Pascal’s Wager is widely misunderstood by atheists and theists alike, as Glen Scrivener and Graham Tomlin explain in this video. They’re right about that, but they also claim that the original version of the Wager is more robust, which I think is a mistake. It falls to many of the same criticisms as the popular version and then some. More on this in the comments.

51 thoughts on “Pascal’s Wager revisited”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Roger Zelazny seems appropriate here. The agnostic’s prayer:

Insofar as I may be heard by anything, which may or may not care what I say, I ask, if it matters, that you be forgiven for anything you may have done or failed to do which requires forgiveness. Conversely, if not forgiveness but something else may be required to insure any possible benefit for which you may be eligible after the destruction of your body, I ask that this, whatever it may be, be granted or withheld, as the case may be, in such a manner as to insure your receiving said benefit. I ask this in my capacity as your elected intermediary between yourself and that which may not be yourself, but which may have an interest in the matter of your receiving as much as it is possible for you to receive of this thing, and which may in some way be influenced by this ceremony. Amen.

John Harshman:

That’s beautiful. What deity could fail to be moved by such an earnest appeal?

I usually don’t watch videos, but I’d be interesting in your thoughts, keith, if you felt like writing about them.

The disagreement seems less about what Pascal’s wager is than about its purpose, and I think the video may have incorrectly stated what the various atheist think that is.

John:

Right. Scrivener says:

That’s not what the atheists in the video are saying. They think Pascal is offering a reasoned argument not for God, but rather for belief in God, which is quite different.

aleta:

I’ll have some time to do that later today.

keiths,

Exactly. Further, the purpose of the wager doesn’t answer its problems of logic, and if it has such problems, it can’t serve Pascal’s purpose, as it’s not a rational wager.

Nuances later, but for anyone who isn’t familiar with Pascal’s Wager, here’s the gist:

God either exists, or he doesn’t, and you either believe in him, or you don’t. There are four possible combinations:

1) You believe in him, and he exists. Result: a blissful eternity in heaven.

2) You believe in him, but he doesn’t exist. Result: oblivion after death, but you haven’t really lost anything by believing while alive.

3) You don’t believe in him, and he exists. Result: an agonizing eternity in hell.

4) You don’t believe in him, and he doesn’t exist. Result: oblivion after death.

If he doesn’t exist, oblivion awaits you, so it makes no difference whether or not you believe. If he does exist, it makes a huge difference. You’re much better off if you believe. Therefore, the safe bet is to believe.

Lots of problems with this, but that’s the Wager.

The video starts with clips of various prominent atheists criticizing the Wager. They raise some common objections:

1) The Wager assumes that God is stupid enough to be fooled by insincere declarations of belief. (Pascal doesn’t actually make that assumption. More on that later.)

2) It neglects the possibility that some religion other than Christianity might be true. Christianity and atheism are not the only options.

3) It assumes that God values belief, but why make that assumption?

4) There is a non-negligible cost to living your life according to false religious beliefs.

I would add these objections:

5) Belief isn’t a matter of choice. We can’t force ourselves to believe something simply because we think we’d benefit from believing it. (Pascal is aware of this problem and tries to address it, as I explain in the comment below).

6) The Wager doesn’t take into account our estimate of the probability that Christianity is true.

7) To reason based on assumed infinite rewards is questionable.

More on each of these in later comments, plus additional objections.

Objection #1:

Pascal doesn’t actually make that assumption. He thinks that we must genuinely believe in order to be saved. His argument is for genuine belief, not for mere declarations.

This ties in with Objection #5:

If we can’t simply decide to believe something, and if insincere declarations of faith won’t cut it, then what’s the point of the Wager? How do we arrive at belief? Pascal’s answer is that we have to grease the skids for belief by living a Christian life. Belief will naturally follow:

To me, that sounds like self-brainwashing: If you want to believe in Christianity, immerse yourself in it and behave as if it were true. You’ll start to believe it. It works for Scientology, so why not for Christianity?

Which raises the obvious question: why should I brainwash myself into Christianity versus any of the other belief systems available to me? Why brainwash myself at all?

keiths,

Emersion can lead to brain washing and it may not. You currently believe the bible is a fairytale but you may be wrong. Lee Strobel (a case for Christ) was an atheist and had an objective of disproving the bible. He failed and that defined the rest of his life. Pascals wager had little or nothing to do with his conversion.

Then your comment has little or nothing to do with this topic.

colewd:

No, I think the Bible is a collection of books written over a span of 1,000+ years by a bunch of different people with different viewpoints, different cultural backgrounds, and vastly different ideas about the nature of God. It’s full of errors and contradictions and is definitely a human construction. When you label the Bible as “God’s word”, you are profoundly insulting him.

Not sure what “disproving” the Bible means, but proving that it’s unreliable and self-contradictory isn’t difficult at all.

The topic of this thread is Pascal’s Wager and its many flaws. Whether it convinced Lee Strobel is irrelevant.

Objections #2 and #6 are related:

Objection #2:

Objection #6:

Many religions promise infinite rewards to adherents, and even within those religions there are multiple sects and denominations with differing views on how those infinite rewards can be secured. The Wager is binary — believe or don’t believe — but the situation in reality is not. If there were just a single option that led to an infinite reward, then by Pascal’s logic, that would be the one to choose. But since there are many options, we need some other criteria in order to make our choice. The probability that a religion is true (if we can estimate it at all) is a crucial factor.

Even worse, the choices aren’t limited to established religions. It’s possible that God exists but that none of the religions on offer are true. Maybe the only people who get to heaven are those who venerate turnips, in which case we’re all screwed.

Lastly, this whole notion of reasoning based on infinite rewards is flawed, as I’ll discuss later.

ETA: On a hunch, I googled “Does anyone venerate turnips?” and got this from the search AI:

An Irish turnip-o’-lantern:

keiths,

That response was brought to you by several thousand gallons of finest Texan cooling water…

A further derail: in the UK, turnips are variously either the large things or the small ones, varying by region. Those who call the small ones turnips call the large ones Swedes. But no-one, anywhere, makes a Swede Lantern. Always turnip (for those not infected by that heretical pumpkin nonsense). No-one would show up with a carved tiny ‘turnip’. This is my gotcha for anyone denying the True Turnip. I confidently expect my reward for keeping the faith. Now back to your scheduled programming.

My own rejection of religion (aged 11) was rooted in the realisation that there was a suspicious geographic, or cultural, component to reward. I was born into a culture offering eternal reward for adopting the local belief? Heck, that was lucky, wasn’t it?

This thinking itself is strongy conditioned by Anglo-centric or Western-centric monoculture. If travelling outside of this sphere has not alleviated it, then you have not seen the world enough and not given it enough thought.

I find everything in Pascal’s Pensées suspicious. Upon my reading, it is not at all a philosophical work. It is not even a work. It is made up of scattered reading notes by Pascal. There are many passages that are barely rewordings of something else that Pascal was reading, not what he was thinking for himself or researching towards. The appropriate place of Pensées in Western philosophy is the dustbin.

As far as I can tell, persistence of belief, at least in a religious sense, is something that either takes root in the mind or does not, probably not much later than age 6. Certainly by the age of 8, a person either believes for life, or is condemned to lifelong inability to understand what must go on in the mind of someone like colewd. I sometimes read about individuals who abandoned their belief in their childhood faith in god, and sincerely thank god that they have escaped! And I sometimes read about people bouncing from one faith (or sect within a faith) to another, needing some structural, organized underpinning for their convictions but unable to find anything close enough to believe. The small details of most organized religions can get pretty bizarre.

When Trump claimed he could shoot someone on 5th avenue and not lose a single vote, he was succinctly describing the persistence of religious faith. I’m basically with objection #5 here – once one’s position toward religion “sets up” by age 6, choice in this matter is moot. And before age 6, one wouldn’t particularly expect a person to be able to make such a philosophical choice. Presumably Pascal had reached an age where he could rationalize his faith to his satisfaction. Just as Richard Dawkins (The God Delusion) rationalizes his.

Allan:

Some questions demand answers, drought or no drought.

Oh dear. The sectarian splintering has already begun. Here are thoughts from one adherent. I’m a rutabaga guy myself.

Allan:

I presented this thought experiment to colewd a while back:

Flint:

There are lots of counterexamples, including me. My apostasy happened gradually, starting around age 14. Some people make it well into adulthood before deconverting. Brandon of Mindshift, for example, was in his 30s when he left Christianity. And he was in deep.

Erik:

That’s exactly what it is: a posthumous collection of notes for a book that Pascal had planned to write. No discredit to Pascal for the fact that they’re fragmented and unpolished since he never intended to publish them in that form.

I’m aware of multiple counter examples, yet I retain my doubts. I’ve known plenty of “Sunday Christians” whose nominal beliefs are never really explored. Congress seems infested with “devout god-fearing Christians” whose policies are the exact opposite of Christian teachings. So if your faith is more expedient (or taken for granted and not examined) than sincere, it’s probably not that hard to discard it – except of course if you hold elective office, your career depends on this role-playing.

And at the other end, cult followers remain devout regardless of anything Dear Leader says or does. The leader can flop from one side to the other almost daily, and the followers flop right with him and literally cannot see that they’re doing this.

So religious belief might be a spectrum, maybe tied to self-identity.

Are there many (or any) prominent elected US politicians who are openly atheist? The deep embedding of religion in US society is peculiar to me as a Brit, where it is a complete non-issue in most regards.

Flint:

That’s why I mentioned Brandon. Missionary parents, Christian schools, attended church 5 or 6 times a week, majored in Bible studies at a Christian college. Of his mom, he says

He describes his background here in a video about his deconversion.

He sums it up thus:

He was in deep. Definitely not a “Sunday Christian”.

I wasn’t as rabid a believer as Brandon, but I took my faith very seriously and even considered (at my pastor’s urging) whether God was calling me to the ministry. So yes, sincere and serious believers can deconvert well after age 6.

Allan:

There have been a few, but not many. I know Barney Frank was an atheist, and so was Pete Stark, who represented a district next to mine in California. Not sure if there’s anyone currently serving in Congress who is openly atheist.

Yeah, it’s a huge deal here. Atheists are among the least trusted groups in the eyes of the American voters. There’s been some interesting polling on that which I’ll dig up later.

Here’s the polling data (from Gallup):

Willingness to Vote for a “Well-Qualified” Presidential Candidate (% Yes)

Candidate Trait 1958 1983 2007 2015 2020

—————————————————————————————–

Black 38 88 94 92 98

Catholic 71 90 95 93 96

Jewish 63 89 94 91 93

Woman 55 87 88 92 93

Atheist 18 45 45 58 60

Muslim — — 45 60 66

Gay/Lesbian — 24 55 74 78

Under 40 — — — 71 87

Socialist — — 47 47 45

Transgender — — — — 66

At least we’re ahead of the socialists. Lucky they don’t ask about fascists, though.

Here’s the 2020 data by party ID.

John:

That would be interesting. A lot of Trump supporters are fascists but would deny it because they know ‘fascism’ is Something Bad, whether or not they know what the word means.

Of the 83% of Republicans who say they wouldn’t vote for a socialist, I wonder how many could actually define the word ‘socialism’ if asked.

keiths,

I presume this refers to Presidential elections, since so few are willing to vote for a candidate under 40.

The level of bigotry is disheartening. 5% of Democrats refuse to vote for a Jew? 11% refuse to vote for gays or lesbians? (Tough luck for Pete Buttigieg, my #1 candidate.) “Evangelical Christian” is at least a choice.

John,

Yes, all of the numbers above concern hypothetical presidential candidates, and yes, I think Buttigieg would make an excellent president.

There are bigots in both parties, sadly, but at least the Democratic leadership doesn’t pander to them the way the Republicans do. Trump is running around saying “Barack Hussein Obama” every chance he gets.

The attachment of a lame pejorative to a name is a distinctively right-wing thing to do; Trump’s rhetoric is full of it (“Hussein”. should not be a pejorative, of course). The “Comrade Kamala” thing bugged me. Many Americans seem very hazy about what is and isn’t Communism, and unquestioningly latch on to simpleton slogans like that. Rooted in historic Russophobia, which is quite ironic.

keiths,

Hiking the PCT, I was made very welcome by religious groups. But the intensity of it was a culture shock. I eavesdropped a conversation between a couple of guys over their religious doubts. One’s father was a pastor, but he himself was struggling with the Adam and Eve story, and it was causing a rift. In my own family, my daughter converted at university, having been ‘raised atheist’ (in an entirely passive mamner). It simply never comes up as a topic, and causes no issues.

Allan:

Yeah, the US is an outlier among western democracies when it comes to religiosity. I’m told that in Oklahoma, the first question you’re asked upon meeting someone new is often “What church do you go to?”

Growing up in Indiana, my elementary school offered a Bible class in the middle of the afternoon. It was blatantly unconstitutional, but the fig leaf was that it was voluntary and that it wasn’t held on school property. We walked a quarter of a mile to the nearest church, then walked back to school when class was over. (I still have the Bible I won for memorizing the most Bible verses.) It all seemed perfectly normal at the time, but in retrospect, I’m appalled.

Allan,

Totally tangential, but your Adam and Eve reference reminded me of the origin story of “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida”, which I learned for the first time this morning:

Objection #3 from my list above:

He might value belief, or he might not care. He might actually disdain belief and prefer to stay hidden. He might get annoyed and send you to hell if you bother him too much by praying all the time. He might punish you for believing in him on insufficient evidence. He might love turnips (God’s plant messengers on earth) and lock you out of heaven if you don’t. A proper wager would have to account for far more possibilities than just “God saves the people who believe in him.”

The Wager also assumes that if God exists, heaven exists, but that’s just an assumption. It’s possible that God exists and heaven doesn’t. It’s possible that there is no afterlife at all. It’s possible that we get reincarnated. It’s possible that the afterlife is quite different from either heaven or hell — it might be something like Sheol or the Greek underworld. And so on.

I picture my arrival at the Sorting Office.

“You didn’t believe. Down you go”.

“Well, I believe now. You’re sat right there”

“Tough noogies. There was overwhelming evidence you chose to be blind to”.

“The evidence was unconvincing”

“Tough noogies”

…

“Of all the moronic, harebrained…”

I have my own wager.

It is that we’ll never know.

It’s the same wager I make about the existence of alien civilizations. Except that if they exist, there’s a nonzero chance that humans will eventually know.

Objection #7:

Pascal’s Wager is a misapplication of the notion of “expected value”. For anyone unfamiliar with the concept, the expected value of a choice or a bet is the average return you get by making that choice or that bet.

For example, suppose a casino offers a (rather boring) game. You roll a pair of dice. If you roll a 7, you win $6. If you roll a 12, you win $108. Otherwise you get nothing. You play the game again and again. On average, what do you win per play?

Here’s how you figure it out. How many ways are there to roll a 7? Well, if the first die is a 1 and the second is a 6, you’ve rolled a 7. Let’s designate that as (1,6). Using that notation, here are all the ways you can roll a 7: (1,6), (6,1), (2,5), (5,2), (3,4), and (4,3). 6 different ways to get a 7.

What about rolling a 12? There’s only one way: (6,6).

How many distinct rolls are possible? The first die has 6 possible values, and the second die has 6 possible values, so the number of possible (m,n) combinations is 6 times 6, or 36.

6 of those combinations yield a 7, so the probability of rolling a 7 is 6/36, or 1/6.

1 of those combinations yields a 12, so the probability of rolling a 12 is 1/36.

There are 29 other combinations, so the probability of getting one of them is 29/36.

We can now compute the average payout by multiplying the probability of each payout by the value of each payout, and adding them:

Plugging in the appropriate values, we get

…which comes out to an average payout of $4 per play. In other words, the expected value of playing is $4 per play, and if you play 10,000 times, your expected winnings will be around $40,000.

Let’s say the people running the casino charge you $3 to play. On most rolls, that works out well for them, because 29 times out of 36 you’ll roll something other than 7 or 12. In those cases, you pay them $3 and they pay you nothing. They get to pocket the $3. If you roll a 7 or 12, however, you get more money back than you paid the casino.

Sometimes you win, but more often you lose. However, when you win, you sometimes win big, getting $108 back for an investment of $3. If your goal is to make money and you plan to be in the casino all weekend, is it worth playing this game? It isn’t immediately obvious unless you’ve computed the expected value, but once you do the calculation above, you know that the expected return is $4 for every roll of the dice, so it becomes clear. You win a dollar on average for every play, investing $3 and getting $4 back. The money will accumulate. The people running the casino are idiots for charging only $3 to play this game.

Now let’s say you have a choice between playing that game and another game which I will now describe. In this second game, you roll ten dice at a time, and if the sum is 60 — (6,6,6,6,6,6,6,6,6,6) — you win $350 million. Otherwise you get nothing. The casino charges $3 for this game, just like the first game. Should you play this game instead of the first?

You might naively think, “Well, let’s compute the expected value for this game, just like we did for the first, and if it’s better than $4 — the average payout for the first game — then this is the more profitable game to play.”

So you set about calculating the expected value. There are possible combinations, and exactly one of them — (6,6,6,6,6,6,6,6,6,6) — yields a 60. That means there are

possible combinations, and exactly one of them — (6,6,6,6,6,6,6,6,6,6) — yields a 60. That means there are  combinations that don’t yield a 60.

combinations that don’t yield a 60.

The probability of a 60 is therefore , and the probability of anything else is

, and the probability of anything else is  . The expected value of the payout is therefore

. The expected value of the payout is therefore

which comes out to over $5.75 per play. Much higher than the first game, and it means that on average, you’ll net over $2.75 per play vs the $1 per play that you’d get with the first game. So you should play the second game, right?

Well, no. The reason the average payout is higher is because the payout for rolling a 60 is enormous — $350 million. However, the probability of a 60 is only 1 in about 60.5 million. Even if you spend all weekend in the casino, you’re almost certainly not going to be able to play enough rounds to come out ahead. Expected value tells you the long-run average payout, but only in the long run. In the short run, especially when success is extremely unlikely, the actual outcome can diverge wildly from the predicted average.

Let’s be generous and say that you can roll once per second, and that you’re going to do this for 48 hours straight. That’s

I’ll spare you the math, but the likelihood of rolling a 60 in 172,800 tries is minuscule — less than 0.3%. Rather than making money, you’re overwhelmingly likely to walk out with a huge loss, because each play costs you $3, for a total of $3 x 172,800 = $518,400. Half a million bucks lost, and nothing gained, unless you’re extremely lucky.

What went wrong? Well, the expected value calculation is correct, so that isn’t the problem. The problem is that the expected value isn’t a useful criterion unless you’re going to play enough rounds for the true odds to really kick in, and that isn’t physically possible in 48 hours. Furthermore, even with no time limit, it would still take you around 42 million plays to have a better than 50% chance of rolling a 60. At one roll per second, that’s about a year and four months, assuming you play 24 hours per day with no rest breaks. And at $3 a pop, it will cost you over $120 million.

So if you have millions of dollars, a year and a half of free time, and an extreme tolerance for boredom, you might walk away ahead of the game. If all you have is a mere weekend, though, you’re screwed.

The moral of the story is that you can’t blindly use expected values as a criterion for deciding which games to play or which bets to make. More on how this applies to Pascal’s Wager in a future comment.

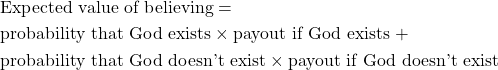

Time to look at expected values in the context of Pascal’s Wager.

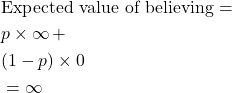

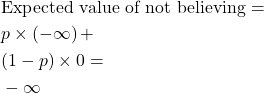

Let’s neglect for the moment the problems mentioned earlier and go with Pascal’s assumptions, which stipulate a binary choice — believe or don’t believe — and a Christian God who, if he exists, will reward believers with a blissful eternity in heaven — an infinite payout — and punish disbelievers with an agonizing eternity in hell — a payout of negative infinity. If he doesn’t exist, there’s no payout either way.

(1)

We don’t actually need to specify the probabilities (which is part of the problem, as I’ll explain below). We just need to stipulate that they are nonzero and add up to 1. Let be the probability that God exists. Then

be the probability that God exists. Then  is the probability that he doesn’t exist, and

is the probability that he doesn’t exist, and

(2)

(3)

Seems like a slam dunk, right? Infinite reward is a lot better than infinite agony. But notice that those expected values don’t change regardless of the value of p. That should raise your eyebrows.

What if p is minuscule? Let’s say that p is equal to the following probability: You have a sphere the size of the earth, and you fill it with grains of sand. ChatGPT estimates that there would be 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 grains of sand in the sphere. You designate a single grain as The Special Grain, and the question is: what is the probability that a grain you select at random is The Special Grain? It’s 1 divided by 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 — an almost unfathomably small number, but not zero.

We’re stipulating hypothetically that the probability of God’s existence is equal to that tiny Special Grain probability. So what’s the expected value of believing? It’s still , because multiplying even that tiny probability by

, because multiplying even that tiny probability by  yields

yields  . Likewise, the expected value of of not believing is still

. Likewise, the expected value of of not believing is still  .

.

Change that minuscule to a very high value — say 0.999999 — and the expected values remain the same: \inf for believing and -\inf for not believing. Two wildly different situations, but the same expected value. There’s something fishy going on here.

to a very high value — say 0.999999 — and the expected values remain the same: \inf for believing and -\inf for not believing. Two wildly different situations, but the same expected value. There’s something fishy going on here.

Now, you might argue that it’s still rational to believe, even if is minuscule, because having even a sliver of a possibility of hitting the jackpot is better than having no sliver at all. Likewise, even if there’s just a sliver of a possibility of eternal torment, it’s better not to take our chances.

is minuscule, because having even a sliver of a possibility of hitting the jackpot is better than having no sliver at all. Likewise, even if there’s just a sliver of a possibility of eternal torment, it’s better not to take our chances.

And that’s actually true, given the analysis so far. (Like us, Pascal himself didn’t assign probabilities.) However, there’s one thing we haven’t yet taken into account: the cost. The cost of believing is that you have to live your life as a Christian. That means going to mass (Pascal was Catholic), tithing or other giving, constraining your behavior to satisfy Church dictates, etc. It also means brainwashing yourself into believing, since only genuine belief can win you the desired eternal reward. None of these costs are incurred if you remain a nonbeliever.

Pascal addresses the cost issue by arguing that living as a Christian is a net gain even if God doesn’t exist, since the benefits of a Christian life outweigh the additional costs. I don’t buy it, but I’ll save that argument for later.

How does expected value change when we take cost into account? It doesn’t. The cost is finite, so it is swamped by the positive infinity of eternal bliss and the negative infinity of eternal torment. Since the expected values haven’t changed, we’re still better off believing than not believing, right? Not necessarily. The expected values have misled us, just as they did in the dice game mentioned in the previous comment.

If is minuscule, as in the Special Grain scenario, then belief might not be worth it even if the expected value is infinite. If you choose not to believe, then the cost savings are a sure thing, although they’re finite. You might decide that it’s better to grab the sure thing and take your chances on missing out on the jackpot or getting unlucky and ending up in hell.

is minuscule, as in the Special Grain scenario, then belief might not be worth it even if the expected value is infinite. If you choose not to believe, then the cost savings are a sure thing, although they’re finite. You might decide that it’s better to grab the sure thing and take your chances on missing out on the jackpot or getting unlucky and ending up in hell.

An analogy: Someone invites you to invest in their startup. The pitch isn’t very promising and the odds of success are low, but the payout will be enormous if the venture actually succeeds. Let’s say the payout is large enough that the expected value is super high, as it was in the case of the dice game. Do you invest? Well, there’s a cost to investing, and you might prefer to hang onto the money rather than gambling on an unlikely payout. On the other hand, you might be willing to take your chances since the payout will be huge if you get lucky. The point is that the expected value alone isn’t enough to justify your decision either way. You need to know the probability of success.

The analogy is imperfect, but it makes the point: an infinite expected value isn’t always as impressive as it might seem at first glance. You need criteria other than expected value, including an estimate of the probabilities.

As for the investment, so for Pascal’s Wager. Objection #6 applies:

keiths,

This also collides with the objection that Christianity isn’t the only religion. If Allah exists, there’s infinite benefit to Islam, so the expected value analysis fails even if we believe it. Belief in Christianity and Islam are mutually exclusive plus or minus infinite benefits, depending on which is true. Now add in all the other religions that make various promises and/or threats.

John:

Right, and that’s another reason why you’d have to be able to estimate the probabilities of the alternatives in order to employ the Wager correctly. Pascal clearly believes that you can’t, and says

…which undermines the Wager.

Yet he employs reason in defending Christianity elsewhere in the Pensées, which would seem to undercut his claim above unless he is saying that while God’s existence isn’t defensible via reason, Christianity is defensible once you’ve decided that God exists. I’ll comment later once I’ve read the relevant parts of the Pensées.

Pascal, immediately before the passage I quoted above:

He’s telling us that sensible Christians don’t offer proofs. So what does he do? He offers proofs, later in the Pensées:

And:

In an nutshell: We can’t possibly prove that Christianity is true, and here are the proofs that Christianity is true. If he had lived to write the book, perhaps he would have finessed the contradiction.

* A footnote says this is a reference to 1 Corinthians 1:18:

Which is weird, because that puts Pascal on the side of “those who are perishing”, who regard Christianity as “a foolishness”. However, that footnote isn’t from Pascal; it’s from a later editor, who presumably was trying to find scriptural support for Pascal’s awkward position.

Anyway, Romans 1:19-20 certainly doesn’t jibe with Pascal:

Pascal isn’t coming across well here. But at least we still have his triangle.

John:

Haha. He was a master of compartmentalization. Brilliant at math and science. Not so much when it came to religion. Scrivener says:

It’s pretty clear that Pascal was projecting, and that the heart is what motivated his fervent belief, but he doesn’t speak for everybody.

As evidence of how heart-driven he was, this was found sewn into his coat liner after his death. He wanted to keep it close to his heart:

Pascal:

In short, the only reason you don’t believe is because of your passions, and that is “a malady” of which you can be cured by brainwashing yourself. No thanks, Blaise.

Tomlin comments:

Even if the Wager made sense (and it doesn’t, for all the reasons already discussed), it wouldn’t compel belief. It would at most compel you to try to brainwash yourself into believing, which might or might not be possible.

Tomlin, echoing Pascal, is claiming that if you don’t already believe, it’s because you don’t want to. In reality, it’s quite common for people to want to believe but to be unable to. That was exactly my situation when I started to doubt my Christian faith as an adolescent. I was happy as a Christian. I wanted Christianity to be true. I prayed for guidance and for God to strengthen my faith. I read the Bible* and concocted apologetic arguments to convince myself. None of it worked, because I wanted to know the truth, and Christianity just didn’t ring true once I started examining it carefully. (Ironically, my deconversion was inadvertently assisted by a Mormon friend who as far as I know is still a believer.) Reason won out over my heart. Pascal, Scrivener, and Tomlin all claim to believe whatever their hearts tell them to, rationalizing it afterwards, but they don’t speak for all of humanity. Some of us aren’t like that.

Scrivener:

That’s true, but it’s trivially true. The people who go to church go because they want to (assuming they’re not being forced to). The people who go to synagogue go because they want to. The people who stay home or play golf do it because they want to. The people who pay hundreds or thousands of dollars for idiotic Scientology “auditing” sessions do so because they want to.

What Scrivener is really trying to say is that people who don’t attend church are doing so out of stubbornness or laziness, not because they have good reasons not to attend. Well, is Scrivener being stubborn by not going for Scientology auditing or doing puja at the local Hindu temple? Should he start doing so in order to brainwash himself into becoming a Scientologist or a Hindu?

The reason I don’t do any of those things isn’t because I’m lazy or stubborn, it’s because I don’t think Christianity, Scientology and Hinduism are true. Whether I wish they were true is irrelevant. I’ll bet Scrivener agrees with me about the last two, so it should be easy for him to understand why I take the same attitude toward the first. Head over heart.

* Advice for anyone who wants to retain their Christian faith: do not read the Bible. Or if you do, be very selective about the parts you read. The Bible, when read carefully and non-selectively, is a catalyst for apostasy.

Scrivener:

Tomlin:

Scrivener:

If my heart chooses not to believe, and reason is just a tool for rationalizing that choice, as Scrivener claims, then the Wager is neutered. The Wager is based on reason, but if reason’s role is simply to validate what I’ve already chosen, and not to override that choice, then the Wager has no force. It can’t change what I want.

In other words, if I don’t want to believe and attend church, why would reason persuade me to take steps that would cause me to believe and attend church, if reason’s only role is to validate my desire and not change it?

I think the problem is that Scrivener is oversimplifying Pascal’s position when he says “What the heart loves, the will chooses, and the mind then justifies.” Reason doesn’t merely justify what we want; it can change what we want, and that’s exactly what Pascal is trying to do. He wants to flip us from “I don’t want to believe” to “I do want to believe”, in which case we’ll be willing to follow his advice and brainwash ourselves.

I suspect that what Pascal is really trying to say is this:

Reason can’t tell us whether God exists or not, and it can’t tell us which is more likely, so whether we believe or not is based not on reason but on what our hearts desire. Nonbelievers don’t want to believe in God, so they don’t believe.

It isn’t that they use reason to rationalize that choice — they can’t, because Pascal thinks that reason can’t justify one choice over the other. Reason doesn’t apply here. But that doesn’t mean that reason’s job elsewhere is simply post-hoc rationalization. Reason changes what we want all the time; for instance, a Canadian might want to vacation in Florida, but after seeing Trump slap tariffs on Canada and harangue them about becoming the 51st state, they no longer want to.

In short:

Pascal thinks that reason doesn’t apply when deciding whether God exists, so the heart prevails and we believe or not based on our desires. In other areas, reason still applies, and the Wager can reason us into changing what we want. “I don’t want to believe” changes to “I do want to believe, because that’s the better and safer bet.”

What the heart loves sounds like the research showing that decisions are made before we become consciously aware of them.