In today’s post, I’m going to chop down two of Professor Feser’s proofs for God’s existence at the roots: namely, his first proof (in which Feser argues for the existence of a purely actual Being) and his second proof (in which he endeavors to show that an absolutely simple Being exists). Among Feser’s five proofs, his first proof has a special preeminence, as Feser uses it to deduce other attributes of the purely actual Being – its unity, immutability, eternity, immateriality, incorporeality, perfection, goodness, omnipotence and omniscience – which, taken together, warrant it being called “God.” Feser’s second, third, fourth and fifth proofs borrow from the arguments developed in Feser’s first proof, when deducing these same attributes, so if it turns out that the arguments Feser puts forward for these attributes rest on flawed assumptions (as I’ll show they do), then all five of Feser’s proofs of God will be flawed, in their conclusions at least.

So what’s wrong with Feser’s first two proofs? Feser’s first proof is flawed on two counts: first, his attempt to establish the existence of a Being Who is purely actual and in no way potential only manages to establish the much weaker conclusion that there exists something which doesn’t need anything outside it to “hold it together” as a being, and which doesn’t need to be “switched on” (or actualized) by anything else, either in order to exist, or in order to ground the existence of other things – a description which could apply to material objects. Additionally, Feser’s argument that there cannot be more than one purely actual Being is badly flawed, as it trades on an ambiguity in the words “privation” and “lack”: not having a perfection is only a defect if having that perfection is part of one’s nature. (A bird that lacks wings is deficient; a man who lacks wings is not.)

Feser’s second proof of God’s existence, which argues for the existence of an absolutely simple Being, is equally flawed – in this case, by bad mereology. (Mereology is the branch of philosophy which deals with parts and wholes.) Incredibly, nowhere in his proof – indeed, nowhere in his entire book, or in any of his other books – does Feser even bother to define what it means for something to be a part of a whole, and in any case, his argument proves much less than Feser would like it to: all it shows is that there is a Being whose essence is not composed of parts that are ontologically prior to the whole they comprise. However, even a Being with a simple essence could (if it is a personal agent) nonetheless have properties, extrinsic to His essence, which He freely generates by Himself, when creating things. Alternatively (if it is an impersonal entity), it might have other properties which arise from its essence and are therefore ontologically posterior to its essence. In any event, neither of Feser’s first two proofs demonstrate the existence of a Being which is distinct from the material world, and for this reason, they cannot take us to God.

What about Feser’s remaining proofs – his third, fourth and fifth arguments? Unfortunately, in order to arrive at the conclusion that there is a God (and not just a First Cause), they all rely on the critical assumption (which Feser fails to justify) that the First Cause is purely actual. For that reason alone, they fail as proofs, in their current form. Whether a revamped version of these arguments can succeed in establishing the existence of God is a topic I’ll discuss in a future post.

Readers may be wondering why I, as a religious believer, am attacking Feser’s first two proofs with such gusto. My reasons can be summed up in four words: Divine and human freedom. If you accept Feser’s argument that there exists a purely actual, absolutely simple Being, then two things follow: first, you have no more freedom than a character in a novel does, which means that your Maker cannot hold you morally accountable for your misdeeds, even if other people do; and second, the Being Who created you lacks the capacity to make free choices (scroll down to section 4, on God’s Will), as it has no potentialities which it is capable of realizing. I’ve explained why these conclusions follow from Feser’s arguments in my previous posts (see here and here), so I won’t repeat myself here. Since I believe that we are morally accountable for our actions to everyone (including God), and since I believe that God would have had to actualize His potential to create – something Feser says a purely actual Being cannot do – when He freely chose to make this world, then I have a strong interest in discrediting Feser’s first two proofs of God’s existence, as someone who believes that both God and and human beings possess genuine, libertarian free will.

Before I continue, I’d like to say that I have the greatest respect for Professor Feser, despite my differences with him. In any vigorous academic controversy, there is always the potential for mutual misunderstanding, so I would like to state here that I have made every effort to represent Feser’s views (and his reasons for holding them) as accurately as possible. If Dr. Feser notices any inaccuracies, then I would welcome his correction.

As today’s post will be a lengthy one, I’ve decided to set up a main menu, which will allow readers to navigate their way backwards and forwards with total freedom, when perusing it.

===================================================================

A. INTRODUCTION

RETURN TO MAIN MENU

1. The centrality of Feser’s first proof: how all his other proofs rely on it

Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral at dusk. Note the flying buttresses, which uphold the tall central pillar. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Feser’s five proofs for God’s existence are by no means independent of one another: rather, they resemble a single tall pillar, which is supported at its base by four additional buttresses. What I intend to show here is that the pillar itself is an Aristotelian one: Feser’s proofs all deduce key attributes of the Being they end up calling “God” from the Aristotelian premise that a purely actual Being exists. Without this premise, Feser’s arguments are incapable of taking us to a Being whom we would call God. The following brief excerpts from Feser’s second, third, fourth and fifth proofs of God’s existence will serve to illustrate my point.

In his formal statement of his second, Neo-Platonic proof, Feser includes the following premise, which harks back to his first, Aristotelian proof of God’s existence:

35. A purely actual cause must be perfect, omnipotent, fully good and omniscient. (2017, p. 82)

In his formal statement of his third, Augustinian proof, Feser once again includes a premise which appeals to conclusions reached in his Aristotelian proof of God’s existence:

26. What is purely actual must also be omnipotent, fully good, immutable, immaterial, incorporeal, and eternal.

In his fourth, Thomistic proof, after having established the existence of a Being Who is Pure Existence itself, and after having deduced that such a Being must be purely actual, Feser then invokes conclusions previously reached in his Aristotelian proof:

33. Whatever is purely actual must be immutable, eternal, immaterial, incorporeal, perfect, omnipotent, fully good, intelligent, and omniscient.

Finally, in his fifth, Rationalist proof, after having argued for the existence of a necessary Being, and after having reasoned that such a Being would have to be purely actual, simple and identical with its own act of existence, Feser draws upon the Aristotelian proof one last time, in order to deduce additional divine attributes:

Something which is purely actual, absolutely simple or non-composite, and something which just is subsistent existence itself must also be immutable, eternal, immaterial, incorporeal, perfect, omnipotent, fully good, intelligent, and omniscient.

The upshot of all this is that if Feser’s Aristotelian argument for a purely actual Being is shown to be flawed, then Feser’s five proofs provide us with no reason for thinking that an immutable, eternal, immaterial, incorporeal, perfect, omnipotent, fully good, intelligent, and omniscient Being exists – and hence, no reason for thinking that God exists. Without a revamp, they all fail.

===================================================================

B. FLAWS WHICH UNDERCUT FESER’S FIRST PROOF

Summary of My Argument: In this section, I’ll be arguing that Feser’s first proof of the existence of God is flawed on two counts: it fails to establish the existence of a Purely Actual Being, and it fails to show that such a Being must be unique. As we’ll see, Feser’s argument for a purely actual Being requires the existence of a hierarchical series of efficient causes, each of which actualizes the existence of its effect, and the examples he cites in his book don’t fit this description: either they’re material causes (rather than efficient ones) or they don’t actualize the existence of their effects, but merely hold them in place. In any case, all Feser’s philosophical argument demonstrates is that there exists a First Actualizer which does not require anything else in order to exist, or in order to ground the existence of other things. Feser’s attempts to show that such a Being must be utterly devoid of all potentialities, even with regard to the activities which it is capable of performing, turn out to rely on vaguely worded metaphysical principles and questionable assumptions about parts (which I’ll discuss further in section C), which Feser does not justify. Even worse, Feser’s argument for the uniqueness of this purely actual Being rests on faulty logic, as it trades on an ambiguity in the terms “privation” and “lack,” which may denote either a perfection which a being does not have, or one which a being could and should have (i.e. an unrealized potential, which no purely actual Being would possess). Since the aim of Feser’s first proof is to show that there exists one and only one purely actual Being, and to then use its pure actuality as a springboard to deduce this Being’s other attributes (which make it worthy of being called “God”), I am forced to conclude that Feser’s first proof of God’s existence is irremediably flawed.

RETURN TO MAIN MENU

2. The logic of Feser’s argument for the existence of a First Actualizer

Feser’s argument for the existence of an Ultimate Actualizer (2017, pp. 35-36) can be divided into two parts: first, he attempts to establish that any change occurring in the world requires an actual cause (premises 1 to 5), and then he proceeds to argue that any change has to take place within some thing, or substance, whose existence presupposes the existence of a purely actual Being (premises 6 to 15).

A short note on Feser’s first five premises

Radioactive decay, such as the alpha-decay of a Pb-210 atom into an atom of Hg-206, is often (mistakenly) held to be an example of an uncaused change. Image courtesy of Inductiveload and Wikipedia.

To give credit where credit is due, I have to say that Feser’s discussion of change in his book is very thorough: he forestalls all of the objections that have been raised against Aristotle’s argument for the existence of an Unmoved Mover (or as Feser would prefer to say, an Unactualized Actualizer).

The most fundamental objection that could be made to any such argument is to deny the reality of change itself. Feser responds to the “block universe” objection (based on Minkowski’s interpretation of Einstein’s theory of relativity) that in a four-dimensional universe where time is treated as just an extra dimension, change is an illusion, by pointing out that even if the theory of relativity can account for physical change without having to treat it as objectively real, it still fails to rule out the occurrence of psychological change (e.g. when someone who was previously skeptical of the theory of relativity comes to believe it is true). This rebuttal amounts to a “Cartesianization” of Aristotle’s argument: if I can be deceived about the occurrence of change, then my being undeceived is itself a change. In effect, this reduces Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover to the status of an Undeceived Deceiver (or Undeceiver)! Much more apropos is Feser’s second rebuttal of the “block universe” objection: even if change turns out not to be objectively real, the actualization of potential certainly is, because the very existence of a thing (such as a body) involves the actualization of its potential. (For instance, if the body is composed of parts, then these parts have the potential to disintegrate: in other words, the body is capable of non-existence.)

Feser addresses the objections that Newton’s First Law of Motion makes no mention of causes, and that quantum mechanics does away with causes at the submicroscopic level, by pointing out that these are purely mathematical descriptions of reality, which make no attempt to capture the notion of a cause (2017, pp. 51-54). So far, so good. However, with regard to Newton’s First Law, I think Feser would have been better off arguing that what Newton really showed was that a change in a body’s position, as such, is not a real change in the body itself, which needs some Actualizer to bring it about: rather, it is only a change in a body’s velocity that needs to be accounted for, in terms of the external forces accelerating that body. An Aristotelian might object that even when a body moves through space at constant velocity, it will still (eventually) come under the influence of forces that were not acting on it previously, as it approaches other bodies – but in that case, the body’s velocity will change, and that (not the body’s moving at constant velocity) is what we need to account for. The key point here is that there is no need to regard a body’s movement at constant velocity as a new actualization of its potential, which needs to be explained by some Actualizer. Only acceleration requires such an Actualizer.

With regard to radioactive decay, which is often held to be uncaused, Feser argues that even if it is a non-deterministic event, it still requires a cause. That cause, he suggests, may be either the thing that originally generated the atom which is now decaying (a bad move, in my opinion, as it pushes the cause back into the distant past) or “whatever it is that keeps the … atom in existence here and now” (2017, p. 55). The latter suggestion makes more sense, but it seems to me that Feser could have simply appealed to the existence of the quantum vacuum at this point: radioactive decay is caused by the tunnelling of a particle out of the nucleus, which in turn occurs because the particle is able to borrow energy from the surrounding quantum vacuum: this borrowed energy can thus be described as the efficient cause of the nucleus’s decay. Likewise, virtual particles (which randomly fluctuate into and out of existence over very short periods of time) do not arise out of nowhere, but out of the quantum field which they are associated with; this field may therefore be called their efficient cause.

Feser also successfully addresses the scientific objection that there is always a slight time delay between cause and effect by pointing out (2017, pp. 61-62) that there is no such time delay when the cause and effect are contiguous (e.g. when the throwing of a brick breaks a glass, or when a stick moves a stone which it makes contact with), because in these cases, what we have are not two “loose and separate” events with no “necessary connection” holding between them (as Hume famously envisaged), but rather, two parts of one and the same event (e.g. the brick’s smashing of the glass, or the stick’s impact on the stone) – namely, the cause’s bringing about of the effect. And even if this event takes place over a short interval of time, this in no way undermines the claim that the cause and effect are simultaneous; all it shows is that the action of the cause is not instantaneous.

Einstein’s theory of relativity is sometimes invoked as an objection to the notion that a cause and its immediate effect are simultaneous, as the simultaneity of two events depends on the observer’s frame of reference, according to Einstein’s theory. Feser smacks down this objection by noting that the relativity of simultaneity only applies to two spatially separated events, whereas in the case we are considering, there is one event occurring at a single spatial location (2017, p. 63). Hence the objection is irrelevant.

All in all, Feser does a pretty good job of rebutting the common objections to Aristotle’s Argument from Motion, but in doing so, he transforms it into an entirely different kind of argument: no longer is it an argument about change but about being, instead. On Feser’s rendition of the argument, it is the actualization of being which needs to be explained. Which is all well and good: but that then renders the first five premises of Feser’s argument redundant.

A curious feature of Feser’s Aristotelian proof: the first five premises are redundant!

One of Feser’s favorite examples: a coffee cup resting on a desk.

Feser spends the first five pages of his Aristotelian proof (2017, pp. 17-21) trying to establish that change is an objective feature of the world, and that changes requires a changer, plus no less than 15 pages rebutting objections relating to allegedly uncaused changes occurring in the natural world, as well as accusations that his proof is based on outdated science (2017, pp. 46-60). So it is quite astonishing when Feser abruptly changes gear on page 21, and invites his readers to consider instead the example of a coffee cup resting on a desk (which is supported by the floor, the foundation of your house, and ultimately the Earth itself), in order to illustrate the notion of a hierarchical series of causes, whose members possess only derived causal power, with the exception of the first member, whose causal power is built-in or inherent (2017, p. 24). Feser explains that what is really significant in this illustration is that potentials are being actualized, even if no change occurs, and he confesses that the examples which he used of change, earlier on in the chapter, were intended merely to convey to readers the idea of a potential which is incapable of actualizing itself:

What we call a hierarchical series of causes is quite different. Here every cause other than the first has its causal power only in a derivative way. Thus the desk, floor and foundation have no power to hold aloft the coffee cup except insofar as they derive it from the earth this whole series rests on. This takes us beyond what we would ordinarily think of as change, because we would ordinarily think of the sequence of the cup, desk, floor, foundation, and earth as simultaneous. But what matters is that we still do have the actualization of potentials, the notion of which was introduced as a way of making sense of change. The potential of the cup to be three feet off the ground is actualized by the desk, the desk’s potential to hold the coffee cup aloft is actualized by the floor, and so forth. (2017, p. 25)

We can therefore safely ignore the first six premises of Feser’s argument, which conclude that change is caused by something already actual (premise 5), and that the occurrence of any change C presupposes some thing or substance S which changes (premise 6). For Feser’s argument, in the end, is not about change, but about being: what he is trying to show is that there is a Thing (or Being) which actualizes the potential for existence of all other things, and that this Being is itself purely actual. And in order to do that, he doesn’t need to invoke the occurrence of change in the world; all he needs to point out is that some things (or substances) have the potential not to exist – which implies that they also have a potential to exist, which is currently being actualized (obviously, or they wouldn’t be here).

A response to an objection raised by Bradley Bowen

Christine Jorgensen (born George William Jorgensen Jr.), the first person to become widely known in the United States for having sex reassignment surgery. Jorgensen’s sex change surgery creates an apparent difficulty for Feser’s account of change as the actualization of a potential, if we define “potential” as a natural tendency, as the physical change wrought by sex change surgery is not realizing a natural tendency: it requires radical human intervention. Image courtesy of Maurice Seymour and Wikipedia.

Over at the Secular Outpost, philosopher Bradley Bowen objects (see here and here) that the terms “potential” and “thing or substance” are not properly defined by Feser, in premise 6 of his argument. Bowen’s objection is a very powerful one, but I think it can be met. So on Feser’s behalf, I’d like to propose a definition of “substance“: a particular entity with causal powers – specifically, a mind or a material entity (e.g. a physical object, or an agglomeration), or even a mental content (e.g. a thought, a memory, or an afterimage), but not an abstract entity (e.g. happiness) or a generic substance (e.g. sulfur, water or human DNA). On page 75 of his book, Feser approvingly quotes a statement from philosopher William Vallicella’s book, A Paradigm Theory of Existence: Onto-Theology Vindicated (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002, p. 233) to the effect that “everything is either a mind, or a content in a mind, or a physical entity, or an abstract entity,” and he goes on to add that abstract entities are causally inert – which would automatically rule them out as candidates for an Uncaused Cause. Generic substances such as water would be ruled out for similar reasons: not being individuals, they are incapable of causing anything. This agglomeration of water here can (if it is big enough and traveling fast enough) cause a tsunami, but water in general cannot.

On the definition I have proposed above, which I think Feser would endorse, the following entities proposed by Bowen would count as things or substances: God (bearing in mind that for Feser, God is one of a kind), angels, persons, minds, clouds, and even the pain I feel in my right foot, but not coffee (which is generic rather than particular), gravity (ditto), the number three (an abstract object), the color red (ditto, although a red afterimage would count as a thing), space and time (arguably, both abstract objects, and in any case, causally inert). Although coffee and gravity do not qualify as things, this cup of coffee and the Earth’s gravity would certainly qualify as things, on the definition I am proposing.

Regarding the definition of “potential,” Bowen objects that logical possibility is too broad a definition, as it fails to explain why we say that while a hot cup of coffee has the potential to become a cold cup of coffee, it does not have the potential to become chicken soup or gasoline. On the other hand, a definition of “potential” in terms of a thing’s natural tendency is too narrow to cover all cases of change: for example, a person undergoing a sex change operation, or cosmetic surgery, is not realizing a natural tendency in the process, since without deliberate human intervention, that person’s body would never normally develop in the manner which they are trying to achieve. Again, some changes are brought about by sheer luck, rather than any natural tendency: sometimes people who are terrible actors go on to become movie stars, because they just happened to be in the right place at the right time.

But there is an intermediate kind of possibility between logical possibility and the possession of a natural tendency: physical possibility. And in a comment made on January 6, 2018, Bowen agreed that “[p]hysical possibility does seem like a close match to what Feser has in mind.”

I suspect, however, that Feser’s definition is somewhat broader than physical possibility, and that he would want to include metaphysical possibility as a kind of potential, since he would not wish to rule out in advance the existence of immaterial minds, such as angels, to whom the concept of physical possibility would not apply. Such minds might even be capable of performing feats which are physically impossible, but not metaphysically impossible: for instance, they may be able to lower the entropy of a closed system, or perhaps even turn a rod into a snake (to recall one of the more colorful miracles narrated in the book of Exodus, which even Pharaoh’s magicians were said to be capable of duplicating), but not to take human beings back into their own past (a metaphysically absurd scenario that gives rise to Einstein’s famous “grandmother paradox”). It is worth noting that Feser’s Aristotelian argument for God’s existence makes no advance commitment to the existence of immaterial minds; but by the same token, he would certainly not wish to rule them out, either.

Feser’s nine-step argument for a purely actual actualizer

A visual proof of Pythagoras’ Theorem. Image courtesy of William B. Faulk and Wikipedia.

We can now jettison premises 1 to 6 of Feser’s Aristotelian proof for God’s existence, and proceed instead from the premise: Let S be some thing or substance, understood as a particular entity with causal powers. We’ll call this premise 6A. Feser’s nine-step argument for the existence of a purely actual actualizer goes as follows:

[6A. Let S be some thing or substance – i.e. a particular entity with causal powers.]

7. The existence of S at any given moment itself presupposes the concurrent actualization of S’s potential for existence [where “potential” signifies “metaphysical possibility.”]

8. So, any substance S has at any moment some actualizer A of its existence.

9. A’s own existence at the moment it actualizes S itself presupposes either (a) the concurrent actualization of its own potential for existence or (b) A’s being purely actual.

10. If A’s existence at the moment it actualizes S presupposes the concurrent actualization of its own potential for existence, then there exists a regress of concurrent actualizers that is either infinite or terminates in a purely actual actualizer.

11. But such a regress of concurrent actualizers would constitute a hierarchical causal series, and such a series cannot regress infinitely.

12. So, either A itself is a purely actual actualizer or there is a purely actual actualizer which terminates the regress that begins with the actualization of A.

13. So, … the existence of S at any given moment presupposes the existence of a purely actual actualizer. [Feser actually writes: “the occurrence of C and thus the existence of S,” but as we’ve seen, the argument still stands, even if we remove mention of any change C.]

14. So, there is a purely actual actualizer.

Feser’s fallacy

That’s Feser’s argument for a purely actual actualizer, in a nutshell. The metaphysically controversial premises are premises 9 and 11. As I’ll explain below, I accept premise 11, but I think premise 9 is mistaken, because it poses a false dichotomy: instead of saying that the actualizer A’s own existence presupposes either (a) the concurrent actualization of its own potential for existence or (b) A’s being purely actual, we should say that it presupposes either (a) the concurrent actualization of its own potential for existence or (b) A’s not having a potential for existence that needs to be actualized. On the second alternative, A would need nothing outside itself to hold it together as a being, and A would not need to be “switched on” (or actualized) by anything else, either in order to exist, or in order to ground the existence of other things. However, A’s not having a potential for existence that needs to be actualized is not the same as A’s being purely actual – a point which undercuts Feser’s attempts to deduce the attributes of the Uncaused Cause from its being purely actual. For all we know, a being whose existence does not need to be actualized by anything else might turn out to be a material object, and nothing more – for example, a quantum field, or something like that.

To his credit, Dr. Feser is aware of this objection, and tries to rebut it in his book. Below, in section 4, we’ll examine Feser’s attempts to show that a Being whose essence is purely actual must also be actual in every other respect, and why these attempts are unsuccessful.

===================================================================

RETURN TO MAIN MENU

3. What Feser gets right and wrong about infinite regresses and hierarchical causal series

Why hierarchical causal series require a first cause

For the record, I happen to think Feser is right in distinguishing between hierarchical causal series (where the intermediate members of the series exercise causal power in a purely derivative sense) and linear causal series (where each member exercises causal power in its own right – Feser gives the example of coffee in a cup being cooled by the surrounding air, which has been cooled by the air conditioner, which was turned on earlier by you). Feser points out that linear causal series don’t need a first member. To cite a well-worn example from Aristotle: sons are sired by their fathers, who are sired by their fathers, and for all we know, this may have been going on for all eternity. However, Feser insists that since the intermediate causes in a hierarchical series possess their power in a purely derivative sense, this kind of series requires a first member that possesses causal power inherently – for if there were no such member, the series as a whole would possess no causal power whatsoever. That doesn’t necessarily mean that a hierarchical causal series needs to come to a terminus at some point: Feser is willing to allow (2017, p. 24) that the first member of the series, rather than being at the top of a finite series, could equally well be standing outside an infinite series of hierarchical causes, directly imparting causal power to each member of the series.

Why Feser’s coffee cup is not a hierarchical causal series, and why that matters

Latte, with latte art, in a 12 oz. ceramic mug. Courtesy of Coffeecupgals and Wikipedia.

One of the examples Feser draws upon in his argument for a purely actual Being is that of the coffee in a cup, which depends for its existence on the various substances which make it up, such as water, which is in turn dependent on its constituent hydrogen and oxygen atoms, which in turn depend on the subatomic particles that make them up.

What I would like to point out here is that while the series is indeed hierarchical, it is not a causal series, in the sense required by Feser, which corresponds to what Aristotle called an efficient cause. Recall that in Feser’s argument, each cause actualizes the existence of its effect – in other words, it does something to bring it about. That is precisely what an efficient cause does: it’s a “doing” cause, just as a verb is a “doing” word (most of the time, anyway). And in ordinary English parlance, whenever we speak of A as being the cause of B, we mean the efficient cause. Feser appears to acknowledge in his book (2017, p. 55) that the causal series he has in mind is a series of efficient causes, when he refers to “whatever it is that keeps the Pb210 atom in existence here and now” as a “deeper efficient cause.”

However, the dependence of coffee upon its chemical constituents is a dependence of a different sort, which Aristotle referred to as material causality. A material cause can be defined as the matter or substance which constitutes a thing which is being changed, or otherwise actualized. For a table, that might be wood; and for the coffee in a cup, that would be the various chemicals (including water) which make up the coffee. Unlike an efficient cause, which is external to the thing it actualizes, the material cause is internal: it is simply the substrate underlying the thing’s actualization.

The first point I wish to make here is that a hierarchical series of material causes might turn out to be infinite: the coffee in a cup could be dependent on its various chemical constituents, which are dependent on the atoms of which they are composed, which are in turn dependent on the subatomic particles that comprise them, and so on ad infinitum. The supposition that a lump of matter is divided into infinitely many parts may strike many people as uncongenial, but unless we accept the traditional arguments against the possibility of an actual infinite (and Feser himself is somewhat agnostic about these arguments, which he nowhere appeals to in his book), then it seems we cannot exclude this possibility.

The second point I’d like to make is that Feser’s argument for a purely actual Being requires the existence of a hierarchical series of efficient causes, each of which actualizes the existence of its effect. It is this kind of series which Feser argues cannot be infinite, as it requires an ultimate member which possesses causal power in its own right. But in a series of material causes, the various component parts do not exercise any causal power upon the whole which they comprise: for instance, the hydrogen and oxygen atoms in a water molecule may act upon each other, but they do not “act upon” the molecule as a whole. Because the various components of a thing, at any given level, do not exercise causal power upon the next level up, there is no need to postulate an ultimate source of their causal power, such as a “bottom level” of material reality. There might be one, and there might not. We don’t know.

The upshot is that the illustration of the coffee in a cup doesn’t help Feser’s case. We need to find a better illustration. Feser provides two illustrations which are valid examples of efficient causality, but as we’ll see, they don’t help his case, either.

Coffee cups,lamps and supports

Feser uses the example of a lamp above your head, which is held up by a chain, and ultimately by the Earth, to illustrate his argument that a hierarchical series of causes must have a first member, which possesses causal power in its own right. Image courtesy of Kyle Pearce, Slick Lighting and Wikipedia.

Feser appeals to two examples to bolster his case that an infinite regress of concurrent actualizers requires a first member: first, a coffee cup resting upon a desk, which is supported by the floor, which is in turn supported by the foundation of a house, which is supported by the Earth itself; and second, a lamp above your head, which is held up by a chain, which is held up by a fixture screwed into the ceiling, which in turn is held up by the walls of your house, which are supported by the foundation, which is held up by the Earth. Neither of these examples helps Feser’s case.

First, let us suppose, as Feser does, that the series of causes is indeed a hierarchical series. Even if that were true, Feser himself admits in his book (2017, p. 26) that they do not constitute examples of one thing maintaining another thing in existence: as he puts it, only in the case we discussed above, of the coffee in the cup, is it “the very existence of a thing that is at issue rather than merely its particular location.” The desk on which the coffee coup rests keeps it here, but it does not keep it in being. The same goes for the chain that holds up the lamp above your head.

Second, careful consideration of the two examples cited by Feser reveals that each of them is actually a linear causal series, as far as the actual exercise of causal power is concerned. At first blush, it might seem as though what the desk does to the coffee cup it supports is to provide a stable surface for it to rest on. Likewise, what the chain does is to provide a stable attachment for the lamp connected to it. But while these expressions accurately describe the function of the desk and the chain, they don’t tell us what action each performs, in order to carry out this function: “providing stability” is not the name of an action as such. Now, however we describe this action (and I don’t wish to get technical here), the important point is that it is carried out by the molecules at the interface between the supporting object and the object it supports. The key point here is that molecules do not derive their causal powers from anything else in the cosmos – and certainly not from the Earth. For instance, the molecules on the surface of the desk hold up the coffee cup by virtue of their electrostatic properties, which they possess inherently. And when each of the members of a causal chain exercises causal powers in its own right, then what we have is a linear causal series, not a hierarchical one.

It is of course true that if the foundation of the house were suddenly to disappear, the desk would no longer support the coffee cup, and the chain would no longer hold up the lamp. But it would be a mistake to infer from this fact that the foundation is doing something to the desk and the coffee cup, or to the chain and lamp, to keep them in place. It isn’t acting on any of these things. All that the foundation interacts with are the surfaces in contact with it: namely, the floor and the walls. Likewise, it would be a mistake to think that the foundation of the house somehow transfers causal power to the desk, via the floor, or that it transfers causal power to the chain via the walls, ceiling and light fixture. There is no “transfer” here: for what exactly is it that’s supposed to “pass through” the walls and the floor to the lamp and the coffee cup? Some flow of energy, perhaps? Then why can’t we measure any such mysterious flow? And how does it manage to pass through insulated material? Is it gravity, then? But in that case, it needs no intermediate causes: the Earth alone is massive enough to do the job, and it certainly doesn’t attract a coffee cup by imparting some mysterious downward-pulling power to the foundation, floor and desk upon which it rests.

What I am suggesting is that in the examples cited by Feser, we have been misled by the way we ordinarily describe what’s going on, into thinking that some kind of occult “causal power” is traveling from the Earth to the lamp and the coffee cup. In fact, there is no transmission: indeed, even to call it a linear causal series is incorrect. Rather, what we have here is a set of entirely separate cause and effect pairs (namely, the surfaces which happen to be in contact with one another), which, taken as an ensemble, do a pretty good job of holding up the coffee cup and the lamp.

The foundation falls away: do Feser’s two causal series really behave like linear causal series?

A lodestone, or natural magnet, attracting iron nails. The magnetized nails can in turn pick up other nails, or iron filings. What’s interesting is that the nails retain their magnetism for a short while, even when the magnet is removed. Image courtesy of Fred Anzley Annet and Wikipedia.

Feser may object that whereas in a linear causal series, the members of the series will continue acting even when the earlier members of the series cease to do so (e.g. the air conditioner will keep working even if the person who switches it on suddenly dies of a heart attack), this is not the case for the two examples he cites: take away the foundation of the house, and the coffee cup and lamp will both fall from their present positions. But here, I think Feser is making a false generalization. For a linear series of causes, it is not always the case that the removal of an earlier cause will leave the operation of subsequent causes unimpeded. Even in a linear series, the sudden removal of one member of the series may cause subsequent members of the series to lose their inherent causal power almost immediately. In Feser’s own illustration of a linear series, if the air conditioner stops working, the air in the room will eventually heat up again, warming the coffee. And there are much better examples: think of a magnet which picks up a nail, which in turn attracts some iron filings. For a brief time, the nail’s power to attract iron filings is inherent (albeit very weak and evanescent), as shown by the fact that if the magnet is suddenly removed, the nail will remain magnetic for a short while, and will continue to attract the iron filings. Here, then, we have a linear causal series, where the removal of a cause higher up the chain (namely, the magnet) has an almost immediate effect, further down the chain. And so it is with the desk on which the coffee cup rests: if the foundation of the house supporting the desk is suddenly removed, it will start to fall almost immediately.

This is very important, for it has bearing on my next point: namely, that the kind of hierarchical causal series which Feser requires for his argument to work, cannot exist in the natural world.

Why simultaneity matters

While Feser allows (2017, p. 24) that even a hierarchical causal series might be infinite in length, with the First Cause standing above all the intermediate members and sustaining each of them, he does not rule out the possibility that the first member of a hierarchical causal series may turn out to be a remote cause, at the top of a very long but finite series. This is an important point, because Feser is emphatic that the first cause is no mere Initiator – a first cause that may have kicked the bucket long before its ultimate effect is brought into being – but a very actively involved concurrent cause, as he insists in premise 9 of his argument. As he puts it (2017, p. 28): “for a thing to exist at any particular moment requires that it be actualized at that moment, at least if it is the sort of thing which has the potential either to exist or not to exist.”

In order for the first member of a very long hierarchical series to be concurrent with its ultimate effect, it isn’t enough, as Feser appears to suggest on pages 60 to 63 of his book, that the First Cause’s act of bringing about the effect take place over an interval of time rather than an instant: for it could still be the case that the action of the First Cause takes place over the time interval from t0 to t1, while the occurrence of the ultimate effect in the series takes place over a later time interval from t2 to t3, which would mean that the First Cause may or may not still exist when the effect occurs: it might have dropped dead or vanished into thin air. This is precisely the kind of scenario Feser wants to rule out, in the case of a hierarchical causal series.

Fishermen’s boat stranded in Kallady, Sri Lanka, by the 2004 tsunami. The tsunami which hit Sri Lanka was caused by a magnitude-9.2 earthquake that occurred in Aceh, Indonesia, two hours previously. The quake itself lasted no more than ten minutes.

Nor will it help to assert, as Feser does (2017, pp. 62-63) that the links in a hierarchical causal series all form part of one big event: even if that were so, it in no way entails that the various causes contributing to the event all overlap in time. Maybe they will and maybe they won’t. For that matter, you could describe the approach of a tsunami from hundreds of kilometers away as one “big event,” but the earthquake which triggered it may be over, by the time the tidal wave generated hits the remote shore (see the picture above, which depicts the result of the 2004 Aceh tsunami, generated by an earthquake which lasted no more than ten minutes but generated a tidal wave that took two hours to reach Sri Lanka). So while Feser may be correct in writing that “what makes a causal series hierarchical than linear is not simultaneity per se, but rather the fact that all the members in such a series other than the first have their causal power have their causal power in a derivative or instrumental rather than inherent or ‘built-in’ way” (2017, p. 63), it seems to me that he is still committed to the simultaneity of cause and effect, in a hierarchical causal series. Thus if the action of the First Cause were to take place over a time interval from t0 to t1, the occurrence of the ultimate effect in the series would have to take place over the same time interval, from t0 to t1.

Now, we happen to live in a cosmos where causal influences of any kind take time to propagate over any distance. Since hierarchical causal series require strict simultaneity of cause and effect (as I have argued above), the only such series in the natural world must be very short ones, involving two objects in contact with one another – for example, a ball breaking a window. But even this kind of causality could not possibly allow one object to maintain another object in existence, as the former object is in contact with only the surface of the latter object, leaving the other parts untouched. Within our cosmos, then, it appears that one object never actually maintains another object in existence. (Incidentally, one organism’s transferring vital nutrients to a dependent organism is not the same as maintaining that organism in existence, as (a) it would not perish immediately if the transfer were halted, and (b) the nutrients only benefit it once they are inside its own body, and hence part of it.)

What does that mean for Feser’s argument? As we’ve seen, Feser hasn’t established the existence of a purely actual Being; all he’s shown is that there is some being whose existence does not need to be actualized by anything else. I pointed out above that such a being might turn out to be a material object, and we can now see that material objects are never maintained in existence by other natural objects, in any case. Feser may wish to argue that material objects, whether they be people, pandas, poplars or particles, still require a Transcendent Cause to maintain them in existence, and I believe he is right on this point. But he hasn’t demonstrated that yet, and it is incumbent on him to do so.

Linear causes can be instrumental, too

Dominoes waiting to fall: each is an instrument of the agent who set them up. Image courtesy of Enoch Lai and Wikipedia.

Before I conclude my discussion of hierarchical and linear causal series, I’d like to address the manner in which items in these series can be instruments. In his discussion of hierarchical causal series, Feser writes:

To characterize something as an instrumental cause is … to say that it derives its causal power from something else. (2017, pp. 65-66)

A hierarchical series without a first member would be like an instrument that is not the instrument of anything, a series of causes which have derivative causal powers without anything from which to derive it. (2017, p. 64)

On this point, I believe Feser’s reasoning is sound. However, what Feser overlooks is the fact that the causes in a linear causal series are also capable of being instrumental, if they happen to be finite, and if the first cause in the series is an agent, who is intentionally manipulating the intermediate causes in the series (by skillfully utilizing inherent causal power), in order to bring about some desired effect. An obvious example of such a series is a series of dominoes which are carefully lined up, and then set inexorably in motion by an agent who flips the first one.

Another example (and I know this will shock some readers) is Aquinas’ famous hand-stick-stone series. The important point here is not the finite time delay in the propagation of the impulse through the stick from the hand to the stone. Rather, the point is that the particles which comprise the stick each possess an inherent causal power to propagate an impulse, just as it would propagate, slowly but inexorably, through a series of dominoes that were all lined up. The domino example is just the hand-stick-stone case in slow motion, and agency is equally real in both.

To see why, imagine living in a world with somewhat different laws of nature, where the propagation of an impulse from an agent’s hand through his stick to the stone he wanted to hit took (say) one million times longer than it does in our world, so that the end of the stick that was near the stone responded very slowly to the agent’s push at the other end. In such a world, people would continue to use sticks as instruments, but they would simply adapt to the delay.

I conclude, then, that it is somewhat misleading of Feser to single out the members of hierarchical causal series as instrumental causes, when the same description can apply to members of linear causal series, as well.

===================================================================

RETURN TO MAIN MENU

4. Feser’s flawed argument that the First Actualizer must be purely actual

Many of the Church Fathers likened God to the Sun. God, they said, was purely active and in no way passive. Photo courtesy photos-public-domain.com.

What Feser is trying to establish

In chapter 1 of his book, Feser spells out very clearly what he means when he refers to a purely actual Being – namely, one which could not possibly require actualizing in any way whatsoever, as it lacks any kind of potentiality:

Now since what is being explained in this case is the actualization of a thing’s potential for existence, the sort of “first” cause we are talking about here is one which can actualize the potential for others to exist without having to have its own existence actualized by anything.

What this entails is that this cause doesn’t have any potential for existence that needs to be actualized in the first place. It just is actual, always and already actual, as it were. Indeed, you might say that it doesn’t merely have actuality, the way the things it actualizes do, but that it just is pure actuality itself. It doesn’t merely happen not to have a cause of its own, but could not in principle have had or needed one. For being devoid of potentiality, there is nothing in it that could have needed any actualizing, the way other things do. It is in this sense that it is an uncaused cause, or to use Aristotle’s famous expression, an Unmoved Mover. More precisely, we might call it an unactualized actualizer. (2017, p. 27)

Does a First Actualizer need to be purely actual?

Later in the chapter, Feser rebuts a possible criticism, relating to whether his Aristotelian proof for God’s existence actually establishes that the First (or Ultimate) Actualizer is purely actual, or simply a Being which doesn’t need to be actualized from outside, when it actualizes other beings, but which may nonetheless be capable of being actualized (either by itself or by other beings). The point which is at stake here, as Feser realizes, is that unless he can show that the First Actualizer is purely actual, he will be unable to show that it is one, immaterial, eternal, perfect, omnipotent and omniscient. In other words, an Ultimate Actualizer which isn’t purely actual may not turn out to be God:

…[T]he critic might suggest that even if there is a first actualizer, it need not be a purely actual actualizer, one devoid of potentiality. For why not suppose instead that it has potentialities which are simply not in fact being actualized, at least not insofar as it is functioning as the first actualizer in some hierarchical series of causes? Perhaps those actualities are actualized at some other time,when it is not so functioning; or perhaps they never are. But as long as it has them, it will not be a purely actual actualizer, and thus will not have many of the attributes definitive of God – unity, immateriality, eternity, perfection, omnipotence, and so forth.

To see what is wrong with this objection, recall once again that though the argument begins by asking what explains the changes we observe in the world around us, it moves on to the question of what explains the existence, at any moment, of the things that undergo changes. So, the regress of actualizers that we are ultimately concerned with is a regress of the actualizers of the existence of things. The first actualizer in the series is “first”, then, in the sense that it can actualize the existence of other things without its own existence having to be actualized. So, suppose this first actualizer had some potentiality that had to be actualized in order for it to exist. What actualizes that potential? (2017, pp. 66-67)

This is a very poor argument, as it merely shows that the First Actualizer has no potentiality that has to be actualized, in order for it to exist. What Feser fails to show is that this Being doesn’t possess any potentialities whatsoever. It might still have potentialities which it activates when it acts, for instance.

The same criticism applies to Feser’s argument (2017, p. 67) that if the first actualizer had some potentiality that had to be actualized in order for it to exist, it would have either to be actualized from outside (in which case, the Being wouldn’t be the first actualizer) or from within, by (a) some purely actual part of the Being (which will then be the true first actualizer) or (b) some partly actual and partly potential part of the Being (which generates a vicious regress of actualizers). Feser is aiming at a straw man here: the critic of his argument for a purely actual Being is not claiming that the First Actualizer has some potentiality that needs to be actualized in order for it to exist. Rather, all that it is being proposed is the very modest claim that the First Actualizer has some potentialities which it realizes, in some situations, when it acts. Nothing is being asserted about the needs of the First Actualizer, let alone that it needs anything in order to exist, or in order to ground the existence of other things.

Two more arguments for a purely actual Being, by Feser

In chapter 6 of his book, Feser attempts one more time to prove the existence of a purely actual Being:

… [S]uppose we agree that [the First Cause’s] existence involved no actualization of potential. Might we not still say that its activity involved the actualization of potential? Might we not say that while it had no potentialities with respect to its existence, it does have potentialities with respect to its activity (such as its activity of actualizing the existence of other things)? (2017, p. 185)

Here, at last, Feser is finally addressing his critics’ claims, by focusing on the activities of the First Cause of things. Could the First Cause have potentialities with regard to the acts it is capable of performing? Feser disagrees, for two reasons: first, its actions have to reflect its mode of being, which is entirely active; and second, if it had potentialities, it would be a composite Being, and would therefore require an external cause of its own, to hold it together – in which case, it wouldn’t be the First Cause, after all:

There are several problems with this suggestion, however, one of which might be obvious now that we have set out the principle agere sequitur esse, according to which what a thing does reflects what it is. If the first cause of things exists in a purely actual way, how could it act in a less than purely actual way? How could its acting involve potentiality any more than its existence does? A thing’s existence is, after all, what is metaphysically most fundamental about it; everything else follows from that. In this case we are talking about something whose very existence is purely actual and devoid of potentiality. So, from where in its nature are the (metaphysically less fundamental) potentialities for activity that the critic suggests it has supposed to derive?

Another problem with the suggestion in question is that to say of God that he has potentiality with respect to his activity, though not with respect to his existence, entails that God has parts – a purely actual part, and a part that is a potentiality. Now, as we saw in chapter 2, whatever has parts requires a cause. The reason is that the whole of which the parts are constituents is merely potential until actualized by some principle which combines the parts. This principle cannot be something intrinsic to the thing, for in that case it would be the cause of itself, which is incoherent. So, it must be something extrinsic to the thing… Even if the thing had no temporally prior cause, it would still require an ontologically prior cause. (2017, p. 185)

Neither of these arguments is particularly convincing. Feser’s first argument, if correct, would actually prove too much: it would prove that the purely actual Being is incapable of generating potentialities, even in creatures – for where in His purely actual nature do these potentialities spring from? From creatures’ natures, Feser may reply. Fine: Who is the Author of those?

It gets worse. The purely actual Being is also a necessary Being. If the principle that “action follows being” is correct, then such a Being should only be able to perform necessary actions. It would therefore be unable to perform a contingent action, such as creating (and maintaining in existence) our universe, since such an action would not reflect its mode of being.

Feser’s rhetorical question, “If the first cause of things exists in a purely actual way, how could it act in a less than purely actual way?”, also strikes me as bizarre. For how can an action be anything other than actual? An action is an actualization: it can never be less than purely actual. An action realizes a potential, but that does not make the action itself potential.

Finally, I have to say that the Scholastic principle which Feser appeals to, that “action follows being,” is far from self-evident. From the fact that thing’s existence is more fundamental than its actions, it does not follow that a thing’s mode of action reflects its mode of being, as Feser maintains it does.

Patricia Soltysik, taking part in the April 1974 Hiberina bank robbery, in Noriega St., San Francisco, running out of the bank with a bag of money. Public domain image, courtesy of Wikipedia.

The Scholastic principle that “action follows being” is extremely vague, and as we have seen, there are good grounds for doubting that it is true. Can anything be salvaged from this highly suspect principle, then? I suggest that the core of truth underlying the principle is that the actions we attribute to a thing cannot be at variance with the natural category which it belongs to, as a being. For instance, it would make no sense to say that a cloud robbed a bank, for the actions involved in robbing a bank can only be meaningfully ascribed to an animate being capable of talking and moving at will. Does this revised principle rule out a First or Ultimate Actualizer being able to realize its own potentialities, when it acts? I see no grounds for thinking so.

So much, then, for Feser’s first argument for a purely actual Being. What of the second argument?

Feser’s second argument fares no better, as it simply assumes, without any evidence whatsoever, that if a purely actual Being had potentialities, then it would also have parts. But why need this be so? And what is a part, anyway? Surprisingly, Feser nowhere defines the term, in his entire book.

Suppose now that I make a choice, and in doing so, actualize one potentiality which is open to me as a human being: does it then follow that I and the possibility I chose to actualize are two distinct parts of some greater whole, as if I and my choice were somehow two distinct elements? And if my actions are part of this greater whole, what do we call it? We cannot call it “me,” because that’s what I am, and according to Feser, I am distinct from my actions. But if my actions are not part of me, then what are they part of?

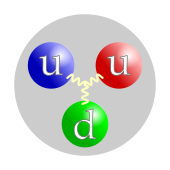

Alternatively, let us consider an utterly impersonal actualization of a potentiality: suppose that a radioactive atom decays randomly, and in so doing, actualize one potentiality which is open to it as a radionuclide: namely, to release excess energy by decaying, rather than retaining it. Would anyone wish to argue that the atom and its act of releasing energy are two distinct parts of some greater whole?

To my mind, it sounds downright bizarre to insist that a thing and its actions constitute a “twosome,” which is greater than the thing itself. This strikes me as a very peculiar way of talking, and Feser needs to justify it.

I conclude that Feser’s arguments purporting to show that the Ultimate Actualizer, or First Cause, must be a purely actual Being, contain question-begging assumptions, as well as some very peculiar assumptions about parts, which Feser needs to explain, before he can possibly hope to convince his readers.

Are there any other arguments for a purely actual Being?

Are there any other arguments for a purely actual Being, in Feser’s book? It turns out that there are a few, very brief arguments, embedded in Feser’s second, third, fourth and fifth proofs. Let us examine each of these in turn.

(a) The Neo-Platonic proof

In chapter two, which argues for the existence of an absolutely simple Being, Feser attempts to show that such a Being would have to be purely actual:

The One also has to be regarded as purely actual rather than a mixture of actuality and potentiality. obviously it has to be at least partially actual, for the reasons set out in the previous chapter – namely, that nothing that is merely potential can do anything, and the One is doing something insofar as it is the cause of all things other than itself. But if it was less than purely actual, then it would be partially potential. In that case it would have parts – an actual part and a potential part – and it has no parts. So, again, it must be purely actual. (2017, p. 76)

Once again, Feser appeals to the hidden premise (for which he supplies no argument) that any being which isn’t purely actual has parts. This assumption makes sense, only if we are talking about something whose existence isn’t fully actual: such a being would indeed have actual and potential elements. However, Feser fails to show why an Actualizer whose existence doesn’t require actualization would still need to have parts, in order to realize some potentiality when acting.

(b) The Augustinian proof

In the third chapter of his book, where Feser argues for the existence of a Mind which contains all concepts and exists of necessity, Feser tries to establish that this Mind would have to be purely actual:

Consider that an intellect that existed of absolute necessity would have to be purely actual. For suppose its existence presupposes the actualization of some potential. In that case its existence would be contingent on such an actualization, in which case it wouldn’t exist of absolute necessity. (2017, p. 106)

The foregoing argument merely shows that the Mind that exists of absolute necessity is purely actual in its Being. However, nothing follows from this fact, with regard to the activities of such a Mind. As far as I can tell, Feser has given us no reason to suppose that it is incapable of actualizing potentials, when it makes choices.

(c) The Thomistic proof

In his discussion of the Thomistic proof for God’s existence in chapter four, Feser explains why a Being which is Pure Existence could not be anything less than purely actual:

As Aquinas emphasized, in a thing whose essence is distinct from its existence, its essence and existence are related as potentiality and actuality. Fido’s essence, by itself amounts only to a potential thing, not an actual thing. Only when Fido’s essence has existence imparted to it is there an actual thing – namely, Fido. Now if essence considered by itself is a kind of potentiality, and existence considered by itself is a kind of actuality, then that which just is existence, that which just is subsistent existence itself rather than merely one derivatively existing thing alongside others, must be purely actual. It could not have some potentiality for existence that needs to be actualized, for then it would not be something which just is existence, but rather merely yet some other thing to which existence must be imparted. (2017, p. 127)

Again, all that Feser has shown here is that a Being which is Pure Existence contains no potentialities within its being. This in no way precludes the possibility that such a Being may be capable of realizing potentialities when it acts.

(d) The Rationalist proof

In chapter five of Feser’s book, where he invokes the Principle of Sufficient Reason to establish the existence of a Necessary Being, Feser argues that this Being must be purely actual:

Why should we think of the necessary being as God? Consider first that, from the fact that it is necessary, it follows that it exists in a purely actual way, rather than by virtue of having potentialities that need to be actualized. For if it had such potentialities, then its existence would be contingent upon the existence of something which actualizes those potentialities – in which case it wouldn’t really exist in a necessary way at all. (2017, p. 159)

Once again, Feser’s argument merely establishes that God is in no way potential, as regards His manner of existence. However, this conclusion tells us nothing whatsoever about His activities.

I conclude that Feser has failed to mount a satisfactory case for the existence of a purely actual Being, as opposed to an Ultimate Actualizer which needs nothing outside it to “hold it together” as a being, and which doesn’t need to be actualized by anything else, either in order to exist, or in order to ground the existence of other beings. That being the case, the arguments Feser puts forward in his Aristotelian proof for God’s unity, eternity, immutability, incorporeality, perfection, omnipotence, goodness and omniscience, all collapse, since they all proceed on the assumption that there is a purely actual Being, who is in no way potential. And since Feser’s other proofs all depend on the arguments put forward in his Aristotelian proof for these divine attributes, it follows that they too are unsound arguments, as they all rest on the same dubious premise that a purely actual Being exists.

===================================================================

RETURN TO MAIN MENU

5. Feser’s flawed argument that there can only be ONE First Actualizer

The Temple of Heaven in Beijing, built in honor of Shangdi, who was regarded as the absolute God of the universe in ancient China.

Feser’s argument for the unity of the First Actualizer is, as we will see, marred by two gaping holes in his logic: Feser fails to anticipate the possibility that two First Actualizers might not belong to any common natural category, and might therefore be characterized by two completely different sets of perfections, which they both realize in their entirety (making them both perfect, in their own respective ways); and he also ignores the possibility that even if they both belong to the same category, they may differ in characteristics which are neither perfections nor deficiencies, such as color.

Feser’s Aristotelian proof of the unity of the First Actualizer

Feser outlines his argument for the unity of a purely actual Being in his formal statement of the Aristotelian proof of God’s existence:

15. In order for there to be more than one purely actual actualizer, there would have to be some differentiating feature that one such actualizer has that the others lack.

16. But there could be such a differentiating feature only of a purely actual actualizer had some unactualized potential, which, being purely actual, it does not have.

17. So, there can be no such differentiating feature, and thus no way for there to be more than one purely actual actualizer. (2017, p. 36)

Feser sets up his argument for the unity of the First Actualizer by introducing the notion of a privation, and linking it to the related notion of a potential. To have a privation is to fail to realize some potential, and to be perfect is to be without any privations, or deficiencies:

For example, a squirrel which has been hit by a car may be unable to run away from predators as swiftly as it needs to; and a tree whose roots have been damaged may be unstable or unable to take in all the water and nutrients it needs in order to remain healthy. A defect of this sort is (to use some traditional philosophical jargon) a privation, the absence of some feature a thing would naturally require so as to be complete. It involves the failure to realize some potential inherent in a thing. Something is perfect, then, to the extent that it has actualized such potentials and is without privations. But then a purely actual cause of things, precisely since it is purely actual and thus devoid of unrealized potentiality or privation, possesses maximal perfection. (2017, p. 30)

Two points are worth making here. First, while having a privation entails having an unrealized potentiality, it does not follow that being perfect and having no privations entails having no unrealized potentialities. Thus a perfect being could still have potentialities which it does not realize. What a perfect being cannot have are potentialities which it should realize but is unable to.

Second, Feser’s definition of maximal perfection is extremely modest: it would imply that an entity which is capable of doing only one thing, which is does very well, is maximally perfect! In my previous post, I discussed Alvin Plantinga’s hypothetical example of McEar, who has the essential property of only having the power to scratch his ear, and who is incapable of doing anything else. On Feser’s definition, McEar would qualify as a maximally perfect being. So, too, would a hypothetical entity called McEye, which is capable only of seeing what’s in front of it. That should tell us that something is very wrong with Feser’s definition of maximal perfection.

Feser then appeals to the notions of a privation and of maximal perfection, in order to explain why there can only be one purely actual Cause of things:

Could there be more than one such cause? There could not, not even in principle. For there can be two or more of a kind only if there is something to differentiate them, something that one instance has that the others lack… More generally, two or more things of a kind are to be differentiated in terms of some perfection or privation that one has and the other lacks… But as we have seen, what is purely actual is completely devoid of any privation and is maximal in perfection. Hence, there can be no way in principle to differentiate one purely actual cause from another in terms of their respective perfections or privations. But then such a cause possesses the attribute of unity – that is to say, there cannot be, even in principle, more than one purely actual cause. hence it is one and the same unactualized actualizer to which all things owe their existence. (2017, p. 30)

Later, in chapter 6, Feser elaborates his point, by appealing to Aristotle’s account of how two things of a kind can be said to differ:

… God is purely actual, with no potentiality at all. And this entails his unity, because there cannot, even in principle, be more than one thing which is pure actuality. The reason is that for there to be more than one thing of a certain kind, there must be a distinction between the thing and the species of which it is a member, or (if the thing in question is a species) between the species and the genus of which it is a member. And there can be no such distinction without there also being a distinction between the thing’s potentialities and its actualities. (2017, p. 186)

Two gaping holes in Feser’s logic

European wild horse phenotypes. Image courtesy of DFoidl and Wikipedia.

We can now see the gaping holes in Feser’s argument for the unity of the Purely Actual Actualizer. First, Feser assumes, without justification, that if there were two purely actual beings, they would be two of a kind. That would make sense only if “being actual” defined some natural kind, like “being a horse.” However, there is no reason to think that it does. There may not be any common term (like horsiness) which can be predicated univocally of two purely actual beings; the resemblance between them may be purely analogical. Feser should be aware of this possibility: in his book, he carefully distinguishes between terms like “animal,” which are predicated of all species in exactly the same way (univocally), and terms like “being,” which are predicated analogically of different entities (2017, pp. 178-179). Why, then, couldn’t “First Actualizer” be an analogical term, rather than a univocal one?

Second, there is an illicit slide in Feser’s argument, from one meaning of lack to another. When Feser writes that there can be two or more of a kind only if there is “something that one instance has that the others lack,” the notion of “lack” he employs is: does not have. Two horses, for instance, may be completely alike in all respects except for their color: one is black, and the other is a chestnut. Blackness is something that the chestnut horse does not have. But it is not something that the chestnut horse should have, so we do not call this lack a defect. Next, Feser appeals to the stronger premise that “two or more things of a kind are to be differentiated in terms of some perfection or privation that one has and the other lacks.” Here, he is assuming that these things can only differ by virtue of some excellence which one possesses and which the other fails to realize. Finally, Feser argues that a purely actual being is free of all imperfections, in order to establish that it is unique.

In short: what Feser overlooks are: (i) the possibility that two purely actual beings might not share a list of common perfections which they are both supposed to possess, but might instead possess two completely different sets of perfections which they both realize in their entirety, making them both perfect in fundamentally different ways (think of McEar and McEye); and (ii) even supposing that two purely actual beings share such a list of perfections, there remains the possibility that they may differ in features which are neither perfections nor deficiencies, like the color of a horse.

I conclude that Feser’s argument for the unity of a purely actual Being is a badly flawed one, which trades on ambiguity and contains a number of unexamined premises.

Unfortunately, Feser’s faulty argument for the unity of a purely actual Being doesn’t just invalidate his first (Aristotelian) proof of God’s existence; it invalidates two of his other proofs, as well, as the following excerpts from the Augustinian and Rationalist proofs reveal:

(a) The Augustinian proof

19. A necessarily existing intellect would be purely actual.

20. There cannot be more than one thing that is purely actual.

21. So, there cannot be more than one necessarily existing intellect. (2017, p. 110)

(b) The Rationalist proof

19. A necessary being would have to be purely actual, absolutely simple or noncomposite, and something which just is subsistent existence itself.

20. But there can in principle be only one thing which is purely actual, absolutely simple or noncomposite, and something which just is subsistent existence itself. (2017, p. 163)

By relying too heavily on the Aristotelian argument as the backbone of his proofs of God’s existence, Feser has done himself a disservice, since any defect in any portion of the Aristotelian argument which is borrowed by the other proofs will render those arguments faulty, as well.

To sum up: Feser’s first, Aristotelian argument for God’s existence is flawed at its very roots. It fails to establish the existence of a purely actual Being, and it fails to prove that there is only one such Being. Since Feser’s arguments for the remaining Divine attributes are built on the foundation of these two attributes, I conclude that the Aristotelian argument is utterly useless, as a proof of God’s existence.

===================================================================

C. FLAWS WHICH UNDERCUT FESER’S SECOND PROOF

Summary of my argument: I now turn to Feser’s second, neo-Platonic argument for God’s existence, which endeavors to establish the existence of one (and only one) absolutely simple Being, which is utterly devoid of parts. Unfortunately, nowhere in his entire book does Feser provide a definition of “part”: a startling omission. After examining various passages in Feser’s writings, I put forward a definition which I believe captures Feser’s metaphysical insights as to what what a part is, judging from scattered passages in his writings. Unfortunately for Feser’s argument, the definition I provide shows only that an absolutely simple Being cannot be composed of any elements which are ontologically prior to it. Nothing in the “Feserian” definition which I propose precludes such a Being from having either properties (which flow from its essence and are ontologically posterior to it), or intrinsic accidents (such as a horse’s color, which does not flow from its essence, but which it has to have anyway). Feser, however, upholds a very radical view of Divine simplicity: not only does he hold God’s nature to be simple (as most Christians do), but as a Thomist, he also holds that God has no properties or real accidents of any kind. Additionally, Feser’s argument that there can only be one absolutely simple Being suffers from the same deficiencies as his Aristotelian argument that there can only be one purely actual Being. Feser assumes, without justification, that if there were two absolutely simple beings, they would both be members of some common category (i.e. a species or a genus); and he also assumes (without explaining why) that the additional features which distinguish any two members of this common category would have to be parts of those entities. I conclude that these holes in Feser’s logic, coupled with his failure to provide a proper definition of “part,” vitiate his second, neo-Platonic argument for God’s existence.

RETURN TO MAIN MENU

6. Bad Mereology: Feser’s failure to define what it means for something to be a part of a whole

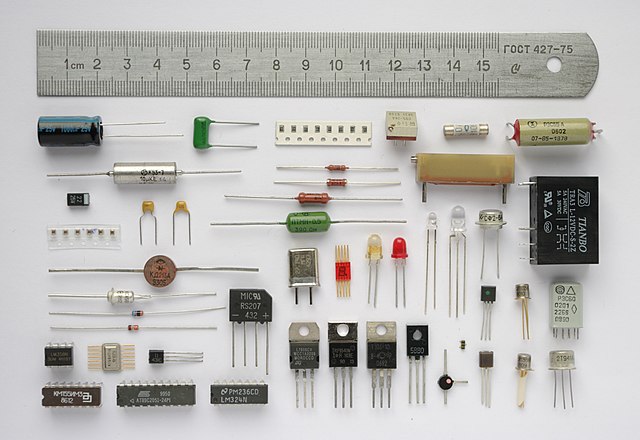

Various electronic components. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Feser writes quite a lot on the subject of whether God has parts. Curiously, however, nowhere in his entire book, or in any of his other books on metaphysics, does Feser tell us what he actually means by one – a startling omission. The question is important, because the term “part” is variously defined by different authors.