Back in 2008, Catholic philosopher Edward Feser wrote a spirited defense of classical theism and natural law theory, which made quite a splash. Although Feser’s book, The Last Superstition, was subtitled “A Refutation of the New Atheism,” it was primarily a ringing reaffirmation of teleology as a pervasive feature of the natural world – a feature highlighted in the philosophical writings of Aristotle and his medieval exponent, Thomas Aquinas. What Feser was proposing was that the modern scientific worldview, with its “mechanical” view of Nature, was a metaphysically impoverished one; that human beings have built-in goals which serve as the basis of objective ethical norms; that the existence of God could be rationally established; and that religion (specifically, the Catholic religion) is grounded in reason, rather than blind faith. Since then, Feser has authored several other books in the same vein: Aquinas: A Beginner’s Guide, Philosophy of Mind, Five Proofs for the Existence of God, Neo-Scholastic Essays, Scholastic Metaphysics, and most recently, Aristotle’s Revenge.

Until now, Feser’s skeptical critics haven’t been able to land any decisive blows, and many of those who have tried have come away with bloody noses. (The Australian philosopher Graham Oppy, who recently took part in two very civilized online debates with Feser on the existence of God [here and here], is one of the rare exceptions; Bradley Bowen, who reviewed Feser’s Five Proofs of the Existence of God three years ago, is another critic whom Feser treats with respect; Arif Ahmed, who went toe to toe with Feser on the existence of God, is a third critic who held his own against Feser.) However, Feser is now definitely on the ropes, with the publication of a new book titled, The Unnecessary Science, by Gunther Laird. The style of the book is engaging, the prose is limpidly clear, and the author possesses a rare ability to make philosophical arguments readily comprehensible to lay readers. As a further bonus, Laird is a true gentleman, whose book is refreshingly free of polemic. Throughout his book, he is highly respectful of Aristotle and Aquinas, even when he profoundly disagrees with them, and while he has occasional digs at Feser, they are lighthearted and in good humor. The scope of Laird’s book is bold and ambitious: the target of his attack is not merely the God of classical theism, but the entire Aristotelian-Thomistic enterprise of natural law theory, which he attacks on three levels: metaphysical, ethical and religious. Amazingly, despite the fact that Laird has no philosophical training beyond the baccalaureate level, he makes a very persuasive case: skeptics who read his book will come away firmly convinced that Feser has failed to prove his case, and that natural law theory needs to go back to the drawing board. And they will be right.

In this review, I’m going to discuss morality, religion and metaphysics, in that order. My review begins with chapter four of Laird’s book, titled, “Aristotelian Atrocities,” which undercuts Feser’s claim that the natural law theory espoused by Aristotle and Aquinas is the only ethical theory capable of adequately explaining why slavery, genocide and totalitarianism are objectively immoral, by showing that in fact, natural law ethics has been used to justify all manner of atrocities in the past. After that, I shall evaluate Laird’s criticisms of the faulty teleological reasoning employed in natural law ethics. Next, I’ll examine Laird’s arguments as to why natural theology (which argues for God’s existence on purely rational grounds) is incapable of boosting the credibility of miracle reports associated with a supernaturally revealed religion – in particular, the Christian religion, and why he thinks Deism is more rational than Christianity, no matter how strong the evidence for Christian miracles may be. Finally, I’ll review Laird’s penetrating criticisms of the metaphysics underlying Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy, which leads him to conclude that Feser’s case for the God of classical theism is an unconvincing one, and that Deism and atheism are viable alternatives.

INSTALMENT ONE: THE DARK SIDE OF ARISTOTELIAN-THOMISTIC NATURAL LAW ETHICS

(a) Should we trust what Aristotle and Aquinas have to say on morality?

Before we look at Laird’s telling criticisms of Aristotelian-Thomistic natural law ethics (which I’ll be doing in Instalment Two below), we might want to ask ourselves: can we trust Aristotle and Aquinas have to say on the subject of morality, in the first place? If we were to find them espousing totally outrageous or downright nutty views on morality that no reasonable person living today would accept (which Aquinas does, as I’ll show below), then that would surely cast doubt on the ethical system that they were propounding. Alternatively, if their ethical system could be used to justify atrocities (as Laird argues, with reference to both Aristotle and Aquinas), then at the very least, we would say that it was sorely lacking, and badly in need of supplementation. As we’ll see below, the case Laird makes against the two philosophers is a well-supported one, which raises troubling questions for proponents of natural law ethics.

(i) Aquinas’ ethical views: six dirty little secrets

I’m going to begin my examination of these two great thinkers with St. Thomas Aquinas, for a very simple reason: as Professor Mark Murphy freely acknowledges in his article, “The Natural Law Tradition in Ethics” in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Aquinas basically “owns” the field of natural law ethics:

If any moral theory is a theory of natural law, it is Aquinas’s. (Every introductory ethics anthology that includes material on natural law theory includes material by or about Aquinas; every encyclopedia article on natural law thought refers to Aquinas.) It would seem sensible, then, to take Aquinas’s natural law theory as the central case of a natural law position…

Another reason for starting with Aquinas is that Aristotle was, after all, a pagan philosopher who grew up in a milieu untouched by the Judeo-Christian ethic (as illustrated by his attitudes to abortion and infanticide, which I’ll discuss below). One might therefore expect that the philosophy of his medieval Christian exponent, St. Thomas Aquinas, would be largely free from the defects associated with Aristotle’s ethics. Surprisingly, however, it turns out that in certain respects, Aquinas’ ethical philosophy is much worse than Aristotle’s.

I’d like to begin by bring to readers’ attention six little-known facts about Aquinas’ philosophy, which raise very serious questions about the reliability of Aquinas’ reasoning on moral matters. Laird discusses one of these facts – Aquinas’ views on the execution of heretics – at length in his book, and he also briefly alludes to Aquinas’ views on slavery; I’m not sure if he is aware of the other facts. There are two very good reasons why so few people know about these facts: first, most Thomists don’t like to publicize them, as they’re rather embarrassing; and second, they’re pretty hard to find unless you know exactly where to look for them in Aquinas’ Summa theologiae, which might be called his theological masterpiece, although he wrote a lot of other stuff. As it happens, I first encountered the Summa theologiae more than forty years ago, so I know where the bones are buried. However, three of the facts listed below ((2), (3) and (4)) were new even to me until fairly recently, and I had to do quite a bit of digging and delving in order to uncover them. Believe me when I say that these facts are bombshells. Here goes…

(1) Aquinas on what God may justly command us to do: Modern natural law theorists such as Feser would have you believe that Aquinas taught that God can only command us to do what is reasonable and that there are certain unnatural acts that He could never command us to do, such as killing innocent people, torturing babies, having sex with a married person and taking things from other people – unlike the medieval thinker William of Ockham (c. 1287-1347), who defended the “Divine Command Theory” of ethics that defines morality as simply whatever God orders us to do, and who famously taught that God could command us to do literally anything, such as committing theft, murder or adultery, and hating our neighbor instead of loving them: these actions, said Ockham, “can even be performed meritoriously by someone on earth if they should fall under a divine command” (which at the present time, they don’t). But it turns out that Aquinas, too, taught that God could command believers to do just about anything, short of defying or hating Him: for instance, He could justly command people to kill the innocent, command a man to have sex with any woman on the planet (married or unmarried), command a man to take a second wife (but not the other way round), and command a person to take literally anything from anyone, without their permission. Why? Because every creature (people included) belongs to God, Who can dispose of things as He sees fit: in both the human and natural realms, whatever He commands is both right and natural. In Aquinas’ own words:

…[B]y the command of God, death can be inflicted on any man, guilty or innocent, without any injustice whatever. In like manner adultery is intercourse with another’s wife; who is allotted to him by the law emanating from God. Consequently intercourse with any woman, by the command of God, is neither adultery nor fornication. The same applies to theft, which is the taking of another’s property. For whatever is taken by the command of God, to Whom all things belong, is not taken against the will of its owner, whereas it is in this that theft consists. Nor is it only in human things, that whatever is commanded by God is right; but also in natural things, whatever is done by God, is, in some way, natural, as stated in the I:105:6 ad 1.

[The relevant sentence in the passage cited by Aquinas reads: “Therefore since the order of nature is given to things by God; if He does anything outside this order, it is not against nature.“]

These cases were not merely hypothetical: Aquinas explicitly declared that God had issued such commands in the past, “as when God commanded Abraham to slay his innocent son (Genesis 22:2); and when he ordered the Jews to borrow and purloin the vessels of the Egyptians (Exodus 12:35); and when He commanded Osee [Hosea] to take to himself ‘a wife of fornications’ [i.e. a promiscuous woman] (Hosea 1:2).”

Aquinas taught that God can also authorize a person to utter falsehoods, such as when Jacob tricked his blind father Isaac into giving him his special blessing before he died, by telling him that he was really his elder brother Esau (a statement which Aquinas nonetheless justified as being false in the literal sense, but true “in a mystical sense.”)

Additionally, God can even command a person to take his own life: He may have commanded Samson to do so, for instance, when he caused a Philistine temple to collapse, killing himself and 3,000 Philistines in the process; He may have also authorized the suicide of “certain holy women, who at the time of persecution took their own lives.”

Finally, God can order wholesale massacres, such as the one which the prophet Samuel commanded Saul to carry out, when he told him to exterminate the Amalekites and their property: “men and women, children and infants, cattle and sheep, camels and donkeys” (1 Samuel 15:3). Aquinas justified this order by saying that by the command of God, children could be punished for the sins of their parents, “because they are a possession of their parents, so that their parents are punished also in their person, and because this is for their good lest, should they be spared, they might imitate the sins of their parents,” while “vengeance is wrought on dumb animals … because in this way their owners are punished.” (As an aside, I note that Aquinas’ view that infants could be punished by death for the sins of their parents would also entail that they could be tortured for the same reason. Thus even torturing infants could be justified, as a punishment for their parents’ misdeeds. I might add that nowhere in his writings does Aquinas say that God cannot command acts of cruelty.)

In other words, the alleged gap between the teachings of Aquinas on what God can justly command us to do and the divine command theory of the medieval nominalist theologian William of Ockham is much smaller than Thomistic philosophers allege. (I have only been able to identify two substantive differences. First, Ockham apparently believed that it was at least logically possible for God to command us to kill and take other people’s property on a regular basis. Aquinas, on the other hand, maintained that because each of us has a natural inclination towards “preserving human life”, procreation, “the education of offspring”, and living in society, one should generally follow one’s natural inclinations in these matters, and “avoid offending those among whom one has to live” – in other words, killing, sex with your neighbor’s spouse and helping yourself to your neighbor’s property are only permissible “by the command of God” – i.e. in exceptional circumstances. For modern readers, however, the truly scandalous thing is that Aquinas believed such acts were permissible at all, and the difference of opinion between Aquinas and Ockham on this matter appears to be one of degree, rather than kind. Second, Ockham maintained that God could even command us to hate Him, if He wanted to, whereas Aquinas did not hold such a view.)

(2) Aquinas on slavery: Aquinas not only approved of slavery; he also believed that masters could beat their slaves (but not kill or mutilate them) as a form of correction. Aquinas backed up his position by approvingly citing a passage from the Catholic Bible: “Torture and fetters are for a malicious slave” (Sirach 33:28). He also viewed slaves as chattels, writing that “a slave belongs to his master, because he is his instrument” and quoting the authority of Aristotle’s Politics (Book One, Part II) in support. (Laird briefly discusses Aquinas’ views on slavery in his book; I’ll say more about this below.)

(3) Aquinas on marriage: Aquinas wholeheartedly approved of a husband beating his wife if she was guilty of fornication and had not repented of her sin (by way of comparison, I should mention that St. John Chrysostom, writing 800 years earlier, vigorously denounced domestic violence). St. Thomas Aquinas also held that a husband was perfectly justified in demanding the death penalty for an adulterous wife, in a court of law.

Regarding the “marital debt,” Aquinas held that a husband could justly demand sex from his wife at any time (so long as they were not in a public place), and that she was morally bound to comply, since the husband is given entire power over his wife’s body with regard to the marriage act (and vice versa). [To be absolutely fair, Aquinas did not authorize a husband to force himself on his wife against her wishes, but he certainly taught she should comply with his wishes at any time – and he with hers, even if she merely signals her interest in having sex, without explicitly requesting it.]

Moreover, a wife is morally bound to have sex even with a husband suffering from leprosy, if he demands it, despite the slight risk of her getting infected as a result. During sex with a leprous husband, a wife must not try to prevent conception, since it is better for a child to be brought into the world suffering from leprosy than not to be brought into the world at all.

Regarding the minimum age for marriage: Aquinas held that girls in their twelfth year and boys in their fourteenth year are capable of entering into a valid marriage and consummating it; if, however, a boy and a girl who are both mentally “capable of sufficient deliberation about marriage” get married at an even earlier age and consummate their marriage, it is “perpetually indissoluble”.

Finally, unnatural copulation with a person of the opposite sex (i.e. oral and anal sex), including one’s spouse, is, like other forms of unnatural sex (bestiality and sodomy), not only a disordered kind of lust (which is bad enough), but also a violation of the order of nature and hence “an injury … done to God, the Author of nature,” making unnatural sex even worse than adultery, seduction and rape, which are clearly “injurious to our neighbor,” but not to God. As Aquinas puts it, “a much greater inordinateness is to be found against which man commits against God” than in “sins against our neighbor.” Indeed, Aquinas even quotes St. Augustine as saying (Confessions Book III, chapter 8, para. 15) that “those offenses which be contrary to nature should be everywhere and at all times detested and punished”, and that they are so evil that entire cities have been destroyed by God for engaging in them, as were “the people of Sodom,” the city destroyed by God in Genesis 19. (For a different take on whether Aquinas viewed unnatural sex as being worse than rape, see here; for a reply, see here.)

(4) Aquinas on the State’s authority to mutilate citizens: Many Christian readers tend to associate draconian penalties such as cutting off the hand of a thief with the religion of Islam, so it may come as a shock for them to learn that Aquinas approved of the practice of mutilation, when inflicted by a public authority “as a punishment for the purpose of restraining sin.” (For further details about Aquinas’ views on coercion, see here. Interestingly, Jewish condemnation of the practice of mutilation, or “an eye for an eye,” can be found in the Babylonian Talmud, composed more than 700 years before Aquinas, in which it was argued that injuries should be compensated with money, instead.)

According to Aquinas, the State has the right to mutilate people for “lesser sins,” just as it has the authority to kill people convicted of “more heinous sins”, because every individual “belongs to the community”, of which he is a part (see here and here). Aquinas here seems to regard people as being in a very real sense the property of the State, and he even writes, “just as a city is a perfect community, so the governor of a city has perfect coercive power: wherefore he can inflict irreparable punishments such as death and mutilation.”

Nevertheless, the power of the State over the individual is not unlimited, and citizens are not obliged to obey manifestly unjust laws, or laws that go against the commandments of God, Who is Lord of all (including the State).

(5) Aquinas on torturing heretics and ex-Catholics: While Aquinas considered it utterly wrong to compel heathens and Jews to embrace the Catholic faith since “to believe depends on the will,” he insisted that members of heretical sects (i.e. Christians who reject the teachings of the Catholic Church) and apostates (or ex-Catholics) “should be submitted even to bodily compulsion” (in other words, tortured) in order to make them return to the Catholic Church, since they had already received the supernatural gift of faith at their baptism, making them members of the body of Christ (i.e. the Church), even if they were baptized as children. (Aquinas insisted that there was only one Church: the Catholic Church.) Hence people who were baptized but who no longer profess the Catholic faith may be justly compelled to “fulfill what they have promised, and hold what they, at one time, received.” When torturing heretics and apostates, Aquinas evidently considered it permissible to inflict pain, but without injuring life or limb. (See here for a detailed discussion of Aquinas’ thinking on this issue.) As he put it: “Harm is done [to] a body by striking it, yet not so as when it is maimed: since maiming destroys the body’s integrity, while a blow merely affects the sense with pain, wherefore it causes much less harm than cutting off a member.”

Aquinas also taught that heretics who refuse to retract their views after being admonished twice to repent should be “not only excommunicated but even put to death“, as soon as they are convicted of heresy. Laird has quite a lot to say on this subject, which I’ll discuss at further length below.

(6) Aquinas on God’s reprobating sinners to Hell: Aquinas held that the Beatific Vision of God in Heaven is our ultimate end, for which we have a natural desire, even though we are utterly unable to attain this end by our own efforts. However, it turns out that Aquinas was also a thoroughgoing predestinationist, who believed that God decides who will be saved and who won’t, and that the salvation of the elect is pre-ordained from all eternity, while those who aren’t pre-ordained to eternal life are certain to be damned. Election is infallible: God bestows the gift of final perseverance on those whom He has predestined, ensuring that they won’t fall away from Him in their dying moments; without this special grace, no-one can be saved. However, the grace of final perseverance is a gift we cannot merit, even by doing good works, although Aquinas elsewhere adds that those who pray for this grace “piously and perseveringly” will receive it – the catch being that in order to pray in this way, you also need grace, which God is under no obligation to give you. (Aquinas emphatically insists that God does not give us grace “because He knows beforehand that He will make good use of that grace”; rather, any good choices we make are the effect of predestination, not the cause.)

Now for the bad news: according to Aquinas, God gratuitously withholds the grace of final perseverance from the majority of people (including some people who have previously done many meritorious deeds), knowing full well that by doing so, they will fall away from Him before they die and end up being damned in Hell for all eternity, and knowing also that if He were to bestow the grace of final perseverance upon these people, they would be saved and enter Heaven. In plain English: God could easily save everyone if He wanted to, but instead He lets most people go to Hell. God’s sole motive for doing so is to manifest His tendency to punish people who fall into sin. “Yet why He chooses some for glory, and reprobates others, has no reason, except the divine will.” God can even be said to hate the people he reprobates. Even prayers won’t help these people: our prayers for others “are heard for the predestined, but not for those who are foreknown to death.” For a detailed comparison of Aquinas’ and Calvin’s views on predestination, see here.

I think most readers will agree that the foregoing views are downright nutty. One might reasonably conclude that anyone expounding such views is lacking in good sense, which raises serious questions regarding Aquinas’ credibility on moral matters. Indeed, in many respects, Aquinas’ ethical views were far worse than those of Aristotle. Since Aristotle was not a Christian and did not accept the claims of revealed religion, he would certainly have disagreed with Aquinas on points (1), (5) and (6): he did not teach that God could command people to kill their fellow human beings, sleep with their spouses or take their possessions; nor did he advocate the torture and execution of “heretics” (a term he never used), let alone the view that God reprobates most human beings to Hell. As far as I can tell, Aristotle never wrote about the punishment of mutilation, either [point (4)]. His views on women and slaves are handily summarized here in a series of short excerpts from his own writings, none of which explicitly address the morality of beating a wife or slave. As we’ll see below, however, Aristotle would have had no qualms about beating slaves, and his opinions on slavery were very seriously flawed, but it turns out that the views of Aquinas were not appreciably better.

Aquinas’ views on slavery

As Laird documents on page 170 of his book, there were a few Christian theologians (beginning with St. Gregory of Nyssa in 400 A.D.) who condemned the practice of slavery as intrinsically immoral, but Aquinas did not share their views. Instead, Aquinas regarded slavery as an unfortunate necessity in a fallen world, which would not have existed in the Garden of Eden: it was not justified by natural law, but through positive law, as a practice “devised by human reason for the benefit of human life.” Because Aquinas viewed slavery as “an undesirable necessity in a fallen world rather than a simple result of nature,” Laird considers him to have been “more advanced in morality” than Aristotle on ths issue of slavery (p. 170), but I’m not so sure. For Aquinas, the original state of nature meant “the possession of all things in common and universal freedom”; both “the distinction of possessions and slavery” were subsequently “devised by human reason for the benefit of human life.” In other words, for Aquinas, slavery is no more unnatural than private property. In addition, Aquinas, like his master Aristotle, believed that some people were natural slaves, whose deficiency in reason showed that they were meant to serve others – a practice he justified by quoting from the book of Proverbs 11:29: ‘The stupid will serve the wise’ (Commentary on Aristotle’s Politics 1.3.10). Nowhere in his writings does he condemn the practice of chattel slavery; as we saw above, his statement that “a slave belongs to his master, because he is his instrument” suggests that he approved of the practice. Finally, as we saw above, Aquinas taught that masters could lawfully beat their slaves (but not kill or mutilate them), as a form of correction. (I might add that even in ancient Rome, under the emperor Antoninus Pius, a master who killed a slave without just cause could be tried for homicide, while during the mid to late 2nd century AD it became common to allow slaves to complain of cruel or unfair treatment by their owners. Nevertheless, they were still chattels, who belonged in a different legal category from serfs.)

Elsewhere in his writings, however, Aquinas displayed genuine sensitivity towards the issue of slavery when he wrote: “Nothing is so repugnant to human nature as slavery; and, therefore, there is no greater sacrifice (except that of life), which one man can make for another, than to give himself up to bondage for the sake of that other.” (The Religious State, the Episcopate, and the Priestly Office [St. Louis, Missouri: R. Herder, 1902; translation by Fr. Procter S.T.M.], chapter 10, p. 45. See also here for a brief discussion of Aquinas’ views by Ralph Neill.)

In short: I think it is fair to conclude that Aquinas’ views on slavery are not a great improvement on Aristotle’s. Had his views continued to hold sway in the Western world, it is doubtful whether slavery would have been abolished. I might note in passing that Feser makes a damaging admission on page 147 of The Last Superstition (South Bend, Indiana: St. Augustine’s Press, 2008): “Now Aquinas himself does not have a theory of individual rights; that is a concept that only later becomes prominent in Western thought.” It was “later Scholastic philosophers,” says Feser, who developed this concept – presumably he is referring here to de Vitoria and Suarez, who vigorously opposed Spain’s attempts to apply Aristotle’s theory of natural slavery to Native Americans in the sixteenth century, teaching instead that men are naturally meant to be free – an enlightened principle which had an indirect influence on the phrasing of the American Declaration of Independence. These two thinkers were willing to differ with Aristotle on the issue of natural slavery; regrettably, Aquinas was not.

How Aquinas justified mass killings, even ones carried out in his own day

Laird makes a convincing case that the views of Aquinas could easily be used to justify mass killings, since he believed that the State has the right to kill heretics:

As he [Aquinas] wrote, “if forgers of money and other evil-doers are forthwith condemned to death by the secular authority, much more reason is there for heretics, as soon as they are convicted of heresy, to be not only excommunicated but even put to death.” Given his definition of “heretic” as one who “devises or follows false or new opinions,” Protestants and Eastern Orthodox Christians would count as “heretics” from a Catholic perspective.[3] Thus, even if the Thomist would not condone mass murder on the basis of Nazi racial theories or Communist economic plans, he might still do so on the basis of purging any subversion of the Catholic faith. Given how many billions of Protestants are scattered across the world, a Thomist regime which ruled over as many people as Hitler’s Germany, Mao’s China, or the Soviet Union might well have racked up a death toll rivaling any of those.…

This is by no means an entirely hypothetical thought exercise. During the Spanish Civil War, Catholic militias casually executed Protestants in the regions of Piedralaves and El Barraco, as Protestants were just assumed to have been allied with Communist and leftist forces.[1] The Ustashe regime which controlled Croatia and allied with Nazi Germany during World War II had an explicitly Catholic society as its ultimate goal. In the pursuit of that goal, it murdered the Orthodox population under its control with such barbarity that even its Nazi allies were shocked… These two examples… do not exactly inspire confidence in the idea that government based on “natural law” would be much more benevolent than the more materialistic regimes of the twentieth century. (pp. 193-195)

One might object that Aquinas would surely have insisted on a fair trial for any individuals accused of heresy, but Laird argues that a Thomist dictator could justify the collective slaughter of heretics, by alleging that they were subverting the collective good of society en masse, making it impractical to try each of them individually.

Laird appears to be unaware of the fact that we have an example of religious mass murder from Aquinas’ own lifetime, which he would have probably endorsed: the Albigensian Crusade (1209-1229), launched by Pope Innocent III in an attempt to eradicate the dualist heresy of the Cathars from Southern France (Languedoc). The crusade resulted in the deaths of at least 200,000 and possibly up to 1,000,000 Cathars, but failed to deliver a knockout blow against the Cathars; it was through the subsequent efforts of the Papal Inquisition that the Cathar heresy was finally eliminated from Languedoc by the first quarter of the fourteenth century. It is worth noting that Raphael Lemkin, the Polish lawyer who coined the word “genocide”, referred to the Albigensian Crusade as “one of the most conclusive cases of genocide in religious history,” while Kurt Jonassohn and Karin Solveig Björnson describe the Albigensian Crusade as “the first ideological genocide” in their book, Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations: In Comparative Perspective (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1998, p. 50), noting that “the most crucial part of any definition of genocide is that there must be intent to destroy a group” (p. 52).

Far from condemning such violence, St. Thomas Aquinas was a member of the Dominican order of monks who dedicated themselves to preaching against the Cathars and who later served as Inquistors in the Papal Inquisition which was established by Pope Gregory IX, to provide people accused of being heretics with proper legal trials, rather than subjecting them to arbitrary mob violence. Catholic scholar Michael Novak makes an unconvincing attempt to exonerate Aquinas in his article, “Aquinas and the Heretics” (First Things, December 1995), arguing that heresy “directly undercut kingly power” as kings claimed to rule in the name of God and His Church, that “thirteenth-century societies were highly fragile” and that “[t]he time was not yet ripe for the impulses of modernity” – all of which explains why “heresy was perceived as the primal threat to social order, both by ecclesiastics and by secular rulers.” But Novak’s argument presupposes the legitimacy of a “Christian state,” which is precisely what needs to be established. It is worth noting here that the first Christian Emperor of Rome, Constantine the Great, and his Eastern counterpart Licinius, issued the Edict of Milan in 313 A.D., giving Christianity legal status and freedom from persecution, but without making it the state church of the Roman Empire. The Edict of Milan was a very enlightened document for its time, granting toleration to all religions: “[W]e have also conceded to other religions the right of open and free observance of their worship for the sake of the peace of our times, that each one may have the free opportunity to worship as he pleases; this regulation is made that we may not seem to detract from any dignity of any religion.” Forty-nine years later, Rome’s last pagan emperor, Julian the Apostate, issued a new edict that recognized all forms of Christianity, as well as Judaism and paganism, across the empire.

The first State where Christianity was the official religion was established not by Constantine the Great (as popularly thought) but by the Roman Emperor Theodosius the Great in his Edict of Thessalonica of 380 A.D., under the influence of Pope Damasus I. From the outset, it was intolerant: in 383 A.D., heretics were officially forbidden to hold meetings, ordain priests or promulgate their beliefs. Aquinas, who lived his entire life in a medieval Christian state, never questioned this State-sanctioned religious intolerance: nowhere in his writings do we find him debating whether Constantine’s pluralist vision of an ideal State was preferable to that of Theodosius. By contrast, the medieval thinker William of Ockham, whom Feser frequently faults for his nominalism (putting him at odds with Aquinas), held a much more enlightened view on the issue of free speech, putting him ahead of his time.

Novak also attempts to whitewash the harsh views of St. Thomas Aquinas by claiming, incorrectly, that for Aquinas, a heretic meant “a person of Catholic faith who deliberately and resolutely, even after having been called to reflect on the matter, has chosen to renounce that faith in some important particular.” No; that’s what the word “apostate” means. The term “heretic” is used by Aquinas for Christians who corrupt the Catholic faith. Aquinas also regarded adults who had been brought up as non-Catholics since childhood as guilty of heresy, even though they had never belonged to the Catholic Church and had therefore never turned away from it. His reasoning was that insofar as these people despise the Catholic faith, or refuse to listen to it being preached, they are guilty of the sin of unbelief, since “it is part of human nature that man’s mind should not thwart his inner instinct, and the outward preaching of the truth.” In other words, once you’ve been exposed to the Catholic faith, if you then scornfully reject it, then you are morally blameworthy, because in doing so, you are rejecting the God-given promptings of your heart to embrace it. In such cases, “the will’s contempt causes the intellect’s dissent”. This sin of unbelief arises from pride. The only heretics whom Aquinas would have excused for their lack of belief were “those who have heard nothing about the faith.” The Cathars living in thirteenth-century Languedoc had been exposed to plenty of Catholic preaching by Cistercian monks and later, by Dominican friars; they were therefore without excuse.

Aquinas also explicitly justified religious warfare, writing that “Christ’s faithful often wage war with unbelievers, not indeed for the purpose of forcing them to believe, because even if they were to conquer them, and take them prisoners, they should still leave them free to believe, if they will, but in order to prevent them from hindering the faith of Christ… by their blasphemies, or by their evil persuasions, or even by their open persecutions.” In this passage, the unbelievers he is talking about are those “who have never received the faith, such as the heathens and the Jews: and these are by no means to be compelled to the faith,” since faith could not be coerced. Heretics, on the other hand, could be justly compelled to return to the faith they had once received. Aquinas taught that all Christians receive this faith at their baptism, since the baptism even of a child of unbelievers is sufficient to bestow on that child the gift of supernatural faith, making that child a member of the Church. (Recall that for Aquinas, there is only one Church: the Catholic Church.) Since Aquinas favors dealing with heretics even more harshly than with heathens and Jews, it follows that he would have also approved of a religious war against heretics who were “hindering the faith of Christ … by their evil persuasions.” Aquinas was particularly harsh in his criticisms of the Cathars, referring to them disparagingly as “the Manichees, who, in matters of faith, err even more than heathens do.” We may therefore legitimately surmise that he would have wholeheartedly supported the Albigensian Crusade, which was provoked by the alleged murder of a papal legate by Count Raymond of Toulouse, who was sympathetic to Catharism. As we have seen, that Crusade killed at least 200,000 people. By any account, that’s an atrocity.

There can be no reasonable doubt, then, that Aquinas approved of wholesale mass killings, if they were deemed necessary in order to protect the Catholic faith.

If the ethical views of Aquinas sound unacceptably extreme, what about those of Aristotle?

(ii) Aristotle’s ethical deficiencies

Feser on philosophy’s 700-year downhill slide since the abandonment of Aristotle

Laird has done his own research on Aristotle, and what he has turned up will undoubtedly raise some eyebrows among his readers. He begins by quoting from an over-the-top passage in Feser’s book, The Last Superstition (South Bend, Indiana: St. Augustine’s Press, 2008) lamenting the decline of Aristotle’s philosophy (the italics, which I’ve also bolded, are Feser’s):

Abandoning Aristotelianism, as the founders of modern philosophy did, was the single greatest mistake ever made in the history of Western thought.… It is implicated in the disintegration of confidence in the rational justifiability of morality and religious belief… and in the intellectual and practical depersonalization of man that all of this has entailed, and which in turn led to mass-murder on a scale unparalleled in human history. (2008, p. 51)

Later, on page 222, Feser denounces the attempt to discredit Aristotelianism (beginning with William of Ockham in the fourteenth century and the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth) as a “centuries-long scam” which has “pulverized the intellectual foundations, not only of religion, but of any possible morality,” leading to “a debasement of man the most brutal realizations of which were National Socialism and Marxism,” not to mention Western consumerism and reductionism. On page 213, Feser further contends that currently fashionable subjectivist theories of morality (such as Hume’s) are inadequate to ground our general “horror of slavery,” whereas a natural law theory of morality entails “a right to personal liberty that is strong enough to rule out chattel slavery as intrinsically immoral” (p. 147). The claim made by some writers that natural law theory would support “slavery as it was known in the United States” is dismissed by Feser as “a slander” (p. 147); at the very most, the only forms of slavery that natural law theory could possibly countenance are being forced to work to pay off a debt, or as a punishment for a crime (p. 283). In short: if you love freedom and loathe slavery, Nazism and Communism, you should welcome Aristotle’s and Aquinas’ theory of natural law with open arms.

Laird’s surprising findings, in a nutshell

Laird turns the tables on Feser, by quoting from a wealth of sources which demonstrate that Aristotelianism provides no inherent condemnation of racial chattel slavery, and that Aristotle’s teachings actually helped provide a theoretical justification for the practice of slavery in the American South, despite the fact that Aristotle himself said absolutely nothing on the subject of race in his writings on slavery. Laird also marshals documentary evidence showing that in Hitler’s Germany, Nazi philosophers such as Hans Friedrich Karl Guenther enthusiastically embraced the writings of Aristotle’s teacher, Plato, even if they were less enamored of Aristotle himself. The Nazis strongly identified with Plato’s theory that people could be divided into various types, although Plato himself didn’t envisage these types in racial terms. To make matters worse, Laird demonstrates that Karl Marx’s Communism was heavily Aristotelian in its teleology; where he differed from the Stagirite was in his conception of human good. Finally, it turns out that Aristotle approved of infanticide for eugenic reasons. If Laird is right, then natural law theory is not much of a bulwark against human rights abuses. Something more is needed. But first, we need to ask: how well do Laird’s historical claims stack up? Surprisingly well, as we’ll see.

Aristotle’s views on slavery

Let us begin with the issue of slavery. Even a cursory reading of Aristotle‘s Politics (Book One, parts IV and V) reveals that he viewed a slave as “a living possession” who “wholly belongs” to his master, concluding: “It is clear, then, that some men are by nature free, and others slaves, and that for these latter slavery is both expedient and right.” Thus “from the hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others for rule.” Although slaves (unlike animals) were at least capable of recognizing reason [logos] in another, even if they were incapable of exercising it themselves, Aristotle maintains that “the use made of slaves and of tame animals is not very different.” Aristotle envisaged the master of a household as governing like a benevolent king when wielding authority over his wife and children, but like a despot when issuing orders to his slaves: the authority he wields is primarily to advance his own interests, rather than that of his slaves. It is important to note that Aristotle did not believe that there was any physical characteristic identifying people as natural slaves; nevertheless, his views on “natural slaves” were eagerly appropriated by Southern slaveholders in the nineteenth century. Rather than quoting from Laird’s extensive sources, I shall content myself with quoting the conclusion reached by the late Mavis C. Campbell (d. 2019), formerly Professor Emerita of history at Amherst College, Massachusetts, in her 1974 study, Aristotle and Black Slavery: A Study in Race Prejudice (Race XV, 3: 283-301):

Aristotle, in fact, had a tremendous impact on Black slavery, and he, perhaps second only to the Bible, was one of the chief sources to be quoted in the defence of slavery both by European clerics and philosophers as well as by slave masters and educators of the South.

Campbell documents how Aristotle’s theory of the natural slave was appealed to in the sixteenth century, when Spanish explorers discovered the New World and found it to be peopled with native Americans. Many theologians argued that the native Americans were “natural slaves.” But what was more disturbing was that even Spanish advocates who opposed the enslavement of the native Americans, such as the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas, owned Black slaves and passionately defended the practice of enslaving Africans. (To be fair, I should point out that Las Casas repented of advocating this practice later in life, but by then the damage had already been done: the first 4,000 African slaves were shipped to Jamaica as early as 1518, on the order of King Charles I of Spain.)

Finally, it is worth noting that leading antislavery campaigners such as Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746), one of the founding fathers of the Scottish Enlightenment and a highly respected moral philosopher in eighteenth-century North America, vigorously opposed Aristotle’s defense of slavery. In his System of Moral Philosophy (Vol I, Chapter V, p. 301), published in 1755, Hutcheson forthrightly declares, “[N]o endowments, natural or acquired, can give a perfect right to assume power over others, without their consent. This is intended against the doctrine of Aristotle, and some others of the ancients, ‘that some men are naturally slaves’ … The natural sense of justice and humanity abhors the thought.”

The Nazis and their strange love affair with Plato

I won’t say much about the Nazis’ appropriation of Plato’s philosophy, except to briefly quote what Laird says about Hans Friedrich Karl Guenther, who was “arguably the father of academic ‘race science’ inside Nazi Germany” (p. 180):

If the [Nazi] party thought Guenther was the father of race science, Guenther thought Plato was its grandfather. He wrote an entire book titled Platon als Hueter des Lebens, or Plato: The Guardian of Life, praising the classical philosopher for being so conscious of “the laws of heredity and selection;” Guenther explicitly called Plato a precursor of “Gobineau, Mendel, and Galton” (whose ideas Guenther utilized to justify his theories of Nordic supremacy) and a clear-sighted proponent of the doctrine of human inequality. Looking at Plato’s segregation of human souls into gold, silver, and bronze, Guenther believed the philosopher was anticipating Nazi theories of racial difference, the highest type of human naturally being Nordic, and of course, the only type worthy of both ruling and doing philosophy.[2]

In this way as well, Guenther found in Plato a staunch defender of Nazi eugenics.

The reader might be wondering whether Plato actually espoused the views that the Nazis ascribed to him. In an essay titled, Distinction Without a Difference? Race and Genos in Plato (Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, 2002), Professor Rachana Kamtekar of Cornell University acknowledges that Plato (like modern-day racists) classified people into various types. For Plato, a person’s type or genos comprises his ancestors and descendants, his ethnic group. There’s also a special genos for males, females, androgynous individuals, lesbians and people who are “entirely masculine.” Kamtekar also points out that Plato also subscribed to “ethnic stereotypes about such groups as the Thracians, Phoenicians, and Egyptians.” However, she argues that “even though he subscribes to various ethnic stereotypes, Plato does not posit a natural link between ethnicity and virtue,” and concludes that “while there is no conceptual impossibility in Plato’s having views about race, he considers moral distinctions between people more significant than ethnic ones – although the two might be related.”

More than two millennia after Plato, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the various human races were widely believed to correspond to different types of human beings, having different degrees of virtue – a notion popularized by thinkers such as Arthur de Gobineau, author of An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races, which was popular with Nazi ideologues as well as American white supremacists.

The purpose of this story is not to discredit Plato, but to show that that the Platonic doctrine of essentialism (espoused in a modified form by Aristotle) can be used for ill as well as good: to enslave as well as liberate. Great care must therefore be taken when defining the true nature of any kind of being – especially when the being we are dealing with is rational – or enormous social harms may follow.

Marx and his intellectual links to Aristotle: the role of teleology

While reading Laird’s book, it came as a shock for me to learn that Marx was a great fan of Aristotle, as Feser himself acknowledges in an blog article titled, “Adventures in the Old Atheism, Part IV: Marx” (January 23, 2020), whose argument Laird summarizes as follows:

While noting that Marx, unlike Aristotle, was an atheist and a materialist, Feser admits that he did believe (as do some contemporary atheists like Thomas Nagel) in a naturalistic sort of teleology. Marx thought that “material systems reliably exhibit tendencies toward certain outcomes, and that identifying the outcome toward which a component of the system aims or for the sake of which it operates is a crucial part of explaining it.” Additionally, Marx seemed to have shared Aristotle’s ideas of what constituted a good life, which naturally informed his beliefs on proper social organization. Feser quotes the scholar Allen Wood, who said “the good life, for both Marx and Aristotle, consists chiefly in the actualization of one’s powers.” Now, as Feser immediately notes, Marx placed too much emphasis on economics in his assessment of the human Essence and its corresponding good (or actualization), and Marx’s economics were quite dubious anyways.[1] But this would not make Marx some sort of anti-Aristotelian, and it is no proof he attempted to either refute or abandon Aristotelianism. (pp. 185-186)

The reader might ask: what about the grave human rights abuses arising from Marx’s ideology? Aren’t these fundamentally at odds with Aristotle’s teachings? Laird responds that while the abuses produced by Marxist-Leninism may well be at odds with Aristotle’s political philosophy, they in no way contradict his underlying metaphysics, with its heavy emphasis on teleology:

Feser would and does claim that Marx’s “economic reductionism, vision of human life as a struggle of antagonistic classes, [and] hostility to the family… are all repulsive and inhuman,” and such errors contributed to if not caused the various atrocities Communist regimes were known for.[1] That may be true, but it is also irrelevant to Aristotelianism. Nothing in Aristotelian metaphysics inherently or necessarily denies class struggle, the belief that the family is useless or outrightly harmful to economic justice, or whatever. You could say that anyone who holds such positions has gravely misunderstood the Essence of Humanity and its associated telos, but you could not say they are outrightly denying that such things exist at all. Thus, it seems that Feser was simply wrong to ascribe Communism’s death toll to any “refutation” or “abandonment” of Aristotelianism. (pp. 187-188)

The inescapable conclusion that we are driven to accept is that the ethical systems of both Aristotle and Aquinas can be used to justify wholesale massacres: the former, on a faulty conception of human ends (such as that of Karl Marx); and the latter, on religious grounds (i.e. the protection of faith in a Christian State).

In all fairness, however, I should point out that while Aristotle envisaged the individual as being a part of the State, he certainly did not view each citizen as a mere cog in the wheel of society, as Karl Marx did. Aristotle’s own political views appear to have been fairly moderate, and far removed from the totalitarian ideologies of Marxist-Leninism and Nazism (see here for further details).

Aristotle on infanticide

I have left until last the most odious element of Aristotle’s philosophy, which Laird discusses on pages 159 to 163 of his book: his approval of infanticide not only for eugenic reasons, but also in cases where parents felt they had too many children. Lest I be accused of misrepresenting Aristotle’s views, I shall content myself with quoting the concluding paragraph of Dr. Gerrit Van Niekerk Viljoen’s excellently researched paper, Plato and Aristotle on the Exposure of Infants at Athens (Acta Classica 2 (1959): 58-69).

In the case of deformed new-born infants, Aristotle recommends exposure without giving any indication of any public opinion opposed to this kind of exposure; in the case of excess procreations he personally by implication, apparently, also considered exposure a suitable means of limitation, bur as he was conscious of a general or at any rate widely spread public opinion against this kind of exposure, he recommends a limitation of the maximum number of procreations, coupled with early abortion, as substitutes for exposure in communities where the public opinion is so opposed to it.

Needless to say, Aristotle’s medieval Christian exponent, St. Thomas Aquinas, would have forcefully disagreed with his master’s views on this issue: for Aquinas, infanticide of this kind was tantamount to murder. But as we saw above, Aquinas had no qualms about the killing of innocent children, at God’s command (such as the children of the Amalekites), since “by the command of God, death can be inflicted on any man, guilty or innocent, without any injustice whatever.”

The results of our investigation should now be clear: the system of natural law ethics developed by Aristotle and Aquinas has gaping holes in it, making it vulnerable to all sorts of abuses and atrocities. Is there anything that can be done to remedy these deficiencies?

(b) Why a teleological view of human nature is not enough to protect us from human rights atrocities

One conclusion which has emerged from the foregoing discussion is that merely having a deeply teleological view of human nature does nothing to prevent a society from engaging in mass atrocities and horrific human rights abuses. In particular, it fails to prevent abuses inflicted on individuals in order to benefit the State. Moreover, it fails to rule out the possibility of chattel slavery, where one individual owns another individual. It also fails to guarantee human equality – especially, racial and sexual equality. Finally, it fails to exclude religious atrocities. How can we remedy these hideous defects?

Abuses inflicted by the State on individuals are typically justified by appealing to the “greater good” of the community, of which each individual is merely viewed as a part: a cell or organ in the body politic (pictured above). As Aquinas put it in his Summa Contra Gentiles (Book Three, Part II, Chapter 146): “Now the physician quite properly and beneficially cuts off a diseased organ if the corruption of the body is threatened because of it. Therefore, the ruler of a state executes pestiferous men justly and sinlessly, in order that the peace of the state may not be disturbed.” If the relationship of the individual to the State is viewed as being like a cell’s or an organ’s relationship to the body, the potential for human rights violations is enormous. In his book, Neo-Scholastic Essays (South Bend, Indiana: St. Augustine’s Press, 2015), Feser refers to what he calls the principle of totality (2015, p. 399), which Laird aptly summarizes as follows: “This principle states that it is occasionally morally licit for a rational creature to frustrate the final causes of one of its body parts or faculties, or even annihilate them (which would otherwise be very bad) if doing so is necessary to preserve the health of the whole organism” (p. 160). And if people are viewed as parts of the body politic (as both Aristotle and Aquinas maintained), then the conclusion that they may be justly eliminated if they are judged to pose a danger to society seems inescapable. One might ask: what kind of danger would such people need to pose, in order to warrant their elimination? Exponents of natural law ethics have differing views on this matter: as we have seen, Aquinas thought that simply being a heretic was enough to make anyone a menace to society. As for Aristotle, Laird argues convincingly that he justified the practice of direct infanticide by appealing to the Principle of Totality. For instance, writes Laird, “[i]f a child were born with Down’s Syndrome or some other severe defect, he or she would be a drain on the resources available to the community while offering very little to help them survive” (p. 161). As Feser himself acknowledges, Plato and Aristotle “did not condemn infanticide when done for eugenic reasons.”

It seems to me that a philosophically robust version of individualism is the only proper antidote that can prevent violence in the name of “the greater good” of society. For the vital metaphysical truth that individualists grasp is that individuals do not exist for the sake of society; rather, society exists for the sake of enabling individuals to pursue what is good for them. The reason why society does not own individuals is that the good of human individuals is logically prior to that of society: in order to understand what is good for society, one has to know first what’s good for human beings. The relationship of organs to a body is the other way round: one first has to understand what it means for a body to be healthy, before one can understand what’s good for a bodily organ. Hence it is illicit to appeal to the Principle of Totality in order to justify the subversion of individual rights to the good of the State.

I am, of course, well aware that a strong case can be made for the execution of individuals whose very existence poses a threat to the life of the community in which they live – for instance, notorious gang lords who are too powerful to be safely imprisoned. However, the justification for the execution of these criminals does not depend on an appeal to the Principle of Totality, but rather, to the right of any community to defend itself against a mortal threat.

We have also seen that a teleological view of human nature, by itself, is incapable of resolving the question of whether it is possible for one human being to own another, as occurs in chattel slavery. To exclude this possibility, we need a concept of “human being” which makes it clear that people cannot be owned by anyone, and that each person is an “end-in-itself.” However, this concept of the human person comes to us not from Aristotle, but Immanuel Kant – a philosopher whom Feser breezily dismisses in The Last Superstition as “possibly a bigger disaster than Descartes and Hume put together” (2008, p. 217), denigrating his Categorical Imperative as “a notoriously useless test for determining how one should act” (2008, p. 218 – see here for a more balanced discussion of Kant’s views by the philosopher Christine Korsgaard), without even mentioning its underlying concept of the human person as an end-in-itself. Feser faults Kant for denying that we can ever know the objective natures of things, but to give credit where credit is due, one thing Kant is quite clear about in his writings is that rational beings such as ourselves belong to a moral community, and that our being rational entails our having certain obligations towards one another. (Aquinas himself said something similar: as rational beings with a natural inclination to live in society, we should avoid offending the people among whom we have to to live.) Kantian ethics, whatever one may think of it, is not something to be sneezed at: Kant is one of the very few philosophers who really had something original to say on the subject. I might also recommend, in passing, Joe Molony’s excellent article, A Moral Investigation of Torture in the Post 9.11 World (Undergraduate Review, 6 [2010], 132-138), which makes a powerful case against torture on Kantian grounds. Historically speaking, the abolition of practices such as torture, mutilation and judicial corporal punishment is principally due to the influence of the Enlightenment, with the Italian jurist Cesare Beccaria deserving special mention. (Beccaria’s work was not well-received within the Catholic Church: it was placed on the Roman Index of Forbidden Books, on account of its philosophical and doctrinal errors.)

Another failing of natural law ethics is that none of its tenets are incompatible with racism and sexism. How might one remedy this deficiency? It might seem that it would be sufficient to point out that all humans share a common nature as rational animals, but a racist or sexist could reply that certain types of humans realize the human ideal of rationality to a greater degree than others, justifying the existence of a racial hierarchy or patriarchy. Assistant Professor Oludamini Ogunnaike, in his highly illuminating study, From Heathen to Sub-Human: A Genealogy of the Influence of the Decline of Religion on the Rise of Modern Racism (Open Theology 2016; 2: 785–803), contends that “modern racism, defined here as racial essentialism coupled with a hierarchal ranking of races, is a phenomenon that appears to have arisen only in postEnlightenment Europe.” As he explains it: “Racial essentialism developed from the 17th century division of humanity into races and Kant’s theory of inherited racial identity; and the ranking of races was a direct result of a particular transformation of the hierarchical cosmology of the chain of being.” What needs to be rejected, then, is the notion that subsets of humankind (e.g. this or that race) can have their own distinctive “essence” which defines them. Essentialism at anything below the species level is ethically pernicious.

Ogunnaike is also highly distrustful of the Aristotelian attempt to define our common humanity in terms of reason, rather than intellect – by which he means “a divine, sometimes uncreated, faculty of human beings through which they directly perceive God and divine truths.” Ogunnaike dates this exaltation of reason in European philosophy to the late 13th century, when Aristotle’s philosophy became dominant, and charts the unfortunate course of its development: “Whereas in the Middle Ages, humanity was judged by participation in or proximity to a transcendent spiritual, Divine ideal (Christ or God), the secularization process of the early Modern Period and the Enlightenment resulted in humanity being judged by proximity to the immanent ideal of rational, enlightened European man.” What makes all races and sexes of human beings equal, then, is their openness to the Infinite.

I imagine that Laird (who is an atheist agnostic) would probably object to Ogunnaike’s definition of what it means to be human. Nevertheless, even non-religious people can appreciate the general point he is making: namely, that the bold, rational enterprise of understanding Nature scientifically is, despite its impressive accomplishments, a limited one, yielding only a finite scale of inherent moral value. If we want to affirm that each and every human being is of infinite value as an “end-in-themsleves”, then defining our humanity in terms of this rational enterprise runs the danger of putting us all in a box, where some individuals are bigger and more important than others: thinkers like Newton and Einstein, for instance. What makes us humans special, however, is the fact that we can all dream about what’s outside the box. The human mind is bigger than any rational enterprise.

Sexism is a much tougher ethical nut to crack than racism. For while the proposition that the various human races represent different types of human beings is indefensible both scientifically and morally, it seems very plausible to maintain that men and women are different types of human beings, even if their characteristics overlap to a greater degree than was once believed. Is a “complementarian” view of the sexes consistent with a belief in their equality? Of course; but the problem here is that it is also consistent with the contrary belief: that one sex is meant to rule and the other to serve. (Aquinas, for example, notoriously held that “woman is naturally subject to man, because in man the discretion of reason predominates,” and that even in the state of innocence (Eden), “there would have been some inequality, at least as regards sex”.) One way to block this insidious slide into sexual inequality would be to assert that the two sexes are not only complementary, but also inter-dependent, making it impossible to justify the subjection of one to the other. [There are, of course, human individuals who don’t fit neatly into either of “the two sexes,” but that is another issue.] The only logically consistent alternative to this doctrine of mutual inter-dependence, it seems, is to reject sexual essentialism root and branch, and to assert that sex is infinitely malleable: it is whatever we choose to make it. Once we go down that path, however, we have to follow it to its logical conclusion: transhumanism. Why should we not remake our human biology as well? And why should I not be able to surgically resculpt my face to make it look like that of a wolf, if I so choose? For many, however, including myself, such scenarios constitute an ethical reductio ad absurdum. In the sexual arena, then, typology appears ineliminable, but the “types” in question rely upon one another.

How the Divine Ownership Principle renders Aquinas’ ethical views more toxic than those of Aristotle

I have said enough about the failings of Aristotle’s ethical views. The theological views of Aquinas – in particular, his extreme views on what God could justly command us to do – make his ethical system even more toxic than Aristotle’s, because Aquinas believed that God owns us: as he put it in a discussion about angels, “every creature in regard to its entire being naturally belongs to God.” Henceforth, I’ll refer to this claim as the Divine Ownership Principle. Being a devout Catholic, Aquinas would have insisted that people should not believe in any alleged private revelations from God (such as a command to kill someone) unless they are approved by the Church, but that’s hardly the point; what matters is that Aquinas, as we saw above, taught that God could command, and at times has commanded, actions that completely overturn Aristotelian natural law – which he justified by arguing that “whatever is done by God, is, in some way, natural.” I have already drawn attention to Aquinas says about the massacre of the Amalekites (pictured above; print from the Phillip Medhurst Collection of Bible illustrations), in which God, speaking through the prophet Samuel, commanded the massacre of innocent women, children and even animals. The reader might respond by saying, “Well, that was an incident in the dim and distant past, if indeed it happened at all.” Not so. It turns out that the Biblical accounts in which God commands the slaughter of entire populations were repeatedly invoked by Christians at various times in history, in order to “justify” acts of conquest abroad. Graduate student Anthony Rimell, of the University of Auckland, New Zealand, in a paper entitled, Origen on Conquering ourselves: Reclaiming the Conquest Texts, describes how the Biblical texts from the book of Joshua, describing the conquest of the land of Canaan, were subsequently used by the Spanish to justify the conquest of the New World, by the Puritans when establishing the settlement of “New Canaan” in Connecticut, and by the the Boers in South Africa. Curiously, according to Rimell, the Biblical Conquest narratives were invoked not only by the Europeans who occupied New Zealand, but also by a Maori Chieftain resisting European occupation!

The moral of the story is that any system of ethics which makes human beings the property of their Creator is vulnerable to abuse, because it gives them a theological license to treat people as property (or as Kant would say, as means rather than ends), when God commands it. The only way to prevent such abuse is to either radically reconstrue people’s relationship to their Creator by insisting that we are not God’s slaves but His beloved children, or to do away with revealed religion altogether. Laird would of course suggest the latter course. But in either case, it is the Divine Ownership Principle which we need to reject, root and branch, as it is ethically corrupting.

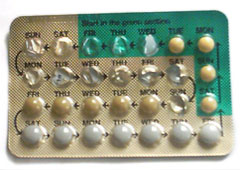

(c) Contraception and abortion: what can God command us to do? A reductio ad absurdum for Aquinas’ ethics

Here’s a final question to consider: according to Aquinas, could God command someone to intentionally abort a child, or to use contraceptives? These are both actions which the Catholic Church (and many other Christian churches) condemn as “intrinsically evil” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, para. 2370). However, it seems that the answer Aquinas would have to give to this question is YES. For as we saw above, Aquinas allowed that God could command a person to take their own life: a profoundly unnatural act if ever there was one, “because everything naturally loves itself, the result being that everything naturally keeps itself in being, and resists corruptions so far as it can.” Nevertheless Aquinas, quoting St. Augustine (City of God Book I, chapter 21), was prepared to allow that the Holy Ghost may have commanded Samson and “certain holy women, who at the time of persecution took their own lives, and who are commemorated by the Church” to commit suicide. Furthermore, Aquinas also insisted that God could order the slaughter of innocent children (such as the children of the Amalekites), since “by the command of God, death can be inflicted on any man, guilty or innocent, without any injustice whatever.” A God Who can command suicide and infanticide can certainly command abortion. (I might add that some of the Amalekite women slain by the Israelites would undoubtedly have been pregnant; if they were stabbed through the belly, that would be a clear-cut case of abortion.) And a God Who can command someone to carry out an abortion can also command them to use contraceptives, as this is a lesser violation of the natural law than abortion, which takes a human life.

This is surely a farcical reductio ad absurdum of Aquinas’ ethical theory: on the one hand, he opposes abortion and contraception as utterly abominable practices which are contrary to natural law (and, in the case of abortion, homicidal), but his own theory entails that God could command such abominations. The most logical way to salvage his theory is to get rid of the Divine Ownership Principle, which I discussed above: the pernicious notion that God owns us as property. Eliminate that premise, and we can have a rational discussion about ethics once more. It is not a premise we find in Aristotle, whose God [the Unmoved Mover] takes no interest in human affairs. It is a theological premise, based on a flawed concept of God’s relationship to us. (One could, if one wished, argue for a contrary position on theological grounds: God, in freely choosing to become our Father, willingly accepted the responsibilities of a father: to protect His offspring and promote their welfare, while respecting their freedom as persons endowed with reason and free will – which means that He could never order anyone to kill another innocent human being, any more than a father can order a son to kill his brother.)

It is interesting to speculate what Aristotle would have to say to his medieval exponent, St. Thomas Aquinas, if the two could be miraculously resurrected. My guess is that he would point an accusing finger and say to him, “You call yourself my disciple? How dare you distort my teachings!” And as we’ll see below, Laird documents many other ways in which Aquinas distorts the teachings of Aristotle, when discussing religion and morality.

Coming up in the next instalment of my review of Laird’s new book, The Unnecessary Science:

INSTALMENT TWO: DO NATURAL LAW ARGUMENTS ON SEXUAL ETHICS ACTUALLY WORK?

================================================================================

APPENDIX: Aristotle’s views on slavery and his influence on the institution of New World slavery in the sixteenth century and American slavery in the nineteenth century

Let us begin with what Aristotle had to say on the subject of slavery in his Politics (Book One, parts IV and V; translated by Benjamin Jowett):

The master is only the master of the slave; he does not belong to him, whereas the slave is not only the slave of his master, but wholly belongs to him. Hence we see what is the nature and office of a slave; he who is by nature not his own but another’s man, is by nature a slave; and he may be said to be another’s man who, being a human being, is also a possession. And a possession may be defined as an instrument of action, separable from the possessor.

But is there any one thus intended by nature to be a slave, and for whom such a condition is expedient and right, or rather is not all slavery a violation of nature?

There is no difficulty in answering this question, on grounds both of reason and of fact. For that some should rule and others be ruled is a thing not only necessary, but expedient; from the hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others for rule…

Where then there is such a difference as that between soul and body, or between men and animals (as in the case of those whose business is to use their body, and who can do nothing better), the lower sort are by nature slaves, and it is better for them as for all inferiors that they should be under the rule of a master. For he who can be, and therefore is, another’s and he who participates in rational principle enough to apprehend, but not to have, such a principle, is a slave by nature. Whereas the lower animals cannot even apprehend a principle; they obey their instincts. And indeed the use made of slaves and of tame animals is not very different; for both with their bodies minister to the needs of life… It is clear, then, that some men are by nature free, and others slaves, and that for these latter slavery is both expedient and right.

Select excerpts from Aristotle and Black Slavery: A Study in Race Prejudice by Mavis C. Campbell (Race XV, 3 [1974]):

Aristotle, in fact, had a tremendous impact on Black slavery, and he, perhaps second only to the Bible, was one of the chief sources to be quoted in the defence of slavery both by European clerics and philosophers as well as by slave masters and educators of the South…

… Aristotle maintained that some men were by nature slaves. ‘But is there anyone’, he inquired, ‘thus intended by nature to be a slave, and for whom such a condition .is expedient and right? …. There is no difficulty in answering this question on grounds both of reason and of fact. For that some should rule and others be ruled is a thing not only necessary but expedient’.[2] Aristotle, like Plato, saw slavery as more than just an isolated social phenomenon, but rather as intrinsic to the form and purpose of being. Slavery was as natural as other relationships of superior over inferior, such as soul over body, reason over passion, intellect over appetite, husband over wife,3 father over children, men over animals and so on.[4] …

Thus it was that early Spanish Bishops, when baffled by the native Indians of the New World and undecided about the treatment to be meted out to them, did not hesitate, as Lewis Hanke has pointed out,[12] to apply the Aristotelian theory of the natural slave to them. Perhaps the first modern to apply the Aristotelian theory of the natural slave to the Indians, was John Major, a Scottish Professor in Paris, who in 1510 published a book on the subject.[13]…

If these were the prevailing views regarding the Indians during the Spanish expansion into the New World, what then were the views on the ‘Negro’? The most significant point here to note is that Las Casas and Sepulveda conducted their momentous debate on behalf of the Indian in 1550 as if the ‘Negro’ did not exist – although Black slavery was well known in Iberia and was becoming well established on the plantations and in the mines in the New World. Las Casas himself was largely responsible for the growth of Black slavery in the New World when in 1517, he advised Charles V to replace Indian slavery with the ‘hardier’ Blacks from West Africa.[20] Although he is alleged to have regretted this later, this did not prevent him from owning Black slaves.[21] Similarly, other outstanding advocates of the Indians in Mexico were the strongest defenders of ‘Negro’ slavery.[22]…

Now, although Aristotle lost some of his pre-eminence during the latter quarter of the seventeenth century and had a mixed reception throughout most of the eighteenth century as mentioned earlier, he was again the rage in the nineteenth century. In this century, all slave societies in the New World were under attack and there arose the need of slave owners to defend the system with the greatest vigour…

W.S. Jenkins is prepared to argue that ‘the Aristotelian influence upon Southern thought was strong and may be traced through much of the pro-slavery literature. Probably to no other thinker in the history of the world did the slaveholder owe the great debt that he owed Aristotle‘.[37] In a sense, Aristotle earned this notoriety almost – one is tempted to say – unfortunately. For alas for the moderns, he did not leave guidance for the physical detection of the natural slave; he did ponder the question, but finally concluded that there was no physical hallmark by which to spot this inferior being.[38] Be it remembered that Aristotle was well acquainted with Black folk, yet modern pro-slavery protagonists who were influenced by him turned a blind eye on this and found no difficulty in labelling the ‘negro’ inferior and therefore suited only for slavery.

Marx is a complete Aristotelian! This was a surprise? His views don’t make any sense without the Aristotelian background! The whole point of Marx’s analysis of capitalism is that capitalism is unnatural because it thwarts the actualization of our essence as self-conscious and creative beings! That’s not even an esoteric reading — it is literally what he says in the 1844 manuscripts.

Or, more precisely, Marx follows Hegel in thinking that the challenge in modernity is to rethink Aristotle in light of Kant — Marx’s criticisms of Hegel notwithstanding.

What Kant understood perfectly well is that personhood is not a descriptive status, but a normative one. To regard someone as a person is not to classify them, as if we’re doing an inventory of the world’s contents — rather, to regard someone as a person is to commit oneself to acting in specific ways.

This is why Kant’s agnosticism about things in themselves doesn’t affect the substantive core of the categorical imperative.

However, Kant’s agnosticism about things in themselves is relevant for his moral theory in three major respects: it shows that we are rationally entitled to regard ourselves as having libertarian freedom even though to ourselves we always appear causally determined, we are rationally entitled to believe that the order of creation is organized by a benevolent and supremely wise Creator even though we cannot empirically confirm or deny His existence, and that we are rationally entitled to regard ourselves as existing in some form or other despite the death of the body even though dualism cannot be empirically established.

When Kant says that he needed to restrict knowledge to make room for faith, what he means is that he is agreeing with Hume that all knowledge is limited to what can be experienced in the environment (“outer sense”) or one’s own consciousness (“inner sense”). But he is also pointing out that this limitation on knowledge is not a limitation on what we are rationally permitted or obligated to believe.