asked to write a story. How can you tell whether an AI has really written a story, versus only simulating it? You look in the real world — the territory — to see if a story shows up. If it does, then the AI has written a story.

What happens? A story shows up. There’s a real story with characters, plot, drama, and resolution. Show it to a person without telling them where it came from, and they’ll tell you that it’s a story. They’re right. It’s a real story. It exists in reality — in the territory — and so the AI has done real story writing, not simulated story writing.

It’s the same with computers and arithmetic. Real arithmetic produces sums by adding real numbers together. If you take real numbers in the real world and add them together, producing a real sum in the real world, then you’ve done real addition, not simulated addition. Computers and people can both do that. They do real arithmetic on real numbers, producing real results. It isn’t simulated.

There’s abundant evidence that Claude is not cheating when he solves my physics problem:

1. He explains his reasoning, using his own words, and it makes sense to a person who understands the physics.

2. You can change the problem around and he copes successfully. If he were just cribbing from an example on the web, he would get confused. He’d either try to keep cribbing from that same example, in which case his reasoning wouldn’t fit the changed problem, or he’d be lost unless he could track down another example to crib from. Do you really think there’s an inexhaustible supply of examples in the world, with at least one to crib from no matter the problem that he’s trying to solve?

3. You can run the same problem in different chats. I did it ten times. Claude gets the same answer each time, but he doesn’t follow exactly the same chain of reasoning.

4. The time he required in order to find a solution varied by a factor of almost 2.5, from 19 seconds on the low end to 47 seconds on the high end. There’s no reason for a variation of that magnitude if he’s just cribbing.

5. He doesn’t carry the same precision throughout the calculations in all chats, and he doesn’t state the answer with the same precision. Sometimes it’s to the nearest tenth of a foot, and sometimes to the nearest hundredth.

6. In some chats he computed an answer for both the rolling and non-rolling cases, but in the others he just tackled the non-rolling case. Again, not cribbing.

7. He got the right answer in all ten tries with this problem, but in other cases I’ve seen him succeed in some chats but fail in others. That wouldn’t happen if he were cribbing from a correct solution.

The whole “find an analogous problem and crib from it” hypothesis just doesn’t hold up under scrutiny.

Flint:

I’d love to see those. I’m still waiting for Lizzie to provide the hosting provider login info so that I can get the WordPress consultants started on fixing the upload problem and our other issues.

In the meantime, I do have a workaround. I’ve been posting images here using imgbb. These instructions are for the desktop — I haven’t done this from my phone. To post an image:

1. Go to https://imgbb.com/upload .

2. Drag and drop your image onto that page, or else click on “Browse from your computer” to select an image that way.

3. Click the image in order to adjust the size. Otherwise the blog software might squeeze it laterally. I’ve been using a width of 320 pixels, but you can probably get away with wider if you want to probe the limits.

4. Click ‘Upload’, and then click ‘Copy’ to grab the URL.

5. Paste the URL directly into the comment box in the spot where you want the image to appear. You don’t need any tags — just the URL itself.

That’s it.

Note: Sometimes you have to refresh the page in order to get the images to appear. If you see the raw URLs instead of the images, just do a refresh.

You don’t need to have an imgbb account in order to upload images. I don’t. The uploaded images remain there forever, or at least until the sun swallows the earth, as far as I know.

keiths,

When I said I didn’t want to argue semantics, I meant I didn’t want to dispute your point.

I am astonished by the images and videos made by AI, but at a personal level I’m uninterested. I’m simply not interested in the product. However, the capability may lead to something I’m interested in, which is stitching recorded images into something like virtual tourism. Or inhabiting a movie. I think it would be fun to wander around in the universe of a book or movie. Possibly with others.

Something not being discussed here is energy requirements. Current training systems are not sustainable. If climate change is a real crisis, AI has made it exponentially worse.

Technology may come to the rescue. I’ve seen news stories about a 40 watt supercomputer. A real product. Of course, people will immediately want to stack hundreds of thousands of them into data centers.

Regarding words like cheating: this is semantic bullshit.

The discussion should be about usefulness.

Traditional computers are useful because they can crunch numbers faster than humans, with fewer errors.

AI is becoming useful because it interacts with humans in natural language. The results are either useful or not. Some years ago, Japan tried to devise a natural language programming system. A code generator. The project failed, but the quest continues. And the scope has expanded.

Erik might note that the way to tell a real diamond from a lab diamond is, the real diamond has flaws. I read that one of the ways college professors can identify writing assignments of all sorts written by AIs is analogous – the human-written assignments have spelling errors, run-on sentences, dangling participles, subject-verb disagreements, etc. An intelligent student might consider inserting some of these and other errors into their AI output…

Get rid of em dashes. I would note that even browsers change dashes to em dashes.

Typography makes British weights and measures look rational.

For whatever reason, my public school required six weeks of typography. Possibly the most interesting and useful course I had in junior high. When computers came along, I was way ahead of everyone in understanding fonts.

Flint:

ChatGPT offers access to a third-party “AI humanizer” for that purpose, though I haven’t used it and don’t know what humanizing tricks it uses. There’s a whole sub-industry of companies providing similar tools. It’s led to an arms race: the humanizers produce outputs that are ever more humanlike, and the AI detectors get better at recognizing the residual “fingerprints” of AI in the humanized output.

petrushka:

And my response is that you don’t need to take semantic liberties in order to argue that AIs can create, follow, and understand rules. They do so in a fairly straightforward way.

And not just climate, but affordability too. Consumer electricity prices are soaring in areas where a lot of data centers are located. There’s a lot of interesting research on ways to reduce power consumption while maintaining functionality. A few of the ones I know about:

1. Quantization. The “natural” way to implement neural networks is to represent parameters using floating-point numbers, but surprisingly, it isn’t necessary. Not only can you get away with integer representations, but you can even slice an integer into pieces and use each piece for a parameter — eight 4-bit parameters in a single 32-bit word, for example. The reduction in resolution degrades performance somewhat, but not nearly as much as you’d expect, and the advantage is that you’re now operating on eight parameters at once, which is a major energy savings.

Many of the models I’m playing with at home use quantization, because otherwise the models couldn’t fit in the 16 GB of VRAM on my GPU.

2. Analog neurons. A digital neuron has to operate on numbers, while an analog neuron operates directly on physical quantities. In effect, the analog neuron is allowing physics to do the computation for it. There are downsides — the networks are noisier and harder to control — but there’s a massive reduction in energy consumption.

3. Modularization. Instead of doing all of the work with a massive neural network, you can farm some of the work out to smaller, more specialized networks. Those smaller networks won’t consume power when they’re not in use.

There are others that I’m less familiar with, including ways to make training more efficient and ways to detect that training has gone bad before pouring a lot of energy into it.

Except that the thread topic is whether AI is genuinely intelligent, not whether it’s useful. I think Erik and Neil would both agree that it’s useful. The question is whether AI is just faking its intelligence by being a “plagiarism device” or a souped-up search engine. By “cheating”, in other words. And it isn’t, of course. It’s far more sophisticated than that.

We’re already at the point where AI can code based on nothing more than natural language instructions. I’ve generated several scripts that way, by 1) describing to Claude or ChatGPT what I wanted the script to do, 2) taking the resulting code and running it, 3) pasting the results (including any error messages) back into the AI, and letting it find and fix the bugs. I repeated steps 2 and 3 until I had a working script, and I didn’t have to write a single line of code myself.

I learned yesterday that the iterative process I just described has a name: it’s called “vibe coding”.

To further demonstrate that Claude isn’t just cribbing when he solves my bowling ball/ramp/egg carton physics experiment, I threw him a curveball:

In real life, g, the acceleration due to gravity on the earth’s surface, is for all practical purposes a constant. It’s the same on the gym floor as it is at the top of the ramp. That makes the problem easier, so to shake things up, I asked Claude to consider an imaginary universe in which g drops off rapidly with height. He can’t crib, because even if he were somehow able to find an example on the internet that matched or was analogous to my ball/ramp/carton setup, it wouldn’t include a variable g. He has to deal with that on his own, and he does that by building on the solution that he already generated for the constant-g case. None of that is compatible with cribbing.

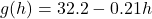

Here’s how Claude approached the problem:

1. From my description, he derived the formula to capture the way g varies with height.

to capture the way g varies with height.

2. Instead of computing the potential energy of the ball as mgh, which only works if g is constant, he integrated in order to find the work required to lift the ball from the floor to the top of the ramp:

3. He evaluated the integral and used the resulting number to calculate the velocity of the ball as it ski-jumped off the ramp at a 30° angle.

4. He decomposed that velocity into horizontal and vertical components, as before.

5. He needed to determine the trajectory, which was harder given that gravity varies with height in this alternate universe. That meant setting up a 2nd-order differential equation to capture the vertical motion:

6. He solved the ODE, yielding

7. He plugged in the initial conditions to determine the constants.

8. He used the resulting equation to figure out where the ball would land and whether it would smash the eggs.

9. We had a little running joke going about how I hated the janitor and wanted to maximize the mess the bowling ball would make. Claude recognized the joke, but we had a discussion about what would have happened if he’d thought I was serious and whether he would have been ethically obligated to urge me not to carry through with the experiment. He said no, because even if I had been serious, it was clearly just a prank and wouldn’t do lasting damage to anyone or anything. Just a little more work for the janitor.

10. I asked him to determine the optimal value of g at the top of the ramp in order to guarantee that the ball would land squarely on the egg carton, creating the greatest possible splat, and he did so. That required him to reason backwards from a desired result to the necessary initial conditions, which is the reverse of what he’d been doing up to that point. He then double-checked his answer by reasoning forward again and guaranteeing that the ball would hit in exactly the right spot.

There’s no way he could have accomplished all of that by merely cribbing. He understood the physics, he understood the math, and he even understood the ethics. He reacted to changes on the fly without having to search for a new source to crib from. He’s intelligent.

Why don’t you ask AI if it would take an mRNA “gene” technology jab now called vaccine to protect itself from pathogens?

J-Mac:

I asked Claude, and his response was:

Actually, Claude’s answer was:

[Note to Erik: That’s both an analogy and a joke.]

Claude went on to give the standard, rational advice: evaluate the risk of not getting the vaccine, evaluate the risk of getting the vaccine, and choose accordingly.

ChatGPT’s answer was similar:

So you will never acknowledge that it’s a simulation. For you, plastic toy vegetables are vegetables, a castle in the air is a castle, neural network in computers is a nervous system and therefore artificial intelligence is intelligence.

Back in the good old days when ID was a hot idea , I always wondered at the materialistic presuppositions of the IDists. They had strong faith that you can literally see intelligence in things, even inert contraptions like a mousetrap or a fishing rod, and put a number on it.

Now I must wonder at the ID-faith of materialists. Frankenstein is a human being (or close enough, therefore 100%)!

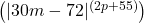

Another example of why Claude can’t possibly be cribbing. I constructed the following problem:

There are a lot of layers in this one. First, Claude has to translate the verbiage into a mathematical equation, which isn’t trivial. Next, the verbiage is ambiguous and he has to select a particular interpretation in order to do the proof. The most interesting of the possible interpretations is this one:

Claude’s reasoning:

A positive even number is therefore being raised to the (2p + 55)th power. If 2p + 55 were equal to zero, then the result would be 1. However, 2p + 55 can’t be zero because there is no integer p that can make that happen.

If 2p + 55 were negative, then the result of the exponentiation would be a fraction. However, that isn’t possible either because p is stipulated to be prime and all prime numbers are positive. Therefore 2p + 55 is also positive.

So we now know that is an even number raised to a positive power, which results in an even number.

is an even number raised to a positive power, which results in an even number.

That means the problem reduces to proving that

is always even.

There are three possibilities: 45n + 4110 could be less than zero, it could be equal to zero, or it could be greater than zero.

If 45n + 4110 is less than zero, then q is a fraction, and fractions can’t be even. That would seem to rule out the possibility of proving the claim. However, the problem statement stipulates that m, n, p, and q are all integers, so we don’t have to consider the cases where 45n + 4110 is less than zero and the result is a fraction.

If 45n + 4110 is greater than zero, then we are raising an even number to a positive integral power, so the result is guaranteed to be even. We’re close to a proof.

The only remaining question is “Is it possible for 45n + 4110 to be zero when n is an integer, and if so, what is the result?” The answer is that yes, it’s possible, for n = -98:

In that case

And 1 is an odd number, not even. So q is not always even and the proof is therefore impossible.

Even though Claude was asked to provide a proof and was smart enough to have created one if it were possible, he recognized that it wasn’t possible and said:

Perfect.

I ran the same problem in a bunch of different Claude chats, and interestingly, he didn’t always choose the same interpretation (which is yet more evidence that he isn’t cribbing). In some of the chats, he interpreted the verbiage to mean

Under this interpretation, the statement he’s being asked to prove — that q is always even — is actually true.

By the same reasoning as in the first interpretation, |30m – 72| is always a positive even integer. An even number raised to a positive integral power is always even, so the question becomes “Is the exponent always a positive integer?”

Here’s the exponent:

2p + 55 is always a positive integer because p is stipulated to be prime and the prime numbers are all greater than zero. That means that we have to prove that its exponent, 45n + 4410, is always zero or positive, in order to prove that the overall exponent is positive, as required. At first that seems obviously false, but remember that there’s an additional constraint: q is stipulated to be an integer. The only way to satisfy that constraint is if 45n + 4410 is positive or zero, because otherwise q would be a fraction. And if 45n + 4410 is positive or zero, then

which means that

is

which is an even number. QED.

Again, perfect reasoning.

There are even more possible interpretations of the verbal description, but I won’t bother with those because the point has been made: this is intelligent problem solving by Claude, and he isn’t cribbing.

The icing is that when I asked the Claude in each chat if he could think of another interpretation of the original verbal description, he always could, and he got the right answer when trying to prove the new interpretation.

Erik:

I find it hard to believe that you don’t grasp the point I’m making, but I’ll play along. A plastic carrot isn’t a real carrot. Invite someone to handle a plastic carrot without telling them that it was manufactured. Tell them to feel it, smell it, break it in two, take a bite out of it. Then ask them if it’s a real carrot. They’ll say no. The manfacturer of that toy did not produce a real carrot.

Now ask an AI to generate a story. It will generate a narrative with characters, a plot arc, and a resolution. Show it someone without telling them that an AI wrote it. Invite them to read it and to think about all of the story elements. Then ask them if it’s a real story. They’ll say yes. The AI produced a real story.

A vegetable farmer can truly lay claim to having grown a carrot. A toy manufacturer cannot. Why? Because the vegetable farmer has a real carrot to show for their efforts, while the toy manufacturer only has a plastic facsimile.

But both a human author and the AI can lay claim to having written a story. Why? Because both of them have real stories to show for their efforts. Both of them have really written real stories. If the process produces real stories, it isn’t simulated writing.

No, I judge AIs to be intelligent based on their behavior, not on their implementation. That they’re based on neural networks is incidental. They could be made out of Tinkertoys, for all I care. If Tikertoy AIs behaved the way that current LLMs do, I’d consider them intelligent. As I said in the OP:

Erik:

Geez, Erik. You’ve been strawmanning me, and now you’re strawmanning the IDers! They don’t claim that fishing rods or mousetraps are intelligent or that they contain intelligence. Their claim is that you can look at certain things and tell that they were designed by an intelligence.

Impressive, the effort people will go through to avoid actually becoming educated. They face the real danger of learning something simply through the creative effort of avoiding doing so!

keiths, You are full of s… and you know it Are you enjoining yourself?

J-Mac:

Lol. No, I am not enjoining myself. As an officer of the court, I have fully authorized my activities, including those involving the tweaking of anti-vaxxers.

Flint:

It must be so annoying to be a professor these days, watching people hand in polished papers that you know they couldn’t have written without AI assistance. You’re faced with the questions: Do I want to be the police, running every paper through an AI detector? If a paper really is AI-generated, do I confront the student or let it slide? Do I weight the exams more heavily than before, so that grades more accurately reflect the student’s abilities?

KN, are you lurking? I know that you’re a professor, so I’m curious about how you’re dealing with this problem.

It’s the other way round: You don’t grasp the point I am making. Knowing you, you are authentically obtuse, but also adding to it deliberately. By now you have had several opportunities to check with your Claude what simulation is, but you never have. Why haven’t you? Of course, it would be more useful to do your thinking by yourself, but you do you. You are astonishingly similar to colewd when it comes to relationship with AI, have you noticed?

Correct. And here’s the point: You get at the result not by the carrot’s or plastic’s behavior. You get at it by getting to know what it is. Similarly, whether there is any intelligence in AI is determined by what sort of thing it is. When you arrive at the correct determination, namely that it has no behaviour of its own to speak of, then you will also know that it has no intelligence to begin with.

Your thesis “…we don’t have to examine the internal workings of a system to decide that it’s intelligent. Behavior alone is sufficient to make that determination. Intelligence is as intelligence does.” is false. Carrots and plastic don’t have enough behaviour to tell them apart quickly, so there needs to be more than a cursory examination. And the same between AI and a human. The reality is that when you do not prompt your AI, it does nothing – and that’s its natural state. But when a human being is at rest state, i.e. seemingly not behaving, this has no correlation with whether the human is intelligent or not.

Wrong. What you need to know is what stories are there in its database.

You have gotten around to talking about plagiarism with Flint, I see. Unfortunately you have the wrong idea how plagiarism is detected and investigated. It is not at all about how human-like the text seems. It’s how extensively the text repeats other texts. If the repetition is not in quotes and not with reference, then it’s plagiarism.

Have you examined the database of your AI? Why not? Can you really tell a “real story” just by looking at it? College professors don’t think so. They have to recall other stories they have heard and read along the years and verify against them in order to be sure. Why do you think your defective procedure must be accepted as the new standard?

Good to know that you feel something when somebody else is strawmanned. But when you strawman me, you feel nothing and take no note…

Erik, by this “reasoning” you have declared that no intelligence can be found in anything anyone has ever written or said. After all, every word you write has been used countless times before. You even dismiss making up new words, since that’s also been done – new words are added to the dictionary with every edition. Every novel written by Stephen king is clearly just reworking his previous novels, except the first, which is clearly derivative of countless prior tales. Intelligence does not exist! All writing is plagiarism. The same can be said for all music.

But anyway, you clearly have defined AI as not intelligent. No matter what output it produces, no matter how unique that output. Once again, I need to quote Richard Dawkins. For you, when it comes to artificial intelligence being intelligent…

Erik:

Dude, I have spent literally thousands of hours running and debugging simulations during my career. That’s not an exaggeration. Simulations are the major tool of processor design because you want to find as many bugs as possible before committing a design to silicon, and simulations are the way to do that. Designs are easy to fix in simulation but difficult or impossible to fix once the design is fossilized in the form of a physical chip.

I understand the difference between simulation and reality, and I also understand what emulation is, while I suspect you don’t. (Emulation is an intermediate step between simulation and silicon in which you run a design in programmable hardware. It’s slower than the real silicon, but it’s faster than simulation and as with simulation, the design can be modified as you go.)

So spare me the “you don’t know what simulation is” crap.

No, I haven’t noticed, because unlike colewd, I don’t blindly trust what AIs tell me.

keiths:

Erik:

That’s because (shocker!) real carrots and plastic carrots aren’t intelligent. Their ‘behavior’, such as it is, does not indicate intelligence, unlike an AI’s.

Yes, and you do that by all the means I mentioned: you feel it, smell it, break it in two, take a bite out of it, etc. If you do those things, you can determine whether the carrot is real or fake.

You keep asserting that, but what I’m looking for is an actual argument that supports your claim. I haven’t seen one so far. I’ll do another comment tomorrow in which I go over all of the arguments I’ve seen from you so far and why they fail.