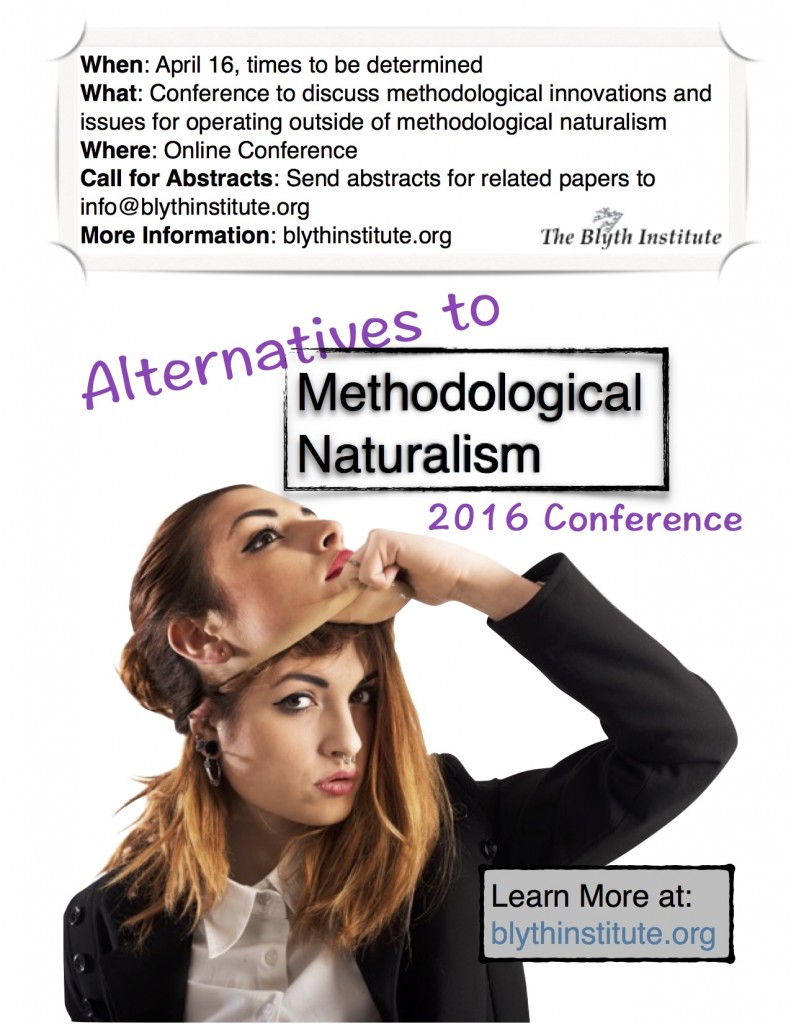

I thought some of you might be interested in an online conference April 16, Alternatives to Methodological Naturalism. The goal of the conference is to have a discussion among interested researchers about what other modes of investigation one might employ that were counter to methodological naturalism.

This is a cross-discipline conference, and we are hoping to get submissions in physical science, biology, economics, computer science, psychology, and other areas of inquiry.

Anyway, whether you are interested in presenting or attending, please fill out our contact form and we will mail you when more details become available.

The organizers of the conference are myself and Eric Holloway. This is somewhat of a continuation from a previous conference organized by myself and Dominic Halsmer, The Engineering and Metaphysics 2012 Conference, the proceedings of which are here.

I doubt that methodological naturalism rules science in any meaningful sense, or that it can actually be defined non-circularly. I can’t remember it ever coming up in a science class, and I see little reason for its existence other than to avoid stepping on the toes of the religious.

Meanwhile, “supernatural” claims are investigated so long as they have observational entailments.

I doubt that there’s any decent alternative to empiricism for deciding anything that is potentially observed by our senses, indeed, but that has no reliance on as meaningless a word as “natural” happens to be.

Glen Davidson

I’ll plan to follow online.

Frankly, I have never been able to make sense of the arguments for or against methodological naturalism. It seems to all be about the alleged importance of a completely unnecessary assumption.

William J Murray has thoughts on alternatives, I believe. Unless he’s changed his mind, again.

So I went digging around the website. Are you the sole contributor, Johnny B?

http://www.blythinstitute.org/site/sections/11

Yeah, I don’t know what the term “naturalism” brings to the table that isn’t full of unnecessary metaphysical baggage. Methodological Pragmatism is, IMO, a much better conceptual framework. But then, I already posted a thread here on it.

And at UD too, I believe. How was it received? Care to spell out the key differences?

I’ve already made my case here in that prior thread.

This was the thread here where I came up with “Methodological Pragmatism”.

My first post there:

I think that pretty much still holds up pretty good.

I encourage everyone interested to re-read that whole thread paying particular attention to WJM’s examples.

Richardthughes –

“Are you the sole contributor, Johnny B?”

It depends on what you mean. There are a number of contributors to our previous conference, Engineering and Metaphysics, but not to the organization itself. To the website, I have been so far the only contributor. To the organization, so far, I am the only public one. There are a few others who may start doing more publicly with the Blyth Institute. I would love to have more, but there is little I have to offer anyone to join up. I’m looking, though!

GlenDavidson –

I agree with the second part of that sentence, but not necessarily with the first. Basically, there are a set of prejudices for that substitute for the definition, and those prejudices do impose themselves on science, and the ones who enforce this explicitly do so because they believe that their prejudices are well-defined definitions rather than simple prejudices.

Neil –

Well, I think that the second sentence is as good of an argument against methodological naturalism as any. The question is, what sort of new things might we do that we weren’t thinking of beforehand because we were holding on to unnecessary assumptions?

Additionally, I think that methodological naturalism *has* done some important work. It is like having a fence around animals. The fence might be in an arbitrary location, but it keeps all of the animals where you can see them and take care of them. The problem is, if the number of animals grows, then you have to reconstruct your fence. Then you ask yourself what your new fence should look like, or if you need to do something altogether different. That’s the goal of the conference.

Thanks RH! That is a good thread. Do you remember what thread came before that one in the discussion?

Here’s a keeper:

In that thread, a poster named “heleen” tried to claim that naturalism and pragmatism were functionally the same thing.

From wiki:

Why is cosmological metaphysics being used to constrain/control the method of science, when Pragmatism is unoconcerned with such metaphysics?

William J. Murray,

Well I hope you’ll be contributing to the conference. Goodness knows how much further along we’d be if this was used in history.

I would dispute the characterization of pragmatism as unconcerned with metaphysics. Some pragmatists are unconcerned with metaphysics and a few are openly scornful of it (Richard Rorty, Hilary Putnam). Other pragmatists are concerned with metaphysics. Some pragmatists are also naturalists (Dewey, Sellars, Margolis) and some pragmatists are not (James, Rescher). Pragmatism, as an epistemological approach, contrasts with dogmatism and with skepticism, and in particular contrasts with the two main varieties of dogmatism, rationalism and empiricism. It also contrasts with “scientism,” though that notion is much harder to characterize. A lot of my work focuses on developing the contrast between pragmatic naturalism and scientism.

That said, I agree with most of the commenters here that “methodological naturalism” is not a useful notion. I don’t see what the difference is supposed to be between “methodological naturalism” and just emphasizing that good explanations of causal structures should be grounded in empirically confirmed models. I agree with Feyerabend that there’s no one right method for generating and testing those explanations.

My simpleminded understanding is that “methodological naturalism” means these models must be amenable to empirical confirmation. In other words, the methods of science do not permit “supernatural” components in the process of testing or explanation. Intersubjective validation presumes some ground rules as to what “valid” means in the context of science.

Examples. Or we get turbo encabulatored.

Flint,

Eh . . . I don’t know. I mean, there is a real problem with defining “natural” and “supernatural” here, since each gets defined in terms of the other. If “naturalism” just means “anti-supernaturalism” and “supernaturalism” just means “not naturalism,” then it’s hard to see how either concept is being explicated.

I think it’s better to say that good explanations of objectively real causal structures should be empirically confirmed, and empirical confirmation requires some kind of intersubjectively verified reference to spatio-temporal events and description of the properties instantiated at those events. This is more cumbersome than talking about “naturalism”, but it does not invite confusion, and it sidesteps all the interminable debates about “materialism,” physicalism, reductionism, determinism, and so on. And it allows us to understand why economics, history, sociology, psychology, ecology etc. all count as perfectly good sciences without worrying about whether we can understand any of those sciences in terms of fundamental physics (or even if we really need a single theory of fundamental physics at all).

Here, my understanding is that we’re not really talking about the scientific method. Instead, we’re talking about the degree to which the sorts of gods religious people believe in, are regarded as contributing to our understandings of the world. My take is that these other isms you invoke are largely artificial side-effects of the determination to insert religion into science. So I regard “methodological naturalism” or “metaphysical naturalism” or “materialism”, etc., as deliberately political terms, whose purpose is a context shift to redefine the playing field. But probably I’m missing the point.

Kantian Naturalist –

These are all great points. If you were interested, and fleshed them out a little more, I think it would make a great contribution!

Seems that Methodological Naturalism was the focus of Alvin Platinga, whose views are at the core of the philosophical basis of ID. He has framed the ID vs. Evolution debate in terms of ID vs. Methodological Naturalism. I could be way off base, I’m not a philosopher, and I don’t delve into philosophy.

I probably would be classed as a pragmatist scornful of metaphysics. If I can articulate why. When I have a nightmare, even though what I’m experiencing is illusory, I still flee from these illusory threats without giving it much thought.

I don’t give too much thought as to what constitutes real or illusion, I give my best guess. I would probably say, my epistemology is that of a skilled gambler weighing odds and payoffs as best as I can estimate.

Uncertainty rules the day in such venues, and I realized, that most of the decisions and actions of every day life are made with far less facts than what we’d like. The problem isn’t having better metaphysical methodology, it is the lack of empirical facts and our finite capacity to process facts even if all the possible facts of the universe were hypothetically available to us. So even if hypothetically we had access to all possible facts, we’d probably ignore them because we don’t have the ability to process them, so we go to flawed modes of reasoning as a matter of pragmatism.

I encountered a real world example of this. Some mathematical methods of estimating odds in Blackjack can only be done by a high speed computer. Some skilled gamblers, before Nevada passed anti-device laws, would use the computers in their shoes which were operated by the toes of the gambler, and every card that was dealt out was input into this hidden computer, and the computer would vibrate on their feet to tell signal what the Gambler should do (raise bets, take more cards, stand on a hand, etc.) The machine helped some gamblers to obliterate the casinos until the casinos wised up.

Now a days we can only use our brains, and we have to use inexact methods which are only 75% of the theoretical efficiency of a computer. We know our decisions are sub optimal as a matter of principle, but we go with it anyway since that’s the only way to bring home the bacon.

So even if we hypothetically had the right metaphysics, we have some practical limitations anyway…

PS

I used the Advance Omega II counting system which entailed memorize 9 pages of mathematical tables. I miss playing….

Sal –

Even for pragmatists, metaphysics can have an effect, as it shifts your expectations of what is real and what is possible. For instance, bitcoin rests solidly on metaphysical presuppositions. They may be good or bad presuppositions, but they are definitely metaphysical, even if people don’t think of them that way.

So, the goal is to move people’s mental conceptions of what they are and aren’t doing and what they can and can’t do. Whether they internalize it as true metaphysics or not is somewhat beside the point, getting people to rethink the way they are doing things from a new perspective (and gain perspectives from other fields) is valuable for everyone.

By the way, I am hoping to recruit someone from Austrian economics to discuss their concept of methodological dualism.

johnnyb,

Apologies if I sounded dismissive of the conference, I most certainly am not and I’m not dismissive of the conference’s goals.

I actually signed up for the conference and as I mentioned in my signup, if I were accepted to make a presentation, I would offer the following out-of-the-box alternative to MN, not based on any body of philosophical literature but on methodological pragmatism found in decision making where uncertainty and lack of desirable facts is the norm.

I was suggesting “Gambler’s Epistemology and the NIH’s 500 million dollar bet against an MN-based theory.” It is becoming evident that certain philosophical and methodological naturalists like Dan Graur and Larry Moran are infuriated at the NIH 500 million dollar investment in ENCODE, Roadmap, E4, GWAS etc. because the NIH initiatives are providing evidence friendly to the claims of Intelligent Design and even Young Life Creation theories and evidence against some interpretations of evolutionary theory. As Graur said, “If ENCODE is right evolution is wrong.”

A Gambler’s epistemology is to recognize the dearth of desirable facts in situations where decisions are still necessary in the absence of facts. MN inspired physical theories may rule out some real world decision that could be beneficial to society and the NIH vs. evolutionist 500 million dollar gamble is an example.

Rather than MN, a gambler’s epistemology could be operationally superior in exploration of medical and environmental issues, and possibly some issues in the physical sciences and the consequent engineering applications.

Yet he did not say therefore ID, so what’s your point?

Thank you,but in truth I have my hands quite full with my classes and my own research and writing. An occasional comment at TSZ is all I have time for.

I think that this is not quite right, but not entirely wrong.

Plantinga is a Christian philosopher (in fact, I believe he founded or co-founded the Society of Christian Philosophers), and more specifically, an orthodox Protestant analytic epistemologist. He is sympathetic to ID, but from what I can tell, he does not actually care about the debate between ID and theistic evolution.

Plantinga does care about rejecting metaphysical naturalism, which he defines as the position that there is no person as God or any person like God. His major argument against metaphysical naturalism is his EAAN, or Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism, to the effect that if naturalism were true, we would be unable to know if our own cognitive capacities were reliable, and hence we unable to know if naturalism were true. (I’m being very compressed in my presentation of the argument, since the EAAN has been extensively examined at TSZ before.)

On this basis, Plantinga concludes that metaphysical naturalism and science are incompatible. He has a separate argument for why theism and science are compatible.

Now, it is true and interesting that so many people in the ID movement align themselves with Plantinga’s EAAN, and are scarcely troubled by the mere existence of the many, many criticisms of that argument. But it is an epistemological argument that draws on a lot of unstated assumptions about philosophy of mind and philosophy of language; it is not a scientific explanation in any sense. And it is designed to show that metaphysical naturalism is irrational, not that methodological naturalism should be rejected.

For all I know, Plantinga would be happy to say that methodological naturalism is necessary and sufficient for empirical science. (I don’t know if he would say that, but it would be fully consistent with his theism if he were to say that.) And to repeat, I don’t think it matters to Plantinga whether ID or theistic evolution is true — only that it is irrational to believe in atheistic or naturalistic evolution.

KN, I think “atheists” don’t give much of a hoot about ground plane of being arguments. I know I don’t.

The problem I see with theism is in the leap from ground plane to Jesus, metaphorically speaking. Or, to borrow from Gregory, the leap from god to God. From mysticism to Moses.

Requiring a sentient god for truth is just pushing the problem back a level. Not unlike pushing OOL back by attributing it to aliens.

Now you have an OOG problem.

petrushka,

Being a philosopher with some background in science, rather than a practicing scientist, I have more patience with conceptual explications and formal reasoning.

I have no problem with “the ground of being” talk, actually. Some of it resonates with me emotionally, and some of it doesn’t.

The argument that there must be a necessary being — that not all beings can be contingent — is actually a good argument. By that I mean the argument is logically valid and sound. But it does not establish that the necessary being must have any of the characteristics of God. There’s nothing in that argument which rules out the logical possibility that the universe or the mulitverse is the necessary being.

Be that as it may, Plantinga attempts to show that naturalism is internally incoherent. For that reason, the response to Plantinga can’t be that theism is also incoherent — that’s a mere tu quoque.

Consider it this way Suppose Plantinga is right about naturalism. Suppose further that there are no good arguments for theism. On this basis we should conclude that we do not have and cannot have any good reasons for believing that our cognitive capacities are generally reliable. Hence we don’t actually know anything and can’t actually know anything. That’s a victory for the Pyrrhonian skeptic, but not for anyone who wants to say that we can actually know anything at all.

The response to Plantinga can’t therefore be showing that there aren’t any good arguments for theism, but rather showing that naturalism is not self-undermining.

In fact Plantinga himself admits that there are no good arguments for theism. In God and Other Minds he argues that all of the classical theistic arguments are logically invalid, but that our belief in God is a “properly basic belief”. On his view, my belief in other minds is not something that I can logically demonstrate to the satisfaction of the skeptic, but still a belief that it would be irrational to deny. But since God is a mind — albeit an infinite one — the belief in God is also properly basic. (I think this argument is so bad it borders on sophistry, but that’s neither here nor there.)

Here’s the point: vindicating the naturalist’s position that he or she knows anything at all requires rejecting the EAAN. That means showing that we have good reasons to believe that unguided evolutionary processes tend to produce generally reliable cognitive capacities in organisms that have any cognitive capacities at all. But I also think that this burden can be met very easily, using cognitive science and evolutionary theory. The challenge can be met very easily, as indeed has been shown by several philosophers. The burden is really on Plantinga and his supporters to show that the criticisms of the EAAN miss the mark. I for one do not think that they do.

Kantian Naturalist,

Thank you so much for the detailed reply. That was very informative!

Sal

My response to Plantinga: Consider two proto-cavemen, Ogg and Grog, whose cognitive processes are entirely naturalistic. Ogg’s cognitive processes (such as they are) tell Ogg that rocks and dirt are good food; Grog’s cognitive processes (such as they are) tell Grog that fruits are good food.

Which of the pair, Ogg or Grog, is more likely to produce descendants?

Also: Plantinga argues that if our cognitive processes are naturalistic, then they can’t be fully reliable. Well, our cognitive processes aren’t fully reliable—we know of a number of cognitive ‘glitches’, confirmation bias and so on. Why Plantinga then goes on to conclude …therefore, naturalism is invalid rather than …therefore, our cognitive processes are naturalistic is unclear.

Plantinga’s thought processes, for example.

Glen Davidson

This is way off-topic, but I agree with Plantinga, and on a basis similar to the Ogg and Grogg example above. Think about single-celled organisms. Do they think any thoughts? Now, if you suppose that they do, then this argument does not work. However, let’s say that you suppose that they don’t think any thoughts. Therefore, they are perfectly able to function correctly despite a total lack of true thoughts. In fact, they are more adaptive than any land animal. Therefore, the ability to behave functionally is not dependent on having true thoughts, since single-celled organisms don’t have any. Therefore, we cannot say that we are more likely to behave correctly with true thoughts since single-celled organisms do so without any true thoughts.

They don’t have false thoughts either.

The possibility of false thoughts seems to be what bothers Plantinga, although it didn’t bother Kant.

Glen Davidson

That is a fine response to the argument having true thoughts is the one and only way by which it is possible for organisms to behave functionally. Since I did not make that argument, it is unclear why you posted it as an apparent response to something I wrote. Would you care to try again, perhaps asking for clarification if you’re not clear about some part of what I wrote?

But what does “true” mean here.

As I see it, Plantinga is smuggling in theistic presuppositions with his concept of “true”. That is to say, he is assuming something like a central truth giver. I don’t think his argument works with a pragmatic conception of “true”.

Sorry, this is stupid. By this same reasoning organism with legs don’t need to have legs which “behave correctly” because single cell organisms thrive without any legs at all. But where legs have indeed evolved – for some advantage of escaping the drying mud puddles or reaching far away food sources, or whatever – the skeleton-muscle configurations which are more reliable in the population’s environment will be selected over those that are less reliable. It is a matter of life or death, after all, which does sieve fitness quite fine. The exact same applies to cognition – some capability of tracking food resources, or telling stories to entice the girls, or whatever – is more likely to be rewarded with propagation into the next generation the more reliably it tracks reality.

The only way Plantinga can avoid the reality of environmental selection tending to enhance cognitive reliability is by pretending his bizarre example – Paul wanting to pet the tiger while believing that the best way to pet it is to run away from it – might equally likely evolve. Well, he’s certainly correct that that would not be reliable cognition! But he’s so stupid about evolution that I am continually amazed anyone ever takes him serious as a “thinker”.

He might put it in more sophisticated-sounding language but all Planting boils down to is the same as Ken Ham: “I ain’t no monkey” and “monkeys don’t have souls anyways”.

Oh, ha! Tumblr provides better* philosophy than Plantinga:

.

.

.

.

* where “better” is defined pretty much any way you wish: more important, more interesting, more understandable, well-aligned with observable reality, unbiased, not crippled by christian presupposition …

I’d be interested in some of those many, many criticisms of that argument. Two examples, please.

If you set out to find the ground of being or the necessary being and you end up with the universe, then you went astray somewhere, because the universe as the sum of all objects and things is the stock example of contingency, not of necessity. The other option is that you actually did not set out to find the ground of being, but you are up to something else instead.

Also, if you ascertained the ground of being and then you tried to deduce its characteristics, you’d find it logically impossible to prove that it’s something less or other than God. If you think it possible that the ground of being or a necessary being is something else, show it. “The universe” is the wrong answer here. “Pantheism” may be a bit better, depending on the formulation.

Just mentioned this in another thread but as it has cropped up here let me say I have no problem accepting the various arguments for a creator based such as deveoped by/from Aristotle, Aquinas, Craig, Plantinga, Feser etc as equal to any other explanation for the existence of our universe. But where does that get us, other than to a creator whose sole attribute is “created this universe”? Every other attribute of such a creator is added on by human inventors.

How do we bridge the gap between creator and dogma other than by human invention?

@Alan Fox

How does this reply to my question about the criticism of Plantinga’s EAAN argument? I guess it was not meant to. However, I am still interested in having at least two examples of criticism of Plantinga’s EAAN.

If you think that (the nature of) existence is a human invention in the sense that you can make up whatever you want, then you won’t bridge the gap. If you accept that (the nature of) existence is something that can be ascertained with certainty, that the proof of rightness or wrongness of your conclusions can be determined by means of thorough observation and integral experience, then you can bridge it. Then again, if you think thorough observation and integral experience is just something we humans invented for no real purpose, then you have no concept of dogma, truth, fact, etc. and you won’t bridge the gap.

johnnyb,

But isn’t the Blyth Institute just johnnyb?

I’m a pragmatist and an empiricist (I think 🙂 ). Pragmatically, I accept what we, as humans collectively, have managed to ascertain about our existence and the existence of observable reality is valid. Speculation about what it means is free and available to all.

Observation and shared experience is the key to understanding.

Not sure what you mean by “integral”. “Shared” works for me.

I think humans tend to be purposeful rather than purposeless and most human invention was done for a purpose and has a purpose. Of course the intended purpose and the resultant purpose may be different.

Well, indeed, dogma and truth are two tricky concepts for me, Dogma especially. Which was what I’m getting at regrading the gap between accepting for arguments sake that a creator created this universe and attributing various dogmas or purpose to that creator. How else do we come up with this stuff other than by inventing it?

The way I see it, these are the two key points of departure between you and I. If the relevant experience is merely “shared” to you, then your concepts of fact and truth, as derived from shared experience, are whatever the majority (or weighted statistical average Joe) says they are. For me, fact and truth are absolutely independent from what people say they are. The majority does not necessarily have a relevant concept of fact and truth. Fact and truth are matters of logic and experience, and there evidently are people with deficient logic and experience, and there are ways to determine when logic and experience are deficient. When your perspective is integral and holistic, you will find out the deficiencies.

And in my previous post I was getting at this: When you don’t have a serious enough concept of creator and dogma, other than just “for the argument’s sake” or for the sake of ridicule or idle speculation, then your question is not serious enough to merit uttering. It certainly does not merit a response. In order to merit a response, it should contain clear and relevant concepts so that your interlocutors would have sufficient certainty as to what they are responding to.

You have appointed yourself omniscient.

What I mean by shared experience is accumulated experience – the total of human knowledge. The thing about observation is that anyone can do it. Anyone with enough time and resources can repeat scientific observation and experiment. Many false conclusions and results have been exposed by repeat experiments. No weight of opinion will make water run uphill.

I’d definitely agree with half of that statement.

This site endorses voluntary participation. You are under no obligation to respond to my query. I still wonder how anyone gets from, say, Plantinga’s proof of God to the nature and attributes of God without making up the dogma.

That is almost Murrayesque in opacity.

Yeah, it’s bizarre.

It’s so self-aggrandizing and un-self-reflective at the the same time. All you peasants, too dumb to know that the truth is out there, floating in space uncontaminated by your grubby average minds, and I alone am the wise one with access to ultimate truth.

I know that’s not exactly what Erik said, and it’s possible that’s not exactly what he meant.

But why else would he so contemptuously dismiss the collective wisdom of humanity?